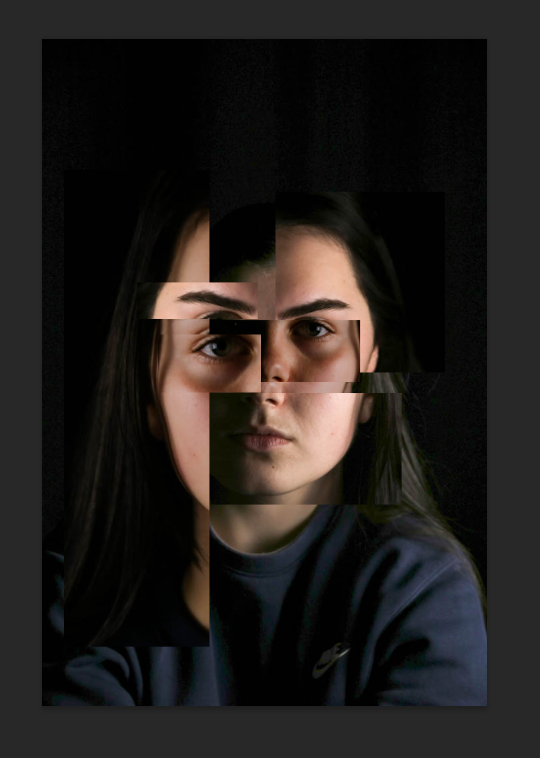

Where it all started…

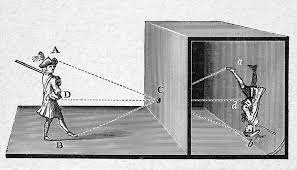

Camera obscura & pinhole photography

“Maybe the only thing each of us can see is our own shadow. Carl Jung called this his shadow work. He said we never see others.

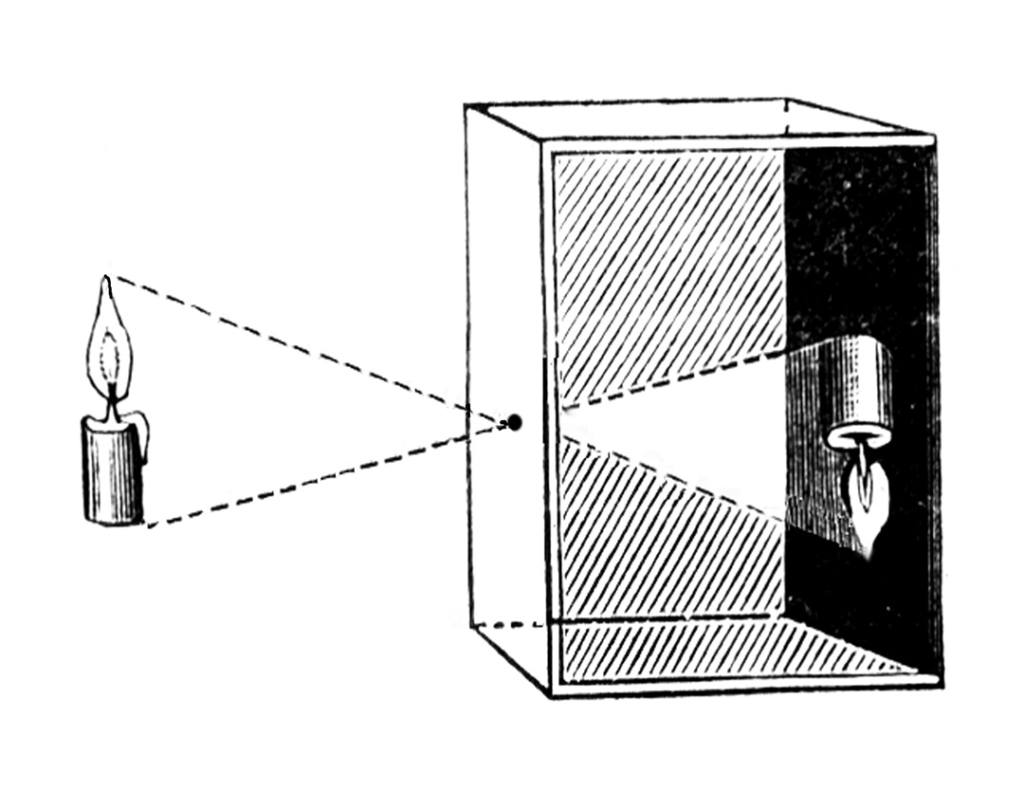

A camera Obsucra is a darkened room with a small hole or lens at one side through which an image is projected onto a wall or table opposite the hole.

