Claude Cahun (1894–1954)

Who:

Claude Cahun, born as Lucy Schwob in Nantes, France, was a pioneering photographer, poet, and writer. She adopted the name Claude Cahun as a gender-neutral persona, reflecting her resistance to societal gender norms and her exploration of identity beyond the binary. Cahun’s work was highly experimental, challenging conventional notions of gender, sexuality, and the self.

What:

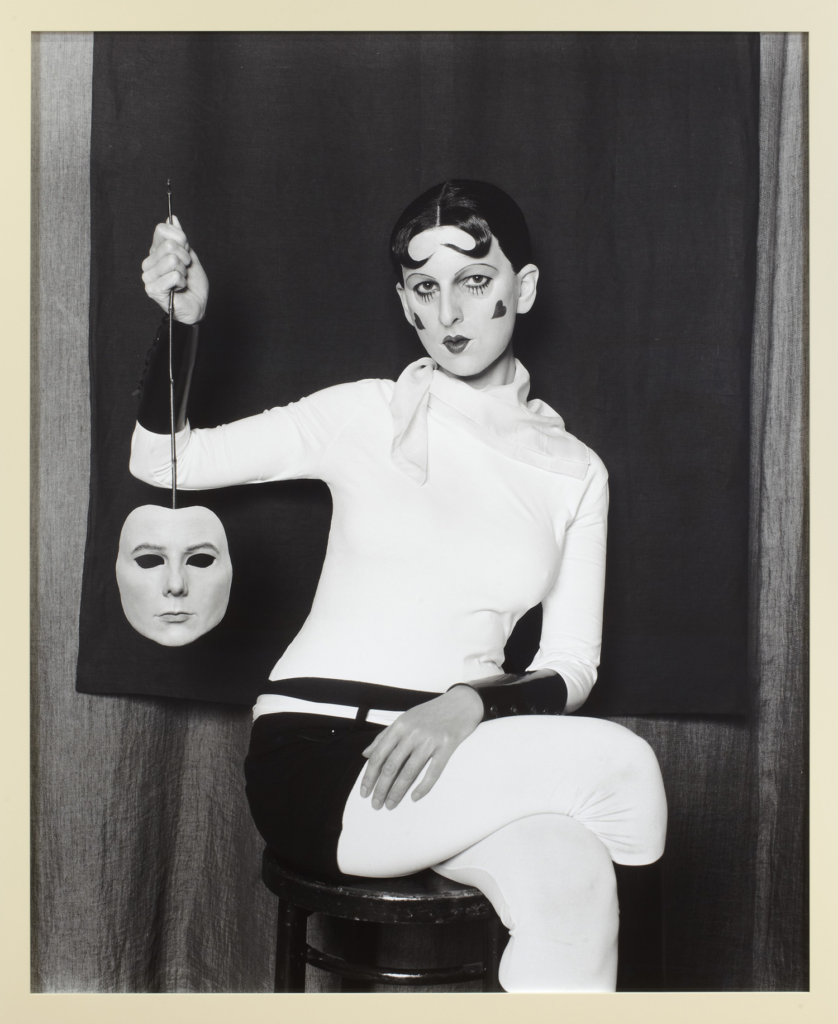

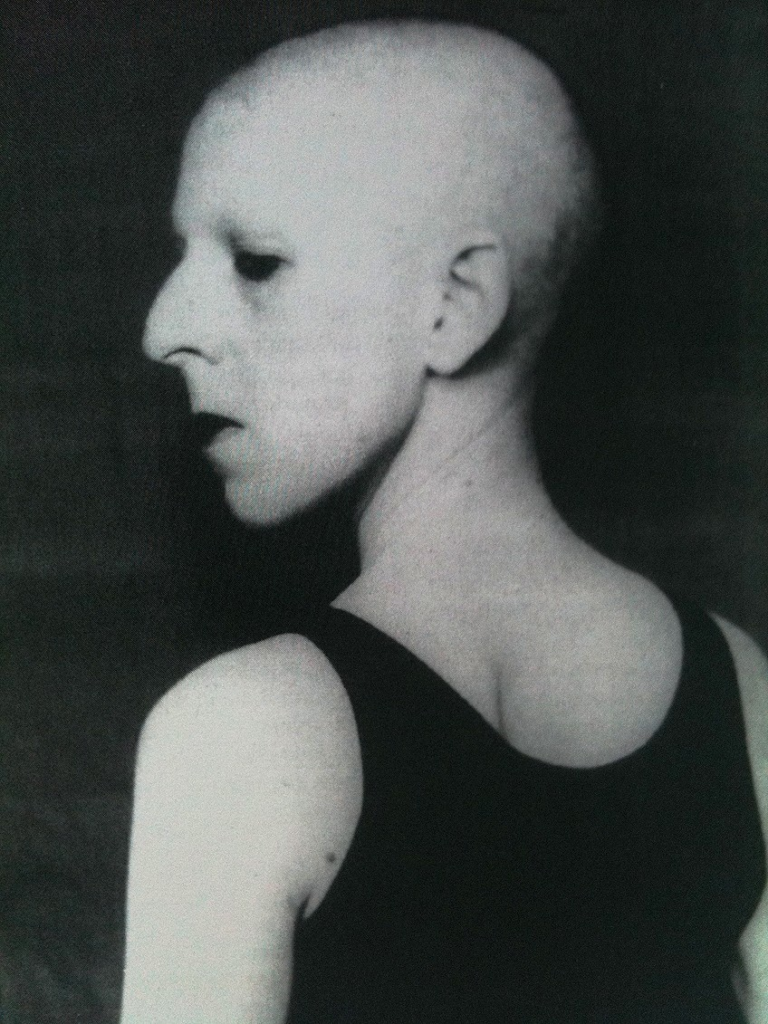

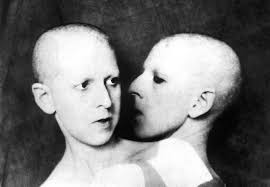

Cahun is best known for her self-portraiture, which she used as a tool for gender exploration and identity fluidity. She transformed herself into various personas using makeup, costumes, and props, blurring the lines between masculine and feminine. Her works often included surrealist elements, utilizing symbolic imagery and dreamlike compositions to challenge perceptions of reality and identity. Cahun’s photographs also explored the performative nature of identity, questioning how roles and gender are constructed.

When:

Cahun’s most significant photographic work was created in the 1920s and 1930s, during her involvement with the surrealist movement in Paris. Her later works, particularly during the 1940s, became politically charged as she and her partner, Marcel Moore, were involved in resistance activities during World War II.

Where:

Born in Nantes, France, Cahun moved to Paris during the 1920s, where she became part of the avant-garde and surrealist circles. In the late 1930s, she and Moore relocated to the Channel Island of Jersey, where they lived during the German occupation in WWII. It was in Jersey that Cahun’s work took on a more political tone as she used photography for resistance propaganda.

How:

Cahun’s photography was deeply performative, with the artist using herself as the subject to create multiple constructed personas. She utilized props, costumes, and makeup to transform her identity, playing with gender ambiguity and challenging the traditional notions of the feminine and masculine. Her works often included surreal, dreamlike compositions and symbolic imagery. Cahun’s approach to self-portraiture was collaborative, particularly with Marcel Moore, who assisted in capturing many of her most iconic works.

