What is the new topographics?

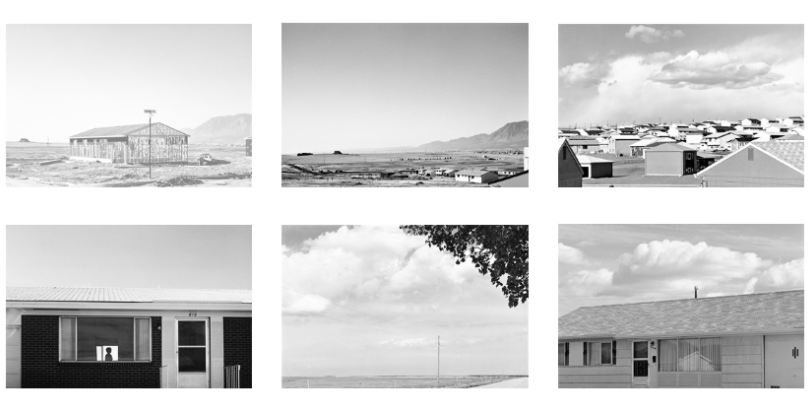

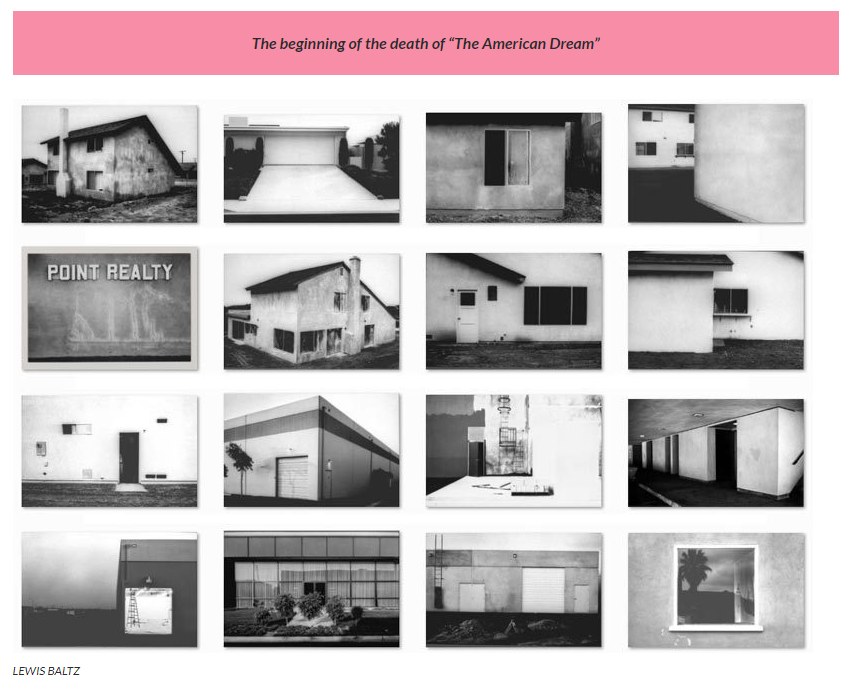

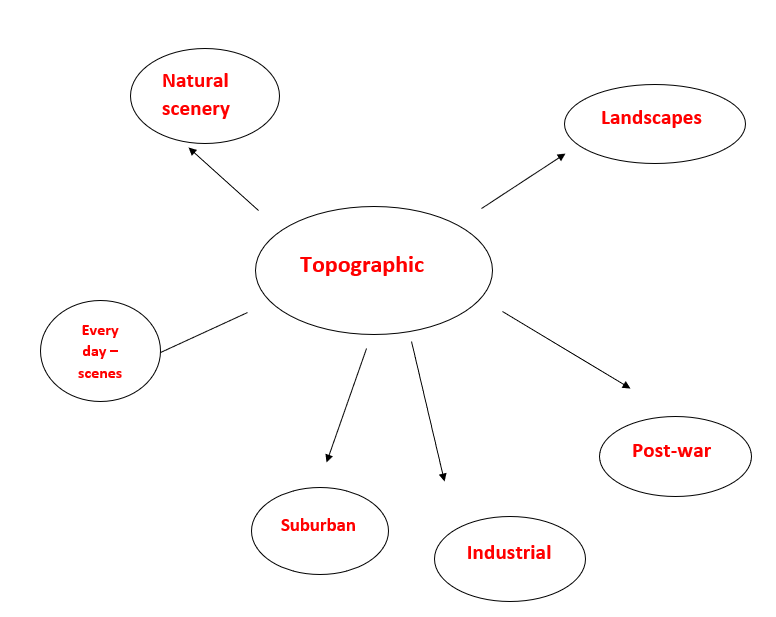

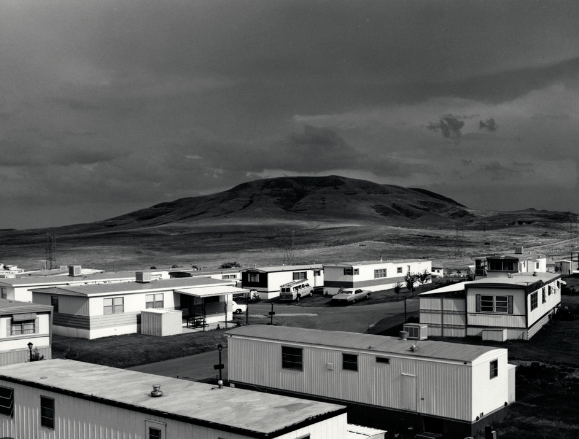

New topographics was a term coined by William Jenkins in 1975 to describe a group of American photographers (such as Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz) whose pictures had a similar banal aesthetic, in that they were formal, mostly black and white prints of the urban landscape.

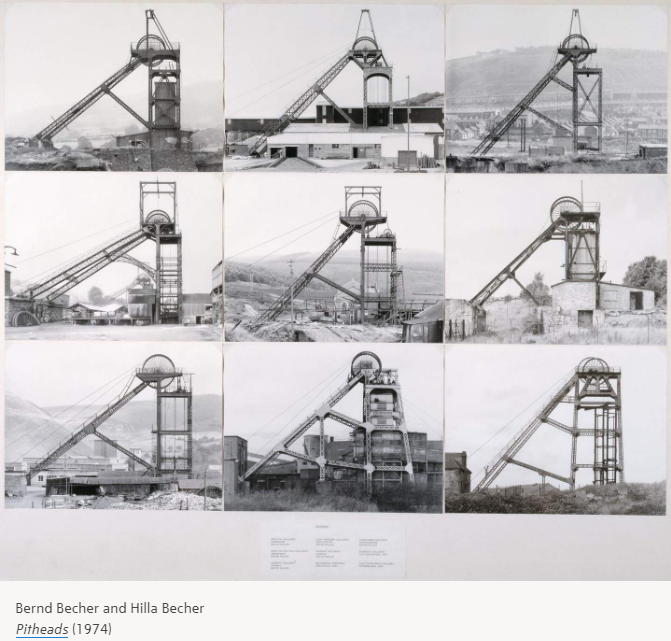

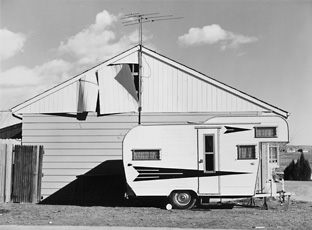

The New Topographics documented built and natural landscapes in America, often capturing the tension between natural scenery and the mundane structures of post-war America: parking lots, suburban homes, crumbling coal mines. The photographs, stark and documentary, are often devoid of human presence.

Jenkins described the images as “neutral” in style, “reduced to an essentially topographic state, conveying substantial amounts of visual information but eschewing entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion, and opinion”.

Topographics in general is a technique in which a scene, usually a landscape, is photographed as if it were being surveyed from afar.

On the one hand, New Topographics represented a radical shift by redefining the subject of landscape photography as the built environment. To comprehend the significance of this, it helps to consider the type of imagery that previously dominated the genre in the United States.

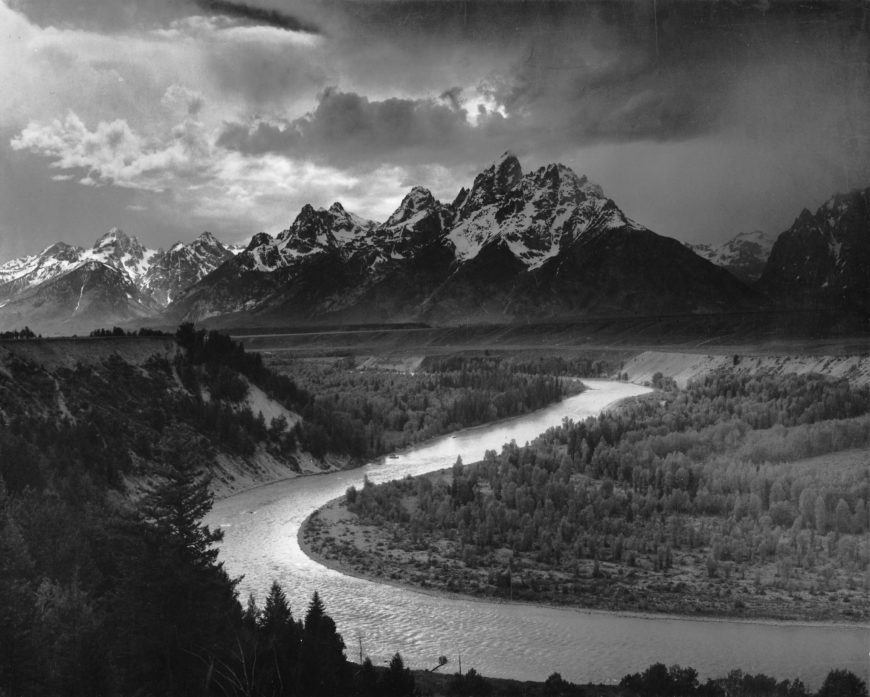

Beginning in the 1920s, Ansel Adams cultivated an approach to landscape photography that posited nature as separate from human presence. Consistent with earlier American landscape painting, Adams photographed scenery in a manner intended to provoke feelings of awe and pleasure in the viewer. He used vantage points that emphasized the towering scale of mountain peaks, and embraced a wide tonal range from black to white to record texture and dramatic effects of light and weather.

Ansel Adams, “The Tetons—Snake River,” Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, 1942

Adams wanted his pictures’ viewers to feel as uplifted as he had when looking at the scenery in person. His heroic, timeless photographs contributed to the cause of conservationism – the environmental approach that seeks to preserve exceptional landscapes and protect them from human intervention.

Despite The New Topographics being an interesting new genre for many photographers to experiment with, it was actually a controversial technique in which many photographers do not like the look of it. This may be because the photos include more of the man-made world rather than the natural world, which many can argue is more “boring”.

“I don’t like them—they’re dull and flat. There’s no people, no involvement, nothing.”

However, many photographers do enjoy photographing the man-made world as it is an opportunity for the audiences to realize how much humans rely on it. The world we live in today would not be remotely similar if we did not have all of the up-to-date buildings and technology, which is useful to everyone, every day.

“At first it’s stark nothing, but then you look at it, and it’s just about the way things are.”

“I don’t like to think there are ugly streets in America, but when it’s shown to you—without beautification—maybe it tells you how much more we need here.”

The stark, beautifully printed images of the mundane but oddly fascinating topography was both a reflection of the increasingly suburbanised world around them, and a reaction to the tyranny of idealised landscape photography that elevated the natural and the elemental.

Post-war America struggled with:

- Inflation and labour unrest. The country’s main economic concern in the immediate post-war years was inflation.

- The baby boom and suburbia. Making up for lost time, millions of returning veterans soon married and started families.

- Isolation and splitting of the family unit, pharmaceuticals and mental health problems.

- Vast distances, road networks and mobility.

Robert Adams, The New West

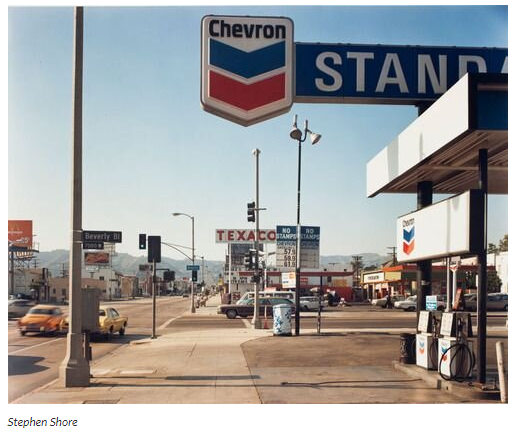

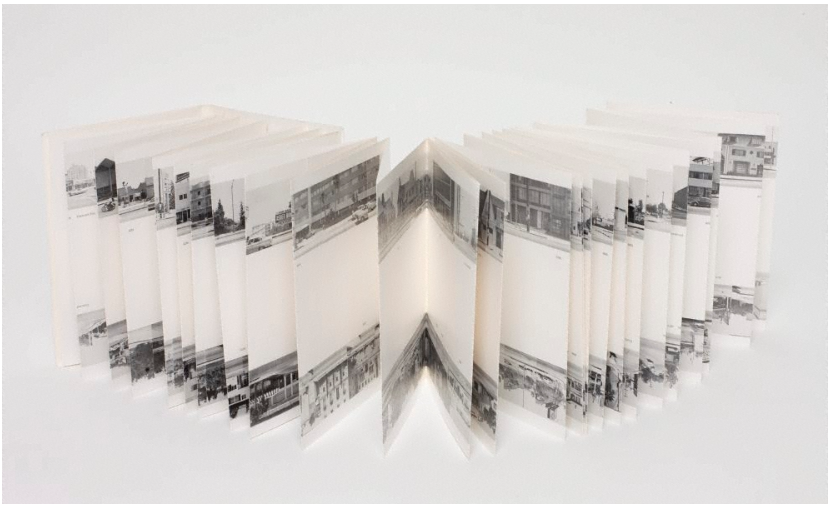

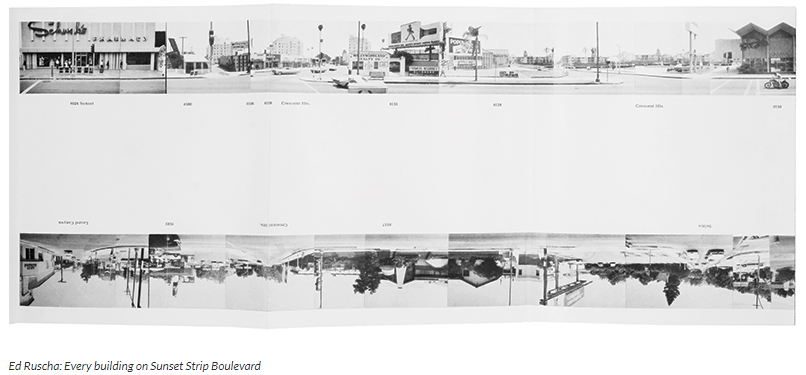

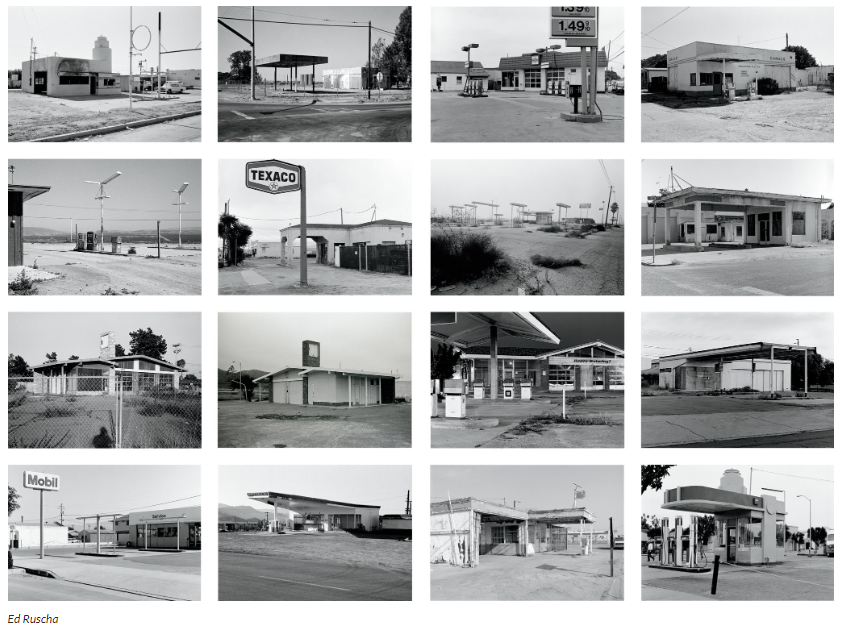

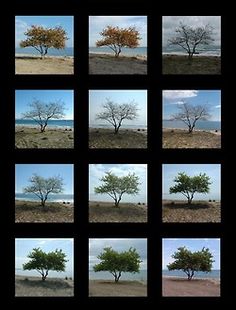

The artist Ed Ruscha is famous for his paintings and prints but is also known for his series of photographic books based on typologies, among them every building on the Sunset Strip, 26 gasoline stations, some Los Angeles apartments, and 34 parking lots. Ruscha employs the deadpan style found in many photographic topologies.

Parking lots, suburban housing and warehouses were all depicted with a beautiful stark austerity, almost in the way early photographers documented the natural landscape. An exhibition at the International Museum of Photography in Rochester, New York featuring these photographers also revealed the growing unease about how the natural landscape was being eroded by industrial development.