“The Great Plains of North America exists for me both as a physical landscape and as an idea, or internal landscape” – Joe Deal

Joe Maurice Deal was an American landscape photographer, who became one of the ten founding photographers of specializing in depicting how the landscape of the earth had been transformed by people. Born in Topeka, Kansas on August 12, 1947, Deal attended the Kansas City Art Institute where he subsequently earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. After his graduation in 1970, Deal worked as a janitor and guard at at the George Eastman House in New York within its museum of photography instead of enrolling in the military. This led to him receiving his Masters degree in photography alongside his Masters of Fine Arts degree in the University of New Mexico, paving his way to becoming one of the participants in the movement of New Topographics.

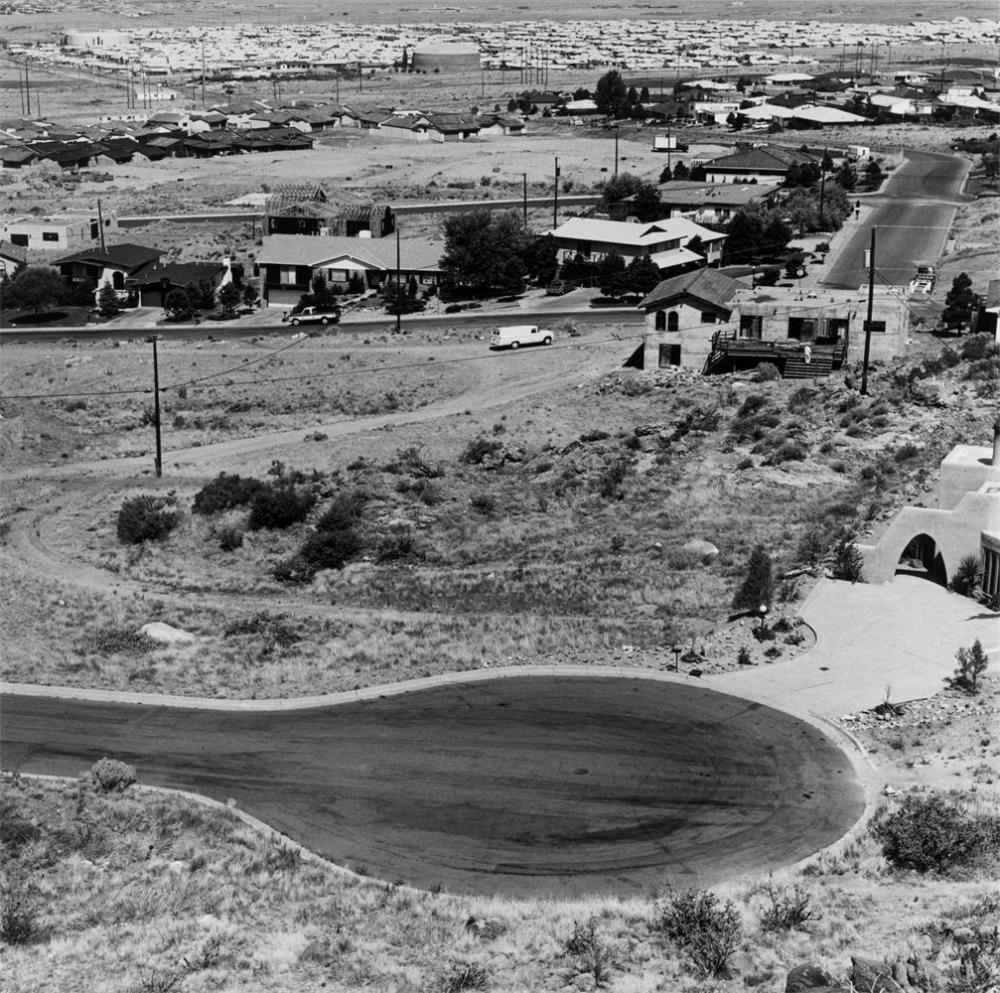

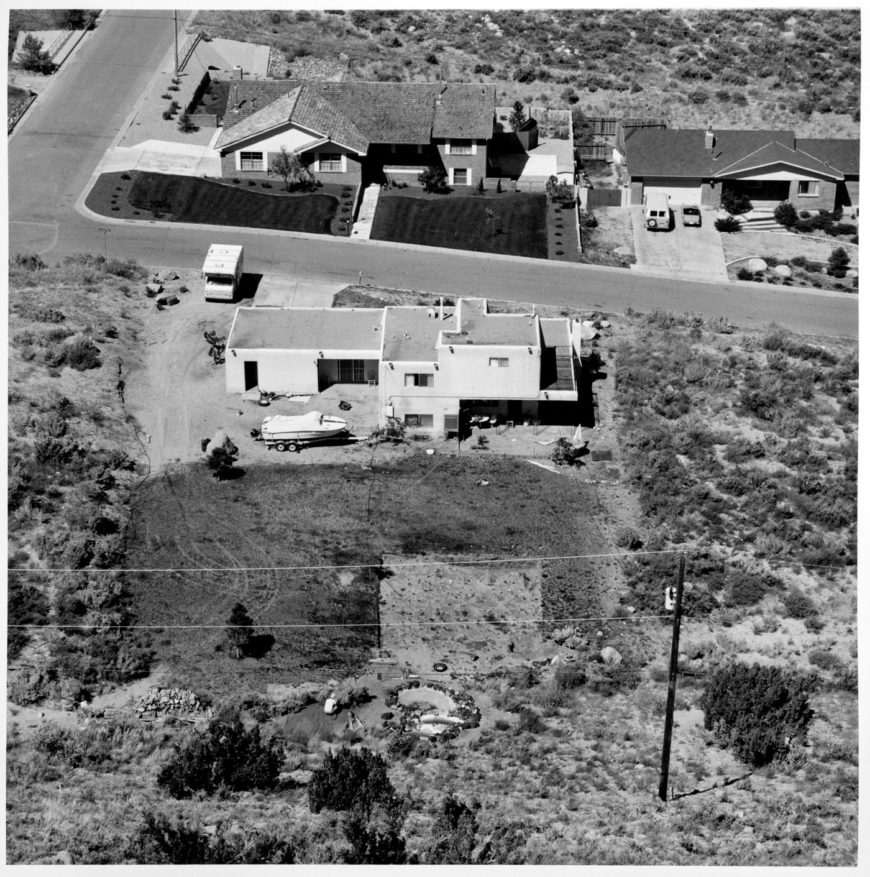

During the mid-70s, Joe Deal was chosen for an exhibition, alongside 9 other photographers, curated by William Jenkins named “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape” at the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House. This was an exhibition focusing on the effects human beings as a society have on the landscape and furthermore, the globe. Deal contributed 18 black and white photographs in a 32 cm × 32 cm format, submitting newly constructed homes against the desolate landscape of the American Southwest. These housing developments were presented at various stages of completion, using indicators of development from newly-laid roads with construction materials spread nearby, adjacent to mounds of dirt and other piles of destroyed plants.

“anthropological rather than critical, scientific rather than artistic.” – William Jenkins

