How is sexuality and gender identity explored and represented in photography?

‘This binarism, which is but one of a series that underpins much photography theory and criticism, characterizes – in a manner that appears virtually self-evident – two possible positions for the photographer. The insider position – in this particular context, the “good” position – is thus understood to imply a position of engagement, participation, and privileged knowledge, whereas the second, the outsider’s position is taken to produce an alienated and voyeuristic relationship that heightens the distance between subject and object.’

(Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Inside/Out, 1995)

Introduction

Exploring sexuality and gender identity within photographs are usually captured and addressed from an outsider perspective, a viewpoint that is commonly objectifying and misleading. Instead, this intimate proximity, seen through Nan Goldin’s insider delineation of her close community, enables her to portray an extremely personal, and at times, voyeuristic perspective of her lived experiences. This narrative showcases a tableaux and uncompromising representation of Goldin’s and her found family’s feelings and familiarity within the queer community. Being in the same artistic circle as other photographers who predominantly photographed on film New York’s queer subculture, Goldin dedicated these portraits to preserving and capturing the essence of relationships, sexuality, gender exploration, and addiction during the 1970s and 1980s. As photography serves as an archive, there are many photographs exploring sexuality and gender identity which are immortalised, especially within the 19th and 20th century as photography began to become a popular and accessible medium of art and documentation. Situated within the fluidity and ambiguous notion of sexuality during these important and representative eras, these relaxed and fluid forms of identity captured within art and photography avoids distinct labelling, imposing a flexible identity of the individual.

Historical and theoretical context

Representation within art, photography and visual culture is to accept responsibility for the portrayal of the subject, and to deepen the understanding of the shared adjacent bond between the subject and the artist or photographer. The dichotomy between a subject’s essence being captured by someone outside their own community compared to inside their community showcases the epitome of “good” and “bad” representation of that person or group.