Why:

Cahun’s photography was a direct challenge to societal norms around gender and identity. By using self-portraiture as a tool for experimentation, she questioned the fixed nature of gender roles and explored how identity is shaped by culture. Cahun’s work, much of which was feminist in nature, critiqued the traditional expectations placed on women and offered an early commentary on gender fluidity and sexuality. Her photographs also explored the performative aspects of identity, positioning her as a significant figure in the history of self-representation and early critiques of fixed gender norms.

MOODBOARD

World war II activism

In 1937, Cahun and Moore moved to Jersey, where they became active in resisting the German occupation during World War II. Opposed to war, they produced anti-German propaganda, including rhythmic poems and critical messages derived from BBC reports on Nazi atrocities. Using the pseudonym Der Soldat Ohne Namen (The Soldier With No Name), they secretly distributed these flyers at German military events, placing them in soldiers’ pockets, on chairs, and in cars. One notable act was hanging a provocative banner in a church that mocked Hitler’s authority. Their resistance was not just political, but also artistic, reflecting their desire to challenge and undermine authority.

In 1944, they were arrested and sentenced to death, but the sentence was never executed due to the liberation of Jersey in 1945. Despite this, Cahun’s health suffered from her imprisonment, and she died in 1954. During her trial, she reportedly told the German judge that they would have to shoot her twice, as she was both a resistor and a Jew, which led to laughter in the courtroom and may have saved her life. Cahun and Moore are buried together in St Brelade’s Church. Their resistance efforts were a deeply personal, lifelong fight for freedom.

