To embed your understanding of the origins of photography and its beginnings you’ll need to produce a blog post which outlines the major developments and practices. Some will have been covered in the documentary above but you also need to research and discover further information.

Your blog post must contain information about the following and keep it in its chronological order:

- Camera Obscura & Pinhole photography

- Nicephore Niepce & Heliography

- Louis Daguerre & Daguerreotype

- Henry Fox Talbot & Calotype

- Robert Cornelius & self-portraiture

- Julia Margeret Cameron & Pictorialism

- Henry Mullins & Carte-de-Visit

Each must contain dates, text and images relevant to each bullet point above. In total aim for about 1,000-2000 words.

Try and reference some of the sources that you have used either by incorporating direct quotes, paraphrasing or summarising of an idea, theory or concept, or historical fact.

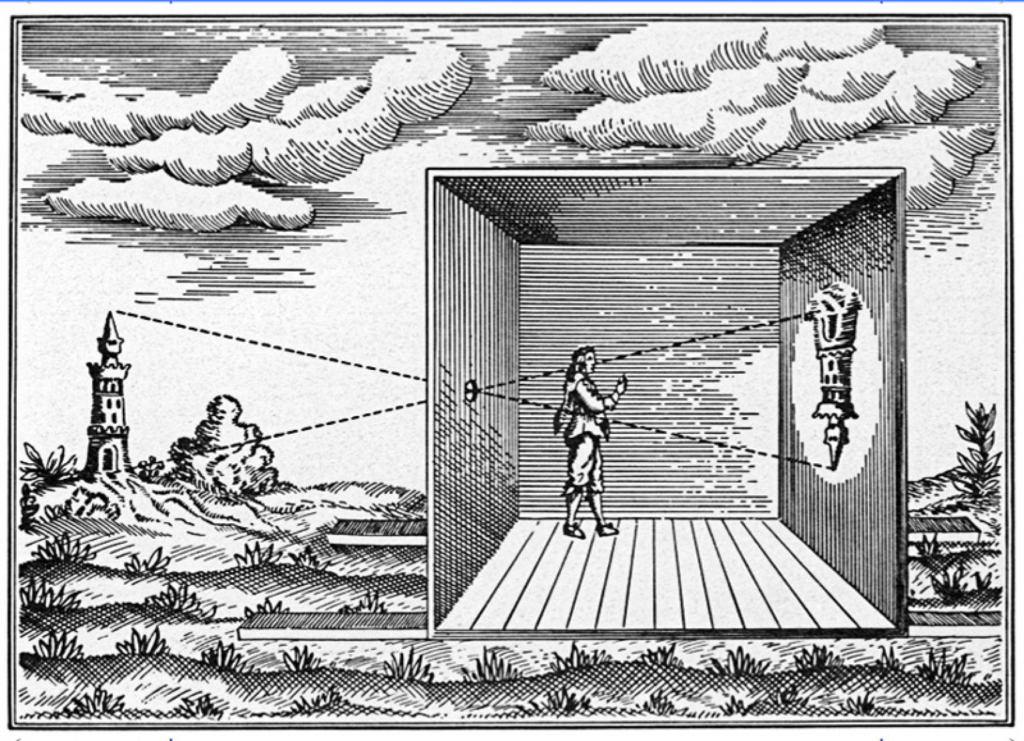

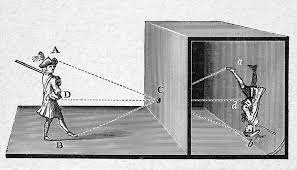

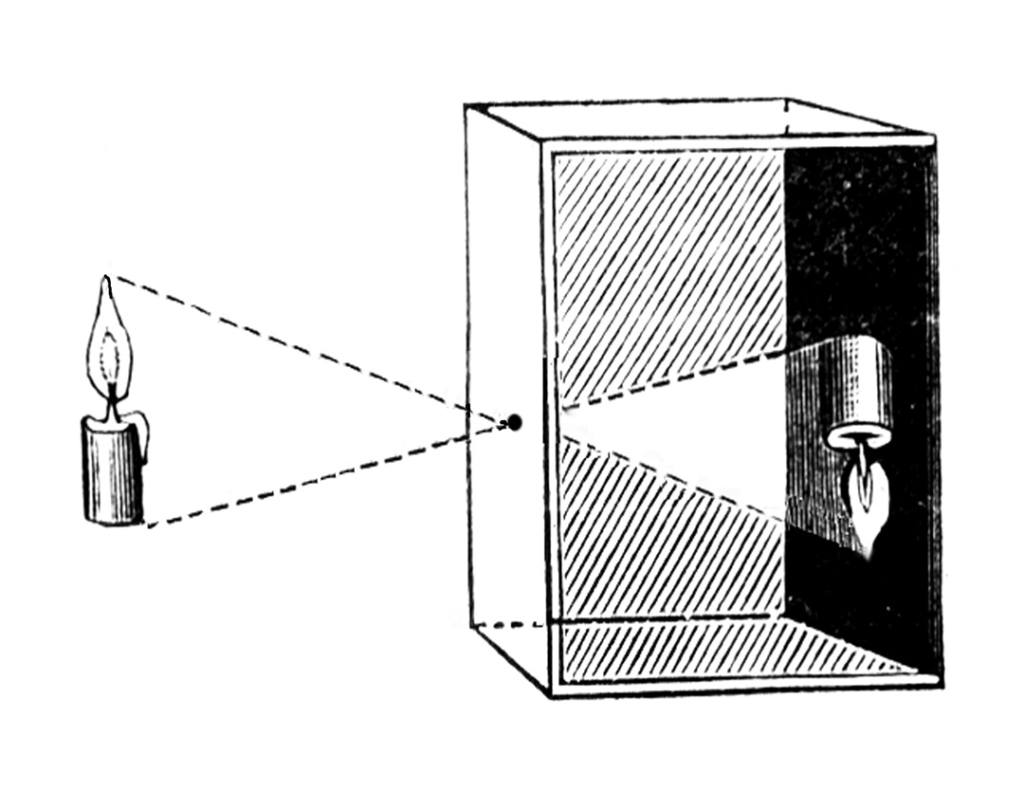