Camera obscura can also refer to analogous constructions such as a box or tent in which an exterior image is projected inside. Camera obscuras with a lens in the opening have been used since the second half of the 16th century and became popular as aids for drawing and painting. The concept was developed further into the photographic camera in the first half of the 19th century, when camera obscura boxes were used to expose light-sensitive materials to the projected image.

Rays of light travel in straight lines and change when they are reflected and partly absorbed by an object, retaining information about the color and brightness of the surface of that object.

Lighted objects reflect rays of light in all directions. A small enough opening in a barrier admits only the rays that travel directly from different points in the scene on the other side, and these rays form an image of that scene where they reach a surface opposite from the opening. The human eye (and those of animals such as birds, fish, reptiles etc.) works much like a camera obscura with an opening (pupil), a convex lens, and a surface where the image is formed (retina). Some cameras obscura use a concave mirror for a focusing effect similar to a convex lens.

Pinhole photography

A pinhole camera is a simple camera without a lens but with a tiny aperture —effectively a light-proof box with a small hole in one side. Light from a scene passes through the aperture and projects an inverted image on the opposite side of the box, which is known as the camera obscura effect. It is similar to camera Obsucra in the way that the camera is re-enacting the concept that an image is produced by light coming through a small hole projecting the image onto a dark area. same concept different perspectives.

Nicephore Niepce and Heliography

Joseph Nicephore Niepce was a French photographer (1765- 1833). He was one of the most important figures in the invention of photography, in 1807, together with his brother, Claude, he invented the world’s first internal combustion engine, which they called the pyreolophore.

Letters to his sister-in-law around 1816 indicate that Niépce had managed to capture small camera images on paper coated with silver chloride, making him apparently the first to have any success at all in such an attempt, but the results were negatives, dark where they should be light and vice versa, and he could find no way to stop them from darkening all over when brought into the light for viewing.

Niépce’s correspondence with his brother Claude has preserved the fact that his first real success in using bitumen to create a permanent photograph of the image in a camera obscura came in 1824. That photograph, made on the surface of a lithographic stone, was later effaced. In 1826 or 1827 he again photographed the same scene, the view from a window in his house, on a sheet of bitumen-coated pewter. The result has survived and is now the oldest known camera photograph still in existence. The historic image had seemingly been lost early in the 20th century, but photography historians Helmut and Alison Gernsheim succeeded in tracking it down in 1952. The exposure time required to make it is usually said to have been eight or nine hours, but that is a mid-20th century assumption based largely on the fact that the sun lights the buildings on opposite sides, as if from an arc across the sky, indicating an essentially day-long exposure. A later researcher who used Niépce’s notes and historically correct materials to recreate his processes found that in fact several days of exposure in the camera were needed to adequately capture such an image on a bitumen-coated plate.

Heliography is this process Joseph had made, it is still used today mainlt for photo engraving.

Louis Daguerre & Daguerreotype

Key facts:

- French artist and photographer

- invention of the daguerreotype process of photography

- worked closely with Joseph Niepce

- an accomplished painter

- developer of the diorama theatre.

What is the process daguerreotype?

