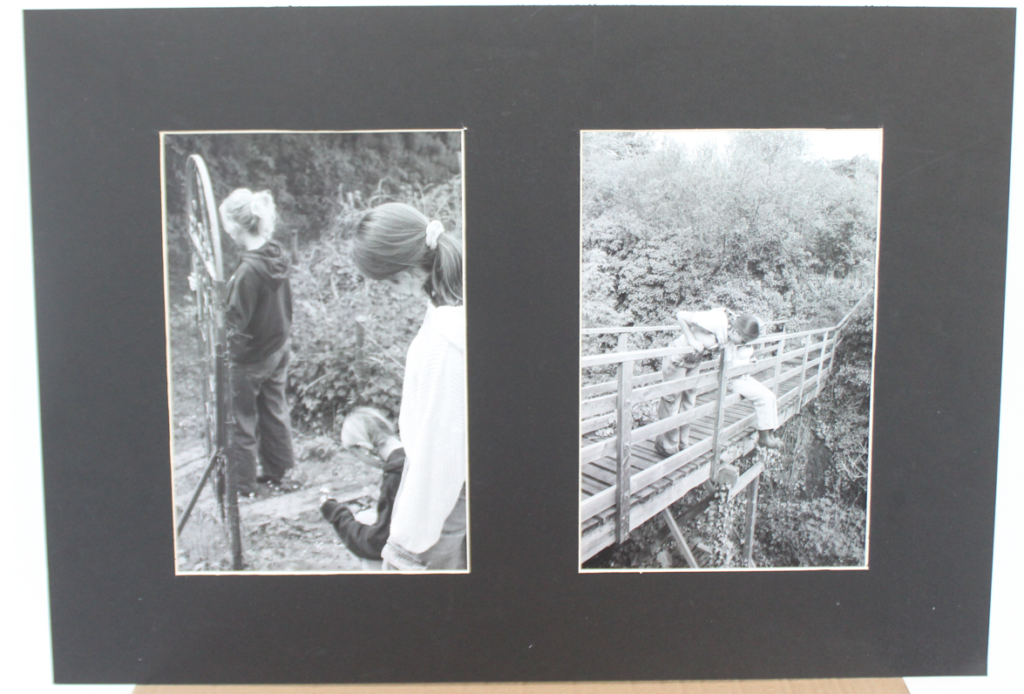

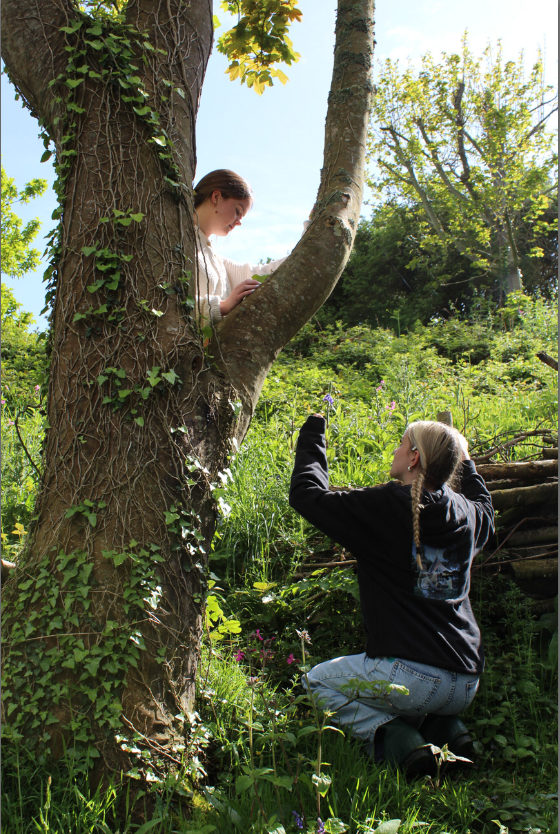

Justine Kurland – ‘female utopia’

