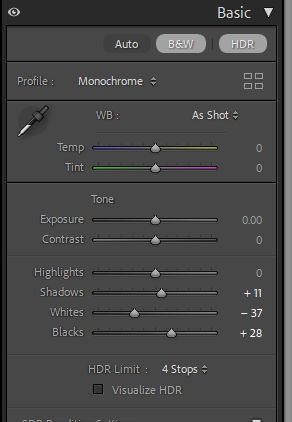

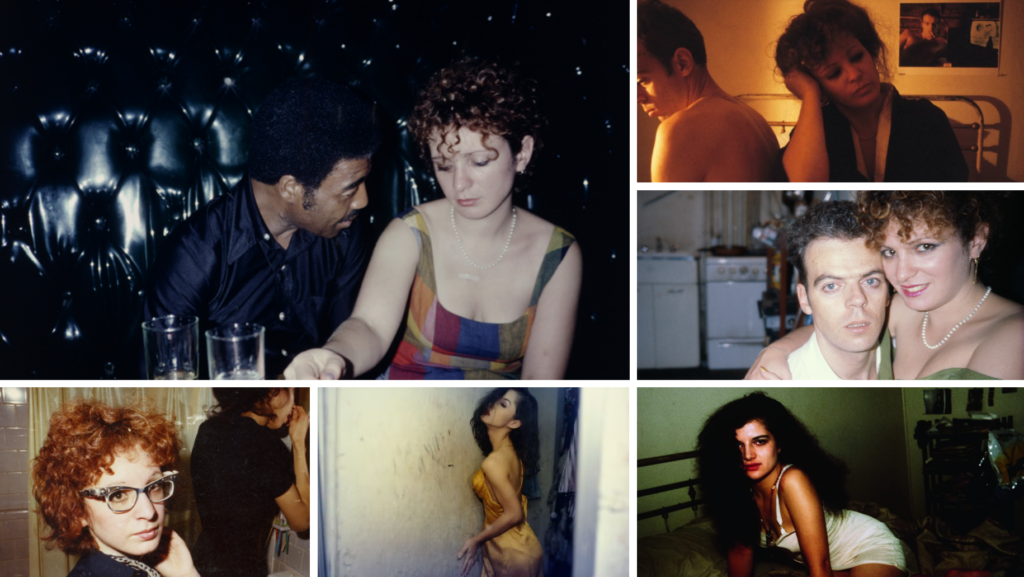

Mood board of her work

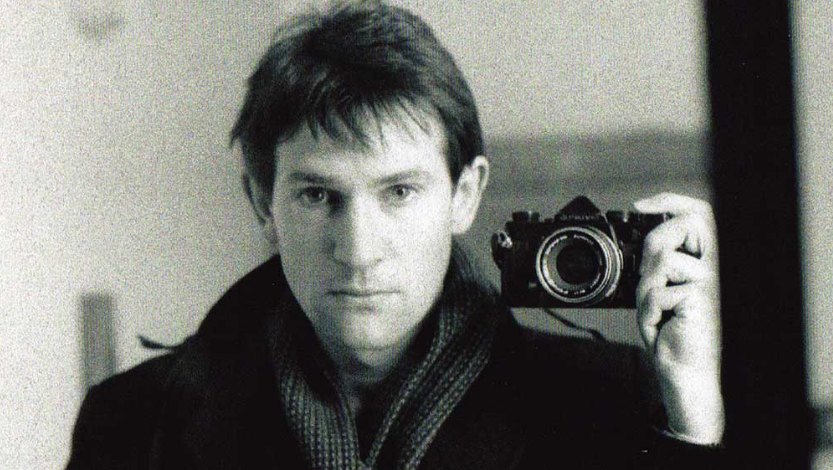

Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills comprises of over seventy black and white photographs made between 1977 and 1980. When thinking about this series, some aspects of her entire body of work immediately come to mind: disguise and theatricality, mystery and voyeurism, melancholy and vulnerability. The artist initially started these series in her apartment, using her own interior as setting for the scenes. Soon however, she moved her camera and props outside and shot in urban and rural landscapes as well, requiring a second person to assist her in taking the photograph. The artist Robert Longo, with whom she lived at that time, assisted her for a while, as well as her father, other family members, and friends.

What is Cindy Sherman’s message?

Sexual desire and domination, the fashioning of self-identity as mass deception, these are among the unsettling subjects lying behind Sherman’s extensive series of self-portraiture in various guises. Sherman’s work is central in the era of intense consumerism and image proliferation at the close of the 20th century.

