In what ways have Rejlander and Shonibare explored narrative in their photography?

“The use of actors, assistants and technicians needed to create a photographic tableau redefines the photographer as the orchestrator of a cast and crew, the key rather than sole producer.”

David Bate (2016), ‘Art Photography’. London: Tate Galleries

INTRODUCTION

Stories and tales have been told in various ways for millennia, from word of mouth, to the page; from stage to camera. The pictorialist movement and tableau vivant photography are key styles for this topic where, as David Bate puts it, the photographer is redefined as the ‘orchestrator of a cast and crew’ becoming the ‘key’. This suggests that the photographic process in tableau image making matches that of creating scenes on the stage. If we take a generic proscenium arch theatre to create the frame for our image, a director must understand the relationship between what is within the frame, the audiences ideal reaction and what occurs behind the scenes simultaneously; when these aspects are translated into a photography studio, a direct link between the two disciplines is displayed. Tableau imagery historically began on the stage and conveys a single narrative through a series of still images created by extensive theatrical groups. This style of performance found its way into the photographic medium and heavily influenced the works of Oscar Gustave Rejlander and Yinka Shonibare. These two artists explore narrative in similar ways to each other, establishing links to the traditional . The ideas behind narrative photography are to reveal a story in one single image. It compresses an entire story within a single frame and removes the ideas of typology, documentary, and film.

TABLEAUX + TABLEAU VIVANT

Directly translated from French to ‘living picture’, tableau vivant displays one or more actors, often fully equipped with costume, set and props to create a frozen image combining theatre and the visual arts. On stage the style began 300 BCE by the Greeks at their festivals worshiping the Gods. They could tell elaborate stories from still but large and accentuated positions that allowed the tale to be seen from hundreds of meters away. Tableau vivant was also loved in the middle ages before the Tudors brought about Shakespeare and Georgians adoring opera and commedia dell’arte. When the Pictorialist movement established ideas that photography was an art form and not simply a scientific tool, tableau vivant was restored to theatres in the late 19th Century when photography was being seen as an art form and not just a scientific practice of documentation.

