Once upon a time….

A well rehearsed phrase that we are all familiar with, invoking childhood memories of fairytales, grandparents recounting old days or stories around the campfire. American novelist Kurt Vonnegut argued that the quality that defined good storytellers was simply that they themselves loved stories.

In this module we will study how different narrative structures can be used to tell stories in pictures from looking at photography, cinema and literature in photo-essays, film and books. We will consider narrative within a documentary approach where observation is key in representing reality, albeit we will look at both visual styles within traditional photojournalism as well as contemporary photography which employs a more poetic visual language that straddles the borders between objectivity and subjectivity, fact and fiction.

In order to understand how photography as a medium can be applied to tell a story we need to understand the differences between narrative and story and how editing, sequencing and design is intrinsic to this process.

THEORY

Often people tend to think of narrative and story as the same thing. In photography that is no exception. Jörg M. Colberg, a photographer, teacher and editor of Conscientious Photo Magazine (online blog dedicated to contemporary fine-art photography) has written extensively about narrative in photography. For you to gain a better understanding of the differences between narrative and story when we think about it in relation to making a photobook (which is your main outcome in your Personal Study later in the academic year) or in your current task of making a photo-zine you NEED TO READ his two blog posts; Photography and Narrative (part 1) and Photography and Narrative (part 2).

According to Dictionary.com, narrative can be:

- a story or account of events, experiences, or the like, whether true or fictitious

- a book, literary work, etc., containing such a story, or

- the art, technique, or process of narrating, or of telling a story.”

In Colberg’s view;

‘Those three options really aren’t the same at all. A photobook’s story is not the same as the book itself…. What I tend to find is that many photographers use the term narrative in the sense of it being the same as story (option 1), but what they mean is that it is the way the story is told (Option 3).’

He continues:

‘This is because it will contain a set of photographs that are being presented in a very specific way: there is an edit, a sequence, and very specific decisions about design and production were (hopefully) being made. As I’m trying to explain in the following, the edit and sequence (and to a lesser extent design and production) form a specific narrative that, in turn, might or might not produce or allude to a story. How to approach this then?’

When Colin Pantall made his book, All Quiet on the Homefront about his daughter growing up and becoming a father he wrote about the process of making it on his Blog here: Identifying the Story: Sequencing isn’t narrative

In Pantall’s experience narrative isn’t just sequencing a set images that flows together nicely. He says:

‘In photobooks there are so many elements used in editing, sequencing and creating a narrative. It’s really difficult. For All Quiet on the Home Front, we went through the lot of them. Sequencing by chronology, geography, family, resemblance, art history, season, colour, form, tone, flora, expression, dress, climate, mood, symbolism, material, and so on. The sequencing was a gradual process that was embedded into the editing with voice, mode, person, text, the basic best picture edit and much more besides.’

In his view identifying the story first and being able to communicate it in three words is essential.

‘You can sequence in a multitude of ways in other words. But none of that made a narrative. What made the narrative was actually identifying what the story was about. Do that and then you can create all the structures through which the story can flow – and that, structures plus story, creates the narrative.’

For photographer, writer and lecturer, Lewis Bush; ‘narrative are things that exists within stories.’ In his article, Storytelling: A Poverty of Theory, Bush gives different reasons why photography as a medium does not have an established theory on narrative like cinema or literature. He also wonders why photographers often refer to themselves as storytellers but have little understanding of the differences between story and narrative when applied to photography.

‘One story can spawn many narratives, a fact that, in contrast to photography, is well understood in literature and cinema….when I say ‘I’m going to tell you a story’ I actually tell you a narrative of that story.’

Bush cites an example in cinema, Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon where multiple narratives are presented on screen of a murder, that may or may not have happened.

In photography today Bush reminds us;

‘it is well understand that single images are not reality, they are a representation of it.’ Similarly, a series of images put together in a fragmentary and incomplete order is ‘a record of something [that] are always a narrative of a story or event, never a full reflection of the thing itself’.