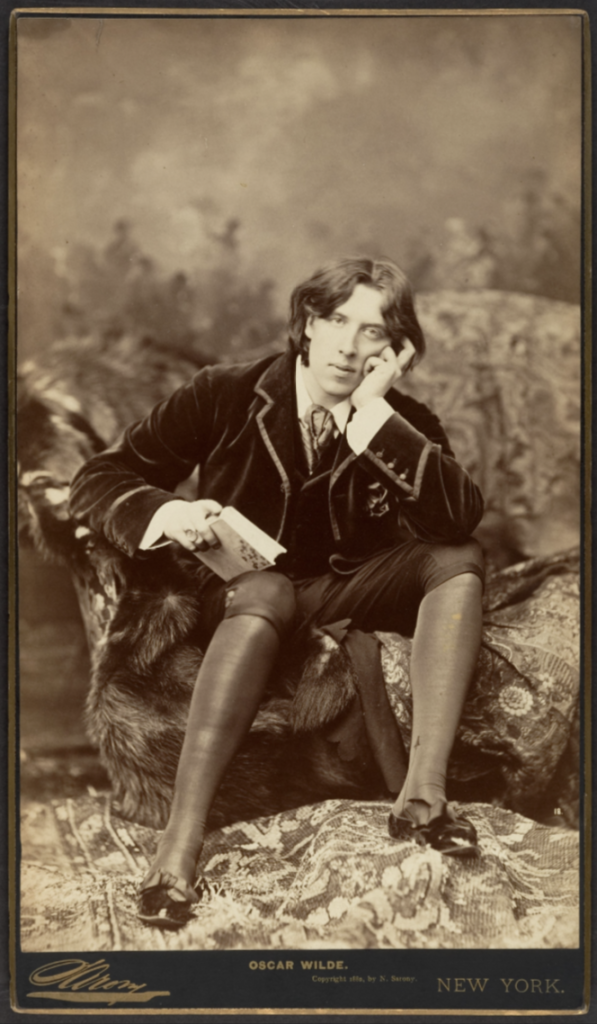

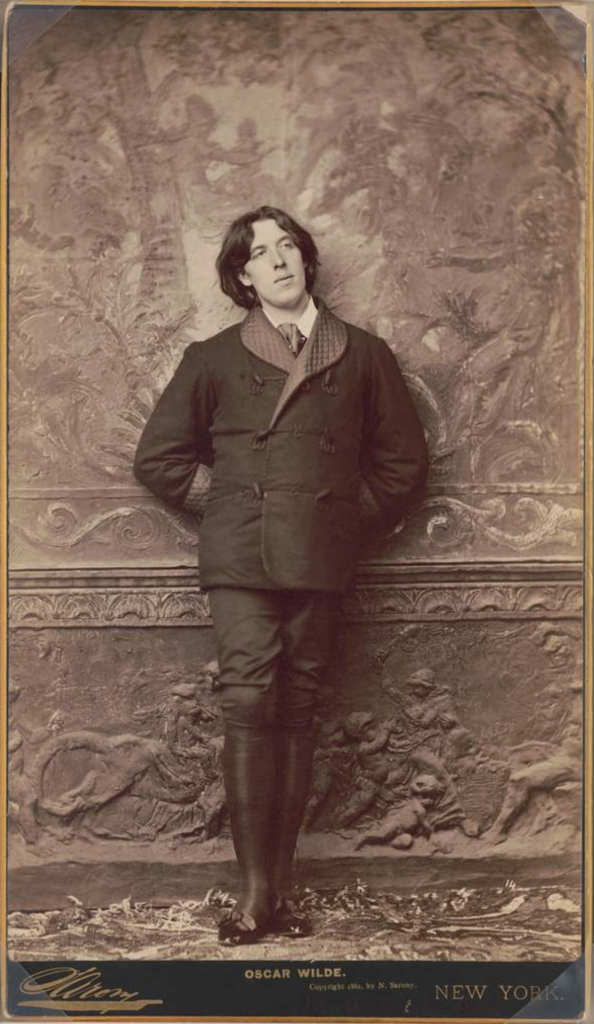

In circa 1882, the photographer Napoleon Sarony photographed portraits of Oscar Wilde, a poet and playwright in Victorian London, which positioned Wilde in the frame with his usual flamboyant and dandy personality, characteristics of the art movement of aestheticism which valued appearance of art over functions. The society of this time explicitly expressed disdain against sexual debauchery, which included the outlawing of all homosexual acts for ‘gross indecency’ under the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act, which Wilde was one of the first and highest importance figures prosecuted and put on trial for. This opens the discussion whether photography not only serves as an art form, but also archival material and an account of history.

Fig. 1 – Napoleon Sarony, Oscar Wilde, 1882

Fig. 2 – Napoleon Sarony, Oscar Wilde, 1882

In Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s ‘Inside/Out’, she highlights and contrasts whether a photograph appears as an insider or outsider perspective. She states, ‘Are the terms of reception- or, for that matter, presentation- in any way determined by the position- inside or out- of the photographer making the exposure? … for not only are the photographs themselves exterior views, but they model themselves directly on the impersonality, anonymity, and banality of the purely instrumental image.’ (Solomon-Godeau, Inside/Out, 1995) This solidifies Napoleon Sarony’s portraits of Oscar Wilde as solely photographed originating from an outsider’s perspective.

Nan Goldin

The photographer beholding a position of intimate proximity is vastly evident throughout Nan Goldin’s wide photography portfolio. Goldin was born 12th September, 1953 in Washington, D.C. and has relished in photography since she was fifteen, and in downtown Boston until she was nineteen. Ultimately driven by her need to remember herself and those she loves, Goldin solidified her innate passion of documenting scenes of her subcultural communities she made a home within for herself once moving from Boston to New York in 1978.

‘[Journalists] talk about the work I did on drag queens and prostitution, on “marginalised” people. We were never marginalised. We were the world. We were our own world, and we could have cared less about what “straight” people thought of us.’ (Goldin, 1986)

