How does photography act as an important form of communication of both true and untrue subjects?

‘A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened. The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what’s in the picture.’ (Sontag, 1977)

Ever since the dawn of photography, its usefulness, both in cultivating the mindset of the viewer toward the subject and in communicating a message visually, has been its allure. I will be analysing the work of pioneer photo essayist W. Eugene Smith, the widely commented-on war photographer Robert Capa, and important documentary photographer of the Depression era, Dorothea Lange. This is because their work all serves a function to tell a story. Whether or not it is a true story is the key to understanding the photographer’s individualism (and, arguably, integrity) as an artist.

Historically, the truthfulness of an image is always indefinite. Photography was first used by the rich to take family portraits. These were staged and composed entirely by the photographer. The subjects’ serious demeanours and plain body language is demonstrative in itself of just how far photography has evolved since those days of long exposures and big, inconvenient equipment. The equipment used to take pictures was yet another reason for the staging of photography; it was far easier to construct a composition than to allow the world to compose itself before a long exposure. As Susan Sontag states in her 1977 publication, On Photography, ‘That age when taking photographs required a cumbersome and expensive contraption—the toy of the clever, the wealthy, and the obsessed—seems remote indeed from the era of sleek pocket cameras that invite anyone to take pictures.’ (Sontag, 1977). It is clear that the progress of industrialisation has made the camera far more accessible and hence widened the art form irrefutably. Furthermore, there was an equivalent to ‘Photoshopping’ in the days before digital imagery – photographers would manipulate the darkroom development process to create images that were more appealing to their vision. Airbrushing, dodge and burn, and blurring were all tools used by the photographer to make small (and some less small) changes to their images. Therefore, the credibility of images throughout the history of photography is uncertain. Historian of Russia David King published a photobook in 1997 called The Commissar Vanishes, which discusses the erasure of enemies of the state in official photographs throughout the Stalinist era. It is described by King as ‘a terrifying – and often tragically funny – insight into one of the darkest chapters of modern history.’ (King, 1997)

It is a perfect demonstration of how the manipulation of photographs can alter how we view history and its events; and, hence, how important it is to maintain a discourse on the truthfulness of an image. The erasure of a subject means we have no way of telling exactly who was present at the time it was taken, which only contributes to the thick cloud of uncertainty around what exactly occurred during the terror era. Furthermore, a lack of transparency on what is staged and what is candid can also cause issues in determining history’s true events. The example I will discuss in this essay is Robert Capa’s Death of a Loyalist Soldier (1936), which is one of the most famously debated images of all time. In the case of more honest photographs – such as those taken in situ – they make accessible what is inaccessible; they allow those who, in a bygone age where travel is expensive and infrequent, cannot witness alternative lifestyles and cultures to their own to access this in a new medium. This is why the work of W. Eugene Smith was so important at the time; it was both educational and exciting for those who were unable to see it for themselves. Therefore, the importance of photography in relaying the events of history should not be understated – it is imperative that we as artists continue to use the medium to its advantages; to both document and inform.

The photo essays created by W. Eugene Smith between 1945 and his death in 1978 explore a variety of subjects, ranging from Minamata (1974), which explored the horrors of the mercury poisoning disaster in Minamata, Japan, to Nurse Midwife (1951), which told the story of an African American South Carolina nurse and midwife named Maude Callen.

Smith’s work is constantly empathetic and he always worked tirelessly in his pursuit of the story – when photographing the invasion of Okinawa in 1945, he was critically wounded, and when he was photographing for his final essay in Japan, he was violently beaten by workers at the chemical factory who didn’t want his photographs to expose the suffering of the poison victims. This is illustrative of Smith’s devotion to his craft. This insatiable need to capture is a trait seen in many photographers, and it truly characterises his work. The structure of his photo essays has been replicated many times since they were published, by other artists who saw how successful the structure was in relaying the tale that Smith wanted to tell. This is perhaps why he has repeatedly been described as ‘perhaps one of the greatest photojournalists America has ever produced.’ (McGuire, 1999), and it is said that ‘the combination of innovation, integrity, and technical mastery in his photography made his work the standard by which photojournalism was measured for many years.’ (The International Center of Photography (ICP), n.d.) However, because of his insatiable and unending desire to photograph, there was an enduring issue with copyright across Smith’s work, namely his essay from Minamata, Japan. The photograph titled Tomoko and Mother in the Bath caused issues because the parents of Tomoko felt that her image was portrayed in an exploitative and dehumanising manner.

The image was their final and enduring memory of their daughter, and the stigmatizing nature of the portrayal calls Smith’s ethics into question. Furthermore, the family had no rights to the image and so, whilst it was making money that went straight to Smith, Tomoko’s family was struggling to feed and care for their daughter. The unauthorised uses of this image led Tomoko’s father to tell the media that “many of the organizations working on our behalf are still using the photograph in various media, many of them without our consent…I realize this is necessary for numerous reasons, but I wanted Tomoko to be laid to rest…” (Uemura, 1999). The long and arduous case was naturally taxing on Tomoko’s parents, and it was only in 1998 (24 years after the photograph had been published) that Smith’s wife, Aileen, travelled to the family to give them the rights to the image. This was helpful for the Uemuras, but it did not undo the years of harassment and hate they had received for the existence and fame of the image. Thus, it is important to question the ethics of Smith when reviewing his revolutionary and historically acclaimed images. Even though Smith acquired this image unethically, it is certainly a representation of how he pursues the creation of a story over all else. Therefore, his essays still present an important example of how photography is, first and foremost, a medium through which to craft a narrative, making them an important piece of evidence in this investigation.

Robert Capa is widely renowned for his work photographing the Spanish Civil War in 1936, and chiefly for his most famous image, Death of a Loyalist Soldier (1936).

This image was supposedly taken above a trench after Capa ‘just kind of put [his] camera above [his] head and even [sic] didn’t look and clicked the picture, when they moved over the trench’ (Capa, 1947). In 1975, British journalist Philip Knightley was the first to make the allegation that the image was staged when other staged images were discovered to have been taken in the same place at the same time. In 2009, José Manuel Susperregui of the University of País Vasco published Sombras de la Fotografía (“Shadows of Photography”), which asserted, by analysing the mountain ranges in the background of the sequence, that the image was taken in Espejo, some 50 kilometres from the alleged location at Cerro Muriano. It has since transpired, in Richard Whelan’s 2007 publication This is War: Robert Capa at Work, that, on the evidence of both forensic expert Captain Robert L. Franks, the chief homicide detective of the Memphis Police Department, and Hansel Mieth, a Life staff photographer in the late 1930s. Franks asserts that, based on the subject’s closed hand and limp body, his reflex response was not engaged as it would be if the image was staged, that he had instead just been shot. This was then supported by a letter from Mieth to Whelan in 1982. She asserted that Capa had told her, very upset, that the image was taken when they were ‘fooling around’, and suddenly, ‘it was the real thing. I didn’t hear the firing—not at first.’ (Whelan, 2007). It is clear now that the image was taken when the man was shot, however, it was still not taken in battle as was claimed by Capa. He felt personally responsible for the man’s death. This is perhaps why he did not discuss the image widely and concealed its true circumstances. Hence, the image is of what was asserted by Capa; a man being shot during the Spanish Civil War, but it was not taken at the time nor place he gave, indicating that he intentionally deceived his viewers. Whether or not this reflects positively or negatively on Capa as a photographer is up to the viewer; is it wrong to deceive the world if the pictures still serve the intended purpose, or is it dishonest to incorrectly document history?

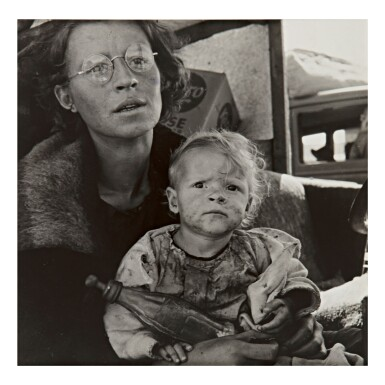

Another artist whose work could be construed as dishonest is Dorothea Lange, most famous for her documentary photography during the Depression era in America. Travelling through California whilst working for a government agency responsible for providing aid to struggling farmers, Lange took her most famed image, Migrant Mother, in 1936. This image is renowned for its captivating, evocative tone, and it is still viewed worldwide as an important insight into civilian life in Depression era America. However, I am more concerned with two images taken by Lange three years later, in 1939. The first, shown below, was taken after the photographer introduced herself and asked to take their picture. The subjects smile and the father wipes the baby’s face.

The photo that became more famous, after it was used by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) to demonstrate the effects of the Depression, was this one.

It is clearly the un-staged version in which the photographer has captured the subjects’ natural states. The general caption for this series of images reads ‘The car is parked outside the Employment Office. The family have arrived, before opening of the potato season. They have been on the road for one month–have sick baby…Father washed the baby’s face with edge of blanket dampened from canteen, for the photographs’ (Mason, 2010). This shows that Lange does not intentionally represent the effects of the Depression in this way; it is instead the FSA that widely publicise this particular version of the photograph. This is because the organisation has an agenda to bring awareness to the issues caused by the government mismanagement and hyperinflation of the time, especially in rural California, where the issue of the Dustbowl caused an extreme lack of fertile ground and, hence, a widespread hunger. Sontag, in her 1977 publication, On Photography, discussed the photographers of the FSA and asserted that ‘in deciding how a picture should look, in preferring one exposure to another, photographers are always imposing standards on their subjects.’ (Sontag, 1977) The representation of civilian life therefore has a palpable effect on how we view the period; we are not able to imagine what life could have been like unless we personally experienced it, and, therefore, photographs are the tool we use to unlock the intricate details of (fairly modern) history. This therefore demonstrates once again how important it is to understand and also challenge the source of an image – who took it and why? What could their intentions have been? Were they commissioned to take it? If we neglect to, we could fall into the trap of passing history down incorrectly.

Overall, it is clear that the importance of photography lies very firmly in its power as a window into the past, and into the presently inaccessible. One reason that humans are inherently captivated by the medium is the way in which it allows us to freeze time forever in a single exposure that appears exactly how it appeared to us in the moment. There are of course, as I have explored in this essay, many ways in which a photographer can manipulate the scene, so it is different to how it appeared in the moment, and this is a further reason as to why we feel such attraction to photography; it allows us to become puppeteers, narrators, and storytellers. I think that this holds importance as it reveals that the human race is programmed to tell stories, whether these be true or untrue, and that they enjoy the consumption of such stories. The existence of photographic archives all over the globe demonstrates further that history is only as rich as we make it; we are the creators of ‘history’, and so we are responsible for the maintenance of its truths. The ethical dilemma of recording an event to which the photographer is more than just a passive observer is important in this debate also. As Sontag states, ‘it is a way of at least tacitly, often explicitly, encouraging whatever is going on to keep on happening’. This suggests that photographers are wrong to continue documenting a situation which can be prevented, yet also there is an ever-present counterargument which states that it is wrong to intervene in the events they photograph. Smith’s methods are representative of this dilemma, which, to me, makes his work even more interesting in this discussion of morality.

Bibliography

Capa, R., 1947. Bob Capa Tells of Photographic Experiences Abroad [Interview] (20 October 1947).

King, D., 1997. The Commissar Vanishes. 1st ed. London: Tate Publishing.

Mason, J. E., 2010. How Photography Lies, Even When It’s Telling the Truth: FSA Photography & the Great Depression. [Online]

Available at: https://johnedwinmason.typepad.com/john_edwin_mason_photogra/2010/03/how_photography_lies.html

[Accessed 22 January 2024].

McGuire, R., 1999. Unforgettable book combines art, artifact ‘W. Eugene Smith, Photographs, 1934-1975’. [Online]

Available at: http://edition.cnn.com/books/reviews/9901/04/eugene.smith/

[Accessed 19 January 2024].

Sontag, S., 1977. On Photography. 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

The International Center of Photography (ICP), n.d. Artist: W. Eugene Smith. [Online]

Available at: https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/constituents/w-eugene-smith?all/all/all/all/0

[Accessed 19 January 2024].

Uemura, Y., 1999. Letter published in newsletter that circulated among Minamata patients. Minamata: s.n.

Whelan, R., 2007. In: This Is War! Robert Capa At Work. New York City: ICP, pp. 72-73.