Joe Deal and his colleagues rejected Romanticism from their predecessors and aimed to achieve a realistic and straightforward document of contemporary society by using emotional indifference. Through square formatting, viewers could read the landscape as if it was traces of human decision-making. The moments of too-perfect symmetry in the patterns of rocks and bushes expose the landscaping as unnatural. Joe Deal photographed suburban development in the form of construction sites which become contrasted against the large piles of refuse and empty lots regularly shown in these images that suggest the wastefulness of abandoned projects. By framing the land in this way, he created a space where his viewers must consider the cost of rapid growth in the fragile desert and how dangerously this would be impacting these natural spaces that should be protected and preserved.

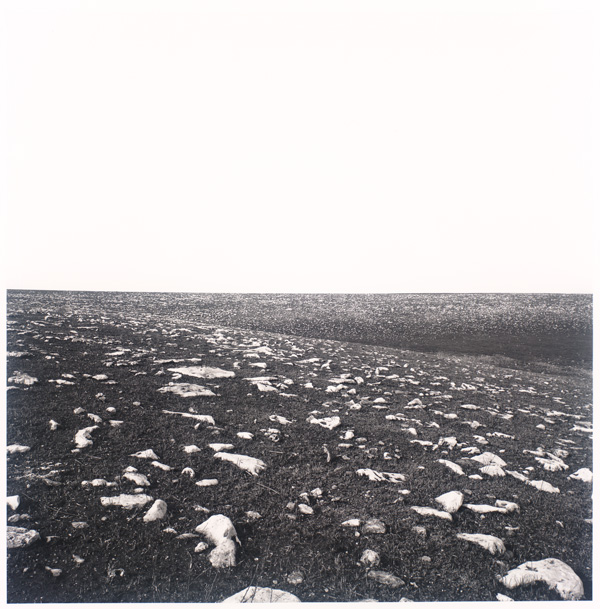

Deal trained his camera on landscapes that had been overlooked by the prominent photographers of the preceding generation, people like Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter and Minor White. Instead of majestic, snow-covered peaks or meadows dotted with wildflowers following the ideas of Romanticism and the Sublime, Deal chose to photograph places torn down and demolish irrevocably by human hands. These were landscapes most people would consider unredeemably ugly or entirely disregard without taking any notice of it, like this image of the dirt road in Wyoming. Deal wanted to blankly show the reality of the world and how the effect of humans on a non-human area will be the reason the world simply becomes no longer, without the façade of tranquillity or beauty, just the truth. Many people when first confronted with this image wouldn’t believe much about it, yet behind the image itself is a concept of urbanization.

Analysis:

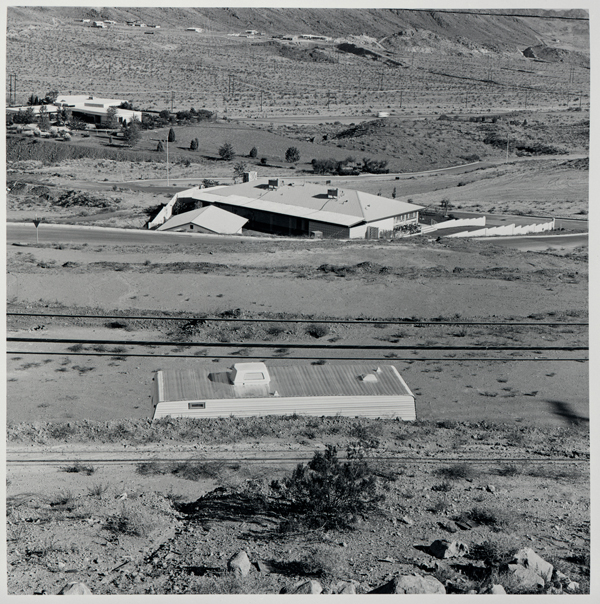

Joe Deal’s work actively focused on the destruction of these natural spaces due to the inclusion of construction sites against the decaying deserts with rubble and waste discreetly scattered around. The angle of the camera looking above and over this area whilst using a 32 cm × 32 cm format causes the viewer to face and understand the uneasy coexistence of man and nature along the San Andreas Fault in Southern California. This was a key feature continued through into his portfolio of images, “The Fault Zone,” in which he created after his huge success within the “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape” by William Jenkins. His worked acted revolutionary towards Romanticism and ideas of The Sublime in landscape photography. In a monotone way, Deal presented tract houses, industrial sites, motel, warehouses and highway projects in a deadpan and uninflected style, looking at these spaces straight on. The mundane style of this image, this desolate areas guided by three homes with a dividing road resonates with climate change and global warming as it depicts how humans are consistently “having a want for more”, urbanizing and emptying these natural spaces, blankly showing society the personal intrusion we do consciously or unconsciously. The scattered construction materials discreetly point out to the viewer, unmanipulated, alongside the tire marks swirling around on the grass, giving evidence of human interruption. The housing is shown in a more accurate 3D form through the shot being taken from a high angle, contrasting against the harsh decaying bushes surrounding, patchy and destroyed. The black and white gives a large tonal range, resembling Ansel Adams’ work, appearing perfectly exposed. The image brings a lot of sharp and fine detail taken in daylight yet even though it is quite far away, the long depth of field captures it at a wide angle. The cropped section of grass laid out purposefully at the back of the house, being the focal point, appears wilted and especially sparse being left to be destroyed by the next building development.

A few of his other exhibitions:

In these images, Deal took these images on the concept of geology and land use however are seen to be memorable from their beautiful composition and structures rather than subject matter.

In West and West: Reimagining the Great Plains, Deal used a gird format once again. In this series, Joe Deal captured much of the Midwestern United States which led to it being exhibited at University of Arizona’s Centre for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona. This series opened at Rhode Island School of Design which led to it being presented again at being presented at New York City’s Robert Mann’s Gallery. This image gives a clear notification towards the work of Roger Fenton in his series of the Valley of the Shadow of Death due to their composition. The resemblance between the two is very obvious, and has connotations towards how the landscape changes over the years.

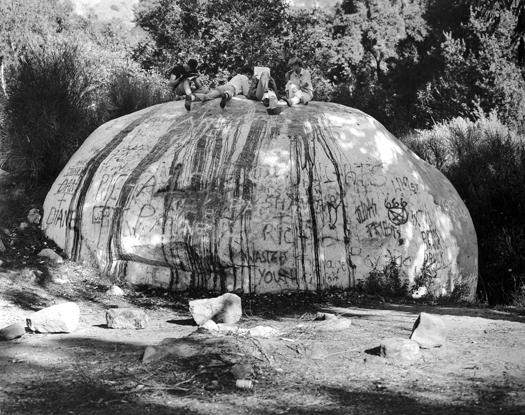

Subdividing the Inland Basin featured suburban areas east of Los Angeles, tending to include people within the landscape. This is a notification towards the way humans almost ‘conquer’ the landscape, for example in this image this is done through graffiti as if society claims these beautiful things only to destroy them in a selfish way.