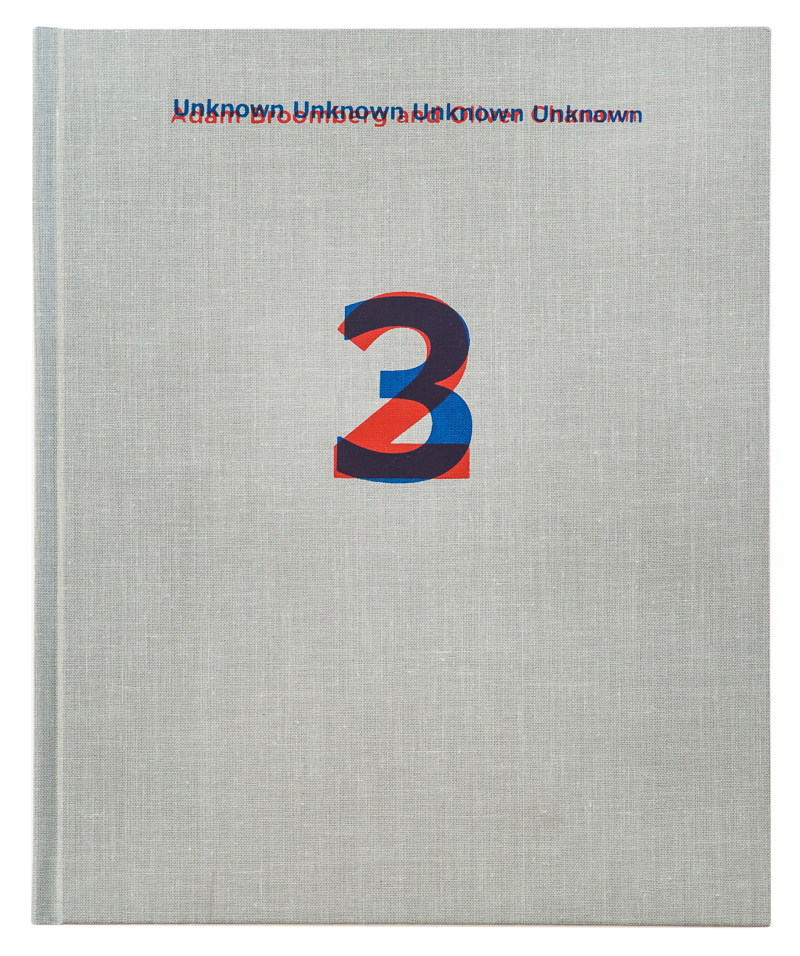

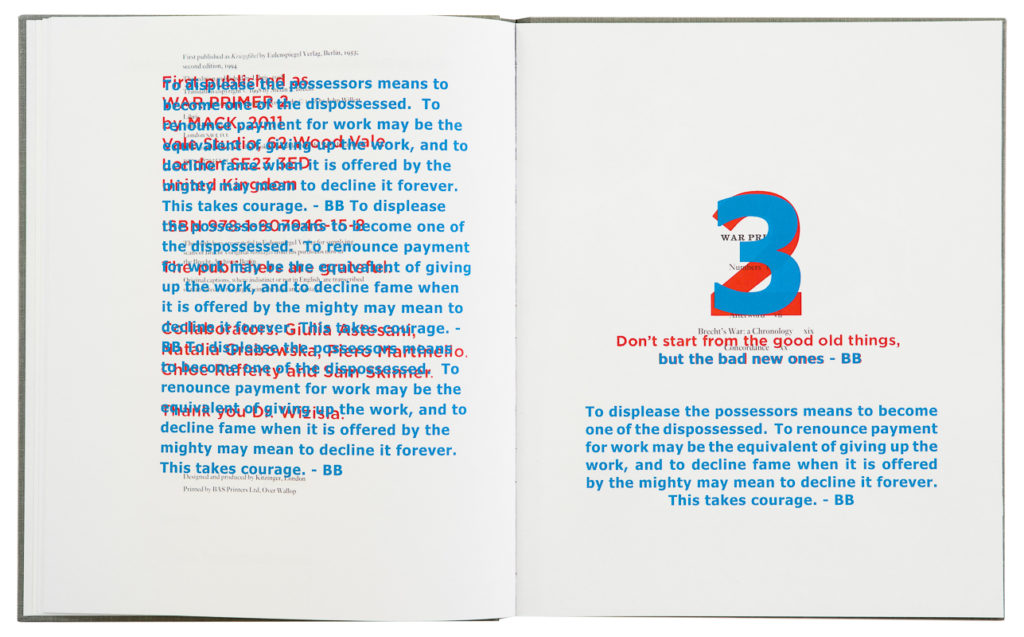

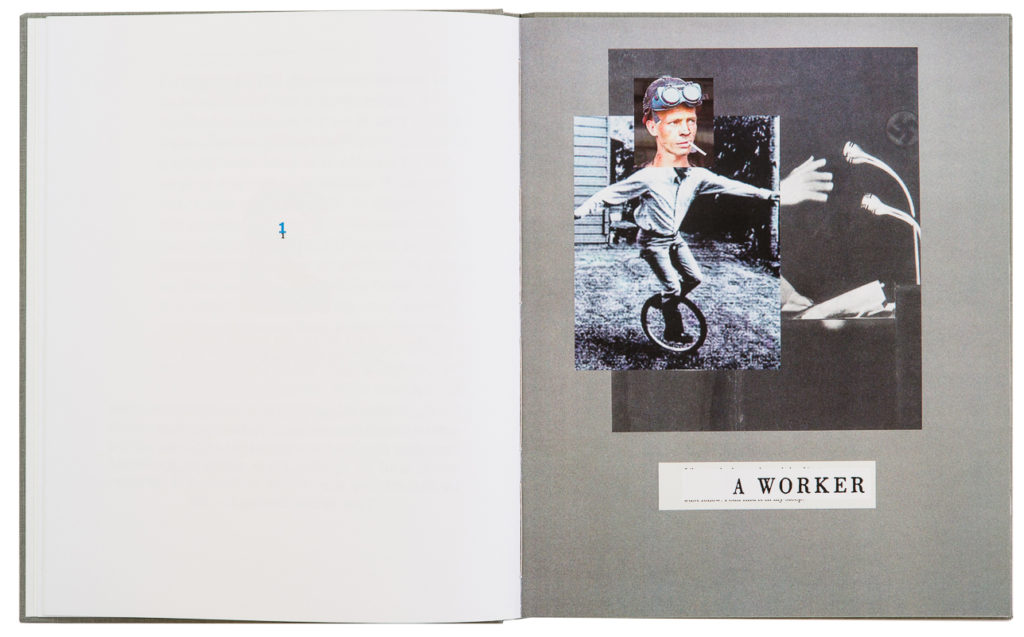

Lewis Bush gives examples of books that he has made which provides different narrative structure, from very linear to experimental. For example: Books that rework the narratives of other books, books which can be read back to front and front to back, and books with no fixed narrative at all. I’m currently working on one with a narrative which travels forwards and backwards in time simultaneously, and another a book which will not actually exist, and so I suppose neither will its narrative.

In a follow article: ‘Photographic Narrative: Between Cinema and Novel‘ Lewis Bush cites different examples from both cinema, literature and photography and identity each mediums different strengths and weaknesses.

In Bush’s view, photography’s narrative strength is;

‘It’s sheer power of description.’ A single photograph can depict a scene with a verisimilitude which pages of written account would still fail to capture. It is this quality which led photography to be first employed for practices like crime scene photography, in place of the unreliable memory and incomplete notes that had previously been relied upon.