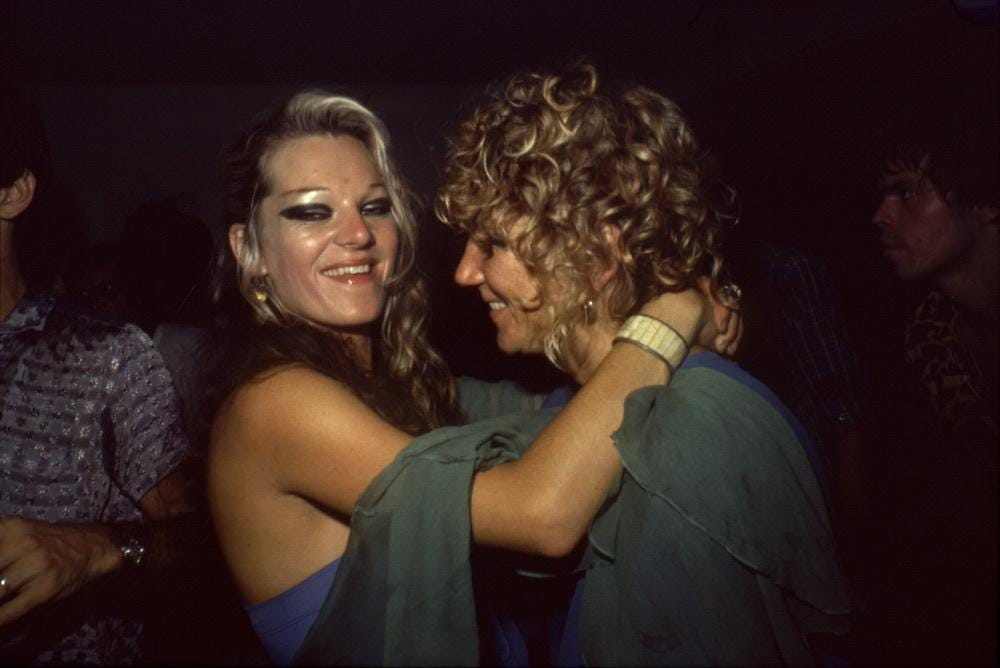

Utilising a narrative within photographs which conveys a deeply personal bond between Goldin and her subjects, she is often notably recognised for this inner representation of the communities and subcultures she shares space with. In her book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, she initially shared the photographs within with those photographed in frequently visited clubs and venues, and an immediate reaction from these peers contributed to its growth and ultimately its final presentation. ‘I look at Ballad and see the dynamics of both love and hate, tenderness and violence, as well as all kinds of ambivalence in relationships.’ (Goldin, 2012) Whether her subjects were portrayed in these harshly juxtaposing settings; an extremely domestic house or party setting, or at the funeral of her close friend, in a deadpan approach, Goldin addressed her subjects by their first name and most commonly added context on what was happening within the photograph, allowing the viewer to look inside the scene and realise much more of the situation and the lives of these people. Goldin personally engages her subjects with the creation of her art, and although this could have swayed the reception, especially the involvement of queer people from the 1970s, 80s and 90s, she does not leave this up for discussion. Her subjects are presented as the artwork, identifying visceral and ambivalent reactions towards her work and deepening the sense of these photographs being deemed as a voyeuristic gaze.

Fig. 3 – Nan Goldin, Cookie and Sharon Dancing at the Back Room, 1976

Fig. 4 – Nan Goldin, Warren and Jerry fighting, 1978

‘People in the pictures say my camera is as much a part of being with me as any other aspect of knowing me. It’s as if my hand were a camera. If it were possible, I’d want no mechanism between me and the moment of photographing. The camera is as much a part of my everyday life as talking or eating or sex. The instant of photographing, instead of creating distance, is a moment of clarity and emotional connection for me. There is a popular notion that the photographer is by nature a voyeur; the last one invited to the party. But I’m not crashing; this is my party. This is my family, my history’ (Goldin, 1986)

In Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s ‘Inside/Out’, she highlights and contrasts the representation of a photograph and how it shifts from being an insider or outsider portrayal of an individual, group, or community. She states, ‘The Ballad of Sexual Dependency can be considered as exemplary of the insider position … by way of examining the terms by which insiderness comes into play, the viewer can readily assume from the content of the images that the photographer is in a position of intimate proximity with her subjects. This is suggested by the depiction of the conventionally private activities of dressing and undressing, bathing, putting on makeup, the apparent physical closeness of the camera itself to its subjects in many of the pictures, and lastly, toward the end of the book, three images of one of the transvestites and a lover in bed together.’ (Solomon-Godeau, Inside/Out, 1995) This interpretation of Goldin’s work highlights the shared bond between herself and the subject of each individual photograph presented, and furthermore how these photographs involving vastly personal and intimate moments within the subject’s life would not have been documented without Goldin and her innate passion to document her community. This identifies how important an insider perspective is to accurately portray the life of an individual, and how aspects can be missed, hidden, or left out; whether purposely or not.