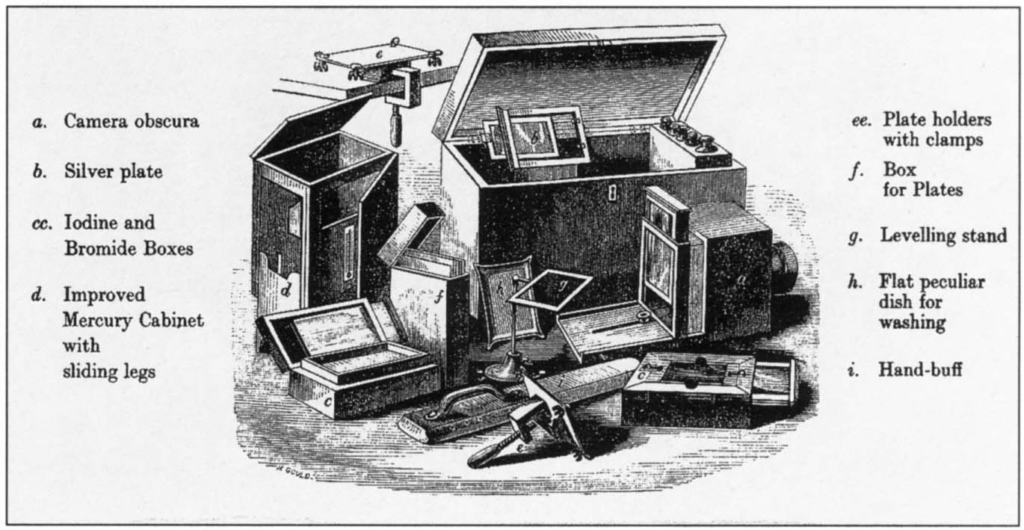

The daguerreotype is a direct-positive process, creating a highly detailed image on a sheet of copper plated with a thin coat of silver without the use of a negative. The process required great care. The silver-plated copper plate had first to be cleaned and polished until the surface looked like a mirror.

The earliest cameras used in the daguerreotype process were made by opticians and instrument makers, or sometimes even by the photographers themselves. The most popular cameras utilized a sliding-box design. The lens was placed in the front box. A second, slightly smaller box, slid into the back of the larger box. The focus was controlled by sliding the rear box forward or backwards. A laterally reversed image would be obtained unless the camera was fitted with a mirror or prism to correct this effect. When the sensitized plate was placed in the camera, the lens cap would be removed to start the exposure.

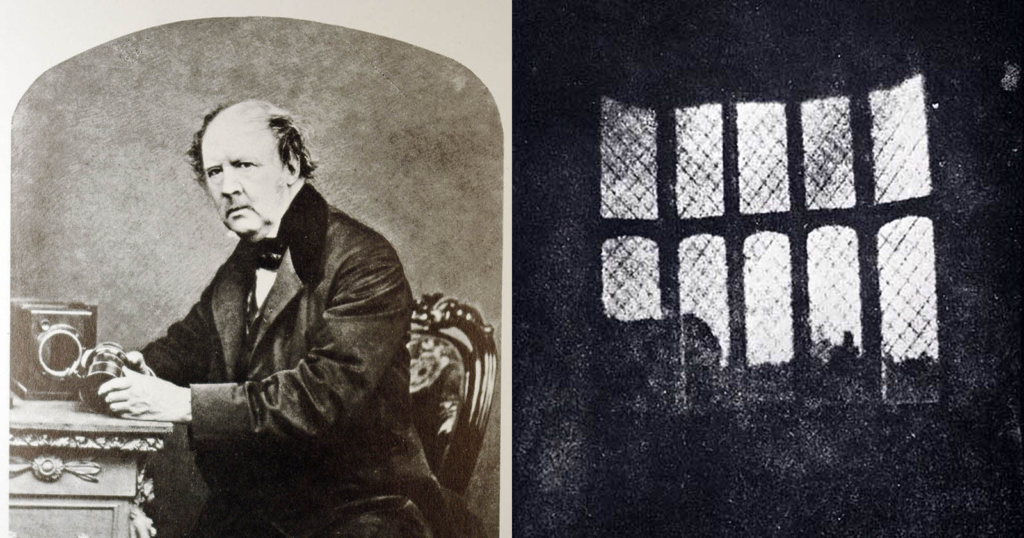

Henry Fox Talbot & Calotype

Henry fox developed three primary elements of photography:

- developing

- fixing

- printing

He learnt that creating an image would require extremely long exposure times. he continued to accidently discover that there was an image after a shirt exposure time, although, it wasn’t visible he learned that chemically develop it into a useful negative.

