List of Key Actors

Faye Dunaway – Bonnie Parker. Faye Dunaway’s career began in the 1960s, in which she was a famous Broadway star. She made her on screen debut in 1967 in ‘The Happening’, the same year she made ‘Hurry Sundown’, alongside Michael Caine and Jane Fonda. Her role as Bonnie Parker made her an instant star and she received her first Academy Award nomination for it too. Her casting for the role proved to be difficult, as not only were many actresses that were being considered for the role, such as Jane Fonda, Tuesday Weld and Natalie Wood, but also producer Warren Beatty was not sold on her casting in the role, and had to be convinced by director Arthur Penn to allow the casting. He quickly came round to her after seeing some photographs of Dunaway taken on a beach by Curtis Hanson, claiming, “She could hit the ball across the net, and she had an intelligence and a strength that made her both powerful and romantic.”

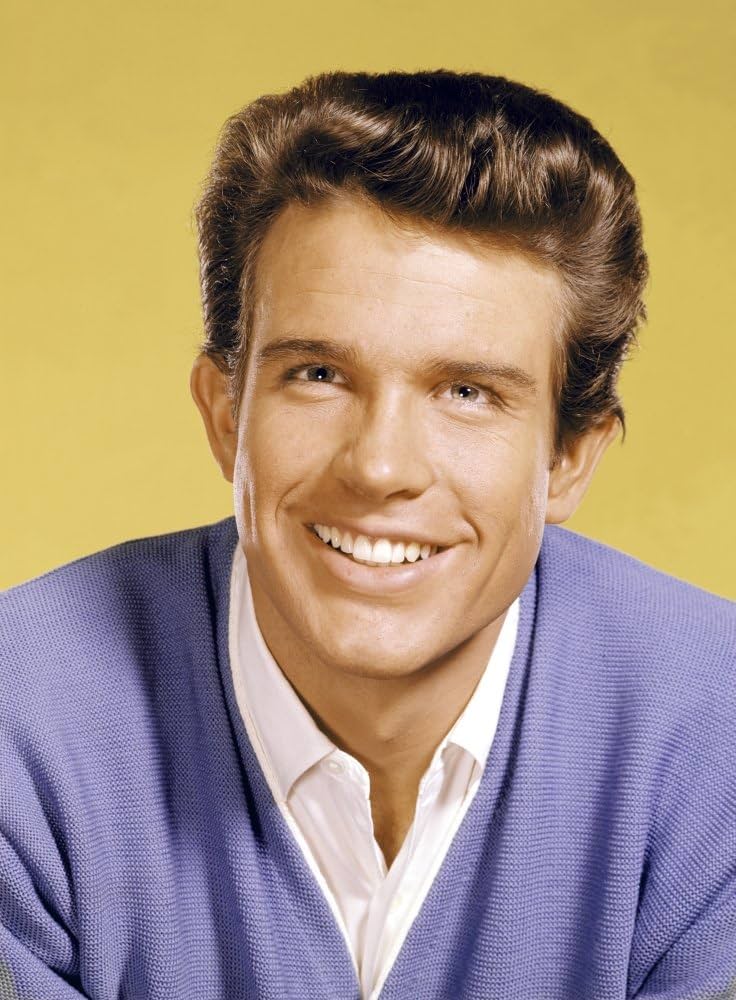

Warren Beatty – Clyde Barrow. Warren Beatty started his career in television shows such as ‘Studio One’ (1957), ‘Kraft Television Theatre’ (1957), and ‘Playhouse 90’ (1959) and he was also a semi-regular on the show ‘The Many Loves of Dobie Gills’ during its first season (1959-1960). His performance in William Inge’s ‘A Loss Of Roses’ on Broadway, his only Broadway performance, garnered him a 1960 Tony Award nomination for Best Featured Actor in a Play and a 1960 Theatre World Award. After this, he then enlisted in the California Air National Guard in February 1960 but was discharged the following year due to a physical inability. Beatty made his film debut in Eliza Kazan’s ‘Splendor in the Grass’ (1961). The film was a major critical and box office success and Beatty was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor and received the award for New Star of the Year. The film was also nominated for two Oscars, winning one. He didn’t really have another major success until ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ in 1967, in which he starred in and produced. The film was nominated for ten Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actor, and seven Golden Globe Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actor. Beatty was originally entitled to 40% of the film’s profits but gave 10% to Penn, and his 30% share earned him more than US$6 million.