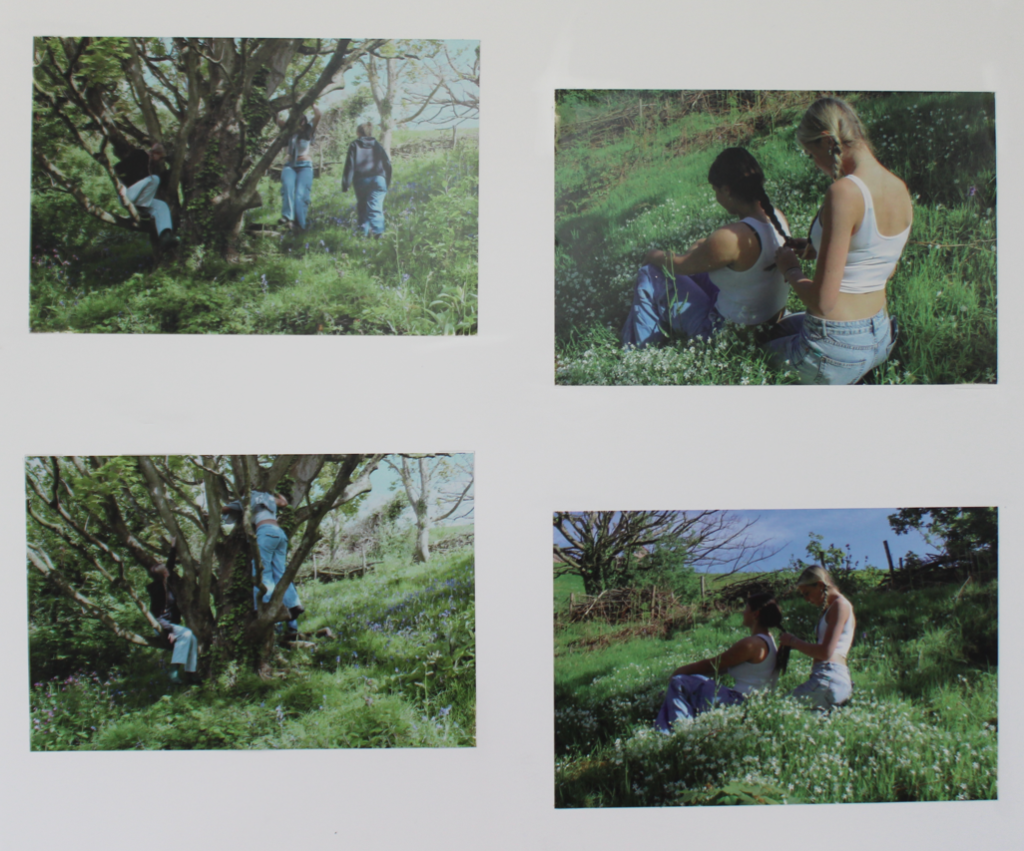

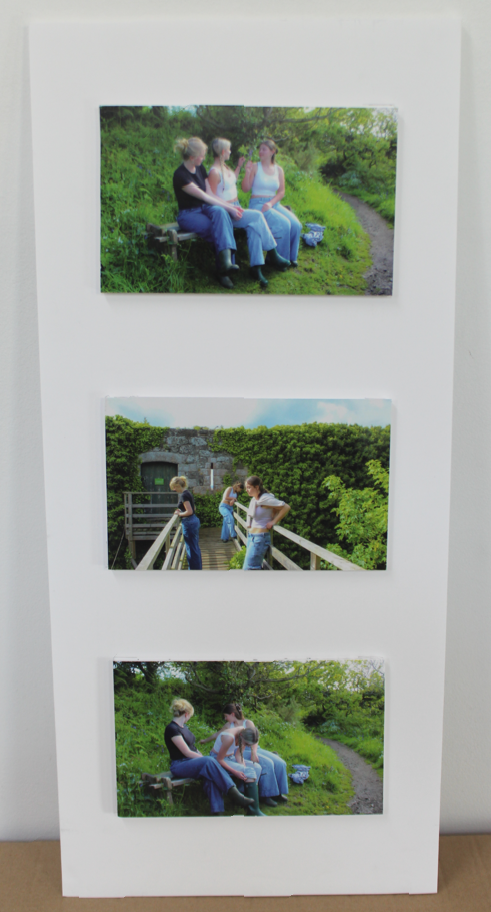

My main inspiration is from her book called ‘girl pictures’ its exactly what I wanted to base my photoshoot on and how id like to represent femininity. It shows girls coming together and the simplistic caring traits that are shown.