With the negative image, Fox Talbot realised he could repeat the process of printing from the negative. Consequently, his process could make any number of positive prints, unlike the Daguerreotypes. He called this the ‘calotype’ and patented the process in 1841.

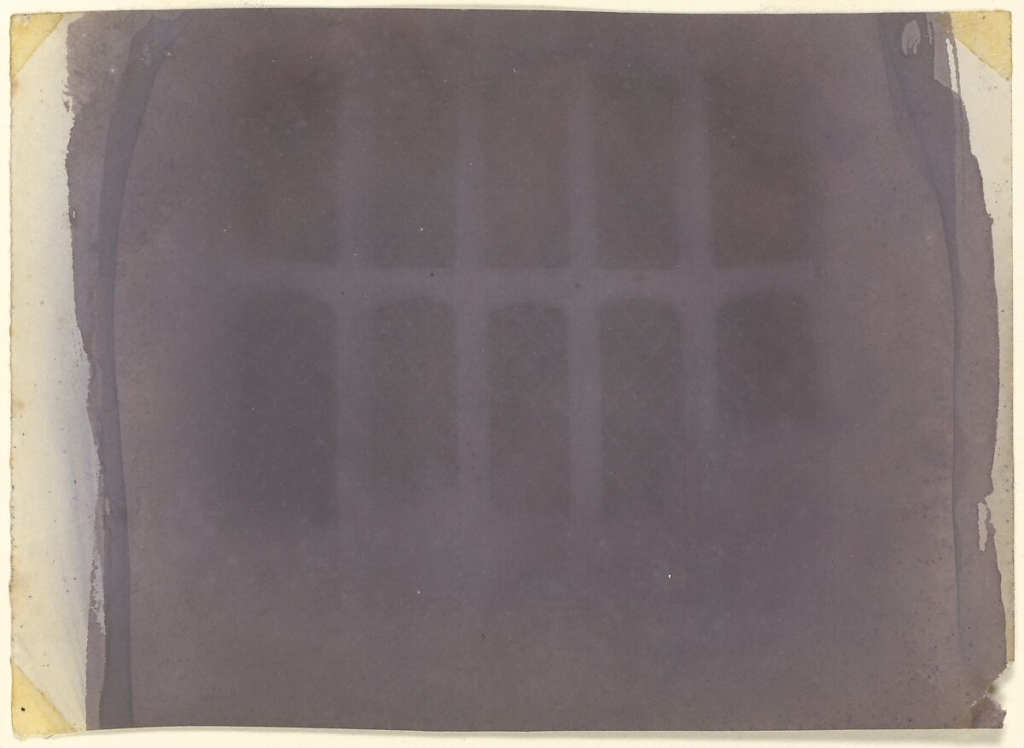

This mysterious view through the diamond-paned oriel window of Talbot’s home is one of the earliest photographs in existence—a remarkable relic of the inventor’s earliest attempts to make pictures solely through the action of light and chemicals. He brushed a piece of writing paper with salt and silver nitrate and placed it in a small wooden camera stationed on a mantel opposite the window for an exposure that may have lasted hours. The image is tonally reversed—a negative, though the term did not yet exist—as the paper darkened most where it recorded the bright light of the windows.