Michael J. Pollard – C.W. Moss. Pollard’s on screen career began in television in 1959, in which he had appearances in programs such as, ‘The Human Comedy’ and ‘DuPont Show of the Month’. He then made his Broadway debut in a non-singing role he created in ‘Bye Bye Birdie’, as Hugo Peabody. It was in Broadway that he starred alongside Warren Beatty, who he already knew from his days in television. The two developed a close friendship, with Warren Beatty saying the reason he was cast in Bonnie and Clyde was because “Michael J. Pollard was one of my oldest friends”, Beatty said. “I’d known him forever; I met him the day I got my first television show. We did a play together on Broadway.” Pollard received Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations for Best Supporting Actor for his role in ‘Bonnie and Clyde’, as well as winning a BAFTA Award for Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles.

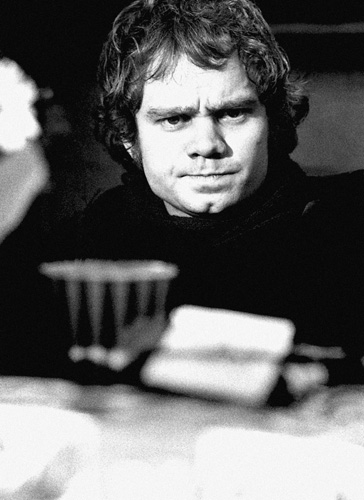

Gene Hackman – Buck Barrow. In 1956, Hackman began pursuing an acting career and joined the Pasadena Playhouse in California, where he befriended another aspiring actor, Dustin Hoffman. Hackman got various bit roles, such as a role in the film ‘Mad Dog Coll’ and on the TV series ‘Brenner’ and in 1963 he made his transition into Broadway in ‘Children From Their Games’, which only had a short run. However, his next Broadway performance, ‘Any Wednesday’ with actress Sandy Dennis in 1964, was a huge success and is what opened the door for his acting career to begin. He made film debut in ‘Lilith’, with Jean Seberg and Warren Beatty in the leading roles. His performance in ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ as Clyde’s brother Buck Barrow was described by Warren Beatty as ‘the most human performance he’d ever seen’ and it earned his first Academy Award nomination but it wouldn’t be until his role as Detective Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle in ‘The French Connection’ that he would win his first Academy Award for Best Actor, and thus, shoot into stardom. He then appeared in critically acclaimed films such as ‘Poseidon Adventure’, ‘Scarecrow’, alongside Al Pacino, Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘The Conversation’ and , a personal favourite of mine, ‘Mississippi Burning’.