Conversely photography also has many weaknesses, such as explaining things. Bush cites German theatre parctitioner and playwright Bertol Brecht who wrote, a photograph of a factory tells us what a factory looks like, but it tells us very little about the relationships that underlie it.

Bush also references Roland Barthes , whose seminal book, Camera Lucida,(1980) is a bedrock of photographic theory, especially, the relationship between photography and memory, photograph and death. He describes reading a sentences where Barthes, ‘characterised photographs as things which were somewhere “between cinema and novel”.

Bush then outlines traits and similarities for storytelling between photography and cinema, photography and literature and provides a number of examples which we will have a closer look at below.

CINEMA

Chris Marker: La Jétte

Chris Marker, (1921-2012) was a French filmmaker, poet, novelist, photographer, editor and multi-media artist who has been challenging moviegoers, philosophers, and himself for years with his complex queries about time, memory, and the rapid advancement of life on this planet. Marker’s La Jetée is one of the most influential, radical science-fiction films ever made, a tale of time travel. What makes the film interesting for the purposes of this discussion, is that while in editing terms it uses the language of cinema to construct its narrative effect, it is composed entirely of still images showing images from the featureless dark of the underground caverns of future Paris, to the intensely detailed views across the ruined city, and the juxtaposition of destroyed buildings with the spire of the Eiffel Tower. You can read more here about the meaning of the film and it is available on Vimeo here in its entirety (29 mins)

Mark Cousins: Atomic, Living in Dread and Promise

A narrative can also be made constructed entirely of archive footage as in Atomic, Living in Dread and Promise, a film that shows impressionistic kaleidoscope of our nuclear times – protest marches, Cold War sabre-rattling, Chernobyl and Fukishima – but also the sublime beauty of the atomic world, and how x-rays and MRI scans have improved human lives. The nuclear age has been a nightmare, but dreamlike too. Made by director and film critic, Mark Cousins and featuring original music score by Mogwai, it was first broadcast on BBC4 as part of Storyville documentary. Your can read a Q&A with Cousins’ here where he discusses the making of the film.

Christopher Nolan: Memento

Memento is a 2000 American neo-noir psychological thriller film written and directed by Christopher Nolan. Guy Pearce stars as a man who, as a result of an injury, has anterograde amnesia (the inability to form new memories) and has short-term memory loss approximately every fifteen minutes. He is searching for the people who attacked him and killed his wife, using an intricate system of Polaroid photographs and tattoos to track information he cannot remember.

The film is presented as two different sequences of scenes interspersed during the film: a series in black-and-white that is shown chronologically, and a series of color sequences shown in reverse order (simulating for the audience the mental state of the protagonist). The two sequences meet at the end of the film, producing one complete and cohesive narrative

Telling a story in reverse can be an interesting way to construct a narrative. Both cinema and literature are good at jumping between different time modes, past, present and future. Moving image and sound can enhance these different temporal shifts and written language is good and transporting your imagination from one time zone to another. Photography is mute but different strategies can be employed such as changing from colour to monochrome suggesting a different time or a different set of images. Using old photographs from archives, or found imagery can add complexity too, and including words can support a sequence of images, or add tension between the visual and the textual adding other elements to a photographic narrative.

Memento: Narrative and Postmodernism is also being looked at in Media Studies and if you are studying this subject make sure you include knowledge and understanding learned. Adopting a inter-disciplinary approach to your work is advantageous and being able to use theory and/ or context from other subjects will add value to your overall quality of your work and potentially achieve higher marks.

Theorists like Sergei Eisenstein, D.W Griffiths, Lev Kuleshov, Jean Epstein, John Grierson (also the coiner of the term ‘documentary’), Dziga Vertov, Andre Bazin, and Siegfried Kracauer went into sometimes painful detail to articulate theories about how various film and editing combinations created different forms of meaning. Many of these ideas remain surprisingly robust and useful a century later, and remain the bedrock of much of the theory taught to film students. Let’s look at some narrative structures and film editing techniques that are used in cinema.

