Camera Obscura & Pinhole photography

Camera obscura Has been used for many years. Suggested by anthropologists, the idea occurred in the Palaeolithic era and was used by hominins. It is thought that they used “keyholes” carved into caves to project images and create cave paintings. The technique of tracing from a camera obscura is shown through these paintings from the time. It was also used to study eclipses without the risk of damaging the eyes by looking directly into the sun. The camera obscura is known as the earliest form of art technology, professionally known as archaeo-optics. Around 300 BCE, the Greek mathematician Euclid proposed a theory called “geometry of vision” which is thought to clarify the technology and mechanics behind light perception. His writings were not directly linked to the camera obscura, but his writings did explain how and why vision works.

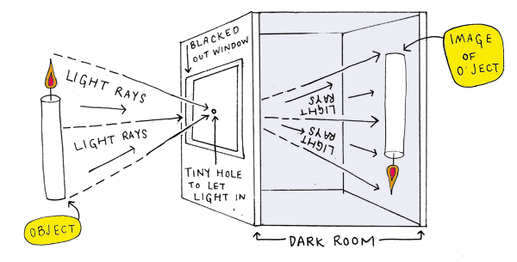

The diagram below shows how light projects at different angles, similarly to al-Haytham’s.

The basic idea of a camera obscura is to project a reversed image onto the wall by blacking out a room from light and creating a small hole lens in the wall. The name ‘Camera Obscura’ translates from Latin as ‘dark chamber/room’. The camera obscura uses two ways of manipulating light: refraction and projection. A glass lens can also be used to refract and manipulate the light to project the image onto a surface, as well as projecting the outside world using a pinole and letting the light in. In both cases the image will be projected upside down because light travels in a straight line.

Nicéphore Niépce & Heliography

Nicéphore Niépce is supposedly the first person to create a permanent photographic image. He was a French inventor, born 1765 and died in 1833. Later inventing an international combustion engine in 1807 with his brother, and beginning to experiment with lithography. After being unsuccessful in obtaining proper lithographic stone locally, he found a way to provide images automatically. Niépce coated pewter with a variety of light-sensitive substances in an attempt to duplicate superimposed engravings in sunlight. In April 1916, he progressed this idea into photography, which at the time he named heliography (sun drawing) with a camera. He created his first successful photograph on paper sensitised by silver chloride, capturing a partially fixed image of a view from his workroom. In his next attempt he used multiple supports for the light-sensitive material. He used a type of asphalt, Bitumen of Judea, which hardens in exposure to light. Finally, in 1826/ 1827 he used a camera to create the first permanently fixed image. Not only did Niépce resolve the issue of reproducing nature by light, but he invented the very first photomechanical reproduction process. In 1829, he finally conceded to Daguerre’s repeated overtures to perfect heliography because the exposure time was drastically shorter.

Louis Daguerre & Daguerreotype

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre invented the daguerreotype process in France. The daguerreotype is a direct-positive process (no negative is made) that creates detailed images on a sheet of copper plated with a thin coat of silver without the use of a negative. The process needed a lot of care due to the detailed and thorough preparation. The silver-plated copper plate needed cleaning and polishing to make the surface look like a mirror. The next step was to sensitize the plate in a closed box of iodine till it resembled a yellow-rose appearance. Then, whilst held in a light proof holder, the plate was transferred to the camera. It was then exposed to light, and the plate would be developed over hot mercury to create an image. Fixing the image meant immersing it in a solution of sodium thiosulfate or salt and toning it with gold chloride. Unlike Niépce’s exposure times of around 8 hours, the Daguerre’s exposure varied from three to fifteen minutes. Daguerreotypes could be copied and produced by lithography or engraving but don’t produce a negative.

The cameras used for daguerreotypes were made by either the photographer themselves, opticians or instrument makers. A sliding-box design was the most popular, where the lens was placed in the front box and a second smaller box would slide into the back of the bigger box. You could control the focus by sliding the rear box front and back as a reversed image was projected. This reversed image could be corrected by inserting a mirror or prism into the camera. After the sensitized plate had been put in the camera, you would remove the lens cap to begin the exposure.

Daguerreotype Plate Sizes:

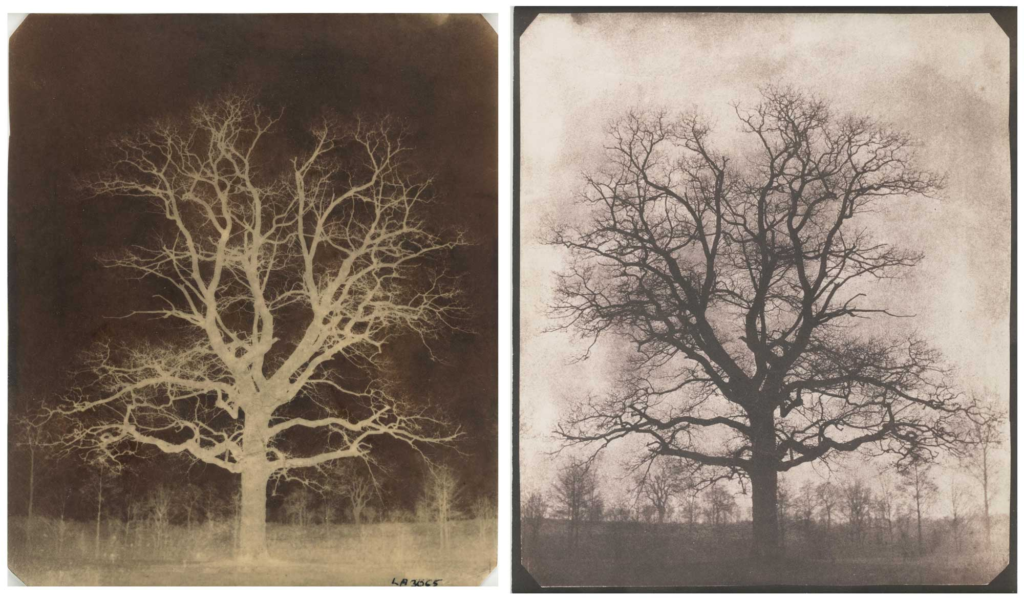

Henry Fox Talbot & Calotype

William Henry Fox Talbot, an English chemist, linguist, archaeologist, and pioneer photographer, was born in 1800 and died in 1877. He is well known for his development of the calotype, This was an early photographic process – an advancement of the daguerreotype. The calotype can also be called a talbotype. This process involved coating a sheet of paper with silver chloride and exposing it to light in a camera obscura. The parts that were hit by light turned dark in tone, producing what Talbot called a “negative” image. This was new and different to the daguerreotype, which could only produce positives. Talbot’s revolutionary part of the process was due to his discovery of the chemical gallic acid that was perfect for developing the image on paper. This acid speeds up the reaction of silver chloride and the exposed light. The exposure times overtook Daguerre’s technique, and shortened it to around one minute. He would then fix the photo on the paper with sodium hyposulfite. Being able to create an unlimited number of negatives (by simple contact printing upon another piece of sensitized paper) meant this technique was the quickest and best technique for taking photos.

Robert Cornelius & self-portraiture

‘The first selfie‘ – Cornelius was 30 years old when he used the daguerreotype process, just after it was introduced, to capture the world’s first self portrait image in 1839. He stood solitary in his family’s yard in Philadelphia, late October, with his own makeshift camera. Its lens was fashioned from an opera glass. Making sure the daylight was perfect to expose his pre-prepared metal plate in the camera, he took the image. The exposure time was around 10-15 minutes, causing him to stand still for the whole exposure. Rachel Wetzel of the Library’s Conservation Division stated “Taking a portrait is astounding in 1839,”. This was the start of something new at the time, influencing the future generations and its photography. This Library obtained his self portrait in 1996. Over time they collected a variety of Cornelius’ work, including his great-great-grand-daughter’s donation of an important collection of his photographic materials and ephemera.

“The collection gives a much broader picture of Robert Cornelius at the Library, beyond the photographs we currently hold,” – Micah Messenheimer of the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division.

Julia Margaret Cameron & Pictorialism

Margaret’s work began at the age of 48, as a mother of six children, when she received a camera as a gift from her daughter. This caused her to pursue her dream of photography and make it a lifestyle. Before receiving her first camera, Cameron had compiled albums and had experimented with printing images from negatives. At the start of the photography journey the process involved a lot of physical work using possible hazardous materials. She used a wooden camera that was large and inconvenient and placed it on a tripod. Using the common process of producing albumen prints from wet collodion glass negatives, she needed a glass plate (around 12 x 10 inch) to be coated with photosensitive chemicals in a darkroom and exposed in the camera when still damp. She would then return the glass plate to the darkroom to be developed, washed and varnished. Through this process she could duplicate prints by placing the negative directly into sensitised photographic paper and exposing it to sunlight.

After experimenting with her new camera, she created her “first success” which was a portrait of a little girl, Annie Philpot. Her early portraits show how she experimented with a soft focus and dramatic lighting. These features later became her signature style. A soft focus lens deliberately introduces spherical aberration in order to give the appearance of blurring the image while retaining sharp edges. It is created from lens flaws, where the lens forms images that are blurred due to spherical aberration.

“I was in a transport of delight. I ran all over the house to search for gifts for the child. I felt as if she entirely had made the picture.”

Cameron took a unique approach to her photographs as she included her imperfect images, such as ones with fingerprints, streaks and swirls in. This differed from other photographers that would reject images with technical flaws. She even manipulated her negatives by scratching into them. This photo of Julia Jackson shows her manipulation in the background where she scratched a picture into the background.

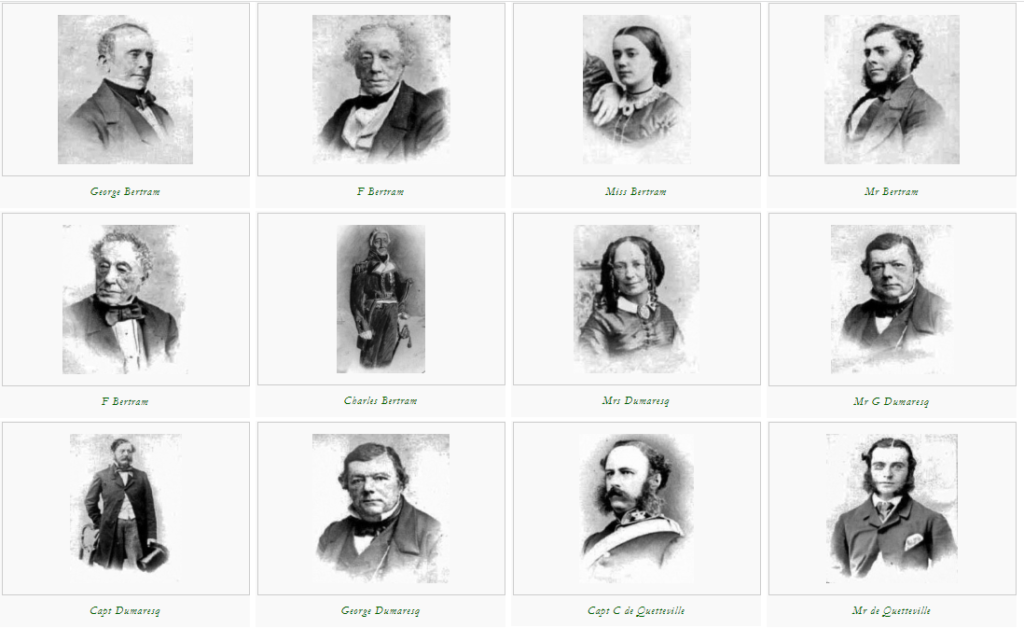

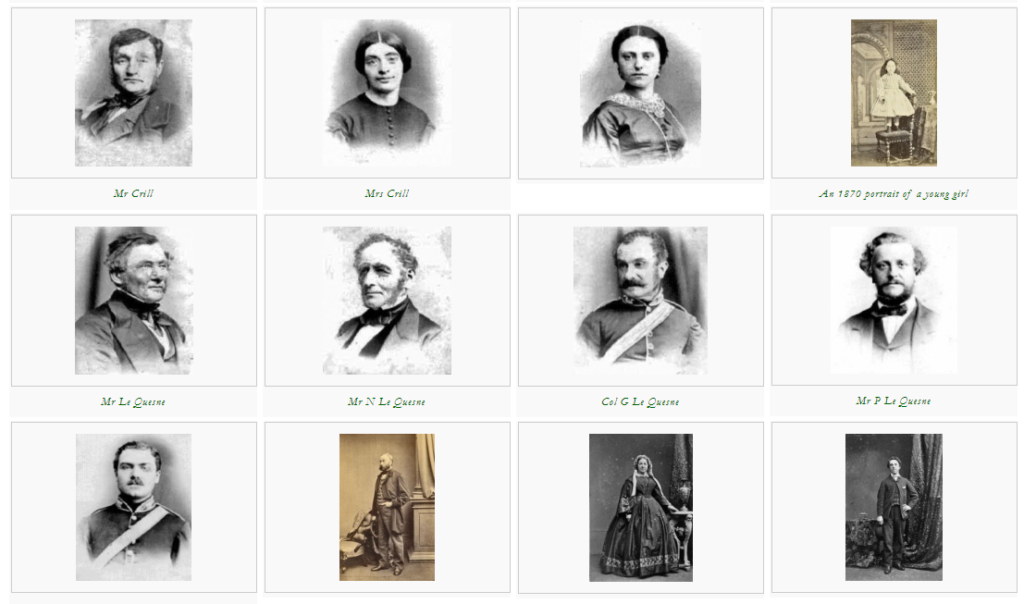

Henry Mullins & Carte-de-Visit

Moving to Jersey in 1848, Henry Mullins set up a studio known as the Royal Saloon at 7 Royal Square after previously working in London. He is well known for his cartes de visite and the photographic archive of La Société contains a large collection of these. Containing 9600 images, the online archive holds photos mainly in sets of 16 photographs taken at a single sitting. As photographs were expensive at the time, Henry mainly photographed Jersey’s affluent and influential people. These include Dean Le Breton (he was ordained Deacon in 1839 and priest in 1840).

Mullins was in demand with officers of the Royal Militia Island of Jersey. It was very popular for them to have their portraits taken, including their families of the more important officers. Long hair, whiskers and beards were shown to be in fashion in the mid-1800s from Mullins’ photos. Due to this and the styling for the portraits, it is difficult to tell the difference between some of the officers in the portraits.

BIBLIOGRAPHY REFERENCING WESITES:

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Nicephore-Niepce

https://www.britannica.com/technology/camera-obscura-photography

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dagu/hd_dagu.htm

https://www.britannica.com/technology/calotype

https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2022/07/robert-cornelius-and-the-first-selfie/

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/julia-margaret-camerons-working-methods

Megan

This is well-researched and constructed…nicely done!

Always aim to add links / clips etc where you can to make blog posts interactive and cross -referenced