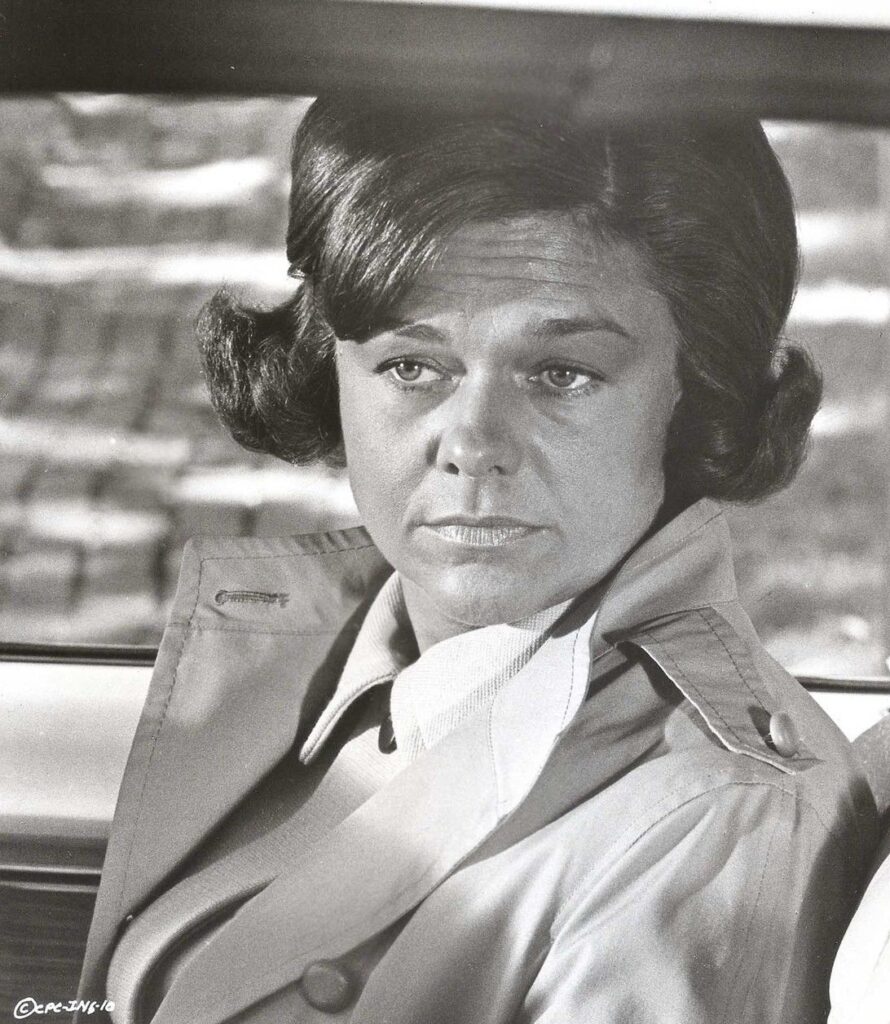

Estelle Parsons – Blanche. Parsons career began when she moved to New York and worked as a writer, producer and commentator for ‘The Today Show’. She made her Broadway debut in 1956 in the ensemble of the Ethel Merman musical ‘Happy Hunting’. Her Off-Broadway debut was in 1961, and she received a Theatre World Award in 1963 for her performance in ‘Whisper into My Good Ear/Mrs. Dally Has a Lover’. In 1964, Parsons won an Obie Award for Best Actress for her performance in two Off-Broadway plays, ‘Next Time I’ll Sing to You and In the Summer House’. In 1967, she starred with Stacy Keach in the premiere of Joseph Heller’s play ‘We Bombed in New Haven’ at the Yale Repertory Theatre. Obviously, she also starred in ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ in 1967 as Buck Barrow’s lenient wife Blanche. For this role, she won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. She also went on to be nominated in the same category for her role in ‘Rachel, Rachel’ and win a BAFTA Award Nomination for her role in ‘Watermelon Man’ in 1970.

