There are many theories of photography, ways of interpreting the meaning of photographs. When we say that it is important to be visually literate (or media literate or even photo literate) we mean that it is useful, in a world that is saturated by visual media, to have some tools with which to interrogate images of various sorts. When it comes to the essence of photographic images, the direct relationship between the photograph and the object photographed is reliant on the light that passes from one to the other. This is sometimes called an “indexical” relationship. The word comes from the American philosopher Charles Sanders Pierce whose work on semiotics (the study of signs and symbols and their use or interpretation) was first published in the 1930s. He identified three types of sign: indexical, iconic and symbolic. He referred to photographs as examples of indexical signs because of their direct physical relationship to the thing photographed.

The camera does more than just see the world; it is also touched by the world. Light bounces off an object or a body and into the camera, activating a light-sensitive [surface] and creating an image. Photographs are therefore designated as indexical signs, images produced as a consequence of being directly affected by the objects to which they refer. It is as if those objects reached out and impressed themselves on the physical surface of the photograph, leaving their visual imprint…

— Geoffrey Batchen, photo-historian

Of course, not all photographs represent objects as they look to our eyes. Writers like Susan Sontag and André Bazin recognise that, despite various kinds of distortion (out of focus, discoloured etc.) all photographs offer a kind of proof that something happened. Other writers prefer the word “trace” to describe how photographs work. Alan Trachtenberg, for example, uses the example of a shadow and a footstep as an analogy for photographs. A shadow is an indexical sign, directly related to the object and the light. A footstep, however, is an “iconic” sign that resembles its object but does not have a material connection to it. It is the trace of a human presence having left a mark on the land. A drawing of a person has a similar relationship. It is also a trace.

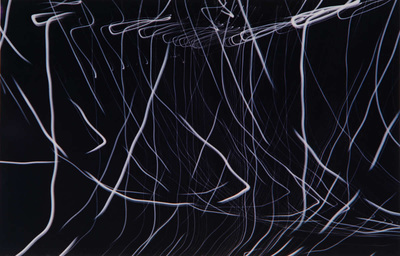

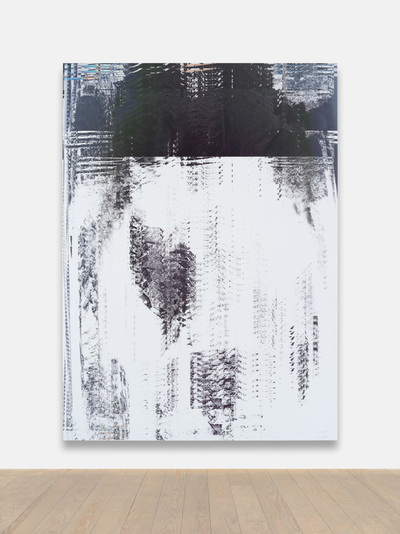

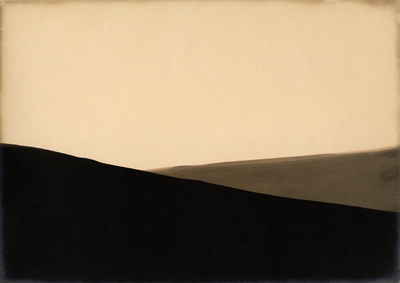

Take a look at these photographs. Think about them in terms of the directness of their relationship to the things photographed. How do these images capture light and how does this affect our relationship to them?

What is a photograph?

This question cuts to the heart of the matter. There have been numerous attempts to define photography once and for all but these have inevitably either neglected peculiar examples or been superseded by developments in practice. Perhaps it’s only possible to assert that the one common denominator of all photographs is that they rely on radiant energy (light, x-rays, gamma rays or cosmic rays) for their existence. As we have seen, a camera is most definitely optional. Much more than this is difficult to to say.

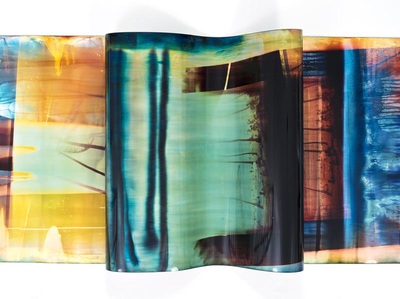

In 2014, the International Centre for Photography in New York held an exhibition with the title ‘What is a Photograph?‘. The exhibition explored experimental photography since the 1970s, including artists who have “reconsidered and reinvented the role of light, colour, composition, materiality, and the subject in the art of photography”. These experiments are, in part, a response to the digital revolution and the role that digital technology now plays in photography. This has prompted a renewed interest in analogue photography and the hybrid creations generated when analogue and digital collide. Criticism of the show drew attention to backward-looking, fine arty-ness and abstraction of the images on display.

The show doesn’t answer the question [What is a photograph?]. Rather, it brings together works from the past four decades by 21 artists who have used photography to ponder photography, leaving viewers to figure it out for themselves […] Several artists are committed to the processes and materials of the nearly obsolete darkroom […] It’s a strangely blinkered and backward-looking show. Nearly all the work on view has more to do with photography’s past than with its possible future.