Deconstructing “Woman”

Started when she was only 23, these images rely on female characters (and caricatures) such as the jaded seductress, the unhappy housewife, the jilted lover and the vulnerable naif. Sherman used cinematic conventions to structure these photographs: they recall the film stills used to promote movies, from which the series takes its title. The 70 Film Stills immediately became flashpoints for conversations about feminism, postmodernism, and representation, and they remain her best-known works.

Sherman is able to change her identity by adopting performative behaviours that have come to define femininity. Through the photographic series I have examined, Sherman’s photographs visually describe the feminist social constructionist argument that there is no natural identity behind the mask of gender. Women affirm their gender identity through performative behaviour; gender is constituted through the ongoing and repetitive assemblage of female representations depicted in culture. These behaviours position the male as a spectator, fixing his gaze on the sexualized female. Sherman’s photography is a depiction of the different ways culture defines “woman.” Her art plays on the feminist idea that gender arises exclusively within culture and deconstructs dominant gender ideologies, representing the underside of popular culture’s definition of “woman.” She exposes the arbitrariness of performativity and presents a variety of female identities that are found within popular culture, and reveals that these are nothing more than constructions. Behind each character there is no central identity. Each is a series of manipulations according to cultural conventions. There is no essential femininity; the whole self is an imaginary construct that can be changed through performativity.

The series features Sherman posing as various female stereotypes from generic black and white Hollywood B films of the 1950s. She is unrecognizable from one photo to the next, changing her appearance as she tackles the different identities, each an illustration of a cultural representation of women. Sherman plays the role of a young woman studying her own reflection. The photo visually portrays a woman assembling her identity, caught in the act of construction. It implies the lack of a fixed identity. Though Sherman is both the woman in front of the lens and behind it, she appears masked through make-up and costume, disguised to resemble familiar female stereotypes; her women are images of women, “models of femininity projected by the media to encourage imitation and identification” As in her other works, Sherman adopts the format of stereotypical female roles. However, her characters are unlike those found in magazines. “Instead these women suggest awkward adolescents or young women uncomfortable with their sexuality”. She interrogates the format and photographic genre of the centrefold and aims to destroy dominant notions of beauty and eroticism. The spread offers no context before or after the image, meaning that audiences must construct their own narrative, generally based on texts already embedded within popular culture.

She is not perpetuating the stereotypes but is assuring female audiences that there is no fixed femininity. Defending Sherman, Mulvey argues that as the gaze behind the lens, she is not perpetuating the objectification of women, but rather subverting the gaze. In each photograph, Sherman explores contemporary ideas about female identity – one being the trope of a sad female longing for a male companion. The male spectator engaged in scopophilia pleasure should feel as though he has interrupted a private movement. As the woman behind the lens, Sherman exposes the role of the male gaze in an attempt to make those who objectify the constructed woman feel like the violators they are.

“I’m disgusted with how people get themselves to look beautiful; I’m much more fascinated with the other side,” She stated in 1989

At the time, images of ailing bodies were painfully on view in the news during the AIDS crisis; these added poignancy to her investigation of the grotesque and of various types of violence that could be done to the body. In these series and throughout all of her work, Sherman subverts the visual shorthand we use to classify the world around us, drawing attention to the artificiality and ambiguity of these stereotypes and undermining their reliability for understanding a much more complicated reality.

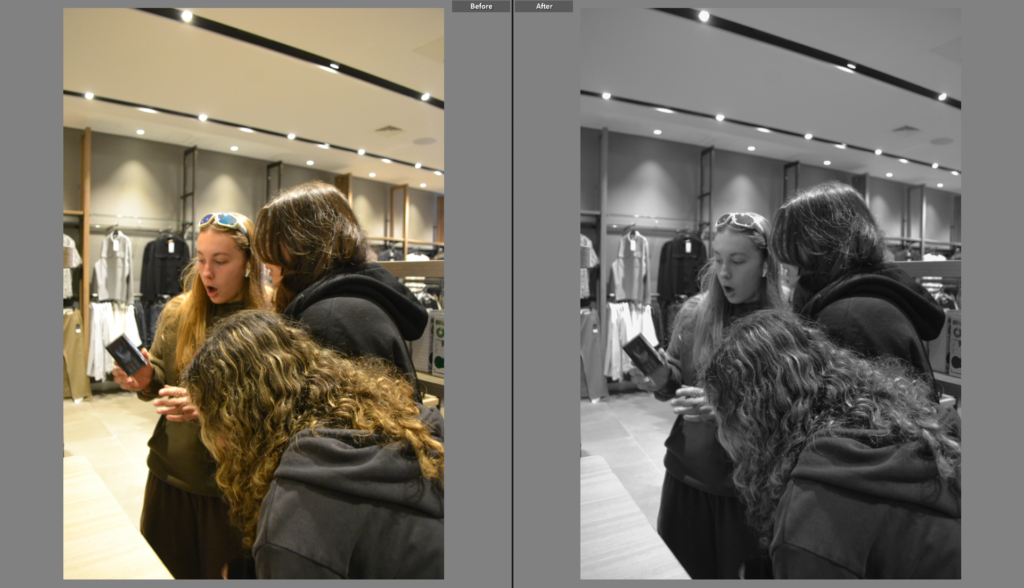

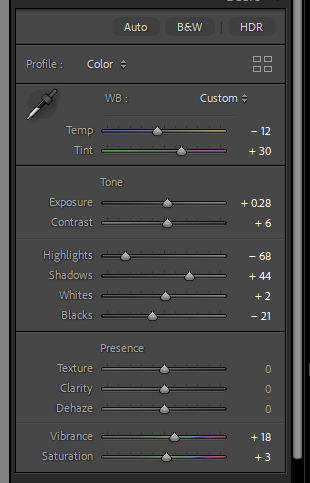

Image Analysis

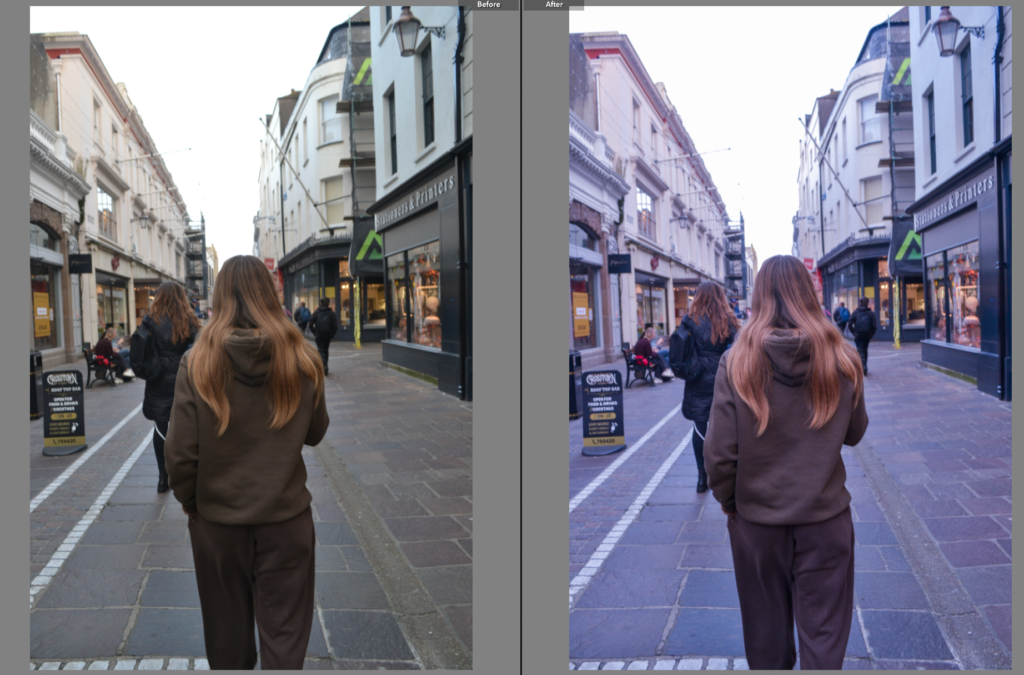

This image stood out to me the most as she is interpreting the stereotype of a woman. This could link to her message of ‘ Deconstructing a woman’, within this image there is a sense of objectification and housewife aesthetic. I state this because the image depicts a domestic scene in which the character – seemingly a housewife – stands at her kitchen sink. The construction of the picture hints at a number of possible narratives and is open to a range of analyses. Though almost cropped from the picture, the woman’s gaze – out of frame and away from the viewer, accentuated by eye makeup surely unnecessary in her own kitchen draws my attention. For me, though the image offers a portrait that I read as a stereotypical representation of a housewife from the late 1950s or early 1960s. Sherman’s gaze indicates an awareness of the world beyond the confines of the frame; the way her hand rests protectively on her stomach suggests the possibility that this is not without threat, creating a tension within the image. I think this image is a mirror due to the fact it is reflecting as of the artist herself. I also think it is a mirror as she is trying to intend an element and theme of gender roles within society during this time, but how she feels about it. She is also wearing an apron to emphasize the role she is playing. As well as this, the photo is set up to take an image of herself. It is obvious it is a staged approach due to the unfocused saucepan pointing directly at her, and the placement of the camera, clearly being on the counter to see from a lower angle. Furthermore, the gaze away from the camera also tells us it is a staged photoshoot and is not natural in any way, purely to reflect the artist. I think this image is a subjective expression, as in a way every viewer could have a different take on it. For example, as she is portraying gender roles in society in the late 1950’s she could not be intending to express herself, but how women as a whole felt during this time through a sense of reality. Therefore, she would be expressing the external world during this time. This brings to the debate is the only natural thing in this image herself? Therefore, this famous image of Cindy Sherman, reflects her as an artist, however meanwhile reflecting stereotypes of women in the 70’s. Sherman in my opinion, is sexualizing herself and playing the role of the ‘ house wife’ to execute the theme of stereotypes successfully as women in that time were seen only to make children and be there for the husband.

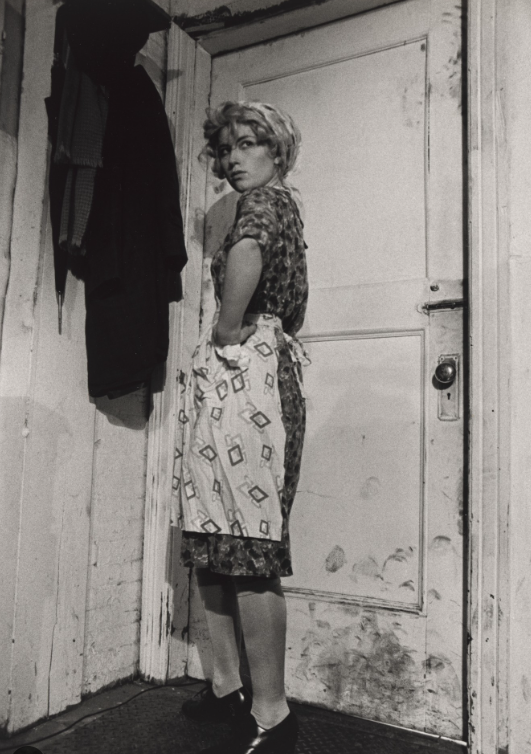

Another image analysis

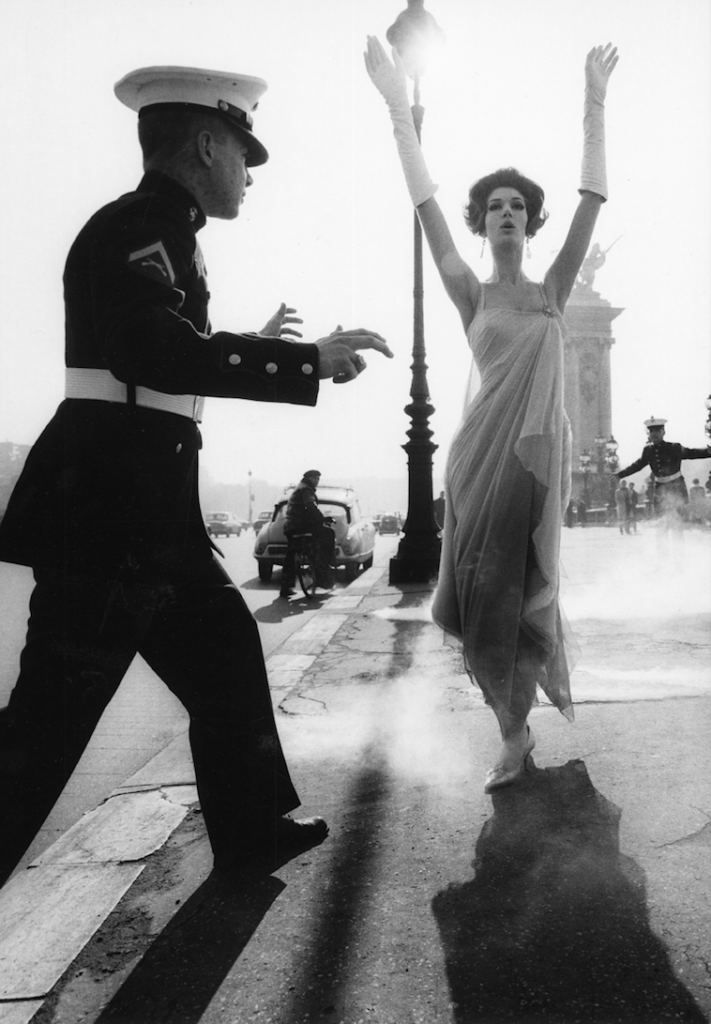

This image has slight similarities but a few differences. A main difference to me is that the previous image was of Sherman, and also taken by Sherman, or so we assume. However, this image is not Cindy Sherman and is possibly taken by Cindy Sherman. The main factor that effectively stood out to me was the apron and the gaze. This is similar to the previous image as this woman is also portraying the role of the ‘ house wife’ which is a typical stereotype of women. Although, this image has a different setting. This one does not tell much and shows a dirty door. From what I personally get from this image, could be waiting for the husband to come home or putting coats back, I assumed this through the coat pegs. This in my opinion, is ‘deconstructing women’ as a women’s role in the 1950’s was to look after their home. The image of American women in the 1950s was heavily shaped by popular culture: the ideal suburban housewife who cared for the home and children appeared frequently in women’s magazines, in the movies and on television. Another effective factor that significantly got my attention was the female gaze. The subject is looking away from the camera, possibly looking at the male in the household or to something else. Either way, this creates a sense of objectification as women were only seen to be makers of the household. The black and white is used in almost all of Sherman’s images which I like as it keeps the older aesthetic which is relevant as Sherman’s images were in the 70’s, however it also creates an element of mystery and keeps people analysing images and attempting to find a story.

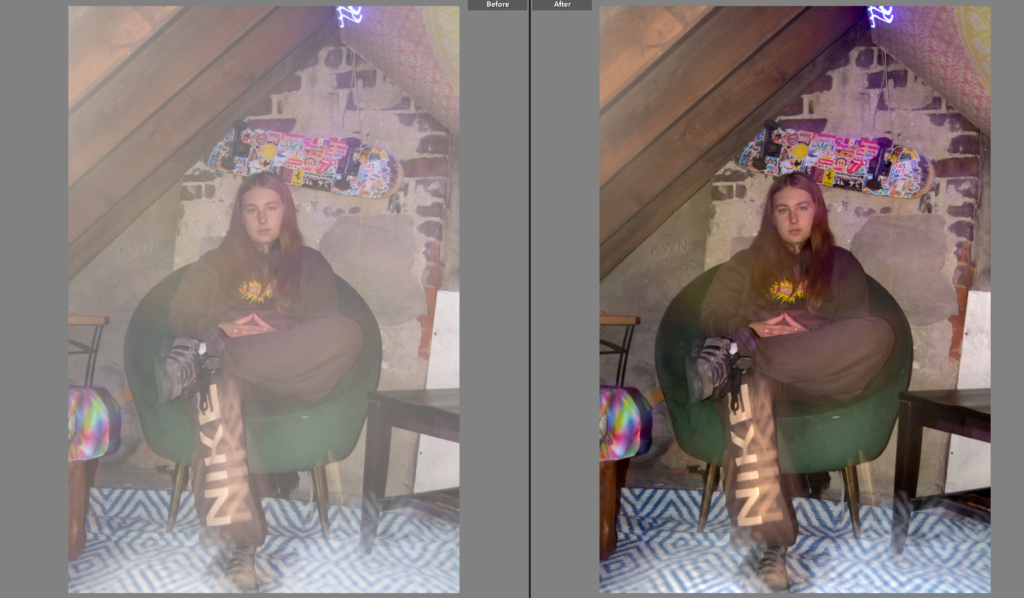

Image Analysis

This image stood out to me because of context and time lines. Cindy Sherman took her images between the 70’s and 80’s. This time line was when it was expected or stereotypical for women to be the house wife. Being the house wife normally meant for the female to be waiting at home meanwhile the husband was at work and looking after the children. Males were seen to be the educated ones and women not. This is proved through the second wave feminism movement took place in the 1960s and 1970s and focused on issues of equality and discrimination. Starting initially in the United States with American women, the feminist liberation movement soon spread to other Western countries. This allowed equal education for male and females. This image does not focus on the role of the house wife but instead of education. This significantly links to Sherman’s message of ‘ Deconstructing woman’ as Sherman has taken a self portrait of her in the library, grabbing a book. This is relevant to the timeline as this would of been a new acceptable thing for women to learn themselves equally to men. Not only this, women were seen as weak and nurturing to their children which was the only objective women were expected to do. One element that catches my eye is the female gaze, like every other one of her images. She is always looking away from the camera, potentially objectifying herself in the others, but possibly not this one. The purpose of the ‘female gaze’ becomes to connect with the female viewer via the female creator, coming together in a way that serves them, and upholding the idea that women are powerful and can control their own destiny. That is why one of the most notable differences between the male and the female gaze is intent.