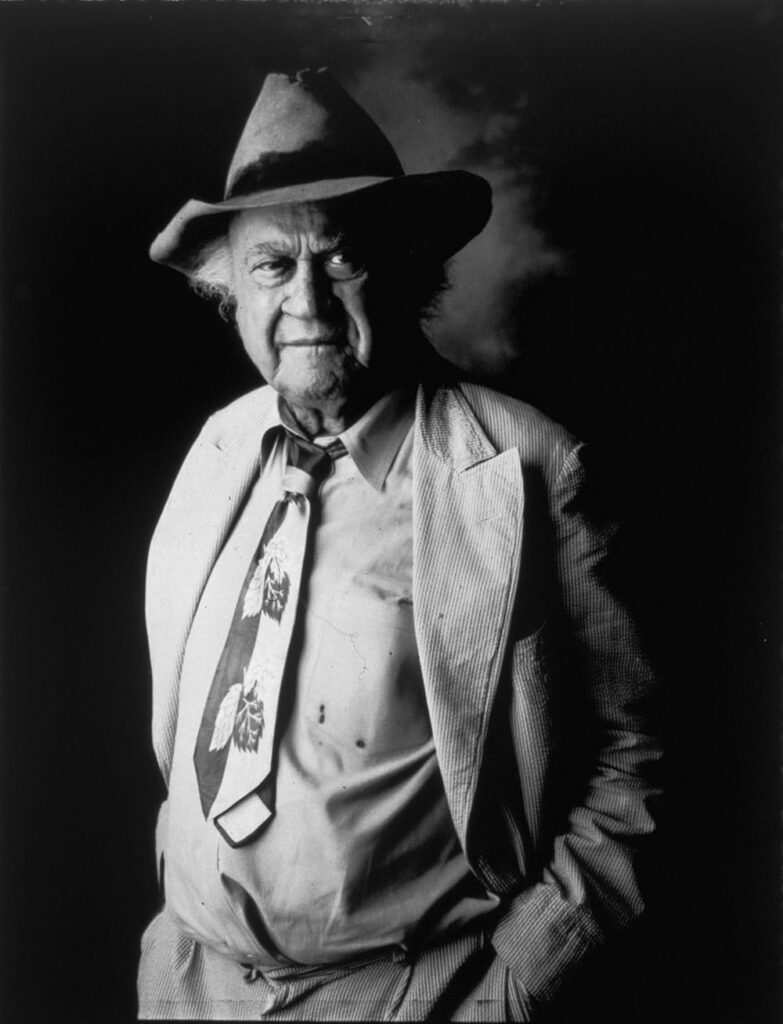

Denver Pyle – Frank Hamer. Denver Pyle’s on-screen career began in 1951, in which he guest-starred in the syndicated television series ‘The Range Rider’ with Jock Mahoney and Dick Jones. Up until his most well-known role of Uncle Jesse Duke in the CBS series ‘The Dukes of Hazzard’ (1979 – 1985), in which he did 146 episodes, he mainly had limited roles in his television and film career, most of which came in Western Tv series, such as his guest appearances in ‘My Friend Flicka’, ‘ The Restless Gun’ with John Payne, the syndicated Western series ’26 Men’, in which he appeared alongside Grant Withers in a episode titled ‘Tumbleweed Ranger’ and his several appearances in Richard Boone’s CBS show ‘Have Gun – Will Travel’, in which he was a variety of characters, including the character ‘The Puppeteer’ in the his final appearance on the show. Also, a lot of his apperances in film and tv were uncredited, such as his appearance in ‘Cheyenne Autumn’ in 1964 as Senator Henry and his appearance in ‘Home from the Hill’ as Mr Bradley in 1960, so clearly he wasn’t viewed as a major star. His most memorable role in film is probably his portrayal of Frank Hamer, the sheriff who tails Bonnie and Clyde for so long and is the final one to kill them in an ambush.

Dub Taylor – Ivan Moss. A vaudeville performer, Taylor made his film debut in 1938 as the cheerful ex-football captain Ed Carmichael in Frank Capra’s ‘You Can’t Take It with You’. He secured the part because the role required an actor who could play tuned percussion. In 1939 he appeared in the western film ‘Taming of the West’ in which he played a character named Cannonball, who was a comedic sidekick to other famous western character Wild Bill Elliot. He would play this character in 13 different films, such as the ‘Red Ryder’ series of films. He then had bit parts in the classic films ‘Mr Smith Goes to Washington’ (1939), ‘A Star Is Born’ (1954) and ‘Them!’ (1954). He later joined Sam Peckinpah’s stock company in 1965’s ‘Major Dundee’, playing a professional horse thief. After this he would then go on to play Ivan Moss in ‘Bonnie and Clyde’, a character who is deceivingly nice to the two main title characters, but behind their backs is signing their lives away to Frank Hamer, the sheriff who’s been tailing them for so long.

Gene Wilder – Eugene Grizzard. Gene Wilder’s professional acting career began in 1951 when he was cast as the Second Officer in Herbert Berghof’s production of ‘Twelfth Night’. He also served as the production’s fencing choreographer. After he joined the Actors Studio in 1958, he started to be noticed in the off-Broadway scene, thanks to performances in Sir Arnold Wesker’s ‘Roots’ and Graham Greene’s ‘The Complaisant Lover’, for which Wilder received the Clarence Derwent Award for Best Performance by an Actor in a Nonfeatured Role. One of Wilder’s early stage credits was playing the socially awkward mental patient Billy Bibbit in the original 1963–64 Broadway adaptation of Ken Kesey’s novel ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ opposite star Kirk Douglas. His first role in film was in 1967 in ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ as the minor role of Eugene Grizzard, a somewhat sleezy banker who, along with his wife, is kidnapped by Bonnie and Clyde.

Mise-en-scene in Bonnie and Clyde

Locations

In terms of mise-en-scene in Bonnie and Clyde, the locations that the film was done in definitely add to this aesthetic of realism and verisimilitude for the audience, as all the locations featured in the film are actually real and are in North Texas near DFW. An example of a real world location in the film is the cafe/convenience store scene in which Bonnie and Clyde have some lunch in this cafe/convenience store and then steal a car that is sitting outside. This cafe/convenience store is a real world cafe and is still standing on 100 Main Street, Lavon, Texas.

Another good example in terms of mise-en-scene in locations is the farm that Bonnie and Clyde are practicing their shooting, which they find out, once the former owner returns, has been repossessed by the bank. This location and that scene embody this feeling that Bonnie and Clyde aren’t actually that selfish and are robbing these banks to give back to the people. This aligns with the zeitgeist feel of the film that it embodies this New Hollywood glamorization of criminals and their heinous activities.

Costumes

The costumes used in this film definitely add to the film’s 1930s period piece aesthetic and certainly look like clothes that worn during that time, adding to the film’s realism and the versimilitude for the audience. The cast wears a vast array of clothing pieces that embrace the 30s, such as Clyde and Buck Barrow’s fedoras and brown tweed suits and Eugene Grizzard’s sleezy banker suit.

The one exception to this is Faye Dunaway’s outfit as Bonnie, as she wears very 60s clothes throughout the film and, once the film came out, her fashion choices in the film actually inspired a fashion movement, in which women started to wear berets and more smart suit jackets. And for me, the fact that Bonnie always has new and fashionable clothes aligns with this idea that she is quite a materialistic person and that she is quite selfish, unlike Clyde who is portrayed at moments throughout the film to be selfless.

Props

The props used in ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ once again add to the film’s realism and the versimilitude for the audience. Some particularly striking and realistic props in the film are the guns as they match the type of guns used in that time period and the cars used in the film as they are actual cars from that time period that were lent to the studio by this old car collector, with his only condition being ‘that they didn’t get damaged’.

Editing in Bonnie and Clyde

In terms of editing, a good sequence that sums the films French New Wave style of erratic editing is the opening sequence of Bonnie waking up, seeing Clyde trying to steal her mum’s car and then going down to confront him.

The unconventional formula of shots and erratic French New Wave-esque editing used within the sequence convey to the audience this idea that Bonnie feels trapped within her mundane, as shown by the shot that shows her lying on her bed with the bedstead bars casting shadows over her face, which imitate the image of prison bars.

The use of quickly zooming or panning to different shots, more specifically quickly zooming or panning to extreme closeups of her red lipstick covered lips or her eyes I imagine would make this opening feel very personal and imitate for the viewer and, along with the shots of her naked body, add to this powerful, sexual image that Bonnie has throughout the film.

And then, near the end of the sequence, this more conventional style of Hollywood editing starts to creep in, as it cuts between a low angle tilted up wards shots to show Clyde’s perspective, and high angle tilted down shots to show Bonnie’s perspective, which shows to the audience that these two are having a conversation. The switch to a more formulaic and conventional styling of editing may be done at this moment to show to the audience the switch in Bonnie’s mindset once she sees Clyde, going from ‘I’m stuck in this boring life’ to ‘Oh, perhaps this man is my way out of this life’.

Sound in Bonnie and Clyde

Dialogue

The dialogue in ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ I feel is very accurate to the time period in which the film is set, which adds to the film’s versimilitude and immersion for the audience. The use of words such as ‘momma’ and the character’s improper grammar in their speech certainly places the film in 1930s southern Texas. Also, the characters Texan accents certainly help the idea of the film being in Texas and that these people are from Texas.

Sound Motif/Score

The score within ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ can be at certain times very jovial and cartoonish, with the film’s recurring use of the song ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’ by Flatt and Scruggs certainly adding a quite comic tone to these rather morbid car chase scenes, especially the one in which a bank employee gets shot in the eye by Clyde Barrow, which creates a very clear contrast in tone. At other points in the film, the soundtrack adds to the mood of what is being shown, whether that be the somewhat romantic soundtrack that underscores the scene in which Bonnie and Clyde first have sex, or the scenes, which have a darker soundtrack to match the morbid content being shown.

