Narratology

Tzvetan Todorov wanted to analyse the structural properties of narratives and develop a general theory that could be applied to all stories. He called this new approach narratology, or science of the narrative.1

He described how stories should begin with a stable situation, but this routine is disturbed by some force which results in a state of imbalance. Characters then have to search for a new equilibrium. This three-part structure is summarised in the following diagram.

Todorov used a story from Boccaccio’s “The Decameron” to illustrate this three-part structure. We are going to use contemporary examples explore the fundamental structure of narrative.

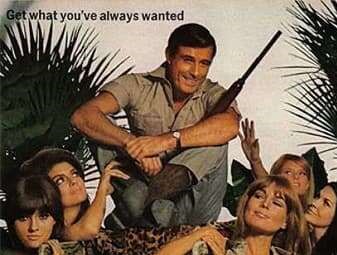

Using Todorov’s framework, the visual composition of Score might depict a new equilibrium when order is restored and ambitions are fulfilled. The hero…. [can you add a few phrases to unpack this thought]

Can you apply Todorov’s theory to video clips Old Town Road or Ghost Town?

LEVI STRAUSS: BINARY OPPOSITIONS AND MYTHEME

Binary Opposition

We use Binary Opposites in our everyday life to help us make sense of events and stories

Binary opposites are used in films to help plots, they are also used in music videos as part of a narrative to reinforce song lyrics.

Levi- Strauss believed that the way we understand words depends not on the meanings attributed, but by our understanding of the word in relation to

it’s ‘opposite’.

e.g.

MEN = STRONG

therefore

WOMEN = WEAK

Binary opposites become ingrained in society through repetition. These then become “invisible” and form part of our dominant ideologies. We then may act on them as a culture.

For example, as we have been taught to associate the word “black” with “bad”, “evil” or “dirt”, individuals can develop prejudices based on binary

opposites

Is the concept of binary opposition useful in reading our CPS in advertising and musical video-clips?

Find examples from Score, Sephora, Ghost Town, Old Town Road

Mytheme

What does the analysis of culturally important myths reveal about our values and ideology?

Definition

Mythemes are units of narrative features we can use to compare different myths from around the world. The concept was devised in the 1950s by Claude Lévi-Strauss who wanted a more scientific approach to analysing tribal stories and folklore. By breaking down myths into their characters, actions and themes, Strauss hoped he could quantify culturally important meanings and celebrate our rich diversity of thinking.Contents

Why Study Myths?

Lévi-Strauss believed anthropologists were too quick to dismiss myths as “idle play” or a “coarse kind of speculation” because he recognised the stories expressed “fundamental feelings common to the whole of mankind”, offered some sort of “explanations for phenomena” science had yet to explain, and reflected complex “social structure and social relations”.

He was also fascinated by the “astounding similarity between myths collected in widely different regions”. Could closer scrutiny of myths help develop our understanding of the world and reveal something about mankind?

Lévi-Strauss needed a way to compare and contrast myths. He needed a method.

Mytheme and Semiotics

After splitting signs into two parts, the signifier and signified, Ferdinand de Saussure established the principle of an arbitrary relationship between signs and their meaning. For instance, there is no reason whatsoever the combination of sounds which form the word “water” should refer to its equivalent in the real world. Lévi-Strauss applied a similar approach to analysing myths.

A mytheme consists of the narrative feature and what it signifies.

However, in the same way the Latin “aqua” was perfectly fine for centuries, Lévi-Strauss also realised myths and their individual units were influenced by the culture that produced the story. The physical form of the mytheme might change, but its “properties” will remain.

He also argued we can update and translate myths, but their meanings will be “preserved” because mythemes contain “properties… above the ordinary linguistic level”. That process sounds a lot like Roland Barthes’ second order of signification – myth. But please do not confuse the two terms.

Character, Action and Theme

In order to collect useful data, Lévi-Strauss had to devise his own way of breaking down myths into units of meaning he could use to compare and contrast the narratives. He identified character, action and theme to be their smallest elements.

Lévi-Strauss illustrated this approach by comparing the Greek myths of Cadmus slaying the dragon and Oedipus killing the Sphinx. Both of these monsters are trying to destroy mankind. Although some of the specific details in the stories are different, the signification remains the same – men overcoming the supernatural to save society.