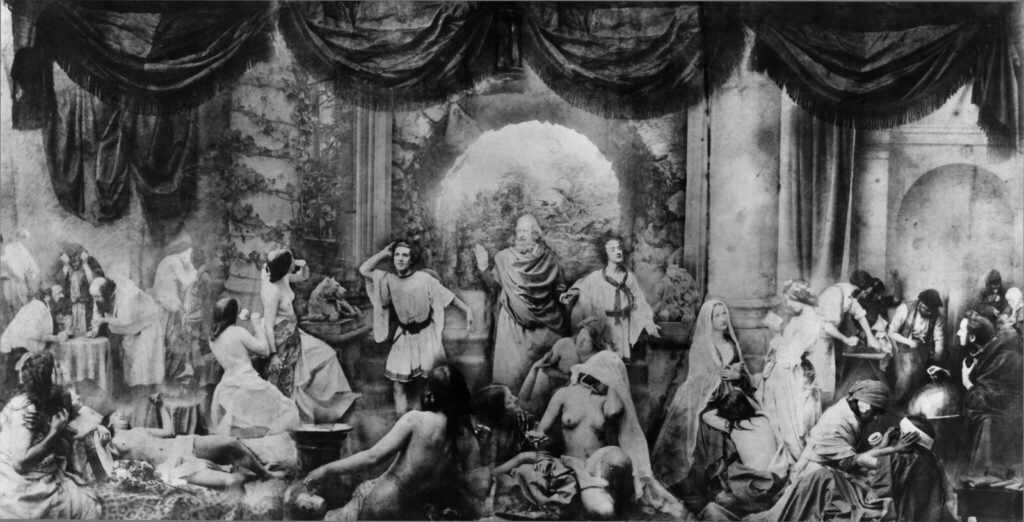

Today we recognise tableau imagery as being a possible basis for works created by Rejlander and Shonibare; where a single image holds an entire narrative. Rejlander took on the approach of a tableau director where each aspect of the performance must be decided and controlled by a single person so that every inch of the performance adds to the story and the final outcome of the display. When creating ‘Two Ways of Life’ in 1857, Rejlander took 30 negatives and combined them to create a single large combination print that showed the scene on stage as elaborately detailed as the cameras of the time would allow. More recently, Yinka Shonibare used a similar style of tableau imagery when creating his series ‘Diary of a Victorian Dandy’. Each photograph displayed different aspects of ‘a day in the life’ of a rich man from the Victorian era but changed the specifics of racial discrepancies so that the British-Nigerian artist starred as the ‘Victorian Dandy’ for each image. His series clearly displayed the intricacies of tableaux vivants that I believe allow the exploration of narrative in both of these artists’ works.

OSCAR GUSTAVE REJLANDER – ‘Two Ways of Life’

Oscar Gustave Rejlander’s ‘Two Ways of Life’ was one of the most ambitious and controversial photographs of the nineteenth century. It was an elaborate allegory of the choice between vice and virtue, represented by a bearded sage leading two young men from the countryside onto the stage of life. Because it would have been impossible to capture a scene of such extravagant complexity in a single exposure, Rejlander photographed each model and background section separately, combining them to create an innovative and complex print that pioneered the world of combination printing.

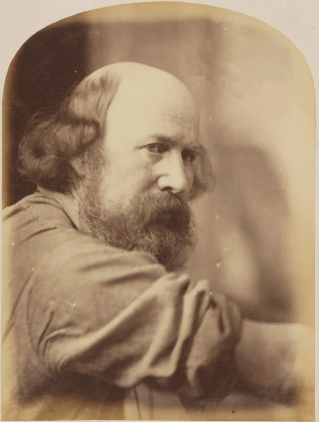

Rejlander was first known as a painter and lithographer, studying art and antiquity in Rome before exhibiting his paintings the Royal Academy, England in 1848. He later learned photography from Nicholas Henneman in 1853 and just four years later created and displayed his ‘Two Ways of Life’ at the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition and at the Photographic Society of London. The narrative behind this image explores the allegorical choice between vice and virtue where a bearded sage (played by Rejlander himself) leads to young men to the choices. One rushes to the pastime of drinking and gambling while the other seems to glide to the virtues of marriage and religion. The narrative displays the allegory of choosing the right path in life.

The image became one of the most controversial of the time with the semi-dressed women on the Left of the photograph. Rejlander was open to criticism from Victorian society and the image was first refused by the Photographic Society of Scotland and later displayed there with the left side hidden by a sheet. The two sides of the image both displaying the opposites of one another reflect the biblical ideas of the right to be righteous and the path of God while the left is seen as the side of the devil. Society had always deemed that left-handed people were the spawns of the devil and with the ideas of Left and Right Wing politics on the verge of existence within Europe, Britain was most definitely on the Right and therefore, in line with the ideas that Rejlander’s image presents, is righteous and Godly.

Rejlander sees his work within the narrative style as a way of expressing his thoughts and feelings through images. He said:

“I regard art as a means of making thought visible. If I can make a thought visible in a picture which people can understand, and be moved by it to laughter or tears, it is a work of art whether I produce it by the aid of a camera or of the pencil. It is the mind of the artist, and not the nature of his materials, which makes his production a work of art.”

This idea that Rejlander follows allows the narrative of the image itself to display the clarity and detail required to allow people to understand exactly the artists intended message for the piece. The single image that he produced creates this complex fable that uses the ideals of religion and biblical understanding to connect with its audience. Every aspect of the image has been meticulously arranged and coincides directly with the style of tableau vivant. The formatting of the image, the poses that each actor performs, and the scenes within the frame outline the full story within the single image, clearly displaying Rejlander’s interpretation of the narrative style in photography.

