Theories of Gender Performativity:

Key Vocabulary

- Sex and gender: Sex is a biological form of classification that is assigned at birth

- Gender is a social construction, a ‘learned’ way of interpreting one’s body that is subject to change.

performativity refers to ‘a stylised repetition of acts’ — a process of becoming, an intervention into social reality

Butler argues that gender is not a natural ‘fact’ but a way of acting out our personhood. We are expected to reproduce certain ways of inhabiting and presenting our bodies and our personalities to others

- Gender as historical situation rather than natural fact: The ways that we perform our gender roles change over time and space. What is meant to be a ‘woman’ is different in a Victorian society of the 19th century, a classical or a post-industrial one.

- Subversion: Subversion is the act of disrupting the expected/established/hegemonic ways of being or acting out a gender. Drag acts highlight that to be man or a woman can be a form of spectacle, a way of directing and presenting one’s body, behaviour and interaction with others

Exam Question:

According to Judith Butleer gender is not what you ‘are’ but what you do. Gender is a form of performativity.

To what extend do magazines promote established or disruptive ways of interpreting one’s gender?

According to Judith Butller, gender is not a fixed physical condition, but a social construction. People learn how to act out their genders according to established ideals of appearance and style. Men and women learn how to reproduce certain ways of moving, speaking, posing, dressing up and interacting with others. Media and more specifically, magazines like GQ and the Gentlewoman quite often reinforce stereotypical ways of performing gender. However, at the same, they provide space for alternative forms self-presentation which challenge binary understandings of identity.

The Gentlewoman features on its cover a super feminized image of Scarlet Johansson. Her sensual gaze, red lipstick and suggestive smile could be interpreted as a normalized/established way of performing womanhood. She looks erotic, mysterious, smooth and inviting. However, these elements of her posturing only partially conform to traditional prescriptions of what a woman should look like. This ‘look’ also points to unconventional styles of socialization and role-playing. The vibrant, colorful and bold tones of her make up point to hip/rebellious/adventurous/subcultural ideals of beauty and personhood which to some extent challenge traditional gender stereotypes of ‘reserve’ and ‘humility.’ Her facial expression appears self-confident and active. This woman wants ‘to look at’ as much as ‘to be looked at’ and in this way, she represents a non-traditional interpretation of her gender identity.

In the inner pages of that magazine, the interview with…

Task 2: In what ways Judith Bulter’s ideas on the performativity of gender can help us read the CPS video clip old town road?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r7qovpFAGrQ

The Performativity of Gender

Gender Performance, Gender Trouble & Queer Theory

source:https://www.perlego.com/knowledge/study-guides/what-is-judith-butlers-theory-of-gender-performativity/

The theory of gender performativity was introduced by feminist philosopher Judith Butler in her 1990 text Gender Trouble. For Butler, and for queer theory more broadly, gender is what you do, not who you are. Rather than viewing gender as something natural or internal, Butler roots gender in outward signs and actions. These performative acts do not express an “innate” gender but actually create gender itself; the performance of gender produces the identity it claims to reveal.

Gender is performed not through a singular act but through ritualized repetition. This repetition gives gender its illusion of stability; the repeated performance of gender in accordance with social norms (men ought to speak like this, women ought to dress like this) reproduces and reinscribes those norms, making them seem legitimate and fixed.

We are compelled to repeatedly perform gender in certain ways because societal structures reward those who perform gender “correctly” (according to a strict binary) and punish those who do not. Think of Disney’s The Little Mermaid (1989): Ariel and Erik conform to normative gender expectations, and they are rewarded with a happy ending; on the other hand, Ursula—with her deep voice, short hair, plus-sized body, and makeup inspired by the drag queen Divine—is villainized and defeated.

Performing gender “correctly” gives us a designated role in society and allows us to be recognized as a full, “real” subject. Our conscious and unconscious awareness of gender constraints means we are always performing gender to an audience, even an imagined one.

Gender’s performativity thus produces gender while concealing its own creation. As Butler writes in Gender Trouble,

Judith Butler and Performativity

To what extent is gender determined by society and our performance of those roles? Find out more in our introduction to gender trouble.

What are Gender Roles?

In what is considered to be their most important publication, “Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity”, Judith Butler criticised the “restricted meaning of gender to received notions of masculinity and femininity”. Gender goes beyond those traditional binary definitions.

They also argued gender stereotypes are “compelling social fictions” rather than some sort of natural fact. This “stylized repetition of acts” follows socially established rules and the performances are repeated so often, they “produce the appearance of substance” or the “illusion” they are “stable”.

The various acts of gender create the idea of gender.Judith Butler

Since gender is performed, the “bodily gestures, movements and styles” that are used to signify gender identities will be determined by the ideology and customs of that particular society. In other words, definitions of gender can change depending on the historical and cultural context. Judith Butler called this process performativity.

