‘buildings where anonymity is accepted to be the style’.

Bernhard “Bernd” Becher and Hilla Becher, née Wobeser (1931–2007; 1934–2015) were a married collaborative duo of German conceptual artists and photographers. In the forty years in which they worked together, they are best known for their extensive focuses on the disappearing industrial structures and buildings, often arranging them into grid formats. They are said to have changed the course of late twentieth- century photography and pioneering the thought behind these industrial spaces being something made, artifacts frozen in time to tell a story of history.

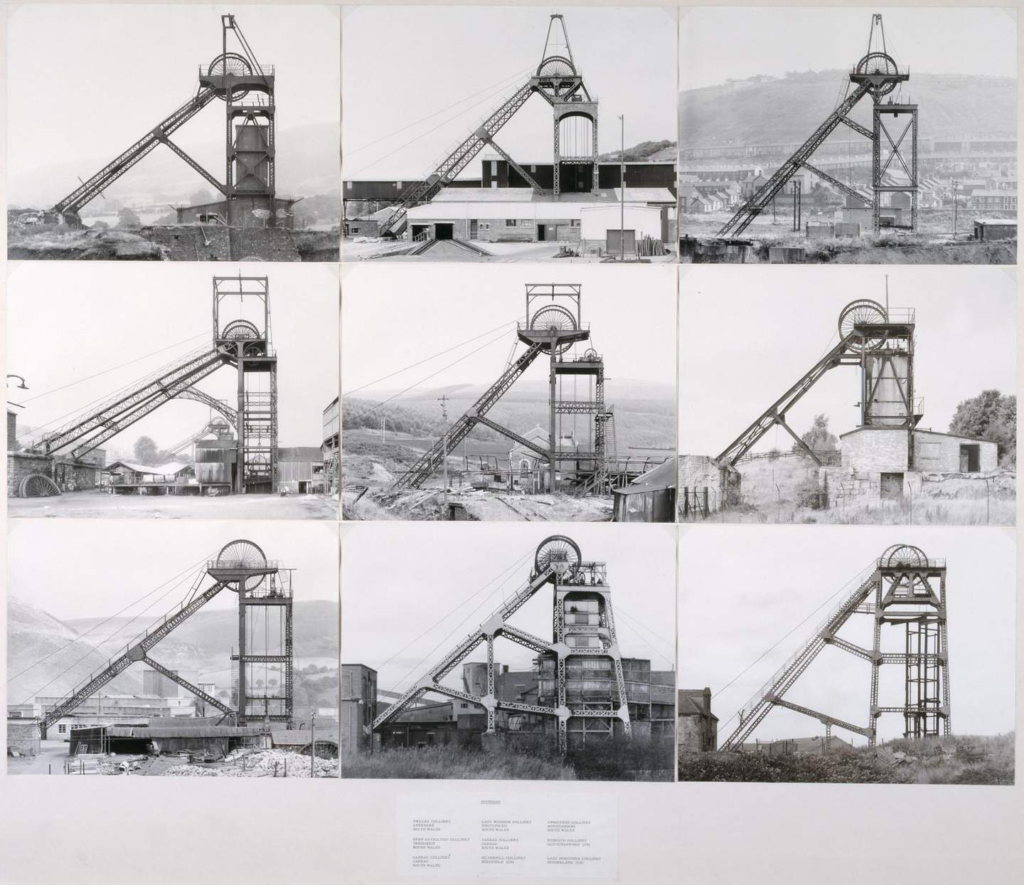

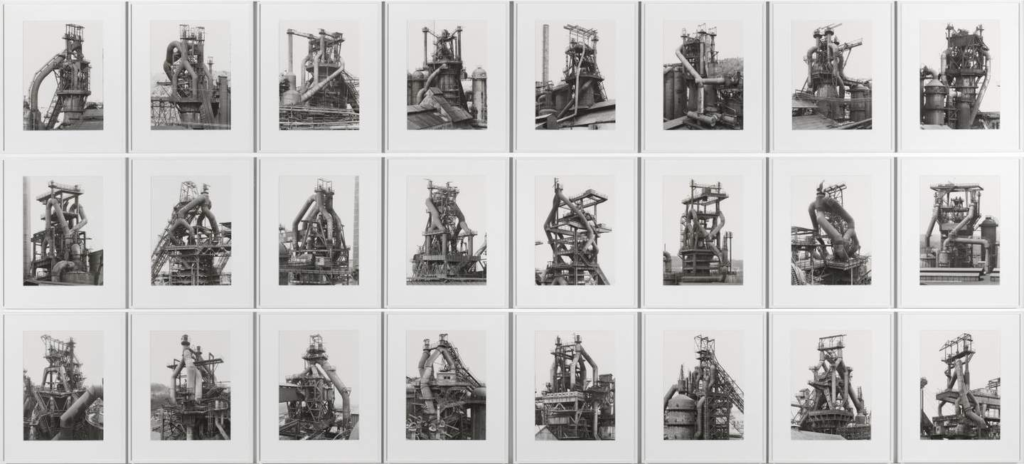

They originally began working together in 1959 after meeting each other at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1957. Bernd began as a painter whilst Hilla was a trained commercial photographer, marrying after two years. The documentary style of their images were of water towers, coal bunkers, gas tanks and factories just to name a few, presented in black and whit in the form of typologies. These images never including people and just focused on the industrial structure. These images focused on Western Europe and North America where the modern era was fuelled. The Becher’s tended to call the subjects of their work ‘anonymous sculptures’, leading to this referral, and produced a very successful photobook of these images in 1970. This meant that in 1990, they received an award at the Venice Biennale for sculpture due to the powerful ability they had to illustrate the sculptural properties of architecture in such an aesthetic way. The themes represented in their work was commonly about overlooked beauty and compiling an in-depth study of the intricate relationship between form and function. This addressed the effect of industry on the economy and environment.

Each 40 x 30 cm

Typologies:

a set of images made with a common subject or idea in mind, repeated through out the set.

One of the first photographic typological studies was by the German photographer August Sander, whose epic project ‘People of the 20th Century’. He produced a large volume of portraits entitled ‘The Face of Our Time’ in 1929. Sander categorised his portraits according to their profession and social class. This methodical and disciplined approach later influenced many other photographers at an enormous scale, notably Bernd and Hilla Becher. Each image is replicated in a consistent style, shooting from the exact same angle and distance from the same building, documenting how the building would change over time going unnoticed. This not only makes the viewer become more considerate of their surroundings, but question the subject’s reasoning/place in the world. It also invokes questioning revolving around the rate at which we develop as a society – for example these industrial structures are being taken down for developments to move towards urbanization and modernization. Bernd and Hilla Becher also used this technique to group images together of structures that had similar styles, just with size differentiations, yet still keeping that structure consistent throughout the grid. Each subject has a relationship with the other.

They used a large-format camera and carefully positioned it under overcast skies. This was necessary to record shadowless front and side elevation views of their subjects in a deadpan way.

Their key pieces of work began with their first photobook in 1970 named ‘Anonymous Sculptures’, being their most well-known piece. The title was chosen through not only the referral of their images as ‘sculptures’ but due to Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades:

This noted that the Bechers acted as if these industrial pieces of history were like found objects. This photobook acted like an encyclopaedic inventory, documenting kilns, blast furnaces and gas-holders, categorising them into their related sections.

Bernd and Hilla’s work left a legacy that led to influence minimalist and conceptual artists such as:

- Ed Ruscha

- Carl Andre

- Douglas Huebler

Alongside being photographers themselves, they were also professors at The Dusseldorf School of Photography, continuing to influence their German students such as Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth. Bernd died on June 22, 2007 in Rostock, Germany, while Hilla died on October 15, 2015 in Düsseldorf, Germany. Today, their works are included in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Tate Gallery in London.