POST-FEMINISM

The meaning of this term is subject to debate and has been interpreted in multiple and occasionally competing/antagonistic/debatable ways.

It mostly referred to a 1990s a reaction to the second wave of feminism (1970s and 1980s) and proposes a much more positive reading of the changing ways that women are represented in media — from the 1990s till today.

Post feminist reads more positively the representation women of popular culture, especially in TV series like Sex and the City, movies (the Diary of Bridge Jones), chic-literature (genre of women-oriented fiction) and music bands like Spice Girls that exhibit what has been described as Girl power. Women who now prevail in popular imagery can be both spectacular and free: they balance forms of femininity associated with beauty products, fashion and elegance and at the same time, appear independent, strong-willed and liberated.

They express freely their desire to be seen — but also to be themselves the lookers, the doers, action-heroines with agency. Women seem to achieve professional success and assume control over their image and personality, even if they prescribe to traditional ideals of beauty and self-promotion.

Critics has pointed that in post feminist context, the politics of liberation has been replaced by consumerism. Popular culture heralded a false achievement of equality based on individualism. This has also been linked with the ideology of neoliberal era. In a market-oriented organization of society career, personal gain and private enterprise is more important that social equality.

A part of the post-feminist condition, is the so called do-me feminism Raunch culture. Advocated by feminists like Camilla Paglia, this type of reading sees ‘sexual freedom as key to female emancipation. As opposed to 1970s feminists, this strand of feminism does not see sexualization as degradation. Do-me feminists argue that women can use erotic forms of self-representation in art and media as forms of self-empowerment, creativity and freedom. Popular icons like Madonna but also models, artists, even porn-stars assume confidently control over their image and act consciously and playfully as objects and subjects of desire.

Another form of reaction to 1970s forms of critique to the ‘male gaze’ and the objectification of women’s bodies, was the focus on the female gaze: how do women see men and how women identify with other women in the media sphere.

according to Oxford dictionary: female gaze The ways in which women and girls look at other females, at males, and at things in the world. This concerns the kinds of looking involved, and how these may be related to identification, objectification, subjectivity, and the performance and construction of gender.

Female gaze also refers to ways of constructing media products that emphasize female perspective and point of views. How is the model, heroine, interviewee ‘sees’ the world and how are they positioned to be viewed by their readers/spectators?

How are men depicted in magazines/video clips/adverts for the eyes of women?

How useful is the concept of post-feminism or do-me feminism/raunch culture for reading magazines?

Use examples from Gentlewoman to support your answer.

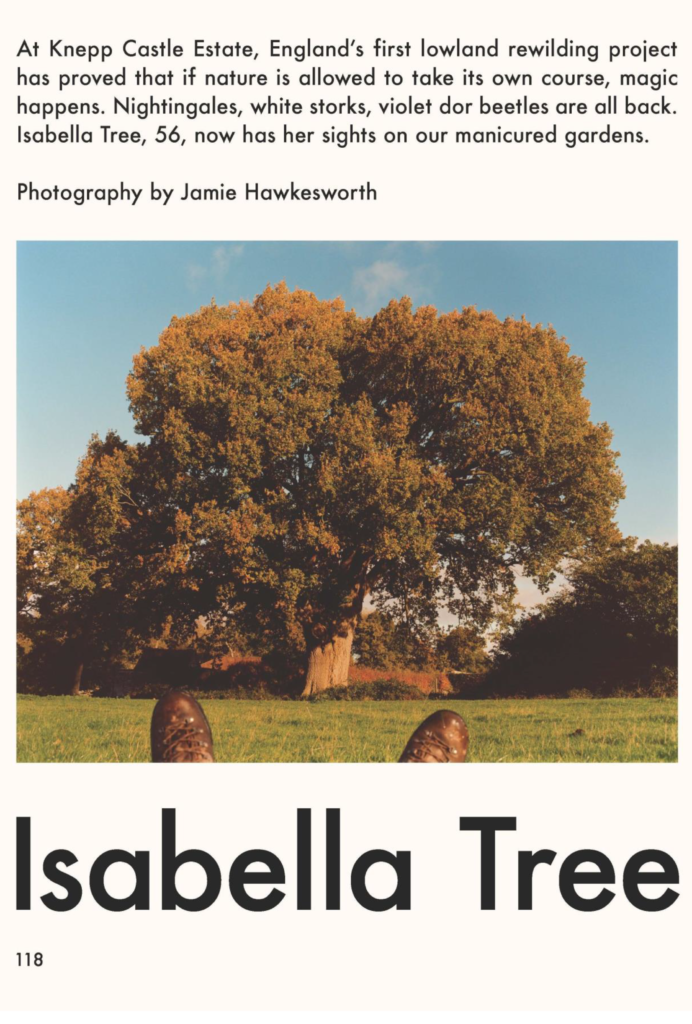

Can you discuss in the female gaze in response to the example below from Gentlewoman? (if you want you can make some research on Isabelle tree — and have a look at all the other images used in the piece that is dedicated to her)

Can you refer to another example where female can be discussed both in terms of the way a woman is looking at the world and the ways, she is looked at?

How useful is post-feminism and/or raunch culture in understanding the ‘Black Beauty is Beauty’ that advertises Sephora

Men and Post-feminism

Post feminism has also changed the way thinkers read men and masculinities. Historical changes like economic crises and changing industrial environments meant that women became more visible and increasingly took leading positions in professional environments, whereas many men lost their traditional credentials of empowerment. This led to crisis in masculinity: men do not always appear confident and capable of adapting in the demands of changing societies.

Since the 1980s, the emergence of service economy was coupled with the growth of lifestyle magazine and male beauty products. This created new ideals and types of manhood available to those how could afford to respond to these new consumerist standards.

Stephanie Genz and Benjamin A Brabon in ‘Men and Postfeminism’ argue that

‘The increasing commercialization of masculinity (during the 1950s 1960s, 1970s) culminated in the male of male gaze of the 1980s. Whereas previously the female body had been the exclusive site of voyeuristic and sexualised representation by the media, the 1980s witnessed ‘the commercial exploitation of men-as-sex-object’ (Beynon 2002:103). This version of commercial masculinity transformed the male body into an objectified commodity that saw the rise of retail clothing outlets for men, new visual representations of masculinity on television and in the media and the growth of men’s lifestyle magazines.

This commercial masculinity that was based on look demanded wealth. Many economically disadvantaged men could not adjust to these new standards.

In this post-feminist context that persists till today, the male body (particularly the young ‘good-looking’ male body) is presented as a site of opportunity and power, not because of physical strength and manual labour, but a signifier of commercial over-activity.

The post-feminist moment witnessed the proliferation of new types of masculinity, distinct from the past, often in dialogue with new ideas about gender equality and commercial form of status and visibility.

For example

the ‘New Man’

The new man as been described conflictingly as pro-feminist, narcissistic, anti-sexist and sexually ambivalent. He is often seen within the context of a response to feminism, as a ‘potent symbol for men and women searching for new images and visions of masculinity in the wake of feminism and the men’s movement. The new man is in tune with feminism but is also described as hedonistic, narcissistic and consumerist.

This type of manhood has been criticized for being an advertising product, driven by commercial greed. It has also been criticized for being Western, white, middle-class and elitist. — a distant representation of masculinity, decidedly ‘other’ from the day-to-day lives of the majority of men.

Metrosexual

Sitting in between the New Man and the New Lad (new confident types of macho men), the metrosexual represents an excessive display of stylized heterosexual masculinity. More groomed than the New Man and not as sexist or ironic as the new lad, the metrosexual is less certain of his identity and much more interested in his image.

the term ‘metrosexual’ was coined in 1994 by Mark Simpson to describe ‘a young man with money to spend, living in or within easy reach of the metropolis… He migh be officially gay, straight or bisexual, but this is utterly immaterial because he has clearly taken himself as his own love object and pleasure as his sexual preference.’ Epitomised by David Beckham, the ‘metrosexual’ extends the narcissistic and self-absorbed characteristics of the new man, revelling in the consumerist heaven that is the moder-day metropolis.

Robert Bly’s article ‘Iron John’ propagated the re-emergence of strong, macho, physically dynamic modes of manhood. These were exemplified in muscular cinematic icons of action-heroes in the 1980s like Rambo. This evolved into the creation of the model of the ‘new lad’

The ‘New lad’ was the product of 1990s and was a reaction to the new man and the metrosexual. Arriving in 1994 with the launch of Loaded magazine, the new lad embraced laddish behaviour — reveling in naked images of girls, games, footie and booze. Whereas the new as pro-feminist, the new man is pre-feminist (critical, dismissive of feminism), displays retro-sexism and seems to embrace a nostalgic revival of old ways of being man but within new consumerist contexts. While recalling old versions of manhood, the new lad is eager to throw of the constrains of traditional roles, like the husband or the father. His ideal lifestyle is not defined by marriage but by fun, consumption and sexual freedom, unfettered by traditional male responsibilities. In this sense, the new lad’s appeal was broader than that of the new man as it spoke directly to the working class masculinities that were excluded by the upmarket profile and commercial status of high-income earners.

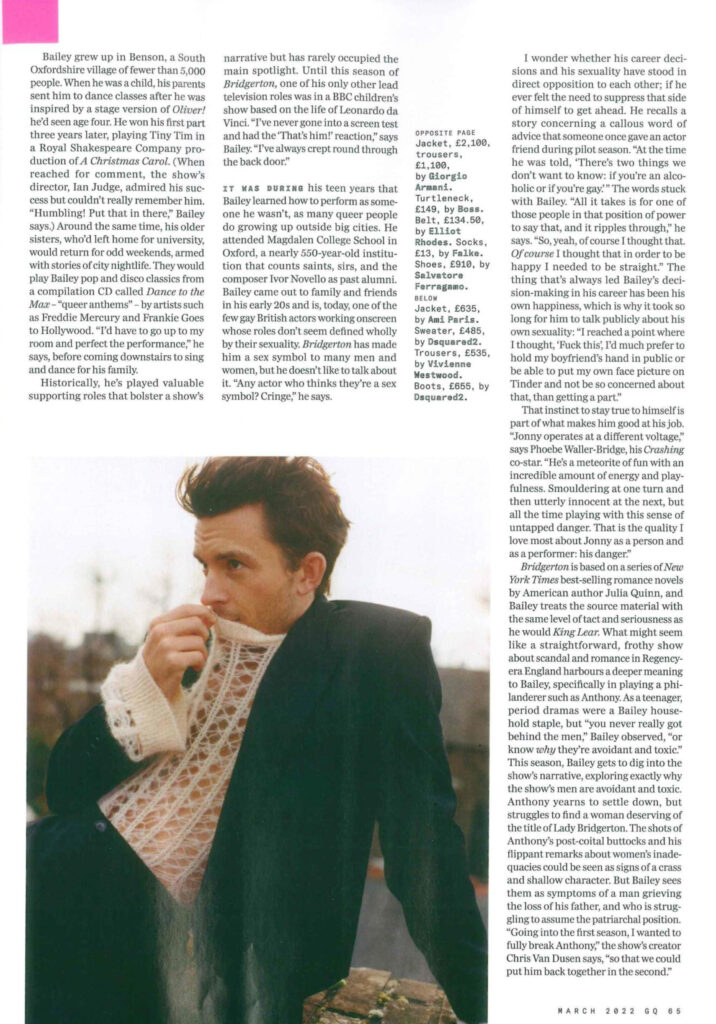

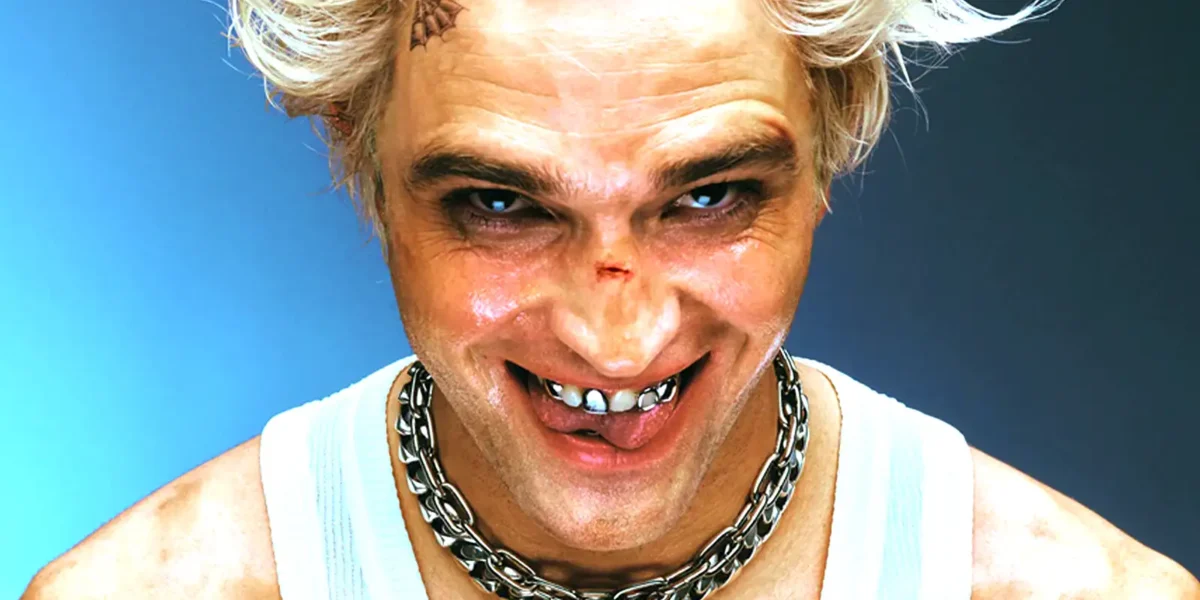

How does the discussion of new types of masculinity help us understand the media products below? Do the men below adapt and/or challenge commercial forms masculinity?

Can you discuss the context of these products too?