LEGACY

Claude Cahun’s work, which remained largely unrecognized during her lifetime, has since gained significant attention for its social critique and revolutionary impact on art and gender norms. She used her photography and writing to challenge societal expectations, particularly those related to gender, beauty, and logic, destabilizing conventional notions of reality. Cahun’s involvement in the Surrealist movement added new perspectives, especially with her portrayal of women not as erotic symbols but as fluid, gender-nonconforming figures. Her work has been described as “prototransgender,” with some considering her a precursor to modern trans self-representation.

Cahun’s life and legacy have gained renewed recognition in recent years. A street in Paris was named after her and her partner Marcel Moore in 2018. Cahun’s WWII resistance work, along with Moore’s, was highlighted in the 2020 book Paper Bullets. She was also honoured by Google in 2021 with an animated Doodle for her birthday. A novel based on her life, Never Anyone But You, was published in 2018, and in 2023, a graphic novel about her life, Liberated: The Radical Art and Life of Claude Cahun, was released, further exploring her artistic and political activism.

Image Analysis

Visual Aspects

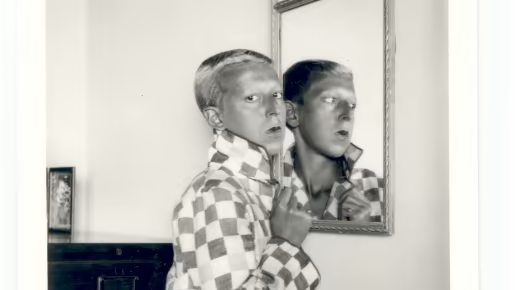

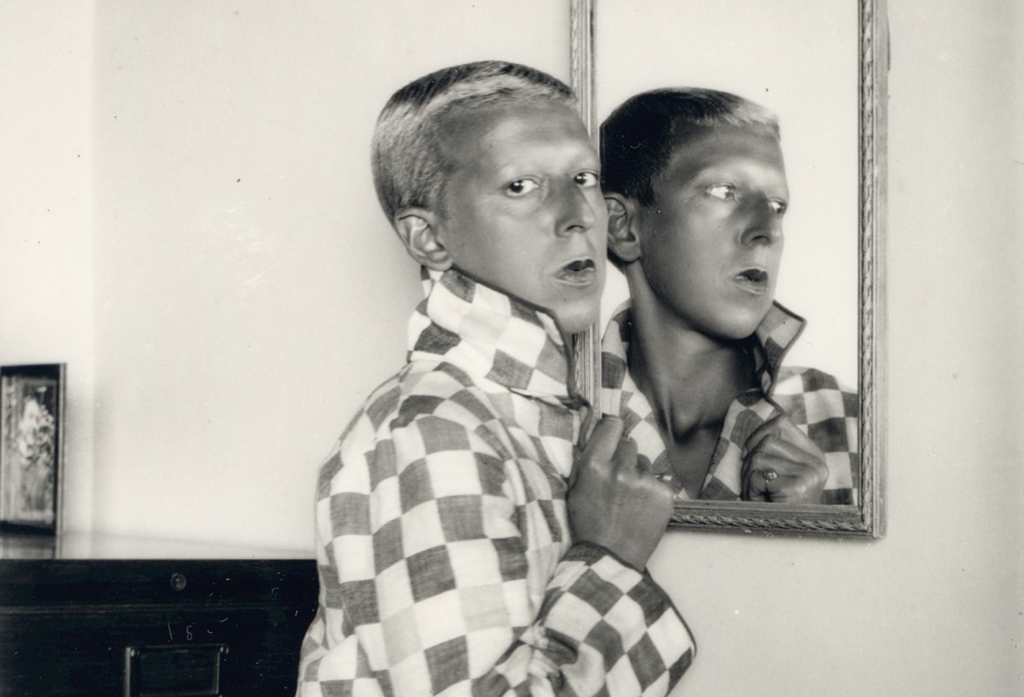

Claude Cahun’s black-and-white self-portrait immediately draws you in with its strong composition and exploration of identity. The image is split between two versions of Cahun: her physical form on the left and her reflection in the mirror on the right. This duality feels deeply personal, almost like a visual representation between how she sees herself and how the world perceives her.

