‘Our mission is to produce and facilitate research on the Island’s history, culture, language and environment; and to share that knowledge with the widest possible audience for the benefit of our island community.’ Founded in 1873, by only a small group of Islanders, the Société Jersiaise holds around 35,000 historical images. Although it started with a small number of people interested in the study of history, language and antiques of Jersey, it soon grew a larger membership, and the historical documents were published. Their main record of their activities in the Bulletin Annual in 1875. In 1893 the museum became permanent and moved to 9 Pier Road. Now looked after and owned by Jersey Heritage, the collection is still growing. Their main mission is to make the Islands history available for people to see and admire, researching its history. They achieve their mission to research the Island’s history through their active sections, research collections, community outreach and collaborations with the local heritage partners. They have been making long term studies possible since 1873 with their volunteer sections that produce the raw data. They specialise from archaeology to zoology. What can we learn from Jersey looking at pictures of the past? Holding a substantial amount of bibliographic, cartographic, photographic and research collections, the Société uses these as a sort of ‘long-term memory’ to supply an important resource showing the value of community through the heritage and archives. The archives are also a way to show the Island’s identity and environment and how it has developed through the years, holding a rich knowledge of the history and past Islanders. The Jersey archives create the personal question of what archives do we, as current Islanders and people, keep to preserve our history. Contemporary archives can vary from text messages, to digital images, to social media posts. They all hold a sense of history and knowledge about ourselves, however they do not have the same value as physical archives created with a purpose to inform the future generations about the past. The transformation in the change of photography is colossal. Comparing present day to even 50 years ago, a large difference can be seen. Images used to be taken with no knowledge of the outcome, developed, and then stored in boxes or picture frames to be admired personally. Now anyone can take an image, edit it, and post it publicly. I find this leaves less room for admiration of so-called archives these days, and the new generations are losing the knowledge and care that comes with looking after images. This could cause problems in the future for the Société Jersiaise.

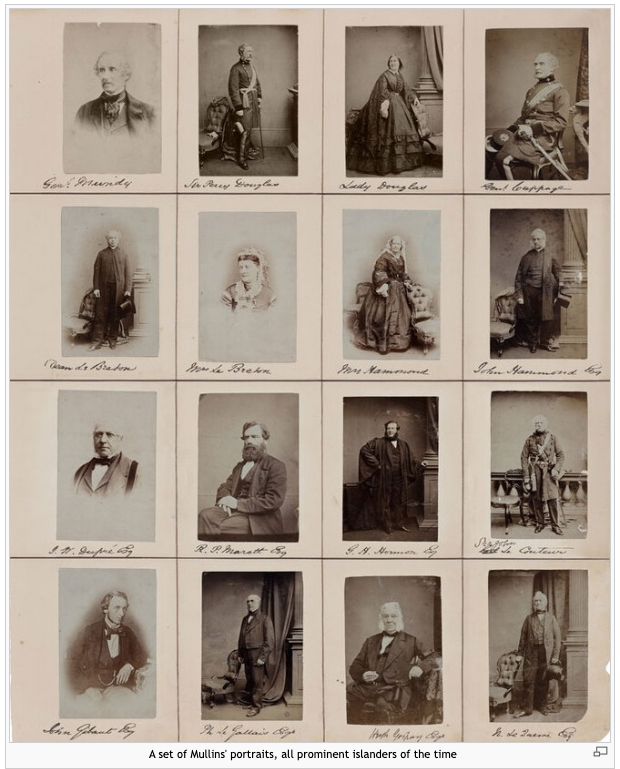

Henry Mullins was an important figure in the first generation of Jersey photographers during the nineteenth century due to the fact that he managed to create thousands of portraits of Islanders from 1848 to 1873. He had a studio in the Royal Square that was very successful. His success was assisted by the circle of photographic pioneers at the Royal Polytechnic Institute, Regent Street, London. In 1841, the first photographic studio in Europe arrived there. His profession was first recorded in Edinburgh, 1843, before moving to Guernsey then deciding to live in Jersey a year later in 1848. His work presents mainly the upper class because of the price it was to take an image. His most well-known work is Cartes De Visite containing 9600 images, typically in sets of 16. It cost around 10d 6d to have these images taken. These images are now stored in the Société Jersiaise. Mullins was known for being favoured by officers of the Royal Militia Island of Jersey. It was typical for these officers to have their portraits taken, including their families such as wives and children. These images present the fashion in the mid- 1800s for long hair, moustaches and large beards. Some may say that it is difficult to depict a difference between some of the men due to the styling of these images. Mullin’s images offer us knowledge about the classes and how photography was used in the 1800s. Being archives stored in the Société Jersiaise, it allows us to analyse and discover Jersey’s past, and even compare it to present day. Archives such as these are more than an interesting portrait to look at, but are a part of Jersey’s history, giving Islanders knowledge into their heritage. After Henry Mullin’s passed away, over 20,000 negatives were given to the Société Jersiaise, allowing his collection of archives to be even richer.

Mullin’s used the calotype method for his image making, as it said in an advert in the Jersey Times, ‘Instruction given in the Calotype, Energiatype, or photographic processes, and proficiency guaranteed for a fee of five guineas”.’

The calotype was invented by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1841. Although it was surpassed in the 1850s by the collodion glass negative, for its time it was an adequate invention. The process used a paper negative, creating a print with a softer, less sharp image than the daguerreotype. However, because a negative is produced, it was possible to make many copies afterward. The fabric of the paper was contained in the image, rather than on the surface, meaning the paper fibers tended to show through on the prints. This can be seen in the example image above, created by Henry Mullins. This was typical in his work because the calotype’s image results were a lower quality print. Mullins’ collection of images like this provides a good amount of information about the people of Jersey in the 1800s, and their families. Although the images are mostly basic head and shoulder images, you can see the relation between individuals in the collection. There is a pattern of split shadow lighting on the portraits, showing that lighting was used to aid photography at the time, whilst informing us about Mullins style of image taking.

Overall, learning about the importance of archives has broadened my perception about images from the past. It is shown to clearly be important for informing this generation, and future ones to come, about the social structures of Jersey’s different groups. This can be presented through the fact that photography was for the wealthy in the 1800s, proven through Henry Mullin’s collection of images of Jersey’s hierarchy, like officers. The fact that mostly only the affluent officers could afford for their wives and children to have portraits emphasises this. Exploring archives has inspired me to look at a variety of photographers that are not just contemporary and alive today. It has given me the ideas to look at more archived images, and present nostalgia through a more historic view, such as Ansel Adams or Alfred Stieglitz, and experiment with their lighting and shooting styles.