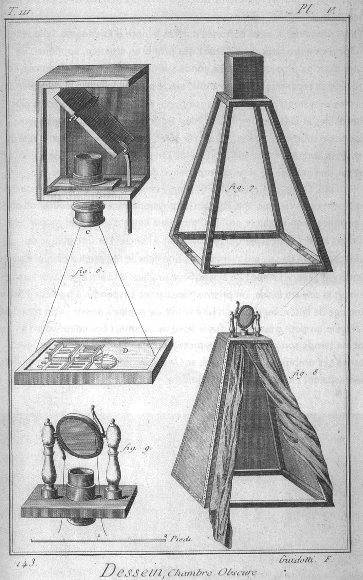

Camera Obscura & Pinhole photography

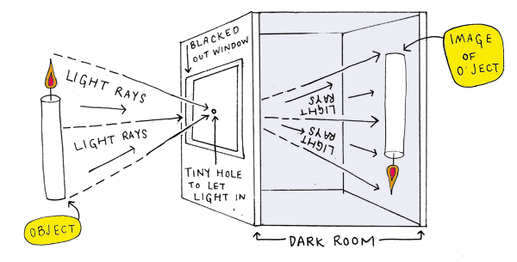

A pinhole camera is a simple camera without a lens but with a tiny aperture (the so-called pinhole)—effectively a light-proof box with a small hole in one side. Light from a scene passes through the aperture and projects an inverted image on the opposite side of the box, which is known as the camera obscura effect. The size of the images depends on the distance between the object and the pinhole.

The first mention of a camera obscura, from the Latin for ‘darkened room,’ was made in 1604 by German astronomer Johannes Kepler, not long after lenses had been invented for use in microscopes and telescopes in the Netherlands.

Nicephore Niepce & Heliography

Heliography is a photographic process that was invented by Nicéphore Niepce. In some cases – it is still used today (mainly for photo engraving). It was the process of Heliography that created the first and earliest known permanent photograph, taken from a nature scene.