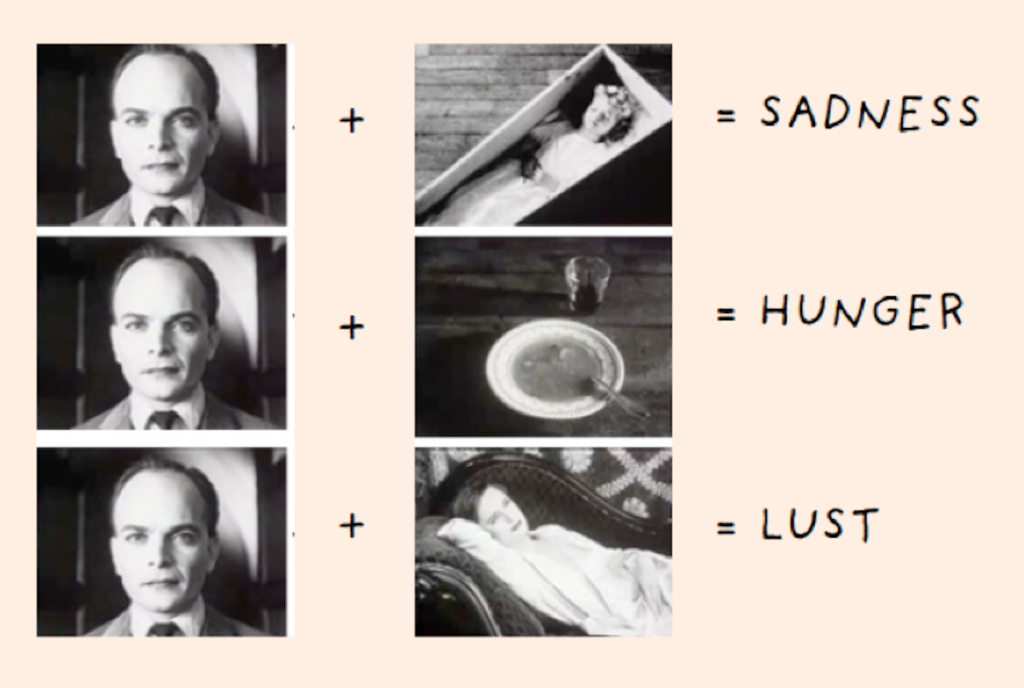

The Kuleshov effect is a film editing (montage) effect demonstrated by Soviet filmmaker Lev Kuleshov in the 1910s and 1920s. It is a mental phenomenon by which viewers derive more meaning from the interaction of two sequential shots than from a single shot in isolation. Through this phenomenon we can suggest meaning and manipulate space, as well as time.

Kuleshov edited a short film in which a shot of the expressionless face of Tsarist matinee idol Ivan Mosjoukine was alternated with various other shots (a bowl of soup, a girl in a coffin, a woman on a divan). The film was shown to an audience who believed that the expression on Mosjoukine’s face was different each time he appeared, depending on whether he was “looking at” the bowl of soup, the girl in the coffin, or the woman on the divan, showing an expression of hunger, grief, or desire, respectively. The footage of Mosjoukine was actually the same shot each time.

Kuleshov used the experiment to indicate the usefulness and effectiveness of film editing. The implication is that viewers brought their own emotional reactions to this sequence of images, and then moreover attributed those reactions to the actor, investing his impassive face with their own feelings. Kuleshov believed this, along with montage, had to be the basis of cinema as an independent art form.

For more details see Dr McKinlay’s blog on Narrative in Cinema and The Language of Moving Image which look more specifically at some of the conventions and key terminology associated with moving image (film, TV, adverts, animations, installations and other moving image products.)

PHOTOGRAPHY

Let’s explore some examples of images used in photo-essays and photobooks and see if we can identify the story as well as examine how narrative is constructed through careful editing, sequencing and design.

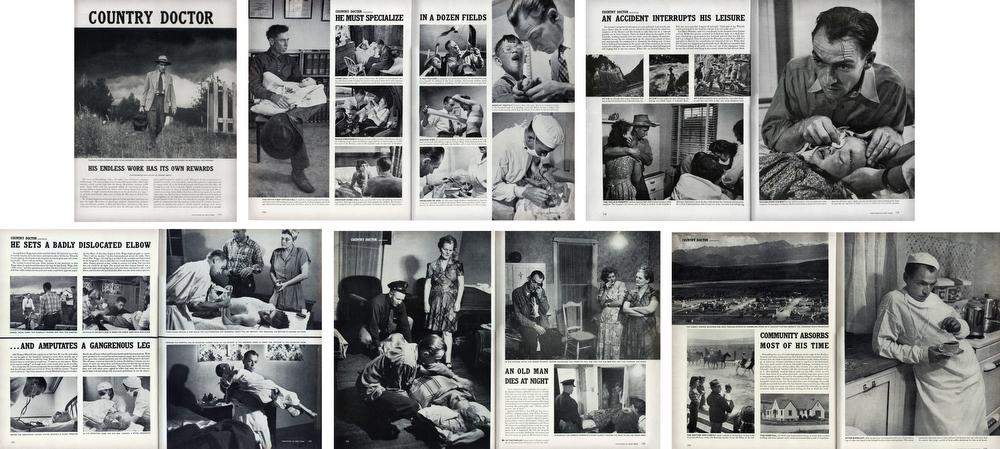

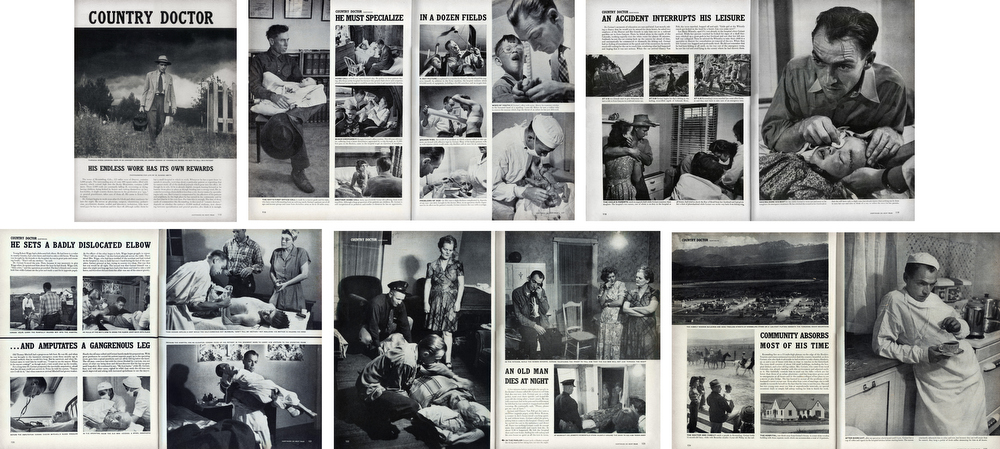

W. Eugene Smith: Country Doctor

PHOTO-ESSAY: The life of a country doctor in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains

“A photo is a small voice, at best, but sometimes – just sometimes – one photograph or a group of them can lure our senses into awareness. Much depends upon the viewer; in some, photographs can summon enough emotion to be a catalyst to thought”

W. Eugne Smith

W. Eugene Smith compared his mode of working to that of a playwright; the powerful narrative structures of his photo essays set a new benchmark for the genre. His series, The Country Doctor, shot on assignment for Life Magazine in 1948, documents the everyday life of Dr Ernest Guy Ceriani, a GP tasked with providing 24-hour medical care to over 2,000 people in the small town of Kremmling, in the Rocky Mountains. The story was important at the time for drawing attention to the national shortage of country doctors and the impact of this on remote communities. Today the photoessay is widely regarded as representing a definitive moment in the history of photojournalism.