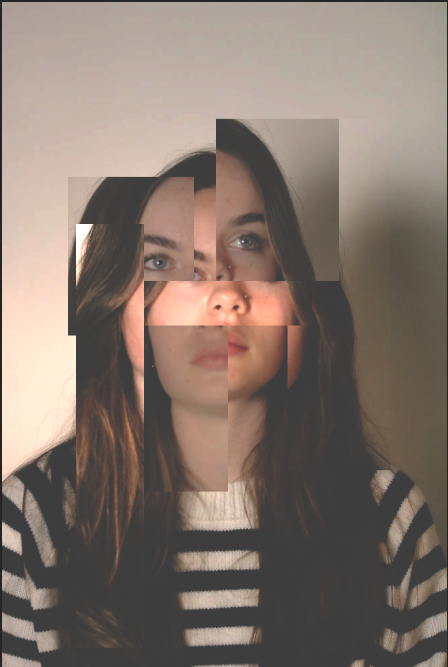

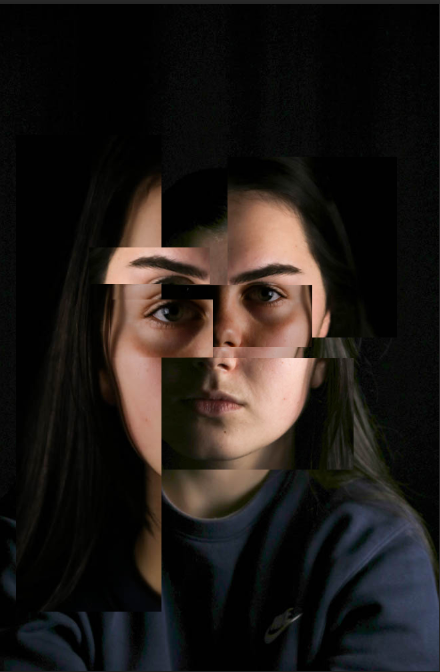

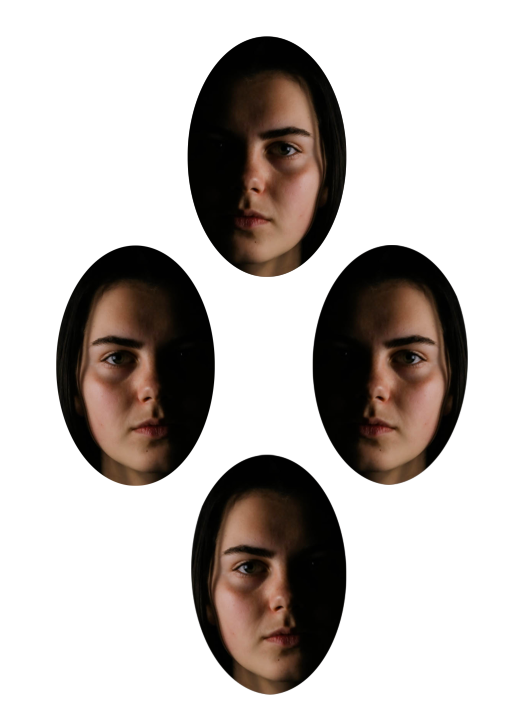

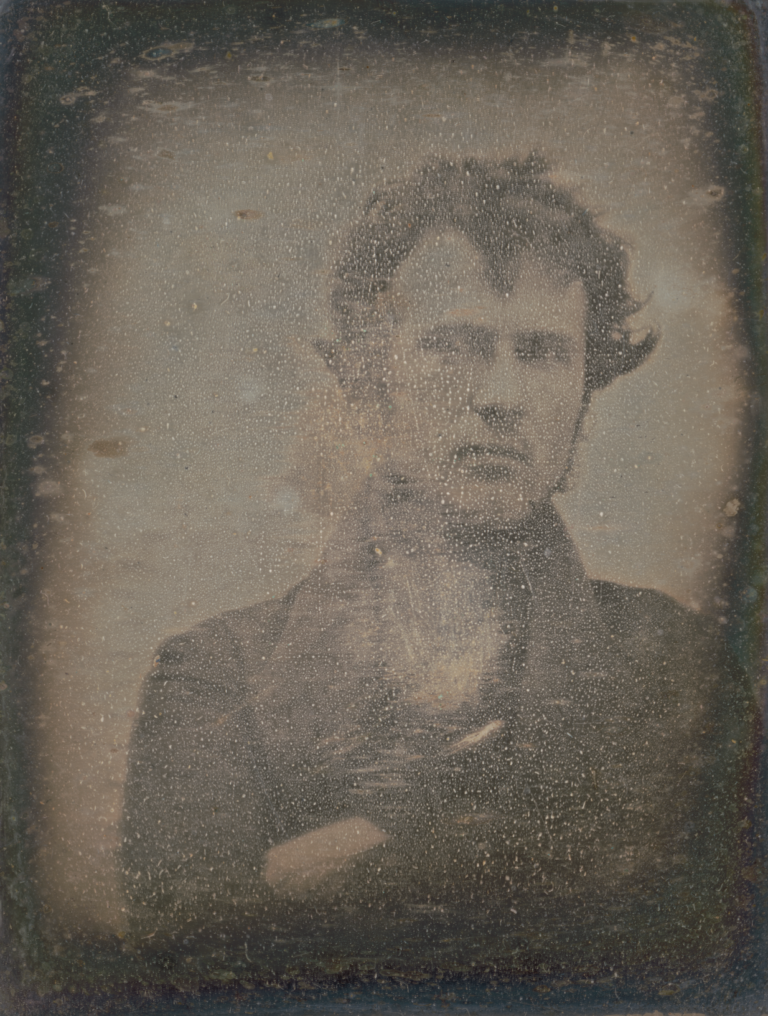

Robert Cornelius & self-portraiture

“Taking a self-portrait is a whole next level up from that. That portrait is incredibly significant.”

In February 2014 a daguerreotype self-portrait taken by the American photography pioneer Robert Cornelius of Philadelphia was considered the first American photographic portrait of a human ever produced, and since this was a self-portrait, it was also possibly the first “selfie .” This was a major change in photography, later on enabling how advanced our photography is now.

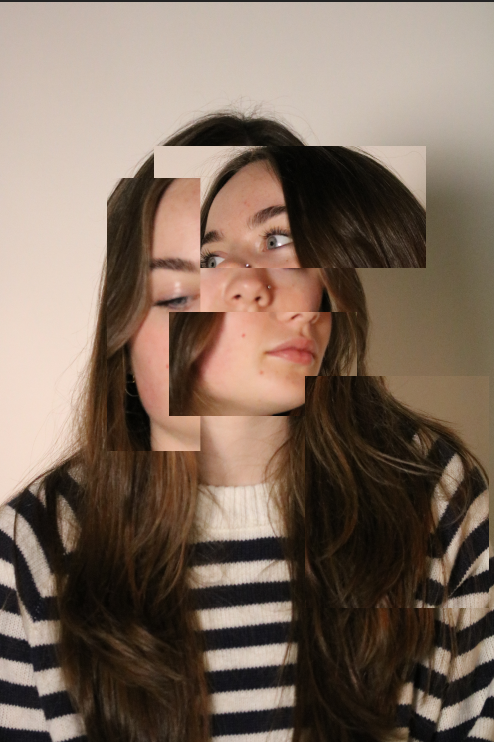

Julia Margeret Cameron & Pictorialism

Julia had a different take on portraits and is known for her soft focus close ups of famous Victorian men. Working around mythology, Christianity, and literature.

Cameron included imperfections in her photographs – streaks, swirls and even fingerprints – that other photographers would have rejected as technical flaws. Although criticised at the time, these imperfections can now be appreciated as ahead of their time. In her work Iolande and Floss, for example, swirls of collodion used during the photographic process merge with the swirls of drapery, enhancing the dreamy, ethereal quality of the image.

We don’t know if Cameron herself embraced these ‘flaws’ or if she simply tolerated them. We do know, however, that she sometimes scratched into her negatives to make corrections; printed from broken or damaged negatives and occasionally used multiple negatives to form a single picture, which tells us that she didn’t mind a certain level of visible imperfection, at the very least.

One of her most extreme examples of manipulating a negative can be seen in a portrait of Julia Jackson. Cameron scratched a picture into the background of this pious portrait of her niece, to create a hybrid photograph-drawing. The drawing of a draped figure in an architectural setting evokes religious art.