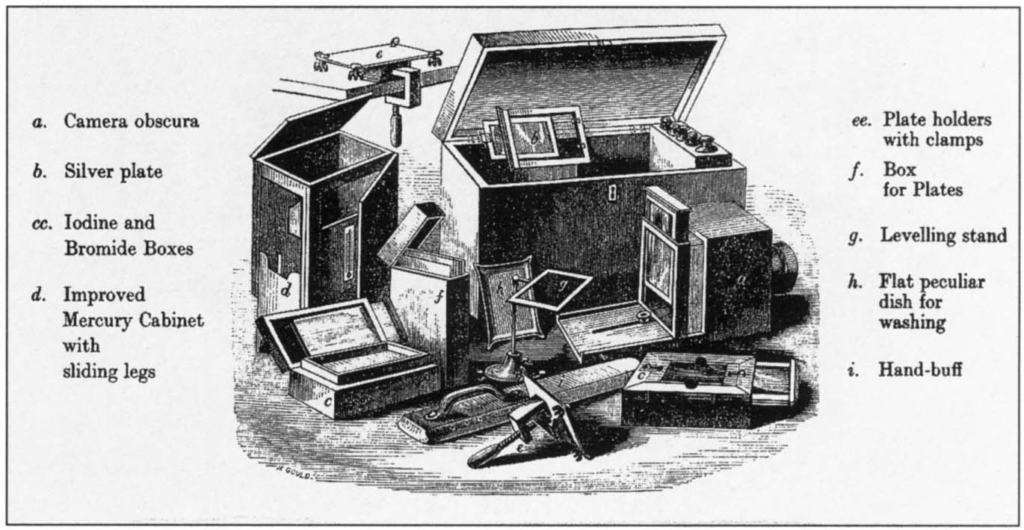

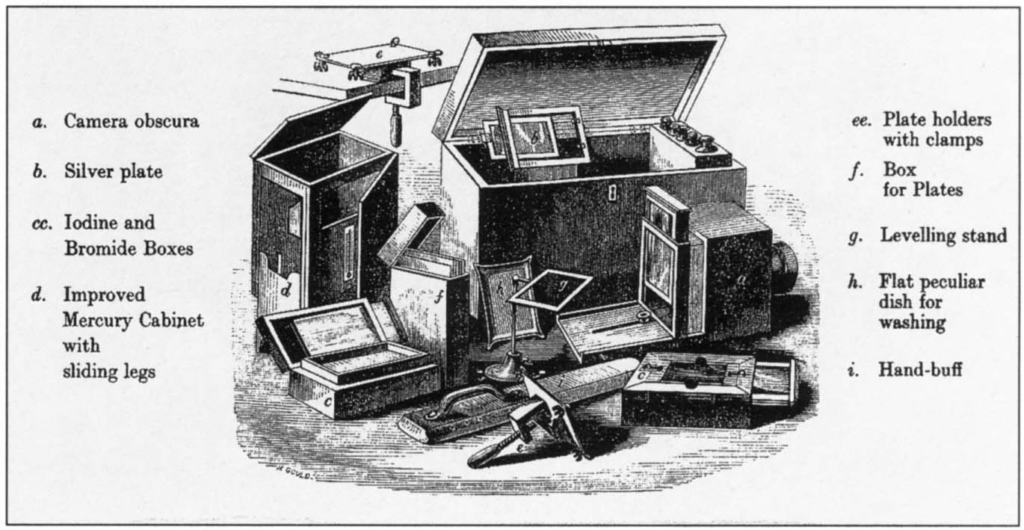

Louis Daguerre & Daguerreotype

The daguerreotype was the first commercially successful photographic process (1839-1860) in the history of photography. Named after the inventor, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, each daguerreotype is a unique image on a silvered copper plate.

In contrast to photographic paper, a daguerreotype is not flexible and is rather heavy. The daguerreotype is accurate, detailed and sharp. It has a mirror-like surface and is very fragile. Since the metal plate is extremely vulnerable, most daguerreotypes are presented in a special housing.

Numerous portrait studio’s opened their doors from 1840 onward. Daguerreotypes were very expensive, so only the wealthy could afford to have their portrait taken. Even though the portrait was the most popular subject, the daguerreotype was used to record many other images such as topographic and documentary subjects, antiquities, still lives, natural phenomena and remarkable events.