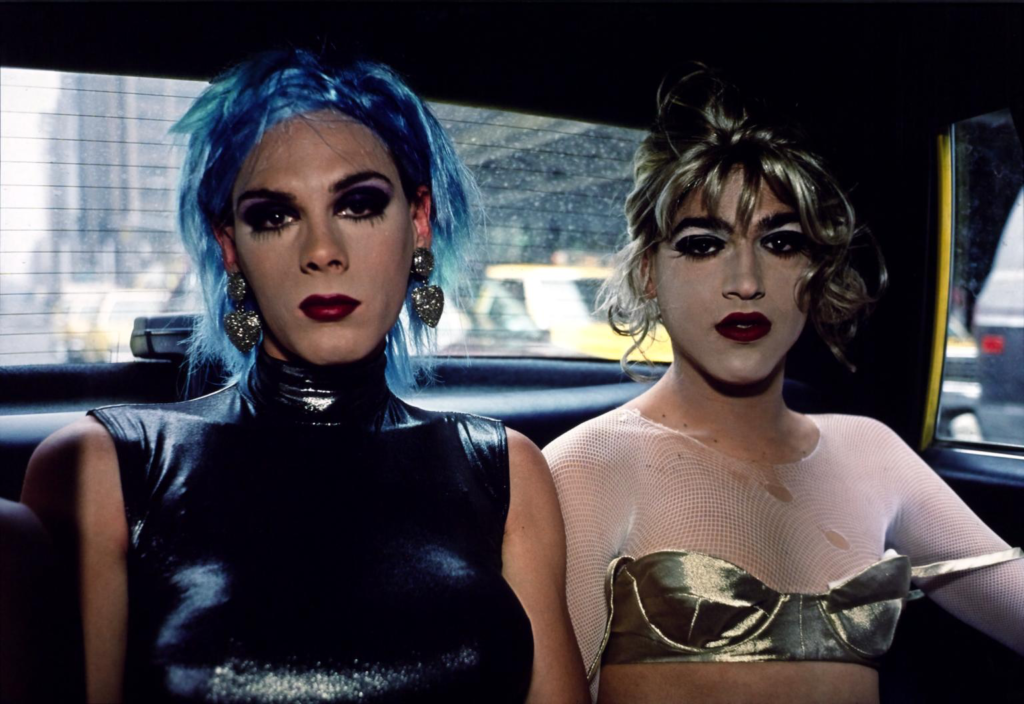

Fig. 5 – Nan Goldin, Misty and Jimmy Paulette in a taxi, 1991

Fig. 6 – Nan Goldin, Jimmy Paulette and Taboo! in the bathroom, 1991

Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency features a wide plethora of subjects she acknowledges holding an emotional and romantic investment for, and the photographs within this reflect this insider perspective of the queer community captured in a passionately close way by Goldin. As Nan Goldin has stated, ‘As children, we’re programmed into the limitations of gender distinction … But as we grow older, there’s a self-awareness that sees gender as a decision, as something malleable … Rather than accept gender distinction, the point is to redefine it … there is the decision to live out the alternatives, even to change one’s sex, which to me is the ultimate act of autonomy.’ (Goldin, 1986) In figures 5 and 6, Goldin has provided an insider representation of the queer community, a recurring subject in these two photos is Jimmy Paulette, who is depicted in a taxi with Misty, and then confidingly sharing the space in a bathroom with Taboo. Goldin’s photographs are usually personally close to the subjects and properly engage with the scene at hand, displaying the deeply held connection between the subject and photographer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the representation of sexuality and gender identity within photography and visual culture ultimately depends on who is photographing the subjects, and how that individual personally wishes to portray a group or community. An insider delineation of people inside of a community, which is captured throughout Nan Goldin’s work opens up the possibility of an extremely intimate and personal perspective of her and her found family’s lived experiences and familiarity within the queer community. The essence of these connections and relationships inside communities throughout history are intricately preserved through photographers and artists like Nan Goldin, and the many photographs exploring sexuality and gender identity have been immortalised since the 19th century with the popularisation of photography not only as an art medium, but also a documentation of history.

Bibliography

Sontag, S. (1977) ‘In Plato’s cave’ in On Photography. London: Penguin Books.

Goldin, Nan (1985) ‘The Ballad of Sexual Dependency’

Wikipedia, ‘Nan Goldin’

Solomon-Godeau, A. (1994), ‘Inside/ Out’ in Photography At The Dock: Essays on Photographic History, Institutions, and Practices. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

PhotoPedagogy, ‘Inside/Out: Thinking about the ethics of photography’

Bull, S. (2009), ‘Snapshots’ in Photography. London: Routledge.

Zuromski, C. (2009) . ‘On Snapshot Photography: Rethinking Photographic Powers in Public and Private Spheres’ in J.J. Long, Andrea Noble, Edward Welch, Photography: Theoretical Snapshots. London: Routledge.

Kotz, L. (1998) ‘”Aesthetics” of Intimacy’ in Bright, D. (1998) The Passionate Camera: Photography and bodies of desire. London: Routledge