Aesthetics in Bonnie and Clyde

Realism

‘Bonnie and Clyde’s realism is crafted impeccably in the film, whether it be through the real world locations being used in the film, or real 1930s cars being used in the film, to the actors Texan accents, the film certainly crafts it’s versimilitude and realism really well for the audience. However, it’s French New Wave style cinematography and editing, which is very jagged and erratic, unlike the conventional ‘invisible’ Hollywood editing, could certainly lessen the effect of the film’s brilliant realism for the audience

Tone

In terms of tone in Bonnie and Clyde, it certainly shifts a lot and the tone created by certain elements within a scene is certainly juxtaposing with one another.

A good example of this would be the scene in which Bonnie and Clyde’s gang rob a bank and one of the bank workers leaps onto the sideboards of the car and then gets shot in the eye, which then leads to a thrilling car chase/shootout with the police. The visuals being shown of this man being shot in the eye and this jovial bluegrass that underscores the scene certainly creates this clash in tone. The film makers have done this perhaps due to their French New Wave influences or maybe even perhaps to show the unpredictability of a criminal lifestyle.

Visual Style (French New Wave)

Bonnie and Clyde’s French New Wave influence is clear from the very beginning of the film, which uses this French New Wave style of erratic editing, to show to the audience that Bonnie feels trapped within her boring and mundane life.

The film uses many French New Wave tropes throughout, such as on location filming and not using built sets like Classical Hollywood does, and having very explicit and violent content throughout the film, such as Bonnie being nude in the film’s opening and the many shoot-outs and people being killed throughout the film. This French New Wave approach to Hollywood film-making certainly changed the landscape of Hollywood film and the world of film in general, as it allowed to film-makers to show more explicit content within their films, and it paved the way for more Hollywood films to be shot in real world locations, if it fit the film-makers direction and view of what they want their film to be.

Representations in Bonnie and Clyde

Women

In ‘Bonnie and Clyde’, there are two clear representations of women that being the two main female characters of Bonnie and Blanche.

The character of Bonnie I think can be looked at in two different ways. In one way, Bonnie represents the ‘Femme Fatale’, if you’re looking at this film as a piece of neo-noir, as throughout the film she attempts to manipulate Clyde with her attractive looks, such as the scene when they get back from the cinema and Bonnie pretends to be one of the dancers in the film and she tries to coerce Clyde. She also threatens to run away if she can’t see her mother. Another way you could look at her character is with a feminist viewpoint and you could view her as a character of female empowerment, as she robs the banks with the men and her sticking up to Bonnie could be seen as her standing for herself and want she wants, and could be viewed as not being manipulative. She is also the one to approach Clyde and seek a relationship with him and a change from her mundane life. A key scene which presents her as a visually powerful woman is when they are taking photos outside of Buck Barrow’s house, as in that scene, her clothing and the way she presents herself makes her look very domineering and powerful.

Bonnie also has this very clear cut powerful sexual energy from the beginning of the film, in which she is shown fully nude, though the audience don’t see it, which is a very forward thinking thing to include in a gangster film, as typically women within that genre of films only had background roles.

And the other female character in ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ is Blanche, who is represented as this very sceptical character, as she doesn’t want to get involved with Bonnie and Clyde and just wants to live a normal life with her husband, Buck Barrow. She could also be seen as representation of working class people as throughout the film she is seems to be quite scared of Bonnie and Clyde, which most likely was representative of the views real life everyday people had about Bonnie and Clyde at that time. She is definitely someone who is not suited to the criminal life, shown by her constant screaming at any bit of action throughout the film.

Throughout the film the two women express their distaste for one another, which isn’t very surprising as they are two very different types of women. This is expressed visually in the scene above where Bonnie is a smoking a cigarette and Blanche is not, and she is looking away from Bonnie, which shows the audience a clear visual divide.

Men

Within ‘Bonnie and Clyde’, a lot of the prominent characters are male, showing the society’s patriarchal status. There is quite of broad range of male characters shown in the film, with the more macho and brazen Buck Barrow and, at times, Clyde Barrow, as well as the sheriff who hunts them down who is quite macho and masculine, and you then have the much more timid, C.W Moss and his, in my opinion, rather timid and realistic minded father, Ivan Moss, who understandably doesn’t want Bonnie and Clyde in his house.

