In what ways do alterations in Jessa Fairbrother’s work make the visible what is invisible?

‘This is my story of severance’- an opening quote by Jessa Fairbrother for her book “Conversations with My Mother.”

The essence of photography lies in its ability to capture precise details and faithfully represent the reality perceived by humans, setting it apart from traditional methods such as drawing and painting. Yet, it is crucial to acknowledge the profound impact of art within the realm of photography. Throughout history, various forms of art, including poetry, acting, music, and photography, have consistently moved people. This exploration seeks to delve into the reasons behind the compelling nature of art, its capacity to inspire extraordinary outcomes, and the inherent meaning and thought embedded in creative expressions.

While photographs are often considered as objective records of reality, this investigation recognizes the transformative power of art. It sheds light on seemingly ordinary works that possess a subtle element capable of elevating them to a level of profound significance. The focus here is on understanding how alterations to images can significantly influence the overall message conveyed by a photograph.

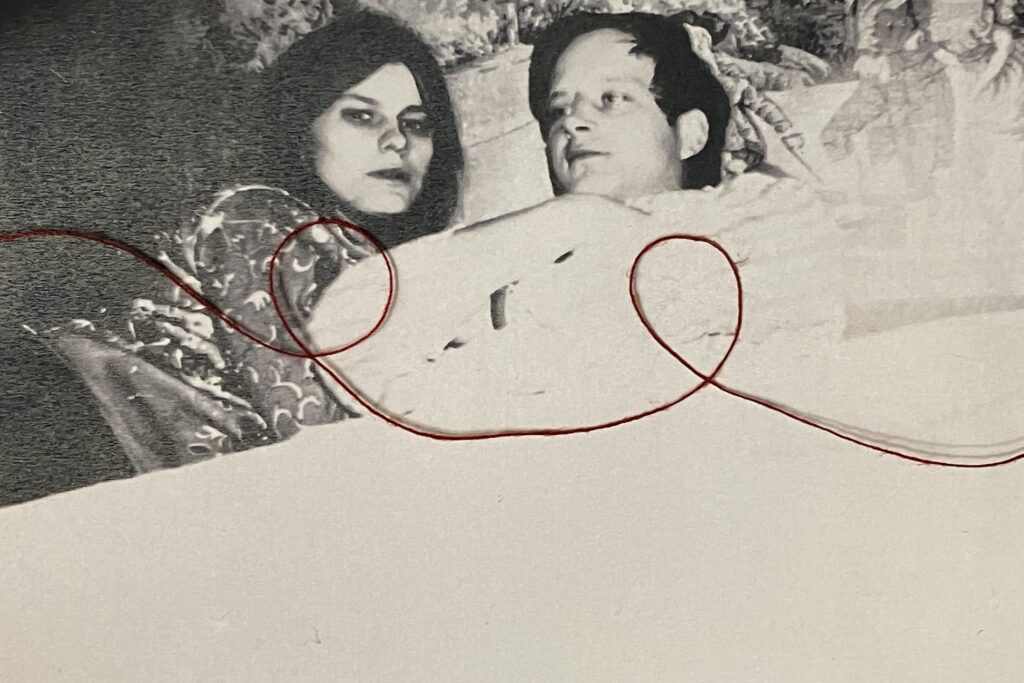

The exploration further aims to evaluate the success of Jessa Fairbrother’s photographic outcomes, particularly in her project “Conversations with My Mother.” By employing unconventional methods such as thread, ink, burning, and other “destructive” techniques, Fairbrother manages to enhance the depth and meaning of her photographs. This study delves into the experimental nature of her work, questioning why and how these unconventional methods contribute to the success of her artistic expressions. “Conversations with My Mother” becomes a focal point, aligning with the genre of the researcher’s personal study. The project encompasses qualities that resonate with the exploration, such as the profound exploration of her mother’s life intertwined with her own, the visual representation of the connection between them, and the physical engagement with the art through alterations, mirroring the essence of the broader investigation.

Pictorialism, Surrealism and Symbolism

Early examples of pictorialism:

Image 1. Edward Steichen. The Flatiron (1905); printed (1981) from the Early years portfolio, 1900-27

Image 2- Petrocelli, Joseph: The Curb Market – New York

Image 3-The gargoyle

(c. 1900)Gertrude KASEBIER

Pictorialism emerged as a significant photography movement in the late 19th century, peaking in the early 20th century. The technical process of photography, involving film development and darkroom printing, originated in the early 19th century, gaining popularity for traditional photographic prints around 1838-1840. As photography evolved, debates arose among photographers, painters, and others about the scientific and artistic aspects of the medium. English painter William John Newton suggested in 1853 that artistic results could be achieved by keeping images slightly out of focus, while others saw photography as a visual record of a chemistry experiment. Photography historian Naomi Rosenblum noted the dual character of the medium, capable of producing both art and documentation.