About Justine’s book/photography:

Kurland started this project in 1997 when she was a graduate student at Yale. In an essay at the back of the book, she crowns Alyssum as “the first girl” to be photographed. It started as a kind of make-believe. At fifteen Alyssum had been sent to live with her dad, whom Kurland was dating at the time. While he was at work, the two women bonded and began a collaboration, merging imaginations to plot out a narrative of a teenage runaway. Kurland went on to find more make-believe runaways, but one of the images from this time seems to hold a special importance; a portrait of Alyssum takes up a full spread towards the end of the book. Perched in a cherry tree between the Hudson river and a highway, Alyssum looks back over her shoulder. The river seems to flow away, while the headlights of cars on the road seem to be approaching. With her body in profile, Alyssum doesn’t seem to follow either direction.

Analysing some of Justine’s images:

Adventure stories were a source of inspiration for this project. The girls in Girl Pictures plagiarize these myths until they become their own, until the original myth is hardly relevant anymore. What’s left after all this repetition of runaway legends and costumes are the common themes: rebellion, self-sufficiency, confidence. A kind of inverse of the American Dream, but with the same carrot on a string: freedom. Perhaps this is why we love runaways so much.

We see worn out overalls holding onto a girl’s body by one strap. The girl at the centre of this image guides the others, looking past the camera as if it doesn’t even matter, as if the thing worth examining is actually behind us.

But of course with freedom comes the threat of danger. So many of the images in Girl Pictures were taken outside in locations that feel desolate or easy to overlook. They are often staged under bridges or beyond fences or on the sides of highways; places that feel synonymous with warnings.

The focal point of the image is the back of a young girl who is raising her shirt. Instead of her face, we see the eyes of all the girls surrounding her, watching the big reveal. There’s one boy in the group, but his eyes are covered. A girl has wrapped her arms around him from behind and places her fingers over each of his eyes. It’s funny to see such an obvious removal of the male gaze, especially as it’s still present – and yet the delicate hands of a teenage girl prove capable of obstructing it. As viewers we look from his covered eyes to her watchful ones.

Yet it feels beside the point to spend too much time considering a male perspective when looking at this project. The subjects move on, and do more interesting things. They collapse in the snow in ‘Snow Angels, 2000’, and roast marshmallows over a garbage fire in ‘Puppy Love, Fire, 1999’. It starts to feel as if they exist in their own reality, just removed enough. This is especially strong in the photographs that appear to capture two parallel worlds.

There are other things uniting all the girls in these photographs. The deeper you get into the book, the more difficult it becomes to see each girl as a distinct character. The camera stays just far enough away to keep the subjects slightly anonymous. Or perhaps it’s because they are mostly long haired, or wearing similar clothing, or belonging to that vague age range that captures adolescence. Whatever it is, they begin to blend together into one visually unified group of girls.

Kurland’s focus is less on individual girls, and more on what happens when they band together.

I found this text on a website and i agree with how i perceive the book and the idea of how girls specifically teenage girls are represented:

‘I don’t know any of the girls in Justine Kurland’s Girl Pictures, but it really feels like I do. Or at least, I must have seen them. Maybe they were there on the side of the highway, or in some public restroom, or just standing on a sidewalk as I passed by. The girls in their baggy jeans and bare feet. The girls in their leather boots and used sweaters. There’s something about them that feels like so many teenage girls. The images in this book weigh me down with a sense of nostalgia, and it’s not just the late nineties fashion. It’s the fact that the girls seem to be disappearing. Like catching a wild animal in a trap, it feels like by the time you look at each image of these girls you’ve already missed them. They’ve run off to someplace better or just some place that isn’t here.’

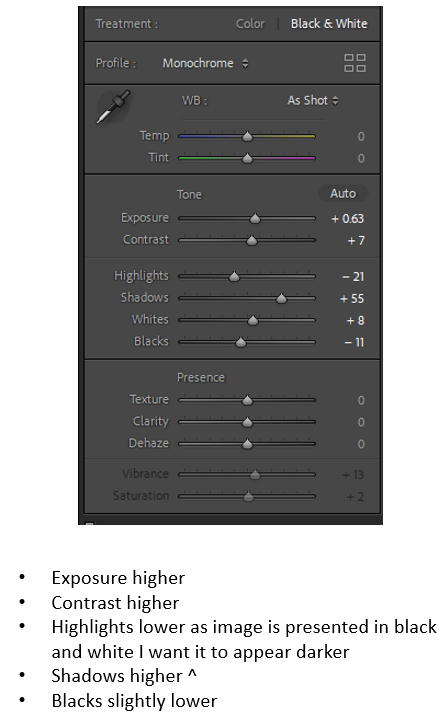

Using this book as a reference I’ve found that it creates an emotional connection and deeper meaning.