— Ken Johnson

Take a look at some of the work featured in the show. Follow the links to find out more about the artists/photographers. What do you think?

Writer Jacob King is also troubled by this kind of photography exhibition in which photographs are displayed as works of art, like paintings or sculptures:

the gap between the photographic “objects” on view here and the myriad ways that photographs exist and circulate today is almost comical. While the exhibition included a number of interesting works, a viewer could walk through the show without ever knowing that a photograph could be viewed on a cell phone, that it could exist as a digital file, that it could circulate on the internet, that it could be tagged, or even that it could frame and reproduce something which was once before the camera’s lens (let alone that it might exist in an application like Snapchat.)

Photography finds itself at a crossroads. As analogue processes become obsolete and photography culture becomes ever more digital, photographs themselves are becoming increasingly dematerialised and more technologically sophisticated. Digital photographs are computational images and their relationship to reality is more complex than that of photogram or black and white film negative. Photographs in the future may look very different to those of today. They may include much more information than simply the activity of radiant energy.

The revolutionary change in photography’s cultural presence wasn’t led by photographers, nor publishers or camera manufacturers but by telephone engineers, and this process will repeat as business grasps the opportunities offered by new technology to use visual imagery in extraordinary new ways, throwing us into new and wild territory. It’s happening already and we’ll see the impact again and again as new apps, products and services hit the market. We owe it to the medium that we’ve nurtured into adolescence to stand by it and support it in adulthood even though it might seem unrecognisable in its new form. We know the alternative: it will be out the door and hanging with the wrong crowd while we sit forlornly in the empty nest wondering what we did wrong. The first step is to stop talking about the child it once was and to put away the sentimental memories of photography as we knew it for all these years. It’s very far from dead but it’s definitely left the building.

– Stephen Mayes

Inspirations and Resources

In this fascinating video, artist Marco Breuer reflects on the unique qualities of photographic paper and the possibilities that this material can offer. Breuer highlights that while photographic paper is usually labelled ‘light-sensitive’ it also remains sensitive to other forms of manipulation.

Some questions to consider:

- How do you use photographs in your everyday life?

- Do you see any connection between everyday photography and the subject you study for A level?

- What do you think photographs will be like in 30 years time?

- What will photographs enable us to ‘see’ in the future?

- Will photographs in the future continue to be physical objects?

- Will people still be using cameras as we now know them?

- Will we still need categories like art, photography or film in the future?

Wall (1948) is eager to challenge preconceived notions and expectations, also about his own work. Days before the opening of the exhibition Jeff Wall: Tableaux Pictures Photographs 1996-2013, the artist and curator of photography Hripsimé Visser stroll through the exhibition and discuss clichés, fact and fiction around his work. This video introduces the exhibition at the Stedelijk and casts a light on Wall’s sometimes mystical and at the same time monumental photography and method which moves between reminiscence, mise en scene and realism.

TASK 1: 1000 word essay answering the following question:

What is a photograph: an index or a trace?

Read the following three texts:

Batchen G (2007). ‘Introduction’ in The Genius of Photography: How photography has changed our lives. London: Quadrille Publishing Ltd.

Sontag, S. (1977), In Plato’s Cave, On Photography. London: Penguin Books

Campany, D. (2020). ‘Introduction’ in On Photographs. London: Thames & Hudson

NB: look up my text written for students newspaper on indexicality – G Batchen, Stephen Bull, D Campany

Realism/ fiction

Follow these instructions:

- Read two texts above and select 3 quotes form each that is relevant to your essay.

- Select two images, one that represent a mirror and another that represents a window as examples to use in your essay.

- Use some of the key words that you listed above to describe what the mirrors and windows suggest.

Essay plan

Introduction (250 words): Reflect on the origin of photography and describe in your own words the difference between the two photographic processes, Daguerreotype and Calotype. Consider how they could be viewed as either a mirror or a window of the world according to John Szarkowski’s thesis. Choose one quote from Szarkowski’s text and comment if you agree or disagree.

Paragraph 1 (250 words): Choose an image that in your view is a mirror and analyse how it is a subjective expression. Choose one quote from Szarkowski’s thesis and another from Farrah Karapetian’s analysis which is opposing Szarkowski’s original point of view. Make sure you comment to advance argumentation in providing perspective.

Paragraph 2 (250 words): Choose an image that in your view is a window and analyse how it is an objective expression. Choose one quote from Szarkowski’s thesis and another from Farrah Karapetian’s analysis and follow similar procedure as above ie. two opposing points of view and commentary to provide a critical perspective.

Conclusion (250 words): Refer back to the essay question and write a conclusion where you summarise Szarkowski’s theory and Karapetian’s critique of his thesis. Describe differences and similarities between the two images above and their opposing concepts of objectivity and subjectivity.

TASK 2: Within the genre of portraiture, produce a set of 3 images that are ‘mirrors’ (subjective) and 3 images that are ‘windows’ (objective).

Add images to your essay as photographic responses to Szarkowski’s thesis and evaluate. Publish on the blog

DEADLINE: Tue 2 May

Publish essay and your photographic responses