Gender and Socialisation

Many theorists believe we are not born with a gender. We learn the roles through the imitation and repetition of behaviour we see, for example, on television and in our social media feeds. The symbolic modelling aspect of Albert Bandura’s social learning theory supports this idea of young people copying what they see on television. You might be interested in our summary of David Gauntlett’s views on gender which has a section on this fluidity of identity. He suggested gender representations are not fixed and do change over time.

Butler compared gender to a social drama. In their analogy, men and women are the protagonists in the narrative and we are all expected to perform our roles. We learn and interpret our lines through a process known as socialisation. In media studies, we also use the term enculturation.

Of course, if you change the script, the new story is “recirculated” through society and the gender identity is revised. For instance, if lots of young boys started wearing dresses tomorrow, our view of what is normal will begin to change. In fact, the terms “gender-neutral” and “non-binary” are being used by more and more fashion outlets to describe some of their clothes.

Butler concluded gender is not a stable signifier but is “open to intervention and resignification”. Put simply, gender is a social construct, or performative.

Interestingly, they argued gender is not something we can internalise because it will always remain a performance.

Like a Girl

The idea that boys are more athletic and competitive than girls is a sexist perspective that has been promoted by the media for generations. You might be familiar with the phrase “like a girl” which is used on the playground to insult a boy’s strength or sporting skill. But it also denigrates women because it suggests they are weak and ineffectual. This can have an incredibly damaging impact on a young girl’s identity and confidence.

The following promotional video fights against that negative stereotype.

This advertising campaign is a fantastic attempt to intervene and change the gender roles that limit our identity and potential. If the script really is to change so that “run like a girl” means “run as fast as you can”, the media has to support the message by broadcasting more elite women’s sports and celebrating their achievements.

Applying Gender Performativity to GQ

Gender and Performativity

Fashion and beauty were traditionally encoded in the media as feminine, so advertisers had to find ways to make male audiences interested in grooming products. For example, in 1967, the agency behind the Score Hair Cream appealed to the male gaze – buy the product to conquer the glamorous girls. There is a clear binary opposition between the rugged and adventurous man compared to the passive women who hoist him up on the litter.

Judith Butler (1990) described gender as “stylized repetition of acts”. The representation of masculinity and femininity in the Score advertisement is another performance which strengthens the dominant ideology. With its global reach, GQ plays a significant part in this performativity.

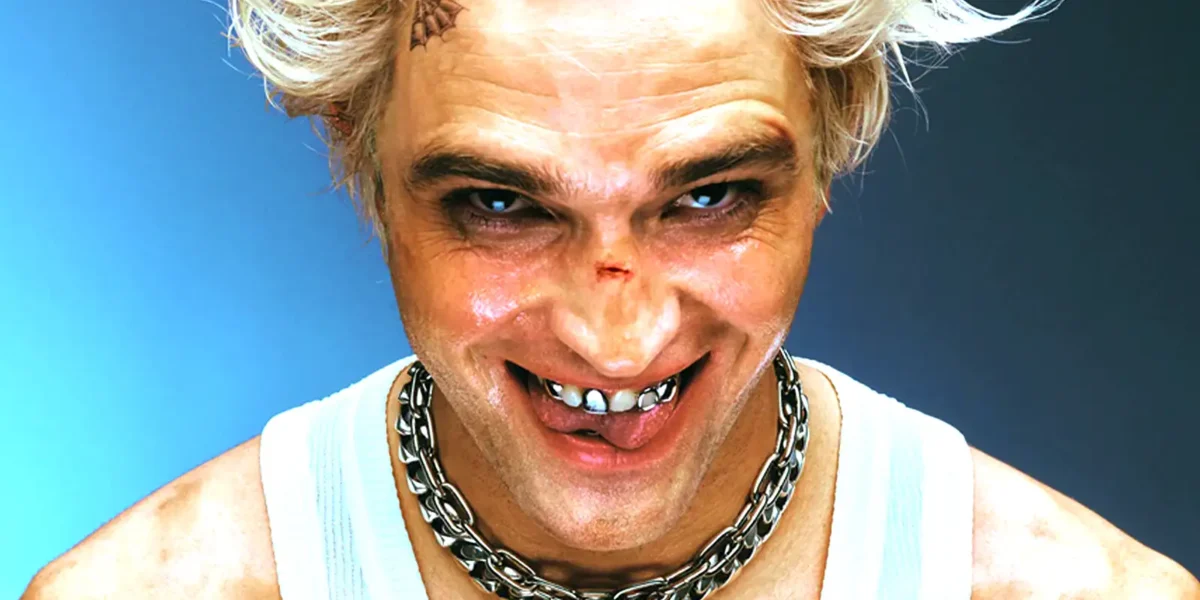

Although Edward Pattinson seems unconcerned with his rough appearance on the cover, he is raising questions about common beauty standards and his role as a teenage heartthrob. Jonathan Bailey might be a charming womaniser in Bridgerton, but the actor is content to discuss his homosexuality, saying, “I’d much prefer to hold my boyfriend’s hand in public or be able to put my own face picture on Tinder and not be so concerned about that, than get a part.” The interviewer concludes Bailey is a “sex symbol to many men and women”.

