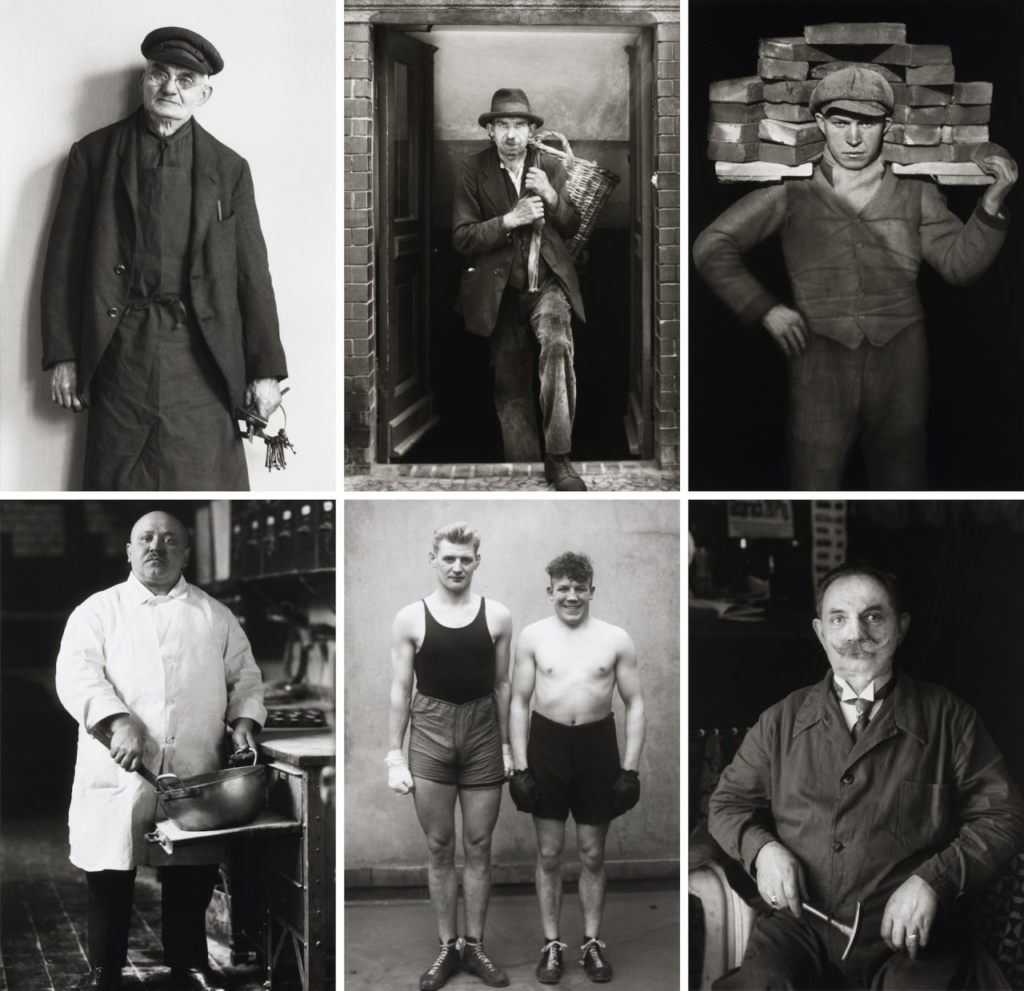

August Sander:

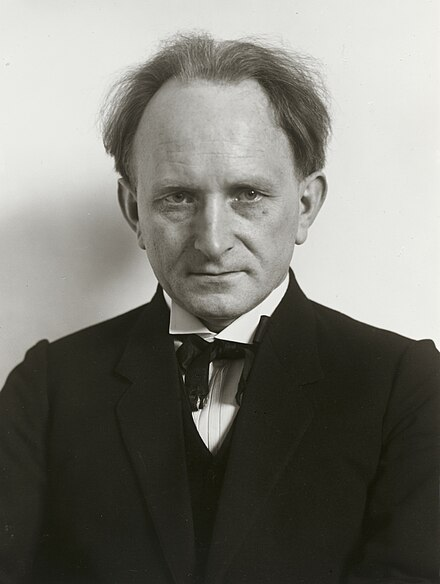

August Sander was a German photographer whose work documented the society he lived in. He was one the most-important portrait photographers of the early 20th century.