The portrayal of the title character Clyde Barrow by Warren Beatty is certainly an interesting one, as at certain points throughout the film, he is shown, in a counter typical way, to be caring towards Bonnie and at points is quite a timid and sensual man, refusing Bonnie’s sexual advances, saying ‘I ain’t no lover boy’. He is also portrayed in the film as someone who cares for the lower classes, as shown through the scene of him and Bonnie practicing their shooting on a repossessed farm, which is then interrupted by the previous owner, who, through Clyde giving him a gun, is able to kind of ‘stick it to the man’ and shoot in some windows on a property which was once his. This care for the lower classes is also shown when they’re robbing a bank and Clyde tells one of the old men to ‘keep your money pops…’, instead of give it into the bank. This portrayal of criminals in a good light is a zeitgeist for this turning point in cinema in which criminals were glamourized instead of shunned in the films that were being made.

Authority Figures

Authority figures are portrayed to be people who wish to thwart Bonnie and Clyde and their heinous acts, such as Frank Hamer, the vindictive sheriff who wishes to get revenge on Bonnie and Clyde after they humiliated him, and Ivan Moss, who doesn’t wish for Bonnie and Clyde to live in his home, and so crafts a plan with Frank Hamer. There is also this representation of the higher powers, such as the government, being against the working class people, which is shown through the scene of the farmer’s ranch being repossessed by the bank.

People of Colour

In terms of people of colour being represented in ‘Bonnie and Clyde’, there is barely any representation of that ethnicity, with the only major representation being the black man who is said to of ‘built this farm from the ground up’, with his white male friend, the first of which has been repossessed by the bank. Clyde allows him to shoot a couple of windows out in this kind of ‘stick it to the man’ moment.

This lack of representation of black people throughout the film is most likely a deliberate exclusion by Arthur Penn, as it helps place the audience’s mind into this era of segregated 1930s America, and adds to the film’s realism and versimilitude.

Working Class Americans

Working Class Americans in ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ are represented in two different ways. You have the migrant workers and families, who have been evicted from their homes, and the farmer, whose farm has been repossessed by the bank and you have the higher class banker Eugene Grizzard and his wife, who gets kidnapped by Bonnie and Clyde and their gang, and, after strangely getting to enjoy their company, get abandoned by on the side of a random road. The inclusion of these scenes and characters show to the audience what the wider public think of Bonnie and Clyde and, in Eugene’s case, what Bonnie and Clyde think of them.

The scene which features the migrant workers shows C.W. Moss bringing an injured Bonnie and Clyde to this group of migrant workers and asking them for water. They then, very selflessly, give C.W. Moss as much water as he wants, even though they themselves have very little. They then are astounded by the fact that they are helping Bonnie and Clyde. This plays into to this idea that Bonnie and Clyde do what they do to help out the working classes, which is also shown through the farm repossession scene. It also plays into the context of the time in which films were glamourizing criminal activity more often.

The scene which features Eugene Grizzard and his wife being captured by the Bonnie and Clyde gang, strangely getting along with them, and then suddenly being released also plays into this idea that Bonnie and Clyde are doing what they’re doing because they hate the ‘upper’ classes and they wish to help out those below them, which is why I think Bonnie suddenly turns on them, as I think she realises that they are quite well of people and that those aren’t the type of people they should be helping.

Political and Social Contexts in Bonnie and Clyde

In terms of contexts which the film ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ embody, it definitely has the spirit or the zeitgeist of this idea that younger people wish to see more exciting and relatable things in film, which is due to their exposure to the graphic content , specifically the Vietnam War ,through the news. This is seen in Bonnie and Clyde through the film’s overtly graphic and sexual content, for the time the film was made.

It also embodies this ‘New Hollywood’ film movement in which the ‘Old Hollywood’ factory system was pretty much gone and in its place came this idea that the directors should be allowed more freedom and should be given as much of the success of the film as the actors, which is why name such as George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola are so well known to people who aren’t massively versed in the world of film.

And finally, in terms of the films aesthetics, the film marks a change in which film editing and camera framing is done, as it goes from this very conventional ‘invisible’ style of editing and framing to this more erratic and much more obvious to the eye editing that is influenced by French New Wave directors, such as Goddard and Truffaut.