Amidst these debates, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of Pictorialism, a movement characterized by its aim to elevate photography to fine art. Pictorialists manipulated photographs through techniques like soft focus, light and shadow manipulation, and alternative printing processes to create images resembling paintings or etchings. This movement blurred the boundaries between photography and traditional art forms, fostering a more inclusive approach to visual art. While Pictorialism waned in popularity, its emphasis on subjective interpretation and creative expression paved the way for subsequent photographic movements, including Modernism. Pictorialist photographs often lacked sharp focus, featuring visible brush strokes or surface manipulations to project emotional intent.

“I could play with light and shadow, creating a new reality with the same elements of the visible world.” said Ray, in this quote he unfolds the process of his techniques as well as encourages us to think more creatively when it comes to ordinary objects, as even the simplest of elements can be turned into something extraordinary through the use of light, in a darkroom.

Surrealism, on the other hand, emerged as an artistic movement characterized by an interest in the irrational, dreamlike, and subconscious. Led by André Breton, Surrealism aimed to reconcile the contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality or surrealist. This movement significantly impacted various artistic disciplines, including photography. Key figures in Surrealist photography, such as Man Ray, Claude Cahun, and Salvador Dalí, contributed to the exploration and expression of the mind beyond conscious reality. Man Ray, associated with Surrealism, experimented with solarization and photograms, creating dreamlike and abstract images. Surrealism encompassed literature, visual arts, film, and photography, spreading globally from the 1920s onwards. They embraced techniques such as multiple exposures, photomontage, and distortion to create visually and psychologically charged images. Surrealism’s impact on photography helped widen the possibilities of the medium, encouraging photographers to explore the subjective, and the imaginative. The movement’s legacy is still seen in the ongoing exploration of unconventional and dream-inspired visual narratives in contemporary photography.

BRETON, ANDRÉ

In Surrealist Manifesto, Breton defined surrealism as: “pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought.”

However, the Surrealist movement was not officially proven until after October 1924, when the Surrealist Manifesto released by French poet and critic André Breton, became successful in claiming the term for his group over a rival group led by Yvan Goll, who had published his own surrealist manifesto two weeks prior. The most important centre of the movement was in Paris, France. From the 1920s onward, the movement spread around the globe, affecting the visual arts, literature, film, and music of many countries and languages.

Symbolism in photography entails utilizing visual elements to convey metaphorical or symbolic meanings that extend beyond the explicit representation. Photographers employ symbols to elicit emotions, communicate ideas, or narrate stories that transcend the superficial aspects of the image. This approach fosters a deeper and more subjective interpretation of the photograph by the viewer. A great example, one of the most iconic symbolic photographs is the Migrant Mother, photographed by Dorthea Lange.

Naomi Rosenblum comments ” The images were transformed into photographic works of art when they were exhibited under auspices of the Museum of Modern Art”.

The origins of photographic symbolism can be traced back to the broader Symbolist movement that emerged in the late 19th century. Symbolism, as an encompassing artistic and literary movement, sought to communicate abstract and emotional ideas through symbolic imagery. Within the realm of photography, Symbolism evolved into a potent tool for photographers to move beyond mere representation and delve into more profound and subjective themes. Early photographers, including Julia Margaret Cameron, incorporated symbolic elements in their work, drawing inspiration from literary and mythological themes. During the same period, photographers active in the Pictorialism movement also embraced Symbolism as a means of elevating photography to the status of an art form. Despite fluctuations in popularity, Symbolism continued to manifest in the works of individual photographers and experienced a resurgence in the latter half of the 20th century and beyond.

Jessa Fairbrother, an accomplished British artist, focuses her practice on emotions and the human body, utilizing photography, performance, and stitch as mediums. Trained initially as an actor in the 1990s, she later completed an MA in Photographic Studies at the University of Westminster in 2010, enriching her understanding of the intersection between artwork and audience. Fairbrother often incorporates elements of self-portraiture in her work, delving into themes related to identity, femininity, and the body.

One of her particularly intriguing projects is “Conversations with my mother.” In discussing this project, Fairbrother revealed that it not only explores her relationship with her mother but also addresses her inability to conceive, thereby altering the anticipated maternal role she had hoped to shape — rendering her “Neither daughter nor mother.” The project commenced with a joint photographic endeavour with her mother, involving the exchange of a disposable camera through the mail, documenting their lives from their respective viewpoints. However, Jessa’s discovery of her infertility, followed by her mother’s diagnosis of cancer, dramatically shifted the narrative. Becoming her mother’s caregiver, Fairbrother left her existing life to be with her during her final moments. The resulting photographs include portraits of her mother, as well as self-portraits adorned with her mother’s wig after her passing. Some images within the project are deliberately destroyed, symbolizing the internal destruction she experienced.

This destruction is not only seen through the photographs themselves but through her own words: “I cried in sorrow at the abrupt suspension of future narratives: for the mother I would not hold again and for the child who would never hold me.”. This loss effected her and this book is a representation of that.

Shifting back to ideas of Pictorialism, and Symbolism as well as Surrealism, these are the main genres her body of work revolves around, each photograph has aspects related to the subject, like the subject of infertility or subject of her losing her mother. These sometimes little sometimes big elements of Symbolism give the photograph more depth and emotional connection between the viewer and the photograph. Regarding the technical aspects behind her photographs, they are quite pictorial, they are positions, or stages in a way to create a visually pleasing photograph, which is then tampered with. The experimentation and physical alterations to the images especially labels her work as all the above, it is visually pleasing, it is taken for artistic purposes, it has symbolism through the alterations, and it is surreal through the literal yet sometimes harder to find metaphors. “I burned, buried and embellished photographs of us. I performed my grief and began to stitch.”, the metaphors behind the alterations are explained though that quote, that each photograph carries grief that is imbedded through the processes.

Fairbrother employed various techniques in this project, with each contributing to the visual and emotional impact of the images. For instance, using tissue and carefully burning each layer adds an intriguing dimension to the photographs, enhancing their visual appeal and conveying deeper meaning. Another captivating series involves stitched portraits of her mother and herself, each featuring a similar swirly pattern but with distinct colour variations. The stitching raises questions about the symbolic significance of colour, pattern placement, and the overall representation of the images. The layout of the project within the book is diverse, but it takes a distinctive turn with the montaged page. This spread across two pages features a collage of 14 images, predominantly focusing on nature — her mother’s garden. However, interspersed are images that appear older, potentially from her or her mother’s childhood, culminating in the central image of a pregnancy test. The combination of these pictures weaves a narrative, with each element holding importance. The pregnancy test, for instance, may symbolize her infertility, while the other images capture moments from both her life and her mother’s. Jessa Fairbrother’s project “Conversations with my mother” stands as a poignant exploration of personal struggles, mother-daughter relationships, and the intricate layers of human experience, showcased through the lens of photography and artistic expression.

When I discuss her work, I can’t help but envision a photograph that my mind comes back to, these ones being the two portraits, one being of her mother and the other of Jessica herself. When displayed next to each other they hold more meaning than separate, this is due to the link between them as well as the photographs. What differentiates them from any other portraits, is Jessica’s signature style of embroidering into them. She contrasts the portrait with stitched abstract shapes, changing the colours of the thread according to each portrait. These raise questions for the viewer, but especially, why? Why this patter, thread, colour? To me I like to think that the colour choice is not so random but symbolises something greater. I think it shows how she felt about her mother a lot, by stitching more colours together but for her only sticking to grey. To me it represents her as a person, showing her mother in a spotlight, showing she meant to her more than herself, or displaying her mother through connotations of how her soul felt, vibrant, kind, lively. This stitching itself uncovers the meaning embraided with it, although we can’t see her mother like she does, we can see her through her eyes, and that’s why it holds such poignant significance. It is the symbolism behind the images is what I want to imbed into my own work I want to be able to display the emotions behind each photograph through manual and digital alterations.

Overall, any photograph is produced due to an emotional experience, change or affect a subject has on the photographer. Photographs are a work of art, which needs to be celebrated, however the most successful ones are the ones that question us, and to me that is one of the most important qualities, because to question is to be intrigued, to be curious and confused. But, also to want to know the truth hidden behind a photograph, in another words “To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed.” – said Susan Sontag in the book On Photography. It means to have a relation with the subject, for the subject to have an impact on a photographer. Photographs revoke feelings in us, so any successful photograph should do so. Without feelings created the photograph will not hold less significance to the viewer. Now it is important how the photographer displays these feelings through their work, in Jessica’s Fairbrother’s case, it’s through her manipulations and alterations, specific stitching, burning, collaging and physical changes she can do on a printed photograph she displays emotions. In another words she makes the visible what is invisible.

Bibliography

https://www.britannica.com/technology/Pictorialism

https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/surrealism-photography

https://www.lensculture.com/articles/jessa-fairbrother-conversations-with-my-mother

https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/33/severance-jessa-fairbrother-conversations-my-mother