If you are already familiar with Vladimir Propp’s character types and spheres of action, you will appreciate Lévi-Strauss’ method here. You can also see this approach in the way Roland Barthes divided stories into lexias so he could classify the narrative codes.

Once you have identified the various mythemes, you can start arranging them into semantic packets and try to uncover some of the underlying meanings in the myths.

Mythemes and the Media

Although Lévi-Strauss was investigating classical myths and tribal stories, we can use his ideas to find out more about our own culture and society because media texts often reveal our dominant values and beliefs. Since the media has an agenda-setting function and helps to normalise views and attitudes, the study of its output is essential in the fight against inequality and injustice, especially when important ideas are misrepresented and minority groups are reduced to inappropriate stereotypes.

Mythemes and Superheroes

Here is a quick and obvious example of using mythemes to interpret contemporary texts. Batman, Superman and Shazam are different superheroes who use their powers and skills to protect mankind from various forces of evil. Think about their origin stories. Batman’s parents are killed outside the theatre, Superman’s parents remain on Krypton, and Shazam loses his parents to a mysterious accident when they are an archaeological dig.

Each of these narrative actions could be considered a mytheme. What do these semantic echoes reveal about our culture and our understanding of the world?

By the way, Lévi-Strauss identified bloodlines as an important feature in the Cadmus and Oedipus stories.

Vladimir Propp

An introduction to Propp’s 7 character types and spheres of action in the narrative functions.

Character Types

Vladimir Propp (1928) claimed characters could be defined by their “spheres of action” and the role they played in the progression of the story. After studying 100 fairy tales in tremendous detail, he identified seven archetypes: the villain, the donor, the helper, the princess, the dispatcher, the hero, and the false hero.

These seven types provide an effective framework for analysing and understanding the functions the characters play in the narrative. Let’s take a look at each role.Contents

Villain

At the start of the story, the villain causes some “form of misfortune, damage or harm” by stealing a magical object for their own gain, ruining crops, kidnapping a person, or committing a murder. They could be a dragon, a witch, a stepmother or even the devil himself. These characters often use a disguise to perform their wicked deeds, such as the dragon who turns into a golden goat or the witch pretending to be a “sweet old lady”.

Their evil action will, of course, lead to a fight or another form of struggle with the hero.

Villains in contemporary media include Ganon from the Legend of Zelda series, Thanos from Marvel’s Endgame (2019), and the iconic Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz (1939).

The Donor (provider)

For most of the folk tales in Propp’s study, the hero needs some sort of agent to defeat the villain and complete their quest. This object is provided by the donor. For example, a robber shows the hero a weapon, merchants display incredible wares or an old man can provide a magical sword.

The donor offers the hero these things if they can fulfil a task or test, such as the witch who gives the girl chores around the house or the hero who has to serve the knights of the forest for three years. During the encounter in the forest, on the road or some other wilderness, the donor might also make a request for mercy or a favour. Once the hero has satisfied the donor’s demands, they will be rewarded with agent they need to restore order in their world.

Lucius Fox, played by Morgan Freeman in Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy, provides lots of technology to help the hero destroy the Joker’s evil plan to bring chaos to Gotham. Tamatoa, the giant coconut crab who has Maui’s magical fishhook in Moana (2016), is another example of a donor.

The Helper

A helper uses their force or cunning to help the hero acquire the object needed to remove the misfortune from their lives. Perhaps they help break a spell or resuscitate a victim. They might help the hero choose the right route or carry them to their destination. In some of the folk tales, the helper rescued the hero from a dangerous pursuit.

At the end of the story, they might also offer the hero new garments which will represent the protagonist’s transformation.

The sidekick in most films could be considered helpers. Morpheus and Trinity unplug Neo and help him rebel against the machines in The Matrix (1999), Palico assists the players in their quest throughout the Monster Hunter video game franchise, and Donkey is always there to support Shrek.

This role is very similar to Ronald Tobias’s buddy concept and his example of the Scarecrow, Tin Woodman and Cowardly Lion from The Wizard of Oz (1939).

The Princess (a sought-for person)

In many of the folk tales, the hero sets off on a quest to rescue a princess. Perhaps the princess is a victim, such as the character who is tormented by the devil every night and the hero must save her. During the story, she might give the hero a token, such as a ring or cloth, before he fights the villain. Of course, the hero’s journey concludes when he marries the princess.

However, in some stories the hero has to search for a missing person, most likely his sister. Therefore, the sphere of action that defines the princess has nothing to do with the royal title. The archetype refers to the “sought-for” character who the hero has to find to complete his quest.