Her androgynous appearance is striking. The short hair, checkered shirt, and upturned collar challenge conventional ideas of femininity. The raised collar seems to suggest she’s hiding a part of herself, while the reflection, showing her bare neck, hints at a more vulnerable side. Creating a interesting contrast between what’s concealed versus what’s revealed.

Her serious expression adds emotional weight. She looks directly at the viewer, almost challenging us, yet she turns away from the mirror, as if rejecting her own reflection. The plain background keeps all the focus on her, amplifying the intensity of her presence and the interplay with the mirror.

Technical Aspects

The soft, natural lighting in this photo enhances the fluency of the photograph , Shadows are gentle, giving depth to her face and texture to her clothing. The absence of harsh contrasts makes the image feel intimate and smooth.

The composition feels deliberate, with the mirror perfectly aligned to create balance. The camera is at eye level, making the connection between Cahun and the viewer feel direct and personal. Her sharp focus ensures both she and her reflection demand equal attention, forcing us to at least acknowledge the tension between the two.

Conceptual Aspects

This portrait is a conversation about identity, duality, and self-perception. Traditionally, mirrors in art symbolize vanity or beauty, but here, Cahun flips the script. She doesn’t admire her reflection. she seems to reject it. Her pose suggests discomfort with what the mirror reveals, yet she confronts the viewer head-on, as though asking us to consider the same questions about identity.

The raised collar adds layers to this narrative. It hints at concealment. something she’s choosing not to show us. But the mirror exposes her neck, a symbol of vulnerability and openness. This interplay between hiding and revealing feels universal. Highlighting the internal conflicts we all face about how much of ourselves we show to the world.

Cahun’s choice of clothing and androgynous style were radical for her time. By rejecting societal expectations of femininity, she challenges us to think about gender as something fluid , not as a fixed and deeply cemented concept. This bold self-representation speaks to themes that feel just as relevant today as they did during her time, as she battles her own physical reality with how she really feels.

Contextual Aspects

Cahun created this photograph in the early 20th century, a time when gender roles were rigid and societal expectations weighed people down heavily. As a French artist associated with Surrealism, she was part of a movement that loved to explore dreams, illusions, and hidden truths. This aligns perfectly with her use of mirrors to delve into identity and self-perception.

During this period, photography was gaining traction as an art form, and Cahun used it not just to create striking images but also to push boundaries. Her work feels like a quiet rebellion/ refusal to conform to the era’s strict ideas of gender and identity.

Emotional Response

Looking at this photograph, you can’t help but feel a mix of unease and empathy. The direct gaze pulls you in, almost demanding your attention, while the turned-away reflection creates a sense of conflict. It’s as if Cahun is wrestling with self-acceptance, a struggle that feels both deeply personal and universally human.

The raised collar and the mirror deepen this emotional tension. They remind us of the parts of ourselves we keep hidden and the vulnerability of having them exposed. Her serious expression feels heavy, as though she’s carrying the weight of these questions. questions we might ask ourselves, too. In the end, the portrait leaves you thinking about the complex, often contradictory nature of identity, making it as impactful today as it was then.

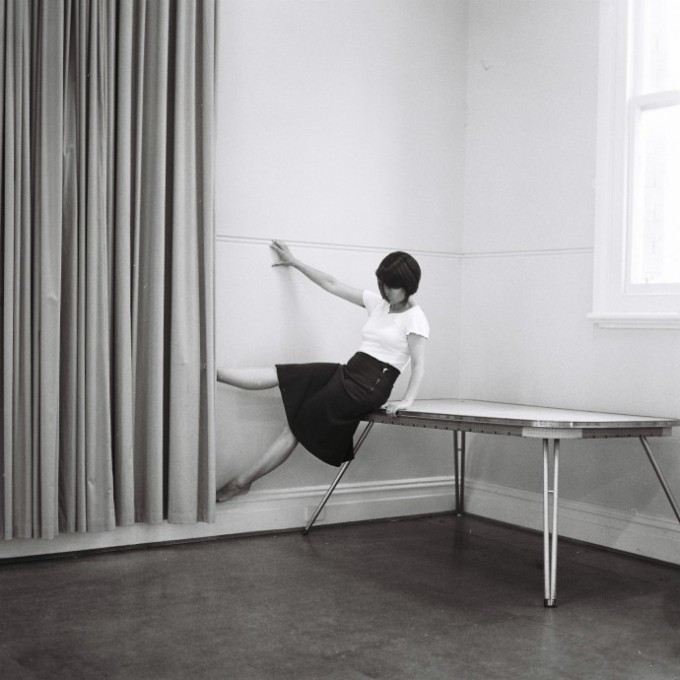

Clare Rae: Exploring the Body, Landscape, and Performance

Melbourne-based artist Clare Rae is known for her evocative photographs and moving image works that challenge traditional representations of the female body by exploring its relationship with physical environments. In 2017, Rae participated in the Archisle International Artist-in-Residence programme in Jersey, where she delved into the Claude Cahun archive. During her residency, she created new photography and film, ran workshops, and examined Cahun’s connections to Jersey’s cultural and physical landscapes.