Rather than sparking any gender trouble, the representation of Bailey offers a broader vision of masculinity beyond the old heteronormative values. GQ wants to position itself as part of this evolution of masculinity. You should read Wikipedia’s entry on metrosexuality for more information on the representation of masculinity in GQ magazine and other media texts.

Applying gender performativity in the Gentle Woman

Modern Punches and Representation

The first article we need to consider is the interview with Ramla Ali whose “lightning speed and exceptional footwork” in the boxing ring elevated her to “global athlete status”. She refused to “give in to the pain” and “worked harder” to represent Somalia at the 2020 Olympic Games and then compete as a professional in the sport. The Gentlewoman “showcases inspirational women” and Ramla is an incredible role model.

Liesbet van Zoonen (1996) suggested “competition, individualism, ruthlessness” were supposed to be masculine values, but Ramla’s physical and mental strength challenges that traditional ideology. The image of her standing tall and flexing her muscles in victory conveys her self-determination and power effectively to the audience. We might even argue the blue tracksuit plays with the colour codes of masculinity.

Ramla describes herself as “a total tomboy” who would “pick trainers over make-up any day”. She actually lied to her mother about boxing, telling her “I was just going to the gym for a swim or spin class” because that was more socially acceptable for a girl.

The tomboy stereotype is seen by some critics as a threat to society because it undermines the binary opposition between men and women. However, the tone of the article suggests Ramla is proud of this identity because of her strong sense of independence. Judith Butler (1990) argued gender is a social construct that is constantly being reinforced through our behaviour and interactions with others. Gender is performative in the sense that it is maintained through this “stylized repetition of acts”. Ramla is fully aware she is resisting the dominant ideology and she is eager to write her own script: “I just want to be perfect – is that too much to ask?”

The imbalance of power between men and women is still evident in the world of boxing. Although “everyone is equal” in the gym, Ramla mentions how she had to “grab every opportunity” because they were “few and far between” in female sport and “the pay gap between men and women” remains “so huge”. That is why she has to rely on sponsorships from the likes of Nike and Cartier whose products she is modelling on page 67.

Ramla also refers to the negative stereotype of the thuggish boxer, preferring to tell people she is an “athlete rather than a boxer just to be spared the judgement”. There is no doubt this inspirational woman will continue to shift expectations.

Finally, in terms of genre, the interview is a straightforward question and answer session, so Ramla’s voice is unmediated through a narrator. It’s her own words. This is an important choice for a magazine which aims to deliver “warm and personal… conversations with fascinating women of the moment”.

Group Discussion

- Stereotypes are used to describe groups of people or places. However, these generalisations can be very harmful because then tend to exaggerate or oversimplify certain characteristics. When someone uses the phrase “like a girl”, what are they trying to say?

- What does the phrase suggest about gender and equality?

- How would you feel if someone made fun of your efforts and abilities?

- Can you think of any other phrases or terms that are cruel and hurtful? Try to explain the meanings behind the representations and why they might be inappropriate.

- Has the campaign made you re-evaluate some of the stereotypes you use to describe people and places?

Performativity and Bluey

Supported by BBC Studios in the UK, “Bluey” is an Australian cartoon targeted at young children. The story follows the wonderful adventures of Bluey – a puppy with an inexhaustible imagination. Like a lot of television shows, the narrative focuses on a nuclear family and their relationships.

In the first episode, Bluey’s dad freezes her in space and time with a magic xylophone and it is up to Bingo, her four-year-old sister, to save the day. In the second episode, doctor Bluey has to operate on her dad to rescue a cat from his tummy. With such heart-warming stories, it is no surprise “Bluey” is a commercial hit with children around the world.

However, many parents are surprised to learn that Bluey is a girl. Maybe we make assumptions about her gender because blue traditionally signifies masculinity. The programme also avoids gender stereotypes. For instance, Bluey does not really play with princess dolls and, instead, invents her own games that would appeal to both girls and boys. Perhaps there is an expectation that a sitcom with two children should feature a son and a daughter in the narrative.

In most media texts, colour codes are used to define gender, but young people are watching “Bluey” and not decoding the “blue is for boys” convention. If more programmes, games and films depicted a broader range of representations, it would be possible to break free from the old gender stereotypes.

