How does the work of Francesca Woodman and Carolle Benitah explore isolation through self-portraiture?

Introduction

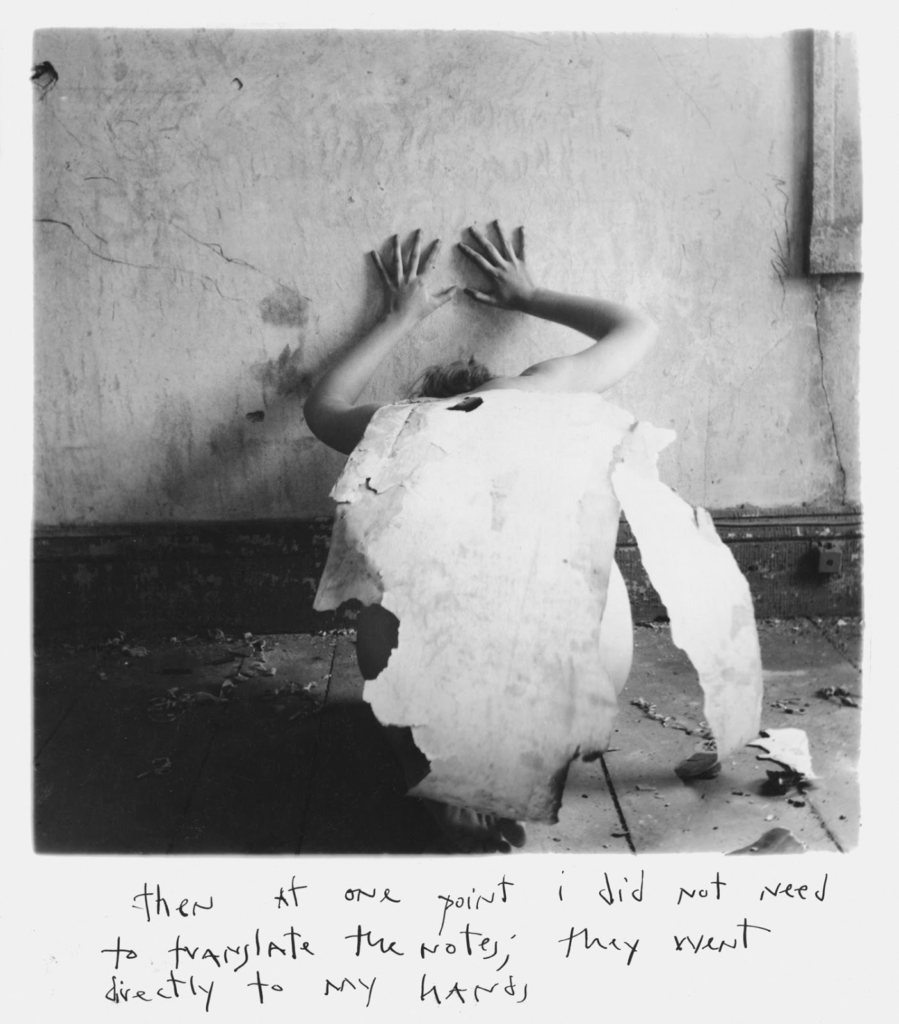

Isolation is something that we have all experienced in our lifetimes, whether from acquaintances or environments, we have all lived estranged; the work of Francesca Woodman and Carolle Benitah perfectly explores this relationship with loneliness in how they present themselves through self–portraiture. Much of Woodman’s work can be seen as surrealist and unconventional for 1970s photography. “Even when wholly present in the picture as the subject of her self-portraits, Woodman is never quite with us, never quite with herself.” She often uses this Surrealist landscape she has created to maintain a sense of escapism throughout her work. Similarly, Benitah uses Photomanipulation to change the outward appearance of herself in relation to family and heritage. When looking at these two photographers it is important to consider that they are both women photographing themselves, and how the perceptions of their work may be skewed as a result. “In the past, photographs of women were made by men for a capitalist economy to favour the male gaze and feed female competitiveness.” When viewing Woodman and Benitah’s work it is apparent it was not made with the objectification of their bodies in mind but made with the intent of reflecting on their experiences as people and women specifically the isolation that may come from that.

Significance of self-portraiture

The first known self-portrait photograph was taken in 1939 by Robert Cornielius using a camera obscura, later this was developed into a daguerreotype invented by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre that greatly increased detail captured and reduced the time needed for a subject to sit. Previously photographic portraits were only made by those with wealth and the correct equipment. As photography became more accessible as did the practice of self-portraiture. Self Portraits especially photographic are often viewed with the assumption of being an act of self-indulgence and vanity but when viewing the work of Woodman and Benitah it is apparent that this is not always the case. “The reality is that any attempt at critically examining a concept of self in a wider social context is treated as taboo, as self-indulgence. We may look in the mirror only to check our appearance, not to see through it.” Woodman’s photographs whilst they do have an aesthetic quality are less about her participation within them and instead the overall atmosphere created by the presence of her body, she is consistently unaccompanied in her photographs however she successfully obscures her face and figure through low exposures disconnecting herself as the subject creating an isolating image of pure escapism, Woodman explains her place within her images “Am I in the picture? Am I getting in or out of it? I could be a ghost, an animal or a dead body, not just this girl standing in the corner?” Whilst Woodman explains her occupancy in many of her photographs as “A matter of convenience” Putting yourself in front of a camera is mental decision and an inherent expression of vulnerability and therefore self – showing that Woodman perhaps feels isolated from her own body and experiences.

Carolle Benitah’s use of herself within her work is to observe her past and combat her history. “The photos reawakened an anguish of something both familiar and totally unknown … I decided to explore the memories of my childhood to help me understand who I am and to define my current identity.” She manipulates archive images of herself with family, however many of her family photographs contain large groups of people and it is never made apparent where and who Benitah is in each image – this works to express her theme of finding herself whilst simultaneously being unable to move away from her ‘roots’ and expected family dynamics. Benitah’s most well-known work ‘Photo Souvenirs’ is made up of three parts that correspond with three stages of life: “Enfance,” “Adolescence,” and “Adulte” compiling images of herself and family at all stages using self-portraiture as a form of documentation. The nature of the images are unsettling, family often being something we think of fondly she uses a harsh black and white when contrasted with the red of her threads to show that something is off creating a sense of dread and discomfort instead of nostalgia – The overcrowding of the pictures no longer feels homely and instead claustrophobic.

How can their work be seen a surrealist?

Surrealism as an art and cultural movement emerged in 1920s Paris around the theories of André Breton in the aftermath of World War One as a rejection of seeing the world rationally; it originally grew out of the earlier Dada movement that was characterised by its ‘anti-art’ a nihilistic approach to creating an ‘anti-aesthetic’ that defied all earlier art focusing on darker more taboo topics such as dreams, desires, and death. Surrealism focused on expressing the shifted perceptions of sanity and reality after the violence of the war. Photography came with a new challenge to the surrealist movement whilst painters could pull straight from imagination Photographers found new ways of manipulating images to achieve this aesthetic. Woodman’s work can now be called surrealist with the benefit of hindsight, in trying to appraise her work and fit it into the vast history of artistic practice it is easy to forget that woodman was a young not yet fully realised artist having committed suicide at the age of twenty-two. “We should never let go of the fact that these pictures were first created by a schoolgirl, then a student and in the end a young woman.” Woodman was still absorbing the influences around her, and we often make the mistake of viewing her work as fully complete, meaning that we ignore the raw experimentation of her photographs. Whilst her images are uniquely her own, through her use of objects inspirations such as Man Ray can be seen mimicking his use of props to create narrative. Woodman came from a family full of artists and was consistently encouraged to create, later developing an interest in mythology, you can see this fantastical element in images such as her creation of imagined landscapes places her as the main subject out of any clear time period, making her images confusing and alienating. Woodman uses commonplace domestic objects in bizarre ways to obscure herself and create uncanny haunting images.

Carolle Benitah similarly can have her work applied to the conventions of surrealism with her use of photomanipulation to distort the figures in her images and add things previously not there. “Through the trivial objects that I create and embroider, I overthrow the hierarchy of the arts.” Benitah uses the common domestic practice of embroidery to combat how family and her individual experience should be looked at. Themes throughout her work could also be called surrealist focusing on the rejection and estrangement from family an often taboo topic that is not explored in conventional art.

Representation of Women within their work

Throughout history women have been given a very specific way they should be perceived and fit into art – often something to look at instead of understand. It is recent that there has been an acknowledgement of this place women occupy within visual media. “We see photographs of women everyday, but we are used to looking at them in a few specific contexts: on products and billboards, in shop windows and magazine covers, in erotica and pornography.” Women’s bodies have now become a representation of consumerism – something to be looked at and associated with pleasure but never attached to human emotion. Most portraits of women were exclusively made by men until recently when many female photographers have become more present in mainstream media and photographs of women taken by women are now commonplace with the accessibility of modern photography. There is sentiment pushed onto many images of women created by women that it is an act of feminism, that these images are made to directly disobey the notion of the patriarchy and male dominated spaces, this in turn highlights societies issues with viewing women in art – as soon as a depiction of a women does not adhere to the preconceived ‘rules’ of how women have been depicted in media throughout history, the image is labelled as ‘feminist’ and is then often written off by the male consumerist gaze refusing to understand the image as an depiction of humanity instead of a display of ‘femininity’. “If we aren’t able to see more than an expression of feminism or femininity in a photograph of a female figure, how can we expect to see more than this when we encounter women elsewhere?”.

When looking at the work of Francesca Woodman and Carolle Benitah its important to acknowledge that they are both women using themselves as primary subject. Much of Woodman’s photographs are of herself nude however often her face is obscured by an object or blurred by low exposure and slow shutter speed creating a representation of detachment between mind and body. Woodman drew large amounts of inspiration from gothic literature and art, this influence can be seen in how she posed and used her body to imitate women within the gothic genre – Famously being filled with tropes of damsels in distress. “Feminist scholars scrutinizing nineteenth- century Gothic texts could see within their representations of femininity the effects of patriarchal structures.” Looking at works such as ‘The Nightmare’ by Henri Fuseli we can see how Woodman takes inspiration and recreates the poses of women that can be seen as vulnerable using them instead to represent herself and her mind in strange and uncanny ways. Woodman’s use of her body is outside of gender she often uses her figure to put space into perspective within her work – using her body more as a tool to take up space- young women are often taught to avoid ‘taking up space’ Woodman’s work would not exist without her physical body and is therefore in direct defiance with the notion of women being ‘seen and not heard’ which was a strong push back to the feminist movement in the 1970’s.

Carolle Beitah’s work reflects on her experiences as a young girl, a young woman, and then a fully-fledged adult. Many details within her work “echo the tense social and gender relationships of Benitah’s childhood and reflect the cultural expectations for young women in the 1960’s and ‘70s.” Benitah’s use of embroidery and commonly domestic objects reflect these expected gender roles whilst being used as defiance to these expectations from her family. “I use the falsely decorative function of embroidery to give it a different meaning than it had in family mythology.”

Benitah’s ‘Chez le photographe / at the photographer (2009)’ depicts a happy family portrait of Benitah and her siblings. She has almost completely covered her older brothers face with red dots – leaving only his mouth and chin, whilst her and her sisters are uncovered apart from their mouths sew shut with the same red thread. Benitah does this to represent the silence that is often expected of young women whilst young men can take up space and conversation without scrutiny.

Conclusion

In conclusion Both the work of Francesca Woodman and Carolle Benitah explore Isolation in different ways. Woodman uses self-portraiture to highlight that she is the sole person within the image reflecting herself and her inner state. Whilst Benitah’s crowded family photographs use subject matter and photomanipulation to invoke a feeling of solidarity. Woodman uses objects to make the viewer question the narrative behind the image and look closer to understand Woodman’s inspirations, Woodman is always with an object but never with another person within her images adding to the growing sense of loneliness throughout her work. Like woodman Carolle Benitah takes commonplace household objects and practices and use them within a new context to directly defy their preconceived connotations. Benitah’s use of domestic practices to show estrangement instead of close familial relationships that are often associated with embroidery and the passing down of such practice through generations – her use of photomanipulation is a mirror of her family life and isolation. Both Woodman’s and Benitah’s do not adhere to the male gaze and instead explore their experiences as young women often discussing topics outside of gender focusing on human experience with isolation. Woodman treats her gender as irrelevant within her work focusing purely on the existence of a body within her created spaces attempting to transcend societies notions of what she should be. Benitah instead focuses on the often toxic expectations of her as a young woman growing up in her household and the shared experience of many young girls and children isolated from their family.

Bibliography

Jansen. C Girl On Girl : Art And Photography In The Age Of The Female Gaze (2017)

Healy. C . M Girlhood (2023)

Townstead. C Francesca Woodman (2006)

Kelly. A Self Image in Wells . L The Photographic Reader

Herny Fuseli ‘The Nightmare’ (1781)

Carolle Bénitah – Tique | publication on contemporary art

Five things to know: Francesca Woodman | Tate

Surrealist photography · V&A (vam.ac.uk)

The Intricately Decorative Yet Deeply Emotional Work of Carolle Benitah | Artsy

Carolle Benitah | French Moroccan photographer (souslesetoilesgallery.net)