Her residency culminated in the creation of the series Entre Nous (Between Us): Claude Cahun and Clare Rae, which debuted at the Centre for Contemporary Photography in Melbourne (March 22–May 6, 2018) and later exhibited at CCA Galleries in Jersey, UK (September 7–28, 2018). Accompanying the series, Rae published Never Standing on Two Feet in April 2018, featuring an introduction by Susan Bright and an essay by Gareth Syvret.

Never Standing on Two Feet: A Feminist Perspective on Landscape and Identity

In this series, Rae investigates how Claude Cahun’s engagement with Jersey’s landscapes shaped her work, particularly in relation to its coastal geography and Neolithic ritual monuments. Rae reflects:

“Like Cahun’s, my photographs depict my body in relation to place; in these instances, sites of coastal geography and Jersey’s Neolithic ritual monuments. I enact a visual dialogue between the body and these environments and test how their photographic histories impact upon contemporary engagements.”

Rae builds on Cahun’s legacy of using self-portraiture to critique the male gaze, positioning her work as a feminist exploration of self-representation. Her practice integrates gesture and performance to reimagine the female body in landscapes, contrasting and unsettling traditional depictions.

Artistic Influences and Methodologies

In an artist talk, Rae contextualized her practice, drawing connections to artists such as Claude Cahun, Francesca Woodman, and Australian performance artist Jill Orr. She highlighted the role of performative photography in her work, where gesture and the body become tools for disrupting conventional narratives. Rae also discussed her engagement with architecture and the body, her methodologies for image-making, and the conceptual outcomes of her projects.

Her work invites viewers to reconsider the interplay between identity, landscape, and performance, building on historical contexts while addressing contemporary feminist concerns. For a deeper exploration of her process and its influences, see the blog post Photography, Performance, and the Body.