Debates

Butler (1999) also reviewed some of the contemporary feminist ideas regarding gender constructs. They questioned the assumption that “the term woman denotes a common identity” and drew attention to the fact traditional feminism has ignored the tremendous diversity of women around the world. This perspective is shared by bell hooks who, for example, wanted to see a “broader, more complex vision of womanhood” in Hollywood films beyond the narrow representations traditionally depicted on the big screen.

Definitions of gender were not always compatible with Butler’s own experiences in the lesbian and gay community in America. They dismissed the idea that “the feminine belonged to women and believed gender was a “free-floating artifice”. The “splittings, self-parody, self-criticism” and “hyperbolic exhibitions” of gender drew attention to their “fundamentally phantasmatic status”. In other words, any representation of gender outside the traditional binary highlighted the fact gender was a social construct. Disruptions to that illusion caused what they referred to as gender trouble.

Judith Butler was also interested to what extent “identity” was simply a descriptive feature of experience. If gender is a construct, can we construct it differently?

French Feminist Theory

Finally, Judith Butler carefully compared two French feminists and their thoughts on gender. First, Luce Irigaray who claimed there was only a masculine identity which “elaborates itself in and through the production of the ‘Other’”. By contrast, Monique Wittig argued only the feminine identity was defined because the masculine remained “unmarked and synonymous with the ‘universal’”.

Although these two critical perspectives seem very different, they are both based on the structuralist concept of binary opposition. In terms of traditional gender identities, binary opposition suggests a pair of ideas can only be understood by their relationship to each other, so gender masculinity and femininity are defined by their contrast.

Importantly, there is often an imbalance of power between the two concepts. According to the post-structuralist thinker, Jacques Derrida, “one of the two terms governs the other”. Both Irigarary and Wittig acknowledge this disparity between masculinity and femininity, but disagree on the process which produces the difference.

These two perspectives are certainly worth further consideration so try to apply them to your own experiences.

Your Behavior Creates Your Gender

Judith Butler brilliantly explains their views on gender and performance in a piece for Big Think. If you want to develop your understanding of the important concept, you have to watch this video.

The Constructionist Theory of Representation

Stuart Hall’s work on representation focused on the way meanings are not inherent in language or images, but is constructed through a complex process of selecting, organising, and interpreting information. Emphasising the role of ideology in this process of representation, Hall argued dominant cultural values and beliefs are often naturalised and taken for granted, so we need to resist messages which are hurtful and damaging, especially towards minority and marginalised groups.

Do we just assume Robert Pattinson is a brutish thug because he has a bruised face, spiky hair and wears a heavy chain around his neck? Or that Jonathan Bailey is a suave and sophisticated man ready to make his mark on the world because of his tailored clothes? Perhaps our interpretation of both men depends on our attitudes towards social class.

GQ and Masculinity

In her analysis of feminist discourse, Liesbet van Zoonen (1996) noted masculinity was often defined as individualistic, ruthless, and combative. This gender stereotype was repeated so much in the media it seemed “natural”. However, she also argued gender was a construct and roles will depend on the cultural and historical context.

Perhaps GQ’s focus on male beauty and grooming routines challenges the traditional stereotypes of masculinity. David Gauntlett (2008) certainly believed there was a fluidity of identity when it came to representations of masculinity in the media, including men’s magazines. GQ seems to support his opinion. However, the media theorist also recognised the editors found “excuses to photograph actresses and models in little clothing”, epitomised by Jessica Biel on the cover of the July 2007 issue, and the magazine appealed to “a sense of male specialness with expensive cars, meals, hotels, shoes, grooming products, suits and property”.

If GQ is ideologically dissident in its assumptions about masculinity, it is limited to what the publisher thinks will be accepted by its target audience.

Essay Questions

- To what extent does the representation of gender in magazines embody the dominant values and ideologies in society?

- Explain how the magazine’s emphasis on male beauty and grooming challenges some conventions of traditional stereotypes of masculinity.

- “GQ is a magazine for posh blokes”. Evaluate the usefulness of bell hooks’ concept of intersectionality in understanding the audience’s use of the Close Study Product GQ.

- Albert Bandura suggests audiences develop behaviours and attitudes through modelling by the media. Explore this idea in relation to the Close Study Product GQ.

- Explore how magazines use genre to attract audiences. You should refer to the Close Study Product to support your answer.

- To what extent are editorial decisions influenced by the magazine’s relationship with advertisers?

- How useful are Tzvetan Todorov’s concepts of equilibrium and repair in understanding the narratives in this magazine?

- Explore how GQ continues to engage audiences despite competition from new digital technologies.

Bibliography