YINKA SHONIBARE – ‘Diary of a Victorian Dandy’

“I realised … that I didn’t have to be painting on canvas to be an artist. Painting is so historically loaded, anyway – it’s like a sign of white male dominance.” (Yinka Shonibare, 2020)

Shonibare’s modern works illustrate ideas of narrative and tableaux imagery, allowing more intense messages to be conveyed. He attempts to examine race, class and the construction of cultural identity in all of his works, but a prominent example of this would be his series ‘Diary of a Victorian Dandy’, showing the artist himself a ‘pretentious, status conscious figure who seeks acceptance in aristocratic milieu.’ (Museum, V. and A. 2013) Being British-Nigerian, Shonibare has dealt with racism throughout his life and engages with his “‘outsider’ status as a black, disabled artist” investigating the conditions of postcolonialism and globalisation.

The image above, titled ‘Diary of a Victorian Dandy: 14.00 hours’ shows the artist as a single black man in a room filled with white businessmen and servants. Put into historical context, the artist is the single figure that seems out of place and puts to question why has the artist decided to build a narrative with a stereotypical and historical title, then present the opposite of what audiences would expect to see in the series. In accordance to his artistic aims for the series, it is a clear commentary on colonialism and the tangled interrelationship between Africa and Europe. I believe the fact that all but Shonibare seem to have eccentric expressions with their characters which comments on the racial oppression faced by many African’s taken by Europeans as slaves to the Americas. Shonibare’s lack of expression suggests that although he is depicted as the well-loved gentleman in the room, he still feels that racial differences prevent him from enjoying this high position. The series is a clear reflection of British heritage and forces its audiences to understand that despite the progression of society to the acceptance of one another, nothing can change the impact that the past has on our lives today.

The way in which Shonibare explores narrative matches techniques used by Rejlander in creating his ‘Two Ways of Life’ but solely by the usage of tableaux. Shonibare chose to create five images that told one story as opposed to Rejlander’s singular outcome. Rejlander composes a single scene where every aspect is choreographed; Shonibare takes this further, following the traditions of tableau vivant where multiple frozen scenes (each meticulously planned and positioned) combine to tell the overall narrative.

CONCLUSION

Rejlander and Shonibare have both created their own responses that differ greatly from one another when exploring narrative in their imagery. Rejlander has utilised the well-loved theatrical style of tableau vivant, “posing their models in allegorical arrangements that addressed such themes as childhood, the virtues of motherhood, and the beauty of nature” (Thomas, A. London: Merrell Publishers); solidifying a theatrical style as well as a story within a single image. Shonibare’s work uses historical oppression and reverses it to create an intricate retelling of history, his way. Both use a clear basis, a story that already exists, and either employed ideas provided by society or moulded them to establish their own comments on the world. Either artist can be considered a pioneer in their artistic careers, perhaps not for the same reasons, but they most definitely created works that had a profound impact on the way we look at the world, achieving every artists ambitions: to influence their audience to think about their own lives and their positions in the world.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Thomas, A. (2006) ‘Modernity and the Staged Photograph, 1900-1965’, In: Pauli, L. (2006), Acting the part: Photography as theatre. London: Merrell Publishers, pp. 102–108.

J. Paul Getty Museum (2019), Oscar Rejlander: Artist Photographer. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum

Museum, V. and A. (2013) Diary of a Victorian Dandy: 14.00 hours: Shonibare, Yinka: V&A explore the collections, Victoria and Albert Museum: Explore the Collections. Available at: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1263374/diary-of-a-victorian-dandy-photograph-shonibare-yinka/ (Accessed: 10 November 2023).

Bate, David (2016) ‘Once Upon a Time’ in Art Photography. London: Tate Galleries.

Reilly, S. (2020) ‘The Wit and Wisdom of Yinka Shonibare’, Apollo Magazine.