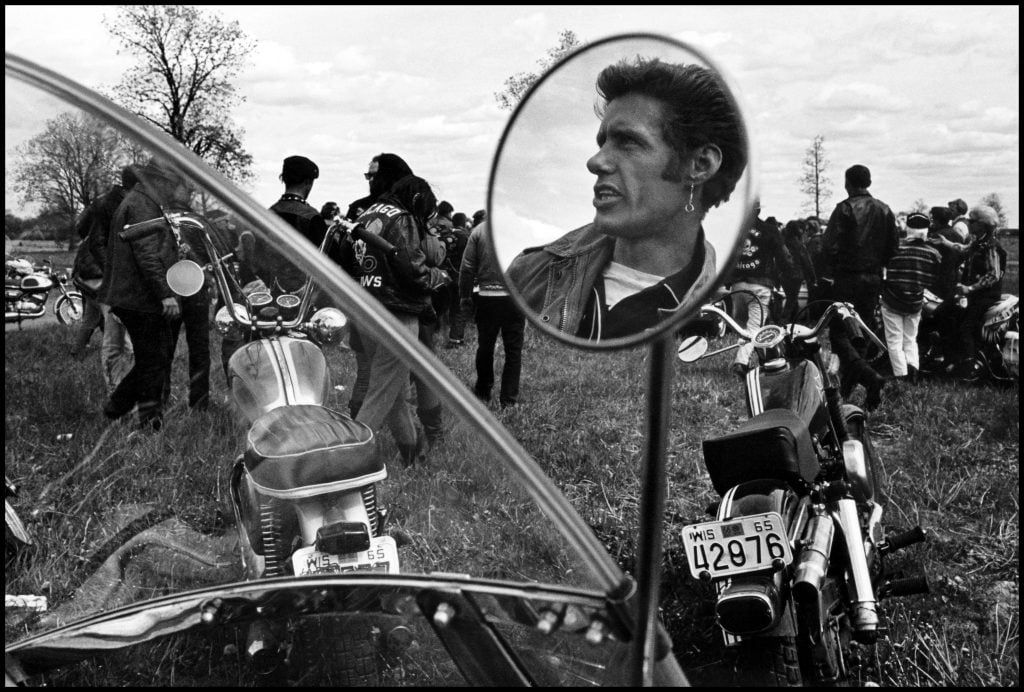

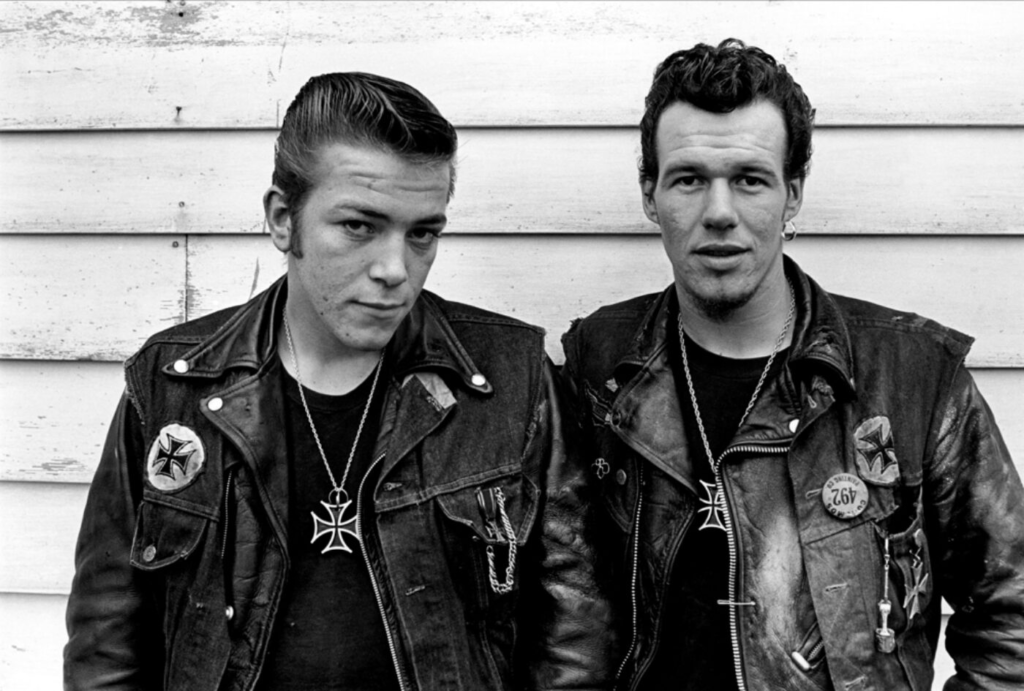

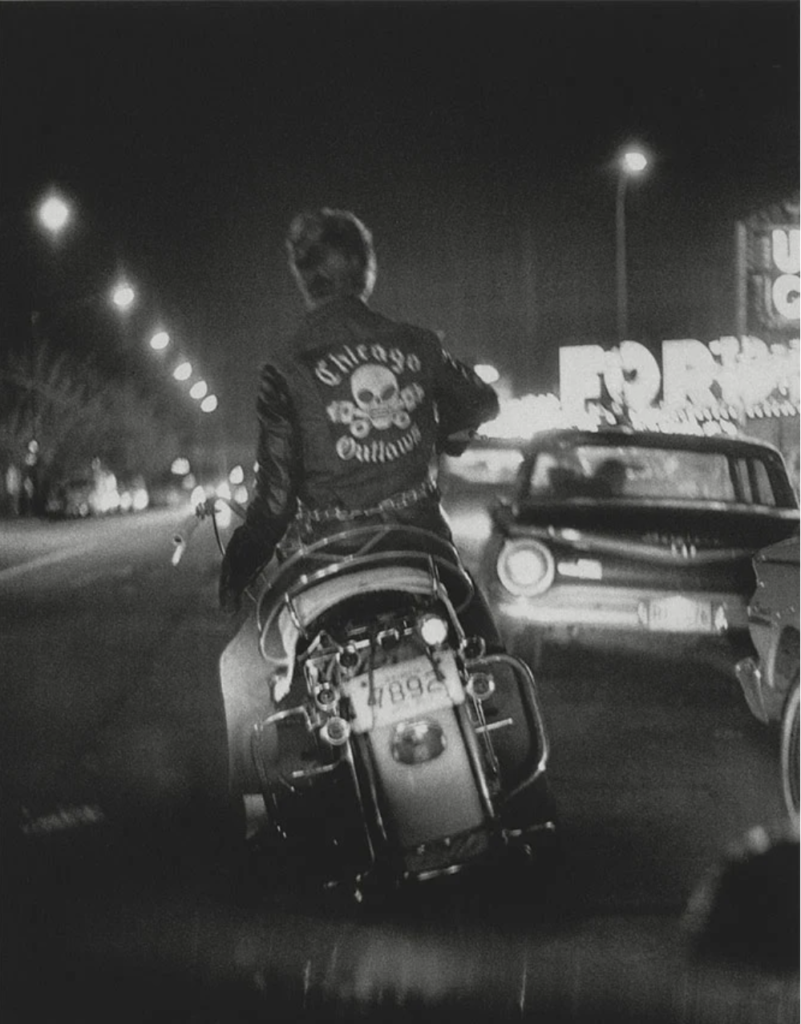

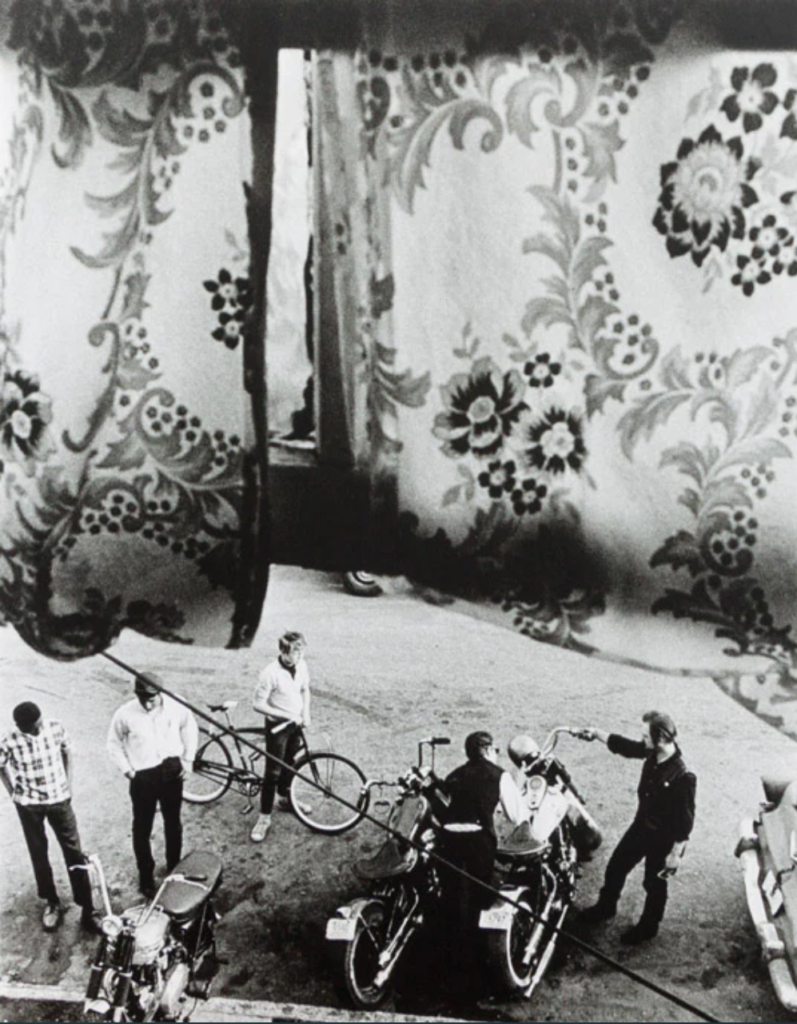

Danny Lyon is an American photographer and filmmaker. All of Lyon’s publications work in the style of photographic New Journalism, meaning that the photographer has become immersed in, and is a participant of, the documented subject. He is the founding member of the publishing group Bleak Beauty.

One of the most original and influential documentary photographers of the post-war generation, Danny Lyon forged a new style of documentary photography, described in literary circles as “New Journalism,” an unconventional, personal form of documentary in which the photographer immersed himself in his subject’s world.

Inspired by his work in Middle America, Lyon built a house in New Mexico, where he’s lived since 1970. Lyon continues to work, with his new book This is My Life I’m Talking About releasing in 2024

This is the artist which i will be basing my masculinity photoshoot on. It will be centrered around how motorbikes highlight masculinity and character