Short Bio:

The son of a mining carpenter, Sander apprenticed as a miner in 1889. Acquiring his first camera in 1892, he took up photography as a hobby and, after military service, pursued it professionally, working in a series of photographic firms and studios in Germany.

By 1904 he had his own studio in Linz, and, after his army service in World War I, he settled permanently in Cologne, where in the 1920s his circle of friends included photographers and painters dedicated to what was called Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity.

His Photographs:

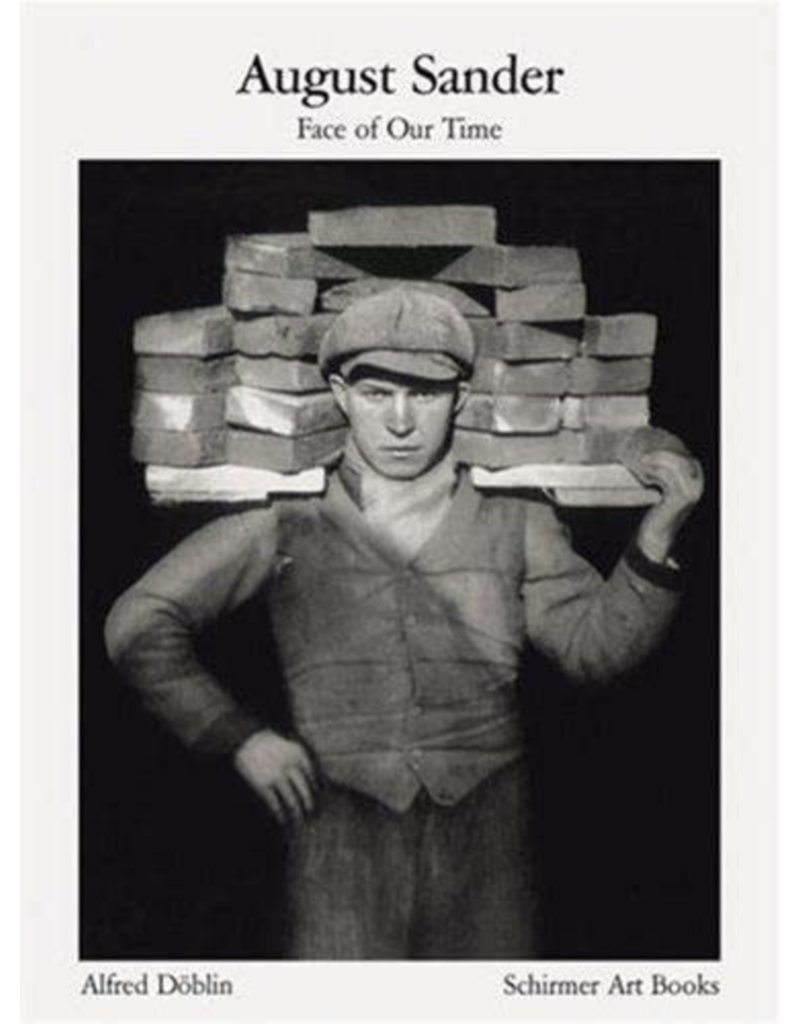

After photographing local farmers near Cologne, Sander was inspired to produce a series of portraits of German people from all strata of society. He was committed to ‘telling the truth’. His portraits were usually stark, photographed straight on in natural light, with facts of the sitters’ class and profession alluded to through clothing, gesture, and backdrop. At the Cologne Art Society exhibition in 1927, Sander showed 60 photographs of “Man in the Twentieth Century,” and two years later he published Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time), the first of what was projected to be a series offering a sociological, pictorial survey of the class structure of Germany.

