Photography originated back in 1822 as an instantaneous form of revealing secrets beyond the world in a nonchalant form, giving nothing away at the same time. Due to the etymology of photography being ‘drawing with light’ this art form if to turn the ordinary into the extraordinary, evoking a variety of emotions and thoughts, creating wonder about what lies beyond the frame of the image.

THE CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY:

Camera Obscuras and Pinhole photography:

In his Book of Optics written in Cairo between 1012 and 1021, Alhazen (or Ibn al-Haytham), is said to have created the camera obscura alongside the pinhole camera in order to ‘fix the shadows’. However, it is said that a camera obscura was a tool used since 400BC. A camera obscura consisted of a large box with a hole in it which projected an image of its surroundings onto the wall inside. This allowed the outside world to pour in and act as an optical phenomenon, with the time taken for this alternating from several minutes to several hours depending on the desired image that was being projected. The environment projected would be presented upside-down and ‘twice as natural’, used for artists to sit inside the box and create paintings or drawings of this area, using darkness to see light. This was called pinhole photography.

Now, in more modern times, the camera obscura has been made into an electronic chip.

Below is an example of the camera obscura in use more recently. This was done by Abelado Morell of the Santa Maria Della sauté in Venice:

Joseph Nicephore Niepce and Heliography:

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, was a French inventor who is recognised widely as one of the earliest pioneers of photography through his development of heliography, creating arguably the oldest surviving image made with a camera:

Heliography is a process where Bitumen of Judea (a natural tar from ancient times acting as a light-sensitive material) was coated in a thin layer on a pewter plate and was exposed to areas surrounding his estate such as buildings or the countryside. He experimented with this using zinc, glass, copper and limestone (lithography) too, creating different etches using acid. This image was exposed for 8 hours and it provides no information of the weather, time or season.

Louis Daguerre and Daguerreotypes:

In 1824, Louis Daguerre created the visual experience known as a Daguerreotype, described as ‘a mirror with a memory’ and created ‘people on the edge of being present’. This would be done initially by polishing a metal plate and laying silver grains upon the surface of it due to them being light-sensitive. Then, this would be placed inside a large format camera and exposed to light from hours to days in order for the light to be reflected back through. After this, the plate would be heated, then cooled with water with extreme caution. This was because if the daguerreotype was touched in the slightest, the image would melt away and be destroyed, wasting the many tools that had to be used. These had high monetary value too, meaning that if the Daguerreotype had been melted away, the artist would have missed out greatly.

As the daguerreotypes were so fragile, they would be specifically placed into different kinds of housing such as an open model, a folding case or in jewellery boxes: wooden ornate boxes dressed in red velvet.

Henry Fox Talbot and Calotypes:

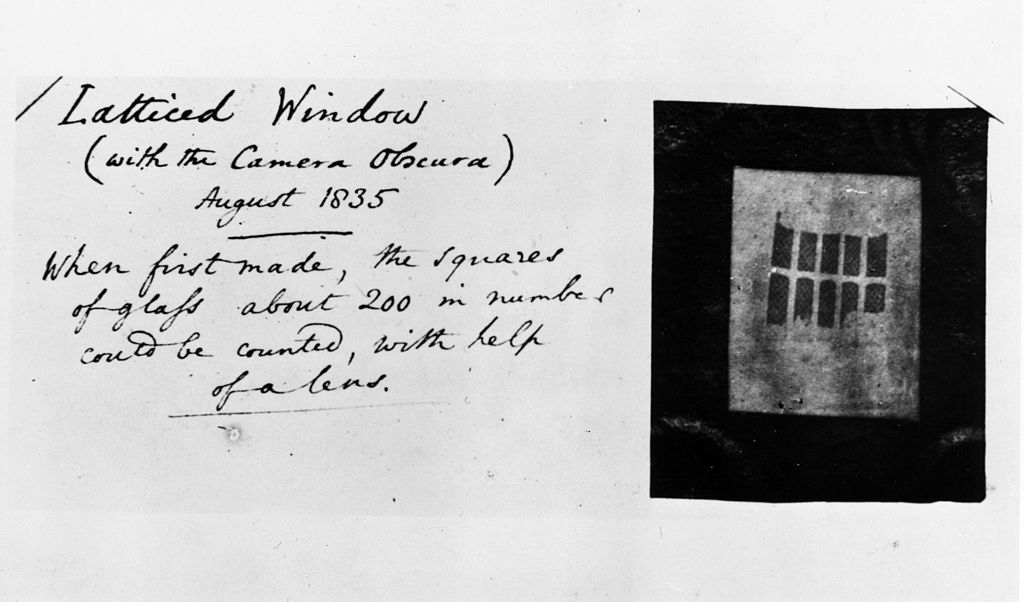

Henry William Fox-Talbot was an English member of parliament, scientist, inventor and a pioneer of photography for his salted paper and calotype processes. Talbot first began by applying “silver salts” onto salted paper, creating silver nitrate reactions from the light-sensitivity. This was then exposed to light for many days and then darkened producing negative images. These appeared like shoebox sized cameras and were named mousetraps and were very difficult to use because if it was disturbed it may just get darker and darker so that its only experienced momentarily.

Overall, calotypes were extremely better than Daguerreotypes due to it being easily distributed, reproduced and were much cheaper. Whilst they both used light sensitive silver salts, the Daguerreotypes required a lot more tools and metal plates which had high monetary value.

Robert Cornelius and self-portraiture:

Robert Cornelius became a pioneer in photography through his daguerreotype self-portrait in 1839:

The back of the image read ‘The first light picture ever taken’, becoming the first known photographic portrait in America.

Julia Margaret Cameron and Pictorialism:

Julia Margaret Cameron was an English photographer considered to be one of the best portraitists in the 19th century. She is not only known for her soft-focus close-ups of famous Victorians but also her illustrative images which depicted characters of Christianity, mythology and literature.

However, she was often criticised by the photographic establishment for her poor technique – some images are out of focus, her plates are sometimes cracked and her fingerprints are often visible.

A stapling example is a photograph taken 1867 of Sir John F. W. Herschel; a scientist, mathematician and photographic experimenter. Emerging from the shadows with tousled hair and deep facial lines, it tells a story of a man devoted to the intellectual life.

Around 1863, Cameron received a sliding-box camera for Christmas from her son-in-law and daughter, sparking her immense interest in photography. This led her to turn her coal-house into a dark room, converting the chicken coop into a studio to work in.

“I began with no knowledge of the art… I did not know where to place my dark box, how to focus my sitter, and my first picture I effaced to my consternation by rubbing my hand over the filmy side of the glass“

Whilst Cameron took up photography as an amateur, she considered herself to be an artist and took the matter very professionally, copyrighting and publishing her work. In 1865, she became a member of the Photographic Society of Scotland and arranged to have her prints sold through the London dealers P. & D. Colnaghi, with her series of prints named Fruits of the Spirits being exhibited solo at the British Museum in November 1865. Overall in her 12 year career, she produced over 900 photographs.

PICTORIALISM: ‘an approach to photography that emphasizes beauty of subject matter, tonality, and composition rather than the documentation of reality‘

This was a movement which dominated photography during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This depicted common and regular images in a more psychological and spiritual way, focusing on the compression of space and blurring detail, as well as patterning light across the image. Pictorialists also involved soft focus and the use of additions of the lens or filters in the dark room. This reinforced the idea of photography being an art alongside painting and drawing. To create this dreamy visual effect, a chiaroscuro technique was often implemented to reveal these ideals of beauty, truth and the picturesque. However, pictorialism was often criticized for being too emotionally shallow because the main point behind these images was the focus on formal qualities such as the texture, tone and composition, disregarding the content or meaning behind the actual image.

Henry Mullins and Carte-de-Visit:

Henry Mullins is one of the most prolific photographers represented in the Societe Jersiase Photo-Archive, producing in the 19th century. He captured 9,000 portraits of islanders within Jersey from 1852 to 1873 at a time when the population was around 55,000, proceeding to place them in an order of levels of social class in albums. He began his career by working at 230 Regent Street in London in the 1840s, then moving to Jersey in July 1848, setting up a studio known as the Royal Saloon, at 7 Royal Square. Initially he engaged in a partnership with someone named Mr Millward, yet very little is known about him. By the following year he was working alone and he continued to work out of the same studio for another 26 years.

Henry Mullins’ work of 19th century Jersey is highly politicised, taking images of Jersey political elite (E.g. The Bailiff, Lt Governor, Jurats, Deputies etc), mercantile families- involved in trade (Robin, Janvrin, Hemery, Nicolle etc.), military officers and professional classes such as doctors, bankers and advocates. He organised these images from the most powerful roles, to the lesser powerful.

CARTES DE VISITE: ‘visiting card’ or a close-trimmed portrait photograph approximately 2¹/₄×3³/₄ in. intended as a substitute for a visiting card.

Mullins specialised in Cartes de visite, in which the photographic archive of La Société contains a large amount of these (online archive being 9600 images). The Cartes de visite small albumen print. This is described as the first commercial photographic print produced using egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper which is quite interesting as this is would be very rare to see now. Because the image emerges as a direct result of exposure to light, without the aid of a developing solution, an albumen print may be said to be a printed rather than a developed photograph. Usually, this consisted of a small thin photograph mounted onto a thicker piece of card, however Mullins placed his work into an album.

Many of these images contained the island’s most affluent and influential people, alongside officers of the Royal Militia Island of Jersey, for whom it was very popular to have portraits taken, as well as of their wives and children. The images of the officers document the change in generations as they do not look like the general person today, showing the fashion for long hair, whiskers and beards in the mid-1800s. Their appearance makes it difficult for the viewer to differentiate who is who as they were styled almost identically during this time.

He then arranged this compilation of images into a diamond cameo:

Its name is derived from the diamond-like shape that the images are laid out into. These diamond cameos consisted of 4 images of the same person looking in different directions and at different angles. This is a really effective way to produce a final set of images as they are consistent and act in a poised manner of taking headshots. Also, it centers around the person and makes the image become a question of who the person is and why they have been presented at this status, depending on the kind of clothes and hairstyles they presented.

WHO IS FRANCIS FOOT?

Francis Foot was born in Jersey in 1885 to mother and father, Louisa Hunt and Francois Foot. His father was a china and glass dealer along Dumaresq Street which was one of the most affluent areas in St Helier at the time. Francis Foot began his working life as a gas fitter, however shortly after this began he started to become fascinated by photography, the early phonographs and gramophone records. Through this, he realised that he could earn a living using this. Taking on a second shop on Pitt Street, Francis worked as a photographer however remaining on Dumaresq Street, his mother and father sold records, gramophones and other wares until his father passed away. After this, Francis remained working in Pitt Street.

Some of Foots images were published as postcards even though many of his images featured portraits of his family. Alongside this, he also took 16mm black and white cine films regarding many different types of events such as:

- Aircraft landing on the beach at West Park,

- A visit by HMS Sheffield,

- Cattle shows,

- The Battle of Flowers at Springfield,

- The Liberation,

- The visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth,

Eventually the gramophone and record department of his work became increasingly more important and had to take over the larger shop on Pitt Street in which Francis sold vinyl records during the 1950s and 60s.

In 1996, La Société Jersiaise received a collection of glass plates and other photographic material, leading them to now behold 322 images of a diverse array of Jersey such as:

- The Battle of Flowers,

- St Helier Harbour,

- Shipwrecks,

- Fetes,

- Coastal and country views,