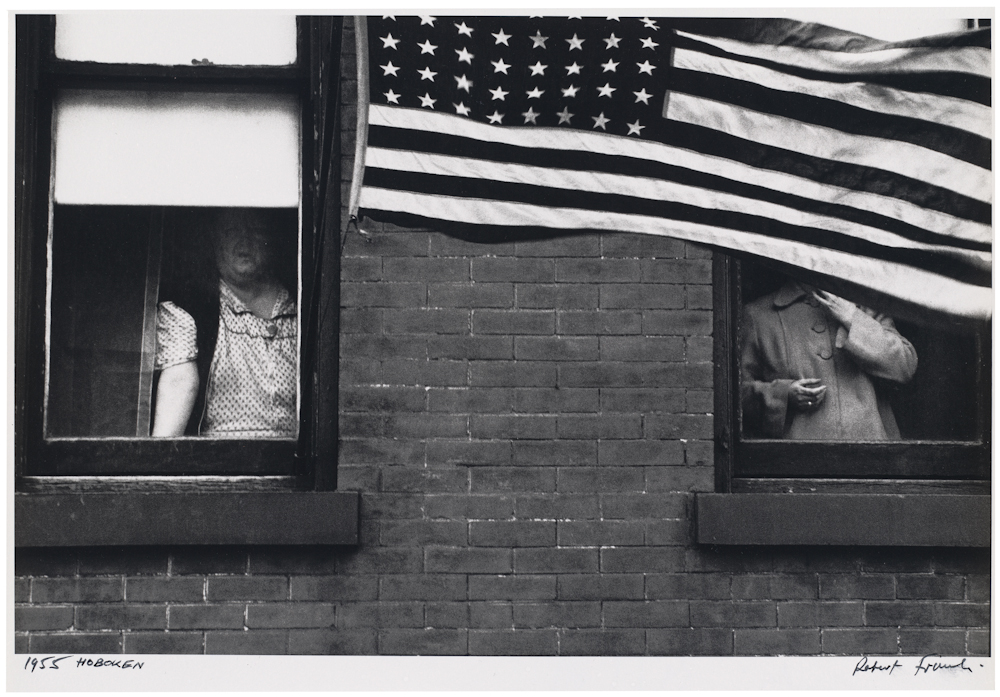

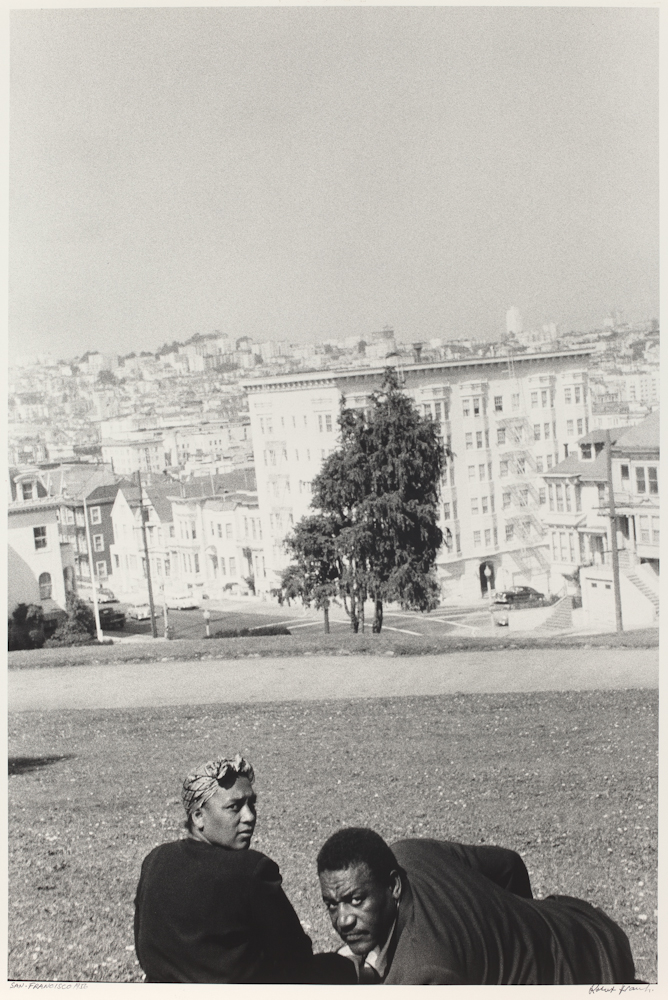

Robert Frank: The Americans

In October of 1958, French publisher Robert Delpire released Les Américains in Paris. The following year Grove Press published The Americans in New York with an introduction by American writer, Jack Kerouac (the book was released in January 1960).

Like Frank’s earlier books, the sequence of 83 pictures in The Americans is non-narrative and nonlinear; instead it uses thematic, formal, conceptual and linguistic devices to link the photographs. The Americans displays a deliberate structure, an emphatic narrator, and what Frank called a ‘distinct and intense order’ that amplified and tempered the individual pictures.