It is important to note that there are a number of royal princesses in the stories who have a different sphere of action. For example, there is the princess who orders her servants to take her husband away into the forest and kill him, a princess who chops the leg off one of her victims, or the princess who steals a magic shirt and kills her husband. These functions indicate the princesses are actually the villains in those folk tales.

Remember, Propp was referring to the roles the characters played in the functions of the stories rather than their names or background.

The Sultan’s daughter in the platform game Prince of Persia (1989) needs rescued, and Bryan Mills, the former CIA operative played by Liam Neeson, has the set of skills needed to track down his teenage daughter who has been kidnapped in Taken (2008).

Modern damsels in distress are usually more empowered than their traditional counterparts. For example, Superman is always saving Lois Lane from certain death but she is certainly not a passive character. Although Ray Gaines has to rescue his daughter in the disaster film San Andreas (2015), she proves to be very capable in surviving the earthquake and tsunami until he arrives just as the building collapses.

Dispatcher

After the villain has committed a terrible deed and brought misfortune to the land, the dispatcher calls for help. In many of the stories, the tsar promises a reward to the hero who can solve the problem, or a family member requests their children end the evil blighting their home. In one example, a mother informs her son about his sister’s abduction. He then sets out on a quest to rescue her from the evil dragon.

Perhaps the hero was punished at the start of the story and the dispatcher releases them so they can go on a quest to save the day. Propp offers the example of a girl wrongly condemned to death for murder. A cook sets a her free and slays an animal instead to present its heart as proof of girl’s execution. In this tale, the cook is the dispatcher.

In the original Star Wars trilogy, the android, R2D2, dispatches Luke Skywalker on his quest to find the Jedi Knight, Ben Kenobi. In Alien (1979), the computer on the spaceship Nostromo, known as Mother, alerts the crew that a distress signal has been received and needs to be investigated. In Attack On Titan, Armin Arlert describes the world outside the walls which inspires the protagonist, Eren Yeager, to see the world beyond those confines.

The Hero

Propp defined two types of hero. First, there is the seeker who “agrees to liquidate the misfortune” suffered by another character and goes on a quest to defeat the evil. For example, if they have to rescue a young girl who is kidnapped by a wicked villain.

The second type of hero is the victim who “directly suffers from the action of the villain” at the start of the story. Perhaps they were warned not to “look into this closet”, “venture forth from the courtyard” or “pick the apples”, but the villain persuades them to violate the “interdiction” and they are punished for their disobedience. The victimised hero will then have to find a magical agent to help them resolve the misfortune.

Media texts are full of heroes. Katniss Everdeen competes in The Hunger Games franchise and then leads a rebellion against the oppressive Capitol, T’Challa, played by Chadwick Boseman in Marvel’s Black Panther (2018), has to defend Wakanda, and Mario from Nintendo’s most popular franchise has to save Princess Peach from the villainous Bowser.

The False Hero

When the hero finishes their quest and the evil is defeated, the false hero takes credit for the victory. For example, the hero’s brothers pretend they captured the prize or the general tells the tsar he conquered the dragon. These characters appear to be good but it quickly becomes obvious they are corrupt.

A great example of the false hero is Hans from Disney’s Frozen (2013) who pretends to love Anna but is plotting to steal the throne of Arendelle. Draco Malfoy from the Harry Potter series is another character who presents himself as the hero but is often thwarted by the protagonist and his friends. Finally, Marlene in the video game The Last of Us seems to help Ellie but then wants to use her in an experiment that could lead to her death.

Conclusion

Although he was investigating Russian fairy tales, Propp believed his character types were universal across different cultures and time periods. This attempt to classify the “constant elements” of narrative is now considered a structuralist approach to understanding storytelling. You should look at Roland Barthes’ five narrative codes and the concept of mytheme because both frameworks are also trying to uncover the fundamental elements of narrative.

Studying the recurring patterns in storytelling can offer interesting insights into aspects of our culture, especially our values and attitudes. For example, the binary opposition of the villain and hero could be linked to the importance of morality in society. Perhaps the conclusions of the fairy tales points towards our desire to have order in the world.

The seven character types are also incredibly useful if you are going to create your own compelling stories or media texts. If you want to develop your understanding of how these spheres of action fit into the plot, you should read our introduction to Propp’s narrative functions next.