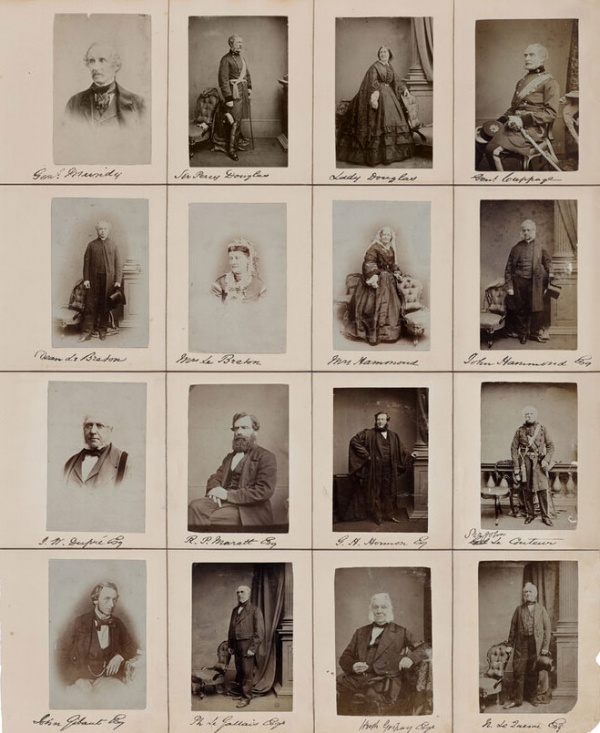

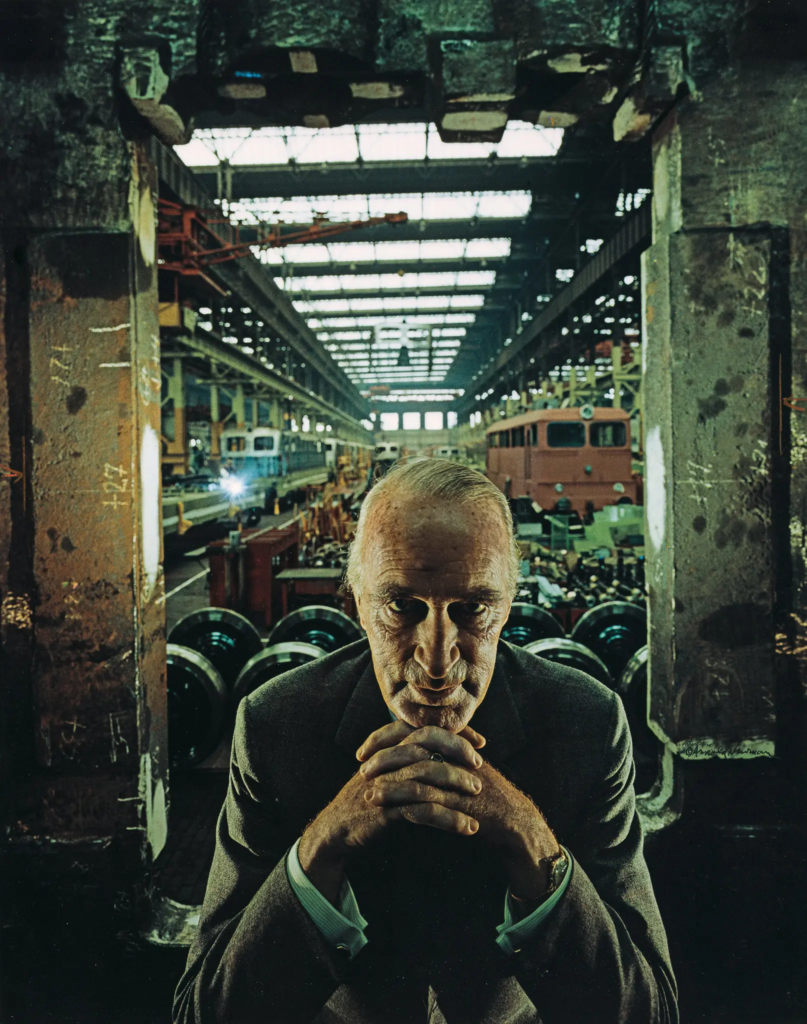

Henry Mullins & Carte-de-Visit

Henry Mullins made over 9000 carte de visite portraits of Jersey’s ruling elite and wealthy upper classes.

Henry Mullins – Michelle Sank – on the social matrix

Henry Mullins / Michelle Sank on the social matrix, a juxtaposition is created by the editors between the historical photographs of Henry Mullins that date to the 1860’s, with the recent portraits by Michelle Sank. At first blush this book appears to highlight the differences of the passing of 160 years in photography; warm toned black and white photographs created by wet collodion on glass with that of contemporary color. The stilted poses required for the longer colloidal exposures versus the fluidity of the current instant moment.