Although not immediately evident, The Americans is constructed in four sections. Each begins with a picture of an American flag and proceeds with a rhythm based on the interplay between motion and stasis, the presence and absence of people, observers and those being observed. The book as a whole explores the American people—black and white, military and civilian, urban and rural, poor and middle class—as they gather in drugstores and diners, meet on city streets, mourn at funerals, and congregate in and around cars. With piercing vision, poetic insight, and distinct photographic style, Frank reveals the politics, alienation, power, and injustice at play just beneath the surface of his adopted country.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/videos/category/arts-culture/inside-robert-franks-the-americans/

Since its original publication, The Americans has appeared in numerous editions and has been translated into several languages. The cropping of images has varied slightly over the years, but their order has remained intact, as have the titles and Kerouac’s introductory text. The book, fiercely debated in the first years following its release, has made an indelible mark on American culture and changed the course of 20th-century photography. Read article by Sean O’Hagan in The Guardian

Rita Puig Serra Costa: Where Mimosa Bloom

Dealing with the grief that the photographer suffered following the death of her mother, Where Mimosa Bloom by Rita Puig Serra Costatakes the form of an extended farewell letter; with photography skillfully used to present a visual eulogy or panegyric. This grief memoir about the loss of her mother is part meditative photo essay, part family biography and part personal message to her mother. These elements combine to form a fascinating and intriguing discourse on love, loss and sorrow.

“Where Mimosa Bloom” is the result of over two years work spent collecting and curating materials and taking photographs of places, objects and people that played a significant role in her relationship to her mother. Rita Puig Serra Costa skillfully avoids the dangerous lure of grief’s self-pity, isolationism, world-scorn and vanity. The resonance of “Where Mimosa Bloom” comes from all it doesn’t say, as well as all that it does; from the depth of love we infer from the desert of grief. Despite E.M.Forster’s words – “One death may explain itself, but it throws no light upon another” – Rita Puig Serra Costa proves that some aspects of grief are universal, or can be made so through the honesty and precision with which they are articulated.

Yoshikatsu Fujii: Red Strings

I received a text message. “Today, our divorce was finalized.” The message from my mother was written simply, even though she usually sends me messages with many pictures and symbols. I remember that I didn’t feel any particular emotion, except that the time had come. Because my parents continued to live apart in the same house for a long time, their relationship gently came to an end over the years. It was no wonder that a draft blowing between the two could completely break the family at any time.

In Japan, legend has it that a man and woman who are predestined to meet have been tied at the little finger by an invisible red string since the time they were born. Unfortunately, the red string tying my parents undone, broke, or perhaps was never even tied to begin with. But if the two had never met, I would never have been born into this world. If anything, you might say that there is an unbreakable red string of fate between parent and child.

Before long, I found myself thinking about the relationship between my parents and . How many days could I see my parents living far away? What if I couldn’t see them anymore? Since I couldn’t help feeling extremely anxious about it, I was driven to visit my parents’ house many times. Every day I engage in awkward conversation with my parents, as if in a scene in their daily lives. I adapt myself to them, and they shift their attitude toward me. We do not give way entirely to the other side, but rather meet halfway. Indeed family problems remain unresolved, although sometimes we tell allegorical stories and share feelings. It means a lot to us that our perspectives have changed with communication.

My family will probably never be all together again. But I feel without a doubt that there is proof inside of each of us that we once lived together. To ensure that the red string that ties my family together does not come undone, I want to reel it in and tie it tight.

NARRATIVE – a summary

Narrative is essentially the way a story is told. For example you can tell different narratives of the same story. It is a very subjective process and there is no right or wrong. Whether or not your photographic story is any good is another matter.

An analogy: if you witnessed a road accident and the police arrived to take statements from witnesses. Your version of events would be different to that of other witnesses or bystanders. They are both ‘true’ to what you saw and they both tell a different narrative depending on where you were in relation to the event, your point of view and how you remembered the event as it happened.

Narrative is constructed when you begin to create relationships between images (and/or text) and present more than two images together. Your selection of images (editing) and the order of how these images appear on the pages (sequencing) contributes significantly to the construction of the narrative. So too, does the structure and design of the photo-zine or photobook.

However, it is essential that you identity what your story is first before considering how you wish to tell it. Planning and research are also essential to understanding your subject and there are steps you can take in order to make it successful. Once you have considered the points made between the differences in narrative and story, write the following:

PLANNING: Write a specification that provide an interpretation and plan of how you intend to explore A Love Story. This must include at least 3 photoshoots you will be doing in the next 2-3 weeks (these could include photo-assignments). How do you want your images to look and feel like? Include visual references to artists/photographers in terms of style, approach, intentions, aesthetics concept and outcome. Remember the final outcome is a 16 page photo-zine so you will need to edit a final series of 12-16 images that sequenced together as a set forms a narrative that visualises your love story.

STORY: What is your love story?

Describe in:

- 3 words

- A sentence

- A paragraph

NARRATIVE: How will you tell your story?

- Images > new photographic responses, photo-shoots

- Archives > old photos from family albums, iPhone

- Texts > letters, documents, poems, text messages

AUDIENCE: Who is it for?

Most image makers tend to overlook the experience of the viewer. Considering who your audience is and how they may engage with your photo-zine is important factor when you are designing/ making it.

- Reflect and comment on this in your specification (age group, demographic, social/ cultural background etc.)

PHOTOBOOKS

A few photo book dealing with memory, loss and love

Yury Toroptsov: Deleted Scene

On a mission to photograph the invisible, with Deleted Scene photographer Yury Toroptsov takes us to Eastern Siberia in a unique story of pursuit along intermingling lines that form a complex labyrinth. His introspective journey in search of a father gone too soon crosses that of Akira Kurosawa who, in 1974, came to visit and film that same place where lived the hunter Dersu Uzala.

