Reflecting on the origin of photography, the practice of it has been evolving for many hundreds of years through the first use of the Daguerreotype in the 1840s-50s(gaining widespread popularity, particularly for portraiture), to the use of Calotypes invented in 1841.

According to John Szarkowski, photography can be viewed as either a mirror or a window. A mirror reflects reality as it is, while a window offers a view into another world or perspective. Daguerreotypes can be seen as mirrors, capturing a detailed reflection of reality, while Calotypes function more as windows, inviting viewers to explore and interpret the image beyond mere representation.

Both processes use much of the same equipment though a daguerreotype is a sharply detailed image preserved on a copper plate. In contrast, a calotype is a negative image developed on paper. Apart from that Photography has gone through many changes such as the evolution of Heliography to Daggurretypes to Calotypes to the first permanent photography being taken “View from the Window at Le Gras” to the first Kodak camera being invented in 1888.

One quote from John Szarkowski that stands out is: “It can be argued that the alternative is illusory, that ultimately all art is concerned with self-expression. If so, the illusion of this alternative is no less important, and its character

perhaps defines the difference between the romantic and the realist visions of artistic possibility. The distinction may be expressed in terms of alternative views of the artistic function of the exterior world. The romantic view is that the meanings of the world are dependent on our own understandings. The field mouse, the skylark, the sky itself, do not earn their meanings out of their own evolutionary history, but are meaningful in terms of the anthropocentric metaphors that we assign to them”.

I agree with this idea; he tells us that some art seeks to show the world as it is, while other pieces of art are reflections of what the artist feels and thinks about the world.. Through both processes, photography not only documents reality but also enhances our understanding and perception of it. Even though these perceptions can blur, the opposition between seeing the world and seeing it how we interpret it gives us distinct artistic experiences.

Photography can serve as a means for reflection and self-expression. The mirror metaphor emphasizes the “subjective nature” of photography, where the image becomes a reflection of the photographer’s emotions, beliefs, and worldview. Photographs taken in this mode often reveal more about the individual behind the camera than the subject in front of it. This is particularly relevant in portraiture or self-portraiture, where the photographer uses the medium to explore identity, memory, and personal history.

The act of photographing can be deeply personal, allowing the photographer to project their inner thoughts or emotions onto the image. This idea is supported by theorists such as Roland Barthes, who, in Camera Lucida, writes about the notion of the “punctum”(a detail in a photograph that speaks directly to the viewer’s personal experience, triggering emotion or memory). For him, a photograph can reflect an individual’s subjective reality, a private connection that mirrors their world.

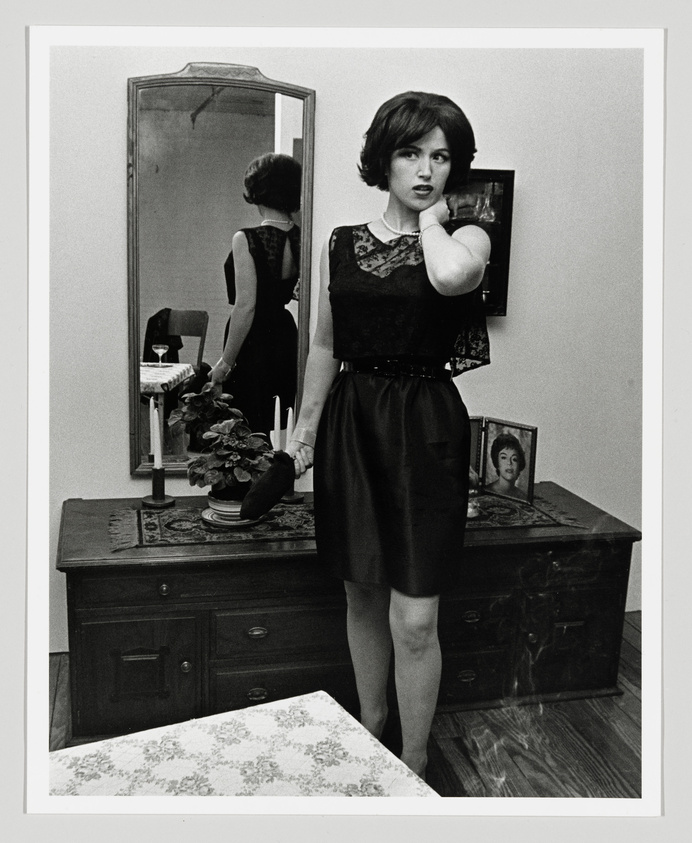

Moreover, photographers such as Cindy Sherman have used the camera as a tool to explore identity by creating highly stylized self-portraits that challenge societal norms and question the nature of identity itself. Her work in her Untitled Film Stills series reflects how photography can mirror societal expectations while simultaneously critiquing them. In this sense, photography as a mirror offers a way to interrogate identity, revealing as much about the photographer’s internal world as the subject being captured.

The image presents a subjective and staged approach to image-making, embodying what John describes as the mirror in photography rather than depicting reality. In the image itself, Cindy presents a female character that seems to be drawn from a 1950s dark film, placing herself within a carefully composed scene that hints at a bigger story behind it. The vagueness in the image is a critical aspect of Sherman’s work which often relies on staged elements to explore themes such as identity, gender, and media stereotypes. The photo is less about the subject e.g. the woman in the scene but more about Cindy Sherman’s exploration of how identity can be both constructed and deconstructed through visual symbols.

Szarkowski’s Mirrors and Windows supports this interpretation, as he says, “The romantic view is that the meanings of the world are dependent on our understandings.” This quote aligns with Cindy’s work as her images are constructed with her subjective vision which is shaped by the cultural/ societal expectations she explores. Her work invites viewers to consider how these “meanings” are imposed upon the image through a culturally constructed lens which can embody John’s concept of the mirror by reflecting society’s inner psychological landscape rather than an “objective” truth about the character she portrays.

Jed Perl argues that while Sherman’s images are captivating they also risk becoming “staged impersonations” that sometimes can lack the depth of genuine self-reflection. He suggests that such work can sometimes feel like performative constructions rather than genuine mirrors of the artist’s psyche. This critique introduces a layer of tension within Cindy Sherman’s approach that questions whether her work captures self-expression or simply recreates surface-level models

Overall, the image illustrates Szarkowski’s notion of the mirror. Yet as Perl’s critique suggests Sherman’s staged approach raises questions about authenticity and whether her images fully achieve the “self-expression” John envisions. This debate enriches the interpretation of Sherman’s work which emphasizes the complexities within staged photography as both personal expression and social commentary.

On the other hand, photography can act as a window into the world, by providing an objective or semi-objective view of the external reality. In this example, photography is seen as a tool for documentation and observation, allowing viewers to witness events, places, or moments they might never personally experience. The window metaphor can highlight the transparent nature of photography where the camera becomes a medium through which the viewer can access the world beyond their immediate surroundings.

The origins of photography are deeply tied to its use as a window. Early photographers like Mathew Brady, who documented the American Civil War used the medium to capture historical moments with an eye toward objectivity. These photos served as windows into the reality of war, which offered viewers a direct glimpse into a brutal and chaotic world. This function of photography as a window persists in photojournalism/ documentary photography where the aim is to capture reality as truthfully and as authentic as possible.

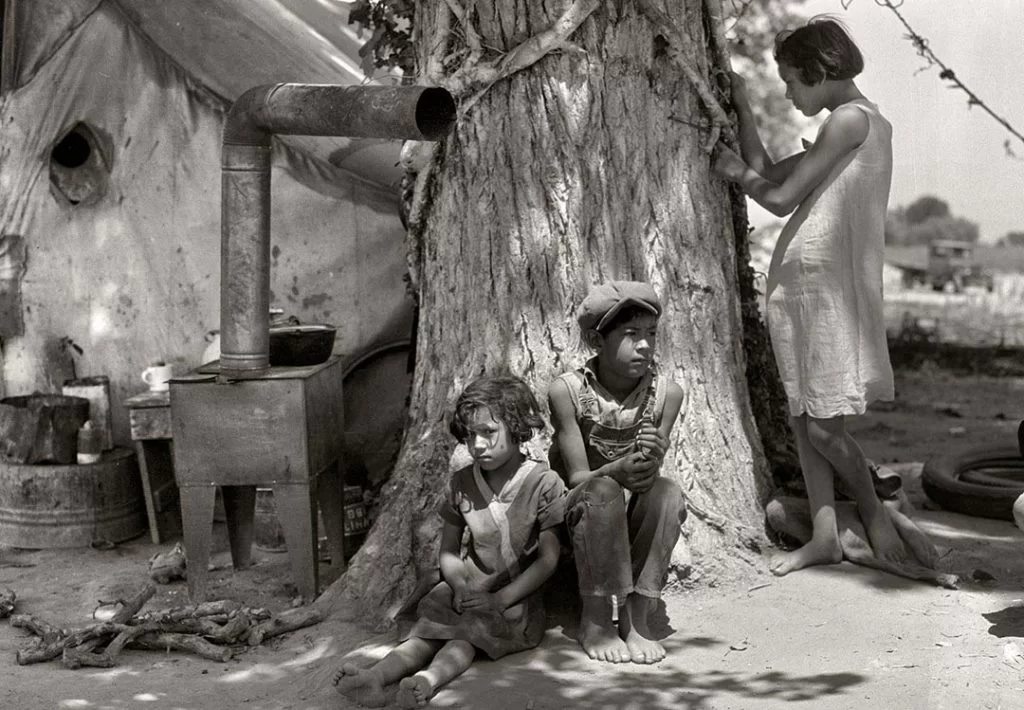

According to John photographs that function as windows allow viewers to look beyond their personal experience and into the lives of others, which fosters a sense of empathy and understanding. Documentary photographers like Dorothea Lange, who captured the struggle of migrant workers during the Great Depression, used their cameras as windows to reveal societal issues and human suffering, hoping to inspire social change through the power of visual storytelling.

Additionally, photography as a window extends to the exploration of the natural world and landscapes. The works of photographers like Ansel Adams depict vast, majestic scenes of nature that offer a window into the sublime beauty of the world. These images provide viewers with access to places they may never visit, acting as visual windows that transport them to new environments and experiences.

While photography can function as either a mirror or a window, many images blur the line between the two, serving as both a reflection of the photographer’s perspective and a view of the external world. The very act of taking a photograph involves a blend of subjectivity and objectivity. Even in documentary or journalistic photography, where the aim is to capture an objective reality, the photographer’s choices—what to include in the frame, when to take the shot, and how to present the image—introduce a level of personal interpretation.

Street photography, for example, often embodies this tension between mirror and window. The photographer captures candid moments in public spaces, offering a window into everyday life. Yet, at the same time, the choice of subject, angle, and framing reflects the photographer’s unique vision and interpretation of the scene, turning the photograph into a mirror of their worldview. The work of photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson demonstrates this balance, where the “decisive moment” captures reality while also conveying the photographer’s sense of timing, composition, and emotion.

Furthermore, in contemporary art photography, many images intentionally play with the concepts of mirrors and windows, inviting viewers to question the boundaries between reality and representation. Andreas Gursky’s large-scale photographs, for instance, offer expansive views of urban and industrial landscapes, functioning as windows into the complexity of modern life. However, his manipulation of the images—through digital editing—challenges the idea of photography as a transparent window, instead turning the image into a reflection of how we perceive and construct reality in the digital age.

In conclusion, photography can be understood as both a mirror and a window, offering reflections of the photographer’s subjective reality while simultaneously providing views into the external world. The distinction between these two roles is not always clear-cut, and many photographs function as both—revealing personal perspectives while documenting the world in a way that invites interpretation and engagement. Theoretical approaches by figures such as Barthes, Szarkowski, and others highlight the complexity of photography’s relationship to truth, identity, and representation. As both a mirror and a window, photography remains a powerful medium for exploring the self and the world, constantly negotiating the boundaries between reality and perception.