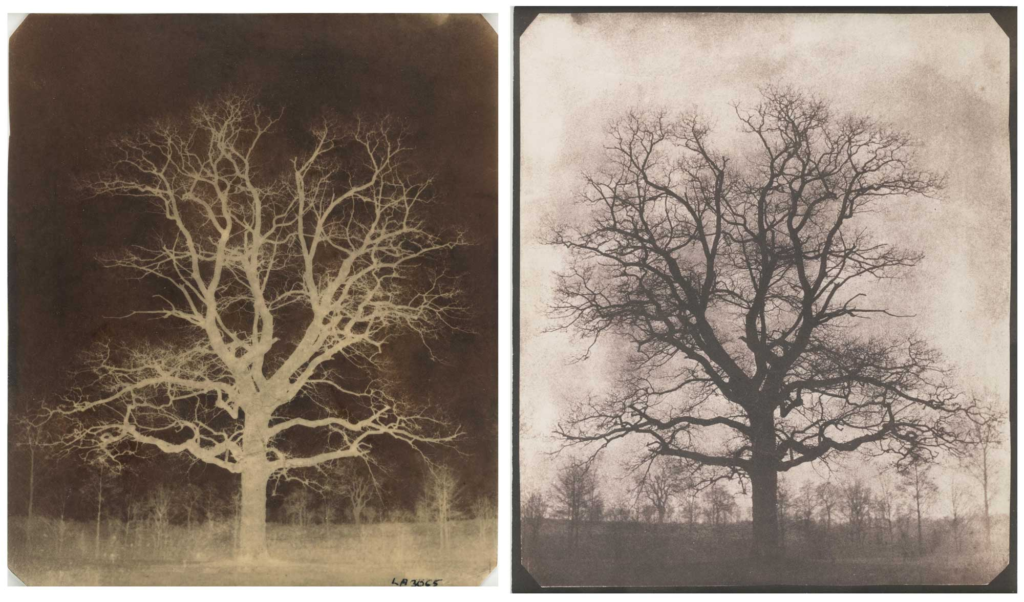

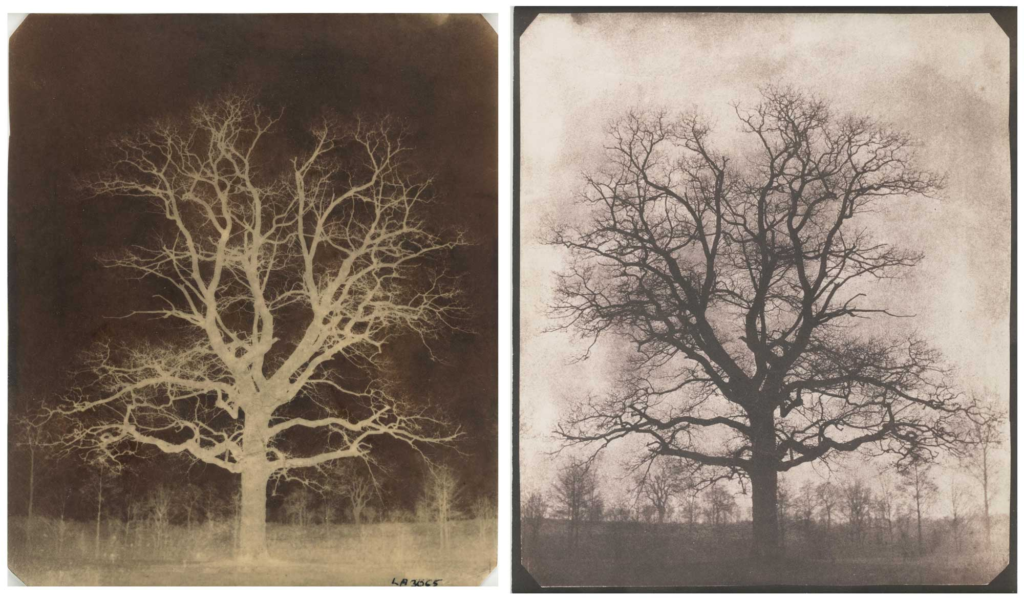

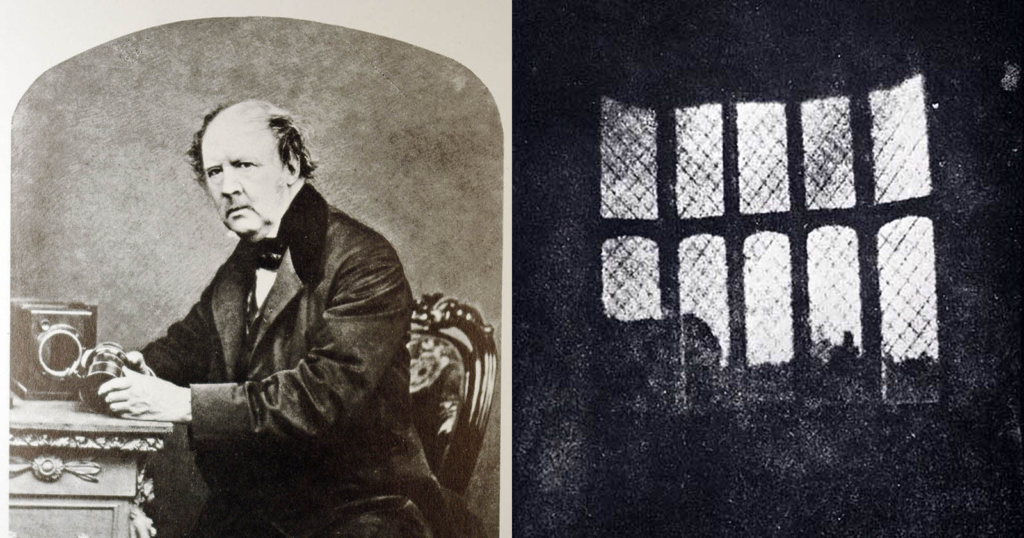

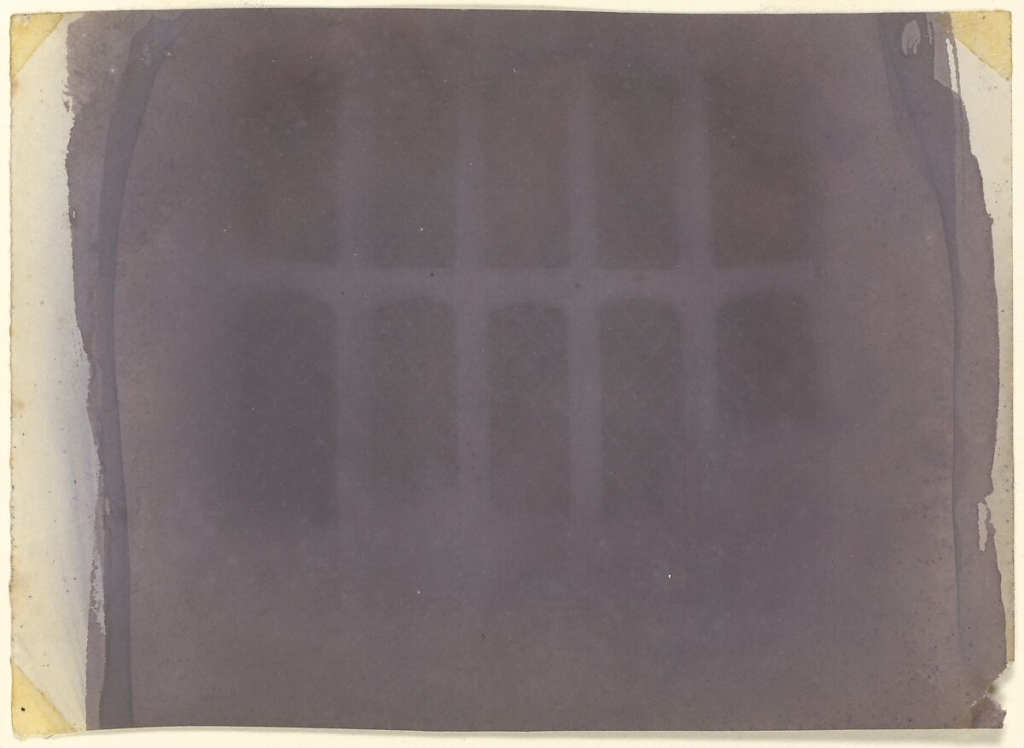

Henry Fox Talbot & Calotype

The calotype is sometimes called a “Talbotype.” This process uses a paper negative to make a print with a softer, less sharp image than the daguerreotype, but because a negative is produced, it is possible to make multiple copies. The image is contained in the fabric of the paper rather than on the surface, so the paper fibers tend to show through on the prints. The process was superceded in the 1850s by the collodion glass negative. Because of Talbot’s patent rights, relatively few calotypes were made in the United States.

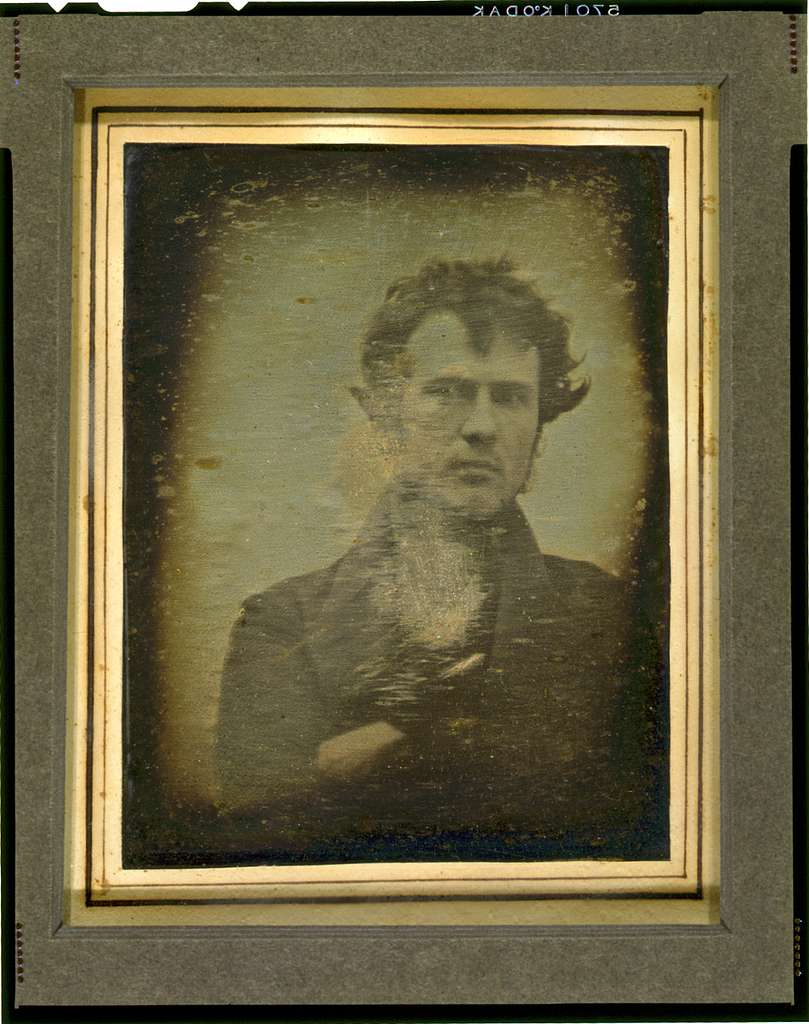

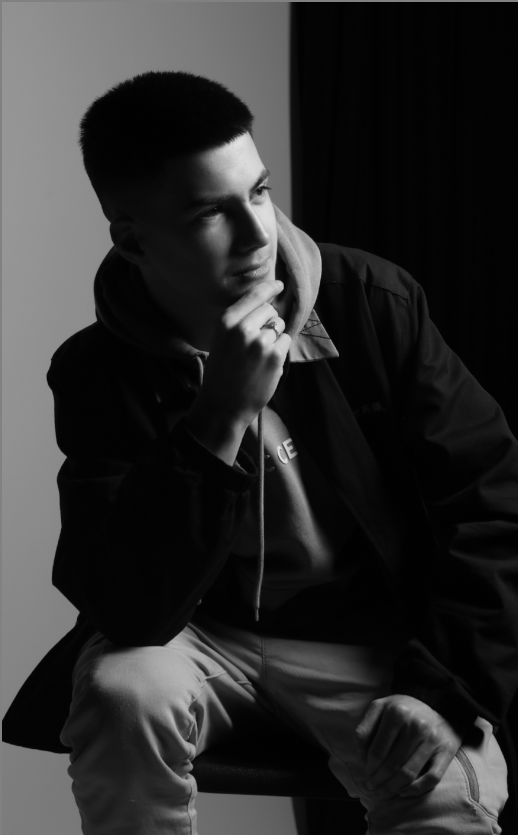

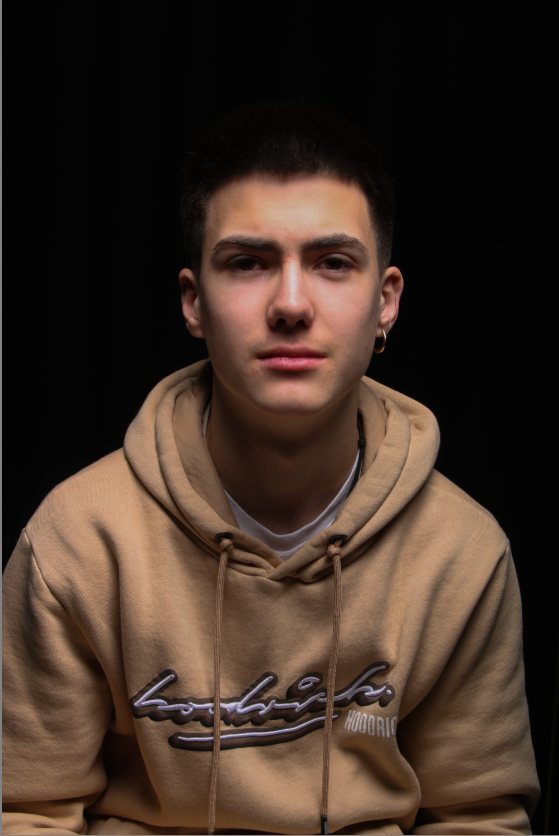

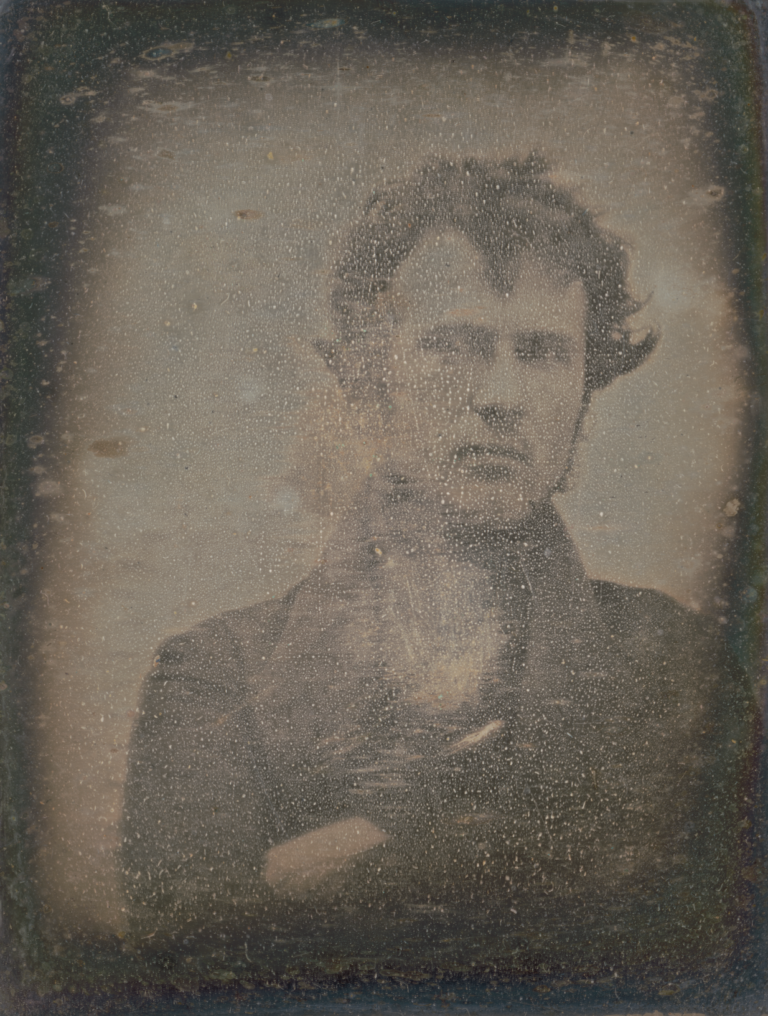

Robert Cornelius & self-portraiture

‘The first selfie‘ – Cornelius was 30 years old when he used the daguerreotype process, just after it was introduced, to capture the world’s first self portrait image in 1839. He stood solitary in his family’s yard in Philadelphia, late October, with his own makeshift camera. Its lens was fashioned from an opera glass. Making sure the daylight was perfect to expose his pre-prepared metal plate in the camera, he took the image. The exposure time was around 10-15 minutes, causing him to stand still for the whole exposure. Rachel Wetzel of the Library’s Conservation Division stated “Taking a portrait is astounding in 1839,”. This was the start of something new at the time, influencing the future generations and its photography.

Julia Margeret Cameron & Pictorialism

Julia Margaret Cameron (née Pattle; 11 June 1815 – 26 January 1879) was a British photographer who is considered one of the most important portraitists of the 19th century. She is known for her soft-focus close-ups of famous Victorian men and women, for illustrative images depicting characters from mythology, Christianity, and literature, and for sensitive portraits of men, women and children.

Pictorialism, an approach to photography that emphasizes beauty of subject matter, tonality, and composition rather than the documentation of reality.

The Pictorialist perspective was born in the late 1860s and held sway through the first decade of the 20th century. It approached the camera as a tool that, like the paintbrush and chisel, could be used to make an artistic statement. Thus photographs could have aesthetic value and be linked to the world of art expression.

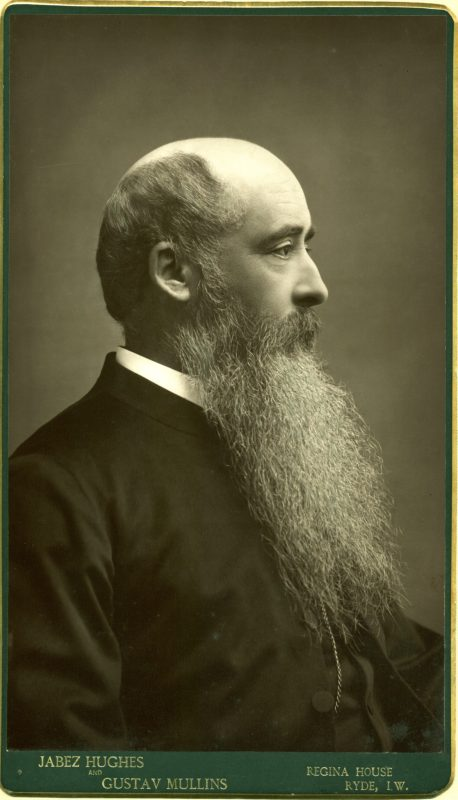

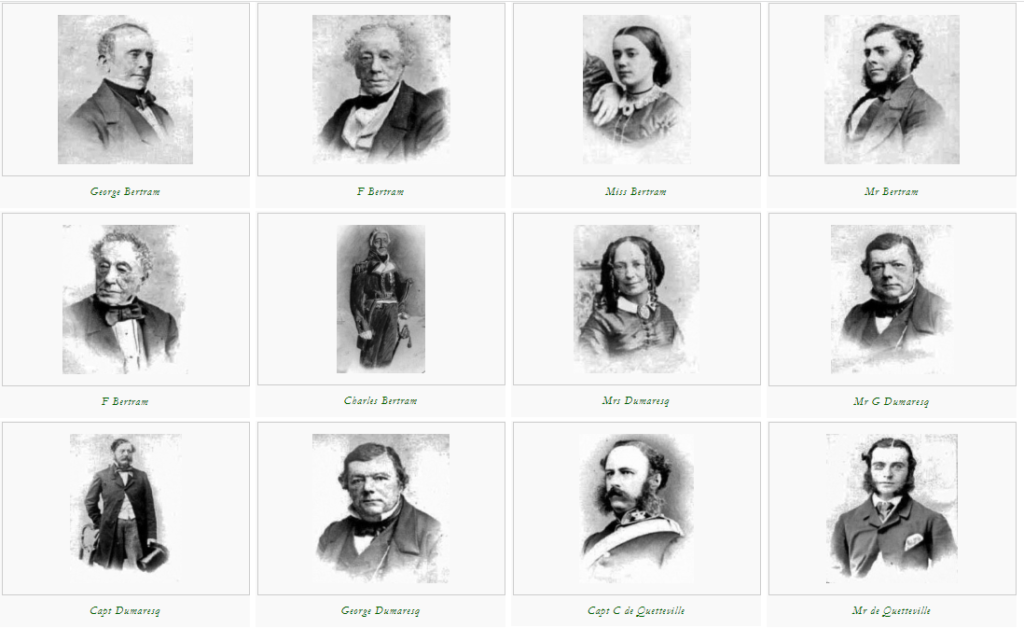