Yury Toroptsov is not indifferent to the parallels between hunting and photography, which the common vocabulary makes clear. Archival documents, old photographs, views of the timeless taiga or of contemporary Siberia, fragments or deleted scenes are arranged here as elements of a narrative. They come as clues or pebbles dropped on the edge of an invisible path where the viewer is invited to lose himself and the hunter is encouraged to continue his relentless pursuit.

Mayumi Suzuki: The Restoration Will

My parents, who a owned photo studio, went missing after the 2011 tsunami. Our house was destroyed. It was a place for working, but also for living. I grew up there. After the disaster, I found my father’s lens, portfolio, and our family album buried in the mud and the rubble.

One day, I tried to take a landscape photo with my father’s muddy lens. The image came out dark and blurry, like a view of the deceased. Through taking it, I felt I could connect this world with that world. I felt like I could have a conversation with my parents, though in fact that is impossible.

The family snapshots I found were washed white, the images disappearing. The portraits taken by my father were stained, discolored. These scars are similar to the damage seen in my town, similar to my memories which I am slowly losing.

I hope to retain my memory and my family history through this book. By arranging these photos, I have attempted to reproduce it.

Dragana Jurisic’s YU: The Lost Country

Yugoslavia fell apart in 1991. With the disappearance of the country, at least one million five hundred thousand Yugoslavs vanished, like the citizens of Atlantis, into the realm of imaginary places and people. Today, in the countries that came into being after Yugoslavia’s disintegration, there is a total denial of the Yugoslav identity.

“There proceeds steadily from that place a stream of events which are a source of danger to me,” wrote the Anglo-Irish writer, Rebecca West in 1937. “That place” was Yugoslavia, the country in which I was born. Realizing that to know nothing of an area “which threatened her safety” was “a calamity”, she embarked on a journey through Yugoslavia. The result was Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. Initially intended as “a snap book” it spiraled into half a million words, a portrait not just of Yugoslavia, but also of Europe on the brink of the Second World War, and widely regarded as one of the masterpieces of the 20th century.

At Easter 2011, I started retracing Westʼs journey and re-interpreting her masterpiece by using photography and text, in attempt to re-live my experience of Yugoslavia and to re-examine the conflicting emotions and memories of the country that was.

Jacob Aue Sobol: Sabina

In 1999, Jacob Aue Sobol went to live in the settlement of Tiniteqilaaq, Greenland, where he lived the life of a fisherman and hunter with his Greenlandic girlfriend Sabine and her family. Taken over three years Sobol’s book records, in photographs and narratives, his encounter with Sabine and their life on the east coast.

Photographer Jacob Aue Sobol reflects on the three years he spent in Greenland and the traveling he did there. While his first trip was focused on documenting the culture, his second trip revolved around his girlfriend Sabine, who later became the subject of a series of photographs.

Laia Abril: The Epilogue’

‘The Epilogue’ is the book about the story of the Robinson family – and the aftermath suffered in losing their 26 year old daughter to bulimia. Working closely with the family Laia Abril reconstructs Cammy’s life telling her story through flashbacks – memories, testimonies, objects, letters, places and images. The Epilogue gives voice to the suffering of the family, the indirect victims of ‘eating disorders’, the unwilling eyewitnesses of a very painful degeneration. Laia Abril shows us the dilemmas and struggles confronted by many young girls; the problems families face in dealing with guilt and the grieving process; the frustration of close friends and the dark ghosts of this deadliest of illnesses; all blended together in the bittersweet act of remembering a loved one. Read more here on Laia Abril’s website

AUDIENCE: Most image makers tend to overlook the experience of the viewer. Considering who your audience is and how they may engage with your photo-zine is important factor when you are designing/ making it.

Students past responses to the theme of love, friendship, family etc.

Niah Da Costa: Espera

For my photo book, the main theme was intimacy and young love. I wanted to explore my relationship with my boyfriend and show a series of different styles of images. I called this photo book “Espera” which means to wait in Portuguese, as this word (besides love) is a word that both Jack and I use frequently. Read more on her BLOG here.

Amy Low: Nothing can get between us

A photo-book which is based on specific people in my life and what makes them an individual, I want this to also center around the theme of youth culture. Each picture/section of my book is about one person and their features/interests and things that make them who they are. I also plan to have pictures which break theme in the book to act as a barrier between each portrait. Read more on her BLOG here.