Typologies:

Sanders was one of the first portrait photographer to produce a series of typological studies. ‘The Face of Our Time’ categorised his portraits according to their profession and social class, or ‘types’. As a typology, these photographs prioritized “collecting” rather than stand-alone images. They became a powerful method of revealing a photographic record of the people of his time.

The portraits:

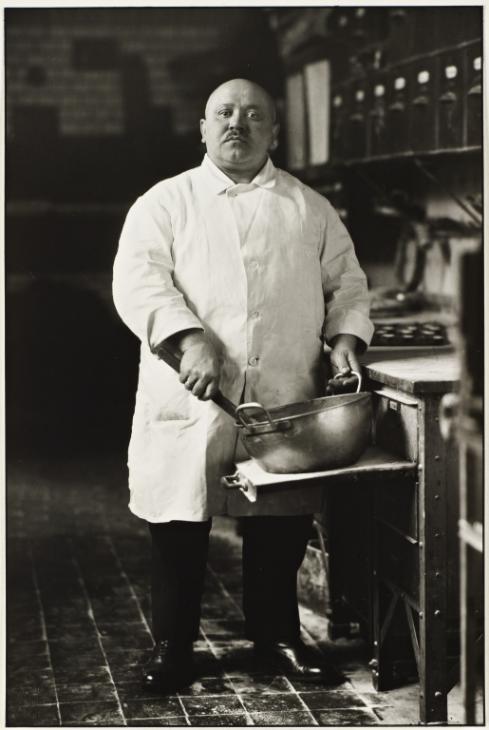

Sanders’ photographs are mostly black-and-white portraits of Germans from various social and economic backgrounds: aristocrats and gypsies, farmers and architects, bohemians and nuns. The portraits often include familiar signifiers (a farmer with his scythe, a pastry cook in a bakery with a large mixing bowl, a painter with his brushes and canvas, musicians with their instruments, and even a “showman” with his accordion and performing bear), but sometimes the visual clues to a subject’s “type” are not so obvious, leaving the title of the work and its placement in one of Sander’s categories to illuminate the subject’s role. The titles Sander assigned to his photographs do not reveal names, and capture one of the project’s many contradictions: Each photograph is a portrait of an individual, and at the same time an image of a type.

“Nothing seemed to me more appropriate than to project an image of our time with absolute fidelity to nature by means of photography,” he once declared.

“Let me speak the truth in all honesty about our age and the people of our age.”

During the war

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, however, Sander was subjected to official disapproval, perhaps because of the natural, almost vulnerable manner in which he showed the people of Germany or perhaps because of the diversity it revealed. The plates for Antlitz der Zeit were seized and destroyed. (One of Sander’s sons, a socialist, was jailed and died in prison.) During this period Sander turned to less-controversial rural landscapes and nature subjects. Late in World War II he returned to his portrait survey, but many of the negatives were destroyed either in bombing raids or, later in 1946, by looters.

Konfirmandin

In the early portraits such as ‘Konfirmandin (Confirmation Candidate)’, Sander portrays pastoral families in their Sunday-best, an insight on how these communities chose to present themselves to the camera.

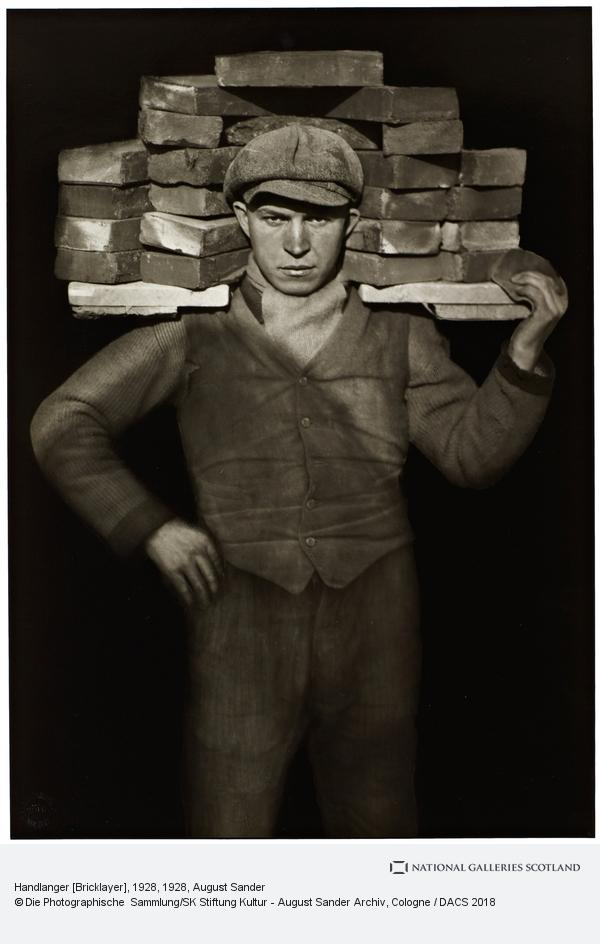

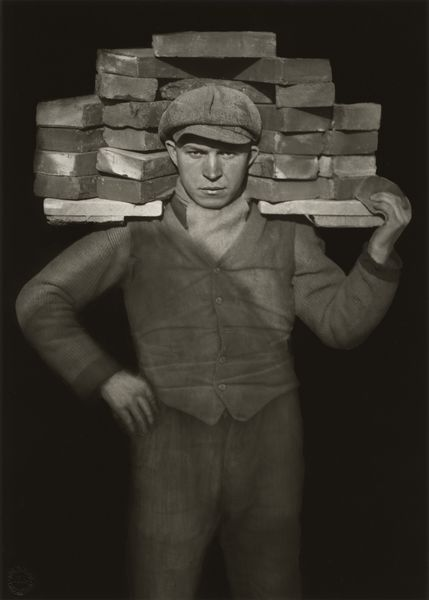

‘Handlanger (Bricklayer)’.

This photograph belongs to ‘The Skilled Tradesman’, one of seven chapters within his ‘People of the 20th Century’ project. The title and subject of this photograph form an archetype of Sander’s sociological documentation of people from a variety of occupations and social classes. Formally, the portrait’s centrality, flat background and conventional framing demonstrate Sander’s investment in photography as a ‘truth-telling’ device; one which represents reality as it is, without formal experimentation and within the boundaries of the history of photographic portraiture. Sander wrote in his seminal lecture ‘Photography as a Universal Language’ that photography was the medium most able to best reflect the ‘physical path to demonstrable truth and understand physiognomy’.

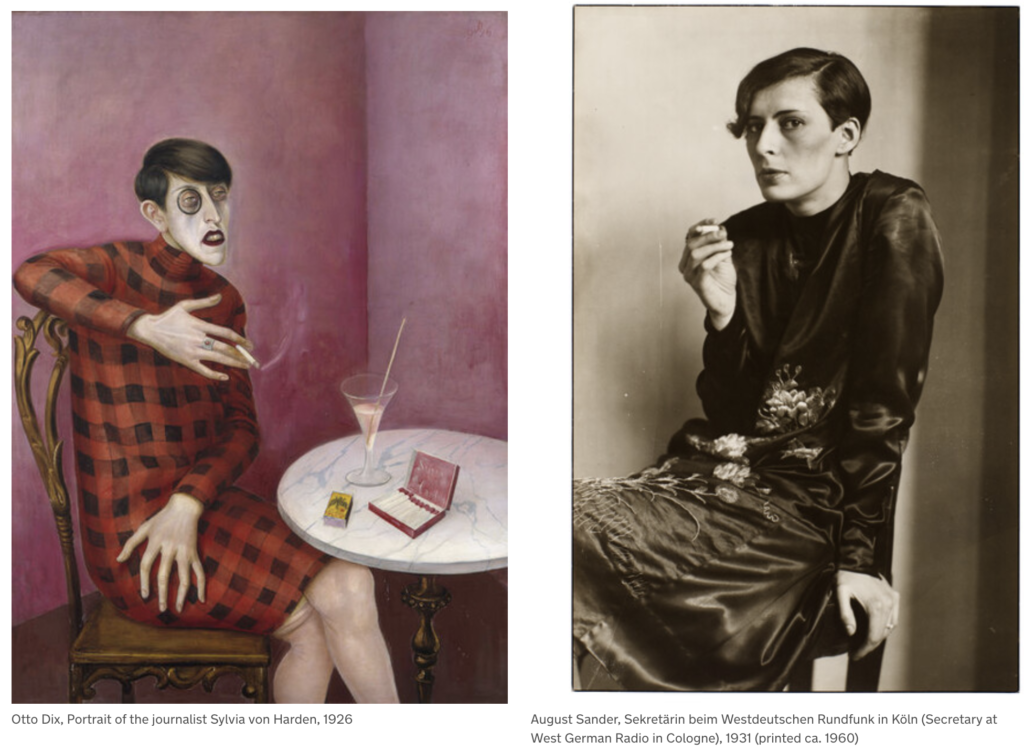

‘Sekretärin beim Westdeutschen Rundfunk in Köln (Secretary at West German Radio in Cologne)’,

When Sander developed People of the 20th Century, he included the group ‘The Woman’. Among these subjects is ‘Sekretärin beim Westdeutschen Rundfunk in Köln (Secretary at West German Radio in Cologne)’, photographed during his work for the German public broadcasting institution ‘Westdeutscher Rudfunk’. The portrait draws comparison to Otto Dix’s ‘Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden’ painted five years earlier. They both depict a new movement of women at work during the time—simultaneously androgynous and feminine, liberated from the domestic sphere. The portraits are important within the rise of the New Objectivity movement in German art—a reaction against the dominant style of expressionism—seeking a more objective and unsentimental portrayal of the human figure.

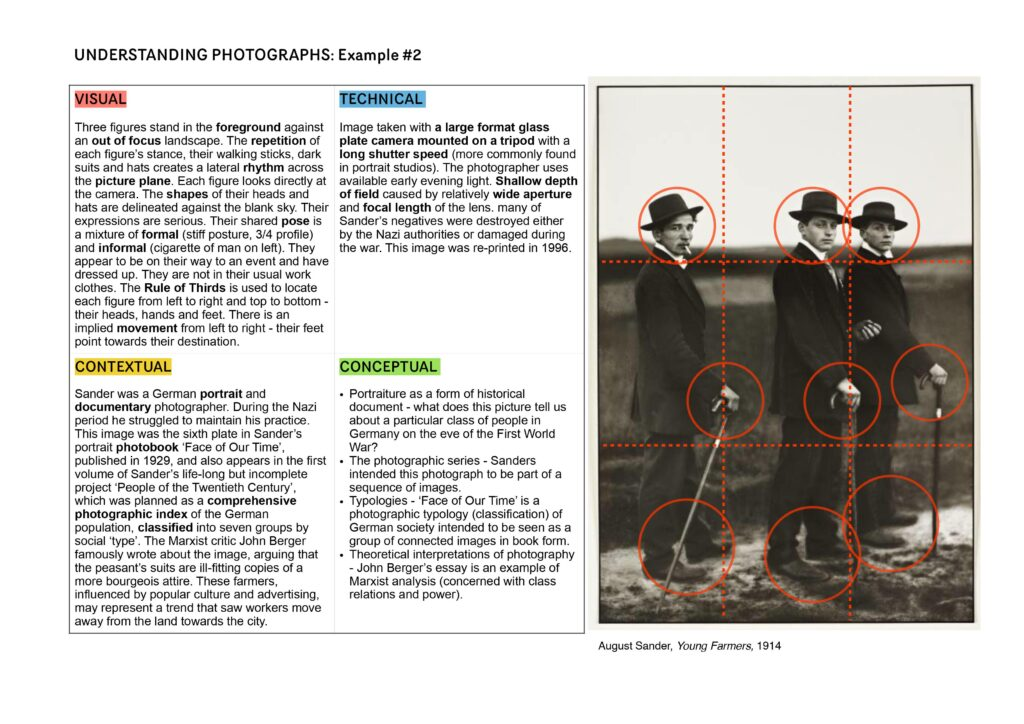

Image Analysis

Untitled image, from book: The face of our time, published in 1929

Subject:

This photo consists of an elderly man using his two walking sticks seen in the foreground. He appears to have paused while walking up the lane in the background. We can tell the man is old by his posture, bent and twisted around stiffly to face the camera, as well as the white facial hair.

The subject of the photo looks as if he has been walking along the road and has paused to face the photographer. The subject is positioned to the right of the frame, facing the centre of the frame and towards the negative space to the left. This draws our attention through the photograph to the building in the background, and gives a sense that this is where the man is walking to. His neutral expression gives a sense that this is a natural pose. As if this is not staged, but a photo of a man in his natural environment.

For me, I feel like Sander’s photographical types allow us to connect with the subjects. The eye contact with the camera lures us into the photo, in a neutral and unimposing manner. The subjects seem real, relaxed in their daily routine, and at home in the environment that surrounds them. The photo seems to celebrate everyday types of people, inviting us to get to know the essence of the person in the photo.

The environment:

The house in the background appears to be a traditional Tudor building featuring a façade with white stucco exteriors punctuated with decorative half-timbering or a dark brick-and-stone construction. The traditional building gives a sense that this is a charming and humble environment where the subject lives.

Visual:

This photograph, and all of Sanders’ photographs are black and white. While this is a result of camera limitations of the time, the monotone aesthetic contributes to Sanders’ typographical approach, making each photo appear like it belongs to the same colletion.

The monochromatic aesthetic also enhances the tonal values in the photograph. The dark tone of the shrubbery that sits to the right of the photo with the subject, contrasts the lighter pathway to the left, drawing your eye into the photo and towards the house.

The unkept and rustic texture of the shrubbery and pathway suggests that this is a rural area.

Leading Lines

The main leading line draws your attention from the bottom right corner of the page, up to the subject and then through to the house.

Furthermore, the angle of the walking sticks lead the eye directly to the subject’s face.

Balance:

The line created by the shrubs in the background and cut through the photo, divide the photo into two halves. The bottom half consists of the pathway, a more empty or negative space, to contrast the weight of the details in the top half of the photo.

Composition:

Looking closely it could appear that Sander has used the rule of thirds to construct this image. The subject sits on the intersection of the right third, while the house sits within the top left third. The subject occupies 2 thirds of the photo, making it the primary focus.

Angle:

The photo is taken from an eye-level direct perspective. This creates a more intimate connection between the subject and the viewer, it gives a very neutral eye.

Technical

This photo uses natural lighting, contributing to the genuine nature of the photograph. The balanced exposure is free from formal experimentation.

The large aperture in this photo creates a shorter depth of field, bringing our attention to the foreground of the photo – the subject.

Context:

This photograph is from Sanders’ book ‘Face of our time’. The book was first published in 1929, with a foreword by German writer Alfred Dublin. On its first publication, it was advertised as follows: “The sixty shots of twentieth-century Germans which the author includes in his Face of Our Time represent only a small selection drawn from August Sander’s major work, which he began in 1910 and which he has spent twenty years producing and adding fresh nuances to. The author has not approached this immense self-imposed task from an academic standpoint, nor with scientific aids, and has received advice neither from racial theorists nor from social researchers. He has approached his task as a photographer from his own immediate observations of human nature and human appearances, of the human environment, and with an infallible instinct for what is genuine and essential.

Conceptual:

The book is not ‘faces’ of our time, but ‘face’, singular. Suggesting that collectively, these people make one. It could be suggested that Sander’s concept was to unite these people as one collective representation of his time. There is no theory behind the work, just a look at the this period of time, on the face of it.

Another analysis layout: