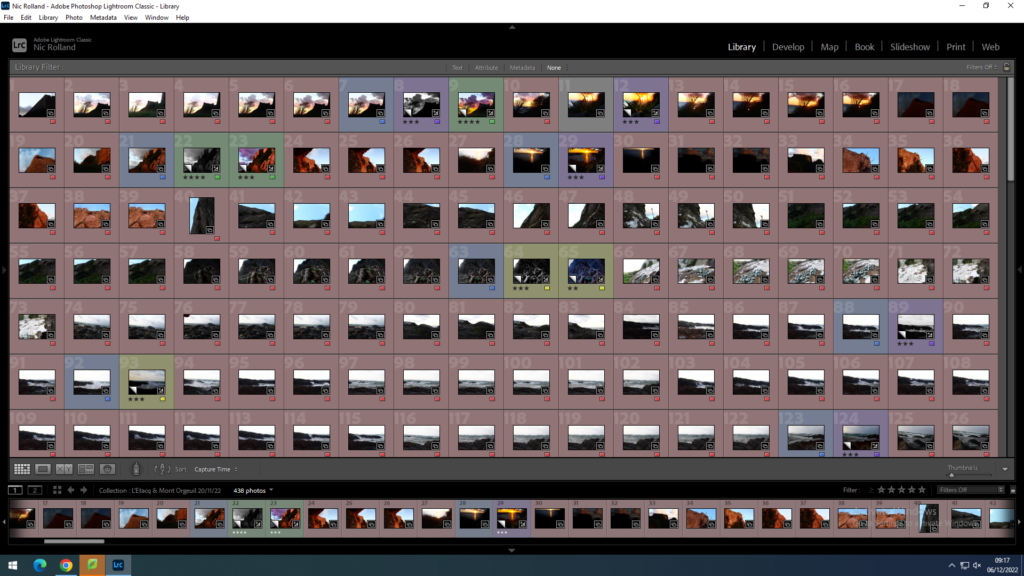

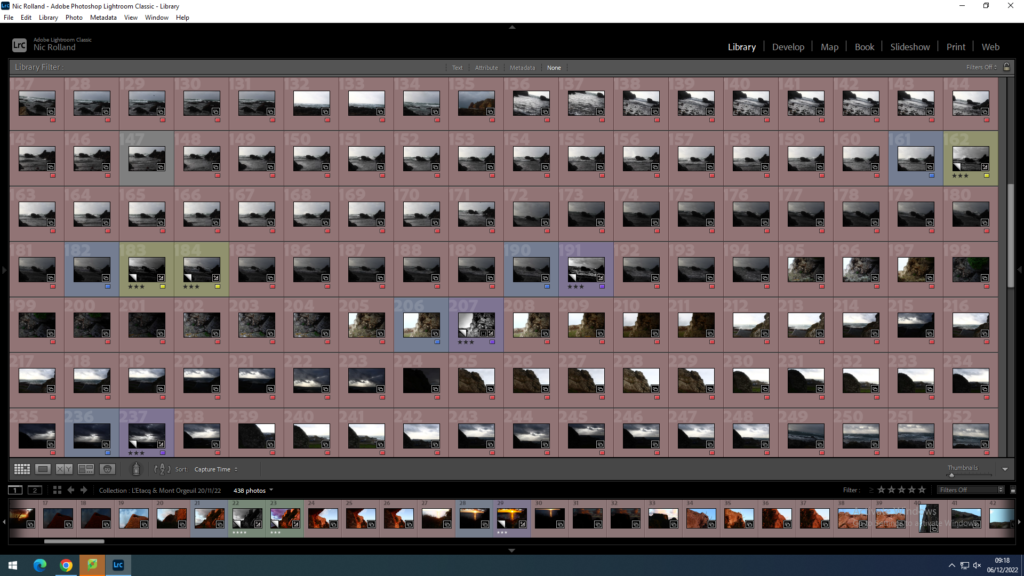

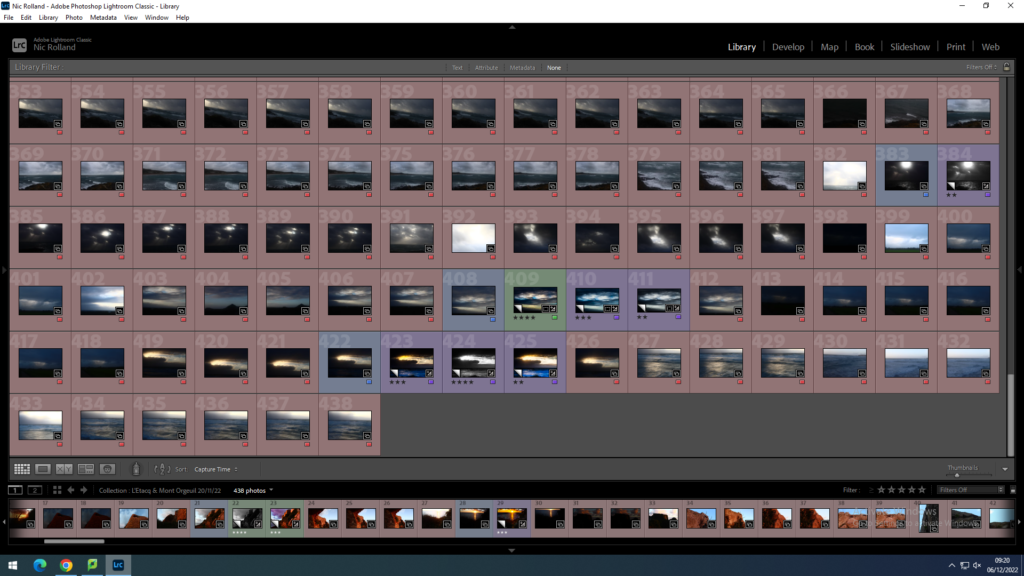

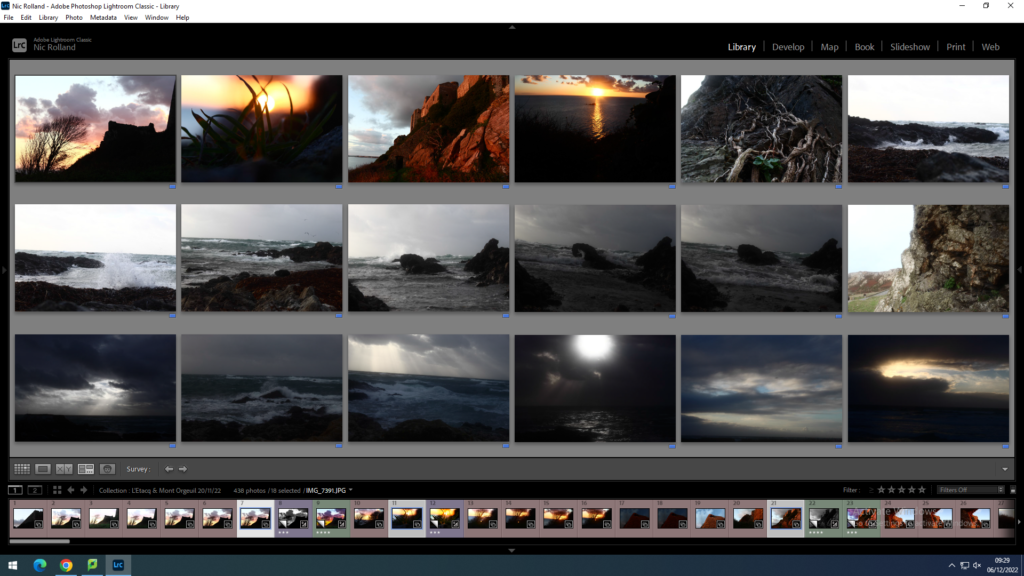

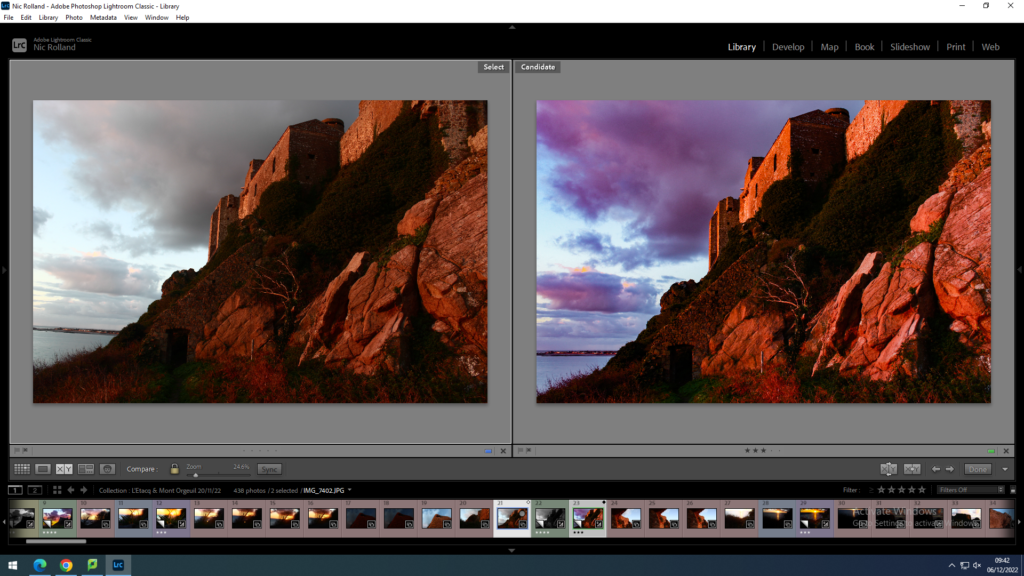

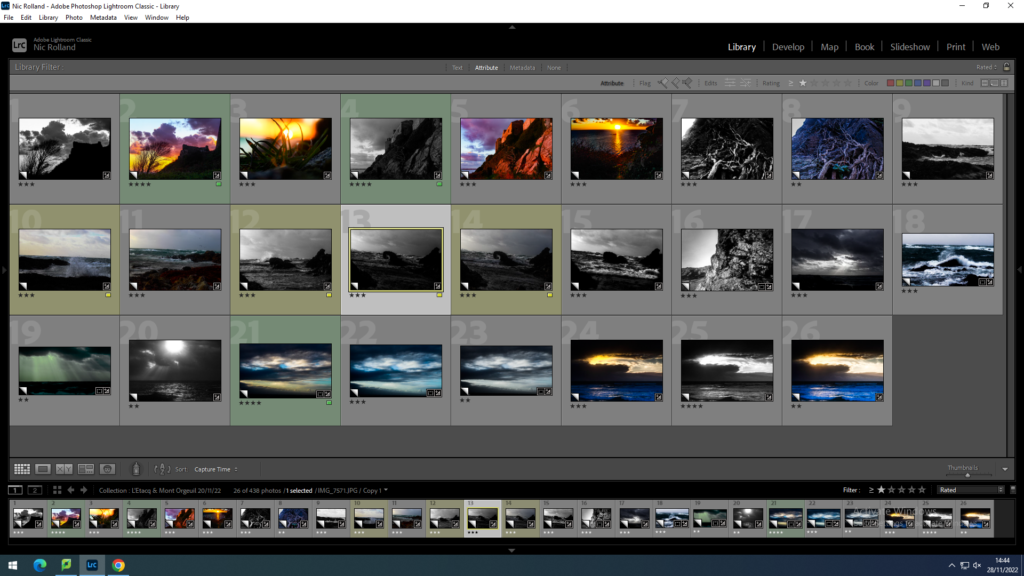

These are the best edits from my first Landscape Photoshoot focusing on the coastlines and and cliffs of Jersey

My favourite image is “Sunrise at Jersey”, which uses a multitude of colours, an unperceived array of shades not usually associated with a sunrise. The photo contains the typical yellows and oranges, but then the large clouds in the background almost absorb those colours and make the blues and purples shown, creating this dark dramatic object stand out amongst the bright glow of the sun. The foreground breaks up the image a little bit by creating a slight silhouette closer to the bright, fiery aspects, but further away and closer to the ground, you can begin to see the greens and browns of the undergrowth. The lighting within the image is natural sunlight located behind Mont Orgeuil Castle. The light within the sky greatly contrasts that in the foreground and seems well exposed. However, the foreground of the bushes and castle ruins in the image is slightly under exposed and I could have used exposure bracketing to keep the sky the way it was but clearly show what my eye saw with the bushes and trees being well lit rather than seeming like a failed silhouette as shown in the image. I used a 55mm lens when taking the photograph with a wide aperture of f/5.6. The shutter speed was 1/50 sec, disallowing an overexposed sky compared to a well exposed foreground. The ISO was kept at ISO 100. The space of the image seems quite separated, the sky in the background visually looks very distant from the foreground however the foreground creates this very abstract, 2D shape with curved and natural lines. The composition of the image creates allows the viewer to see the beauty of a sunrise that most don’t tend to see. The brightness of the sun surrounded by the dark foreground and clouds in the sky draw the eye to the centre of the image creating a sense of awe from the great contrast of the framing surroundings. The image shows the ruins of part of Mont Orgueil castle, a site with a history spanning over 800 years. During this time, it has been subject to medieval conquests and sieges from the French, the Nazi occupation and the harsh weathers throughout the past 8 centuries. But the one thing that has never changed was the sunrise. This is what I wanted to capture when taking the image. The links between this great feat of human construction suffering to the punishment of time but still having that slight protection of plants and trees, almost strengthening its defences against the elements.