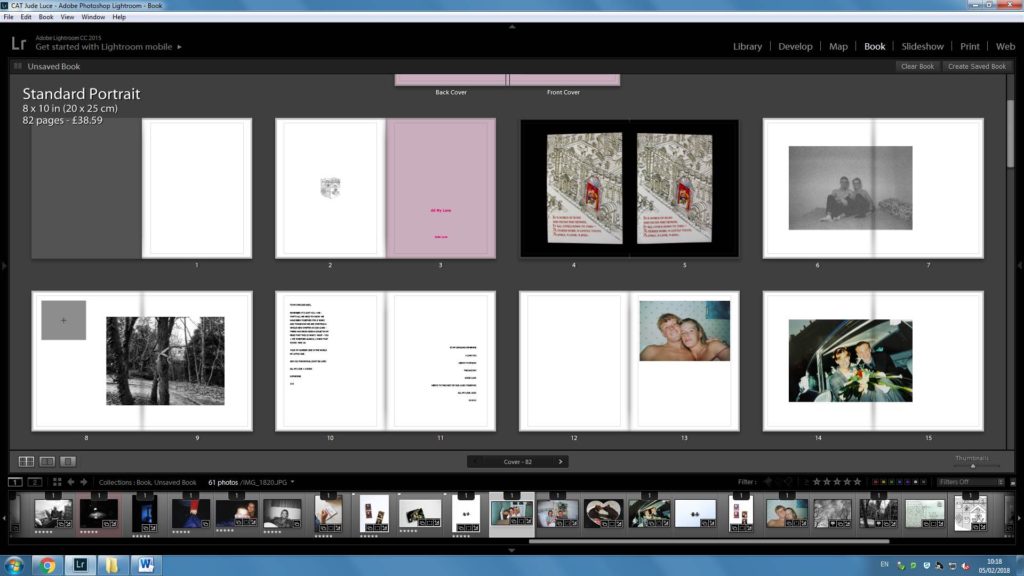

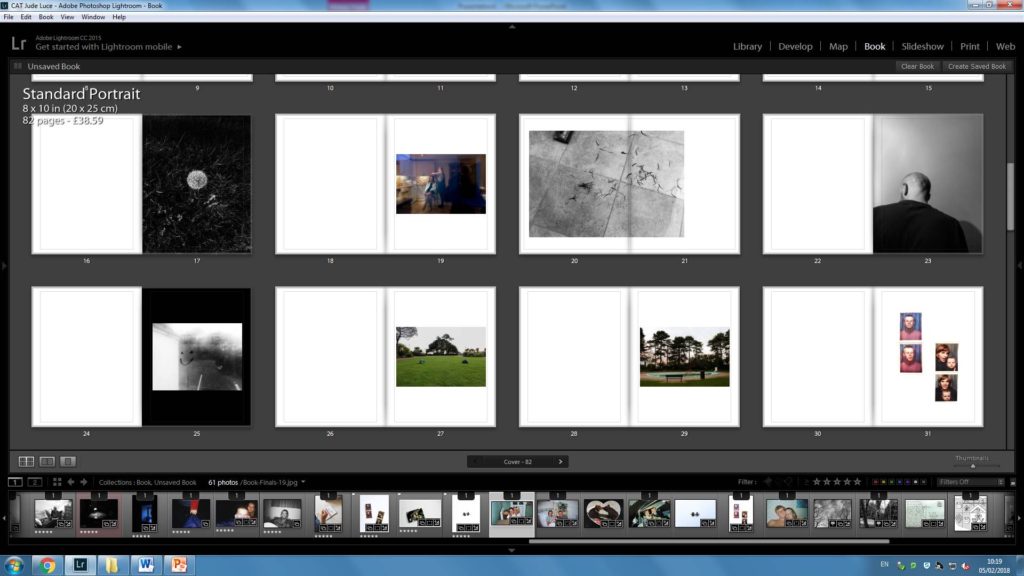

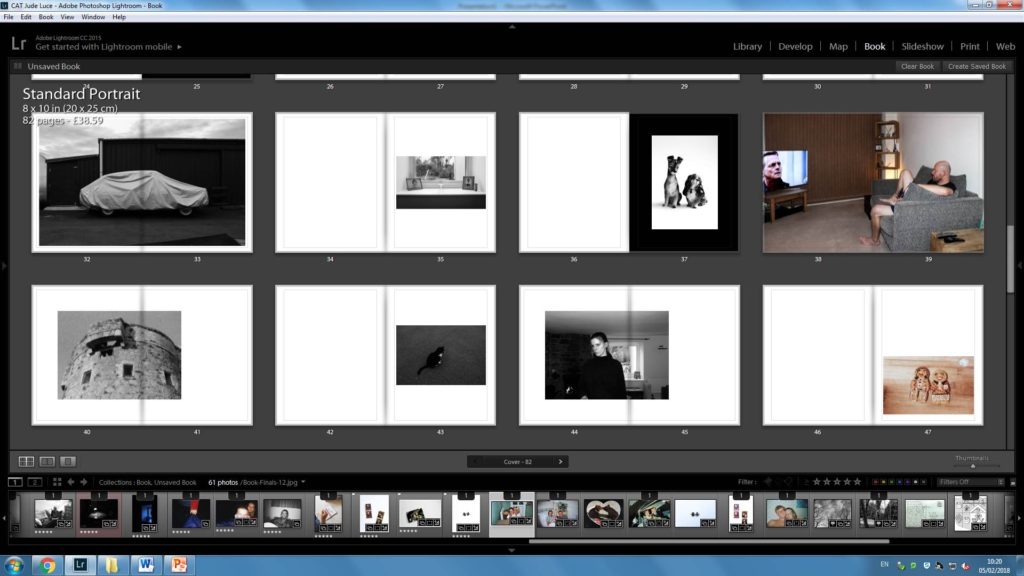

Jude Luce: All My Love

My plan for my photo book is to produce a detailed and insightful exploration into my family life, with me centered within the middle. This is the running theme throughout and I hope to show it through poetic, still images of landscapes or objects which may have no direct meaning at its face value but has a deeper meaning once inferred. As well, the portraits in my project are intended to be collaborative and intimate to show the relationships I hold with the people in my life but the portraits are intended to show the emotion of each being as well. I have contrasted yet shown the similarities of my mum and dad’s relationship when they were together to that of my relationship with Lucy now and the overall look I hope to achieve is that of a fun, vibrant, light-hearted but quite solemn and sombre image-based diary about how I am still developing through the events if life and the attachments I have built from the event which shaped my life – my mum and dad’s divorce. I want their to be an obvious existence of the theme of attachment but also an underlying theme of detachment. Although these themes are the main focus for my book, they are underlying themes which are subtly hinted at every now and then by a sequence which develops upon the understanding of love. Memory is fragile and I use this notion as a driving force for my project made up of diaristic photographs, which, when come together, create an album of moments in time which in-turn lend themselves to never be forgotten. I have attempted not to avoid the subject of my mum and dad’s divorce but felt it easier to express this and my feelings towards it through other subject matter, being my relationship with my girlfriend and the other people in my life, such as my individual relationships with my mum and dad and how I view them in solitary opposition to one another.

Read more on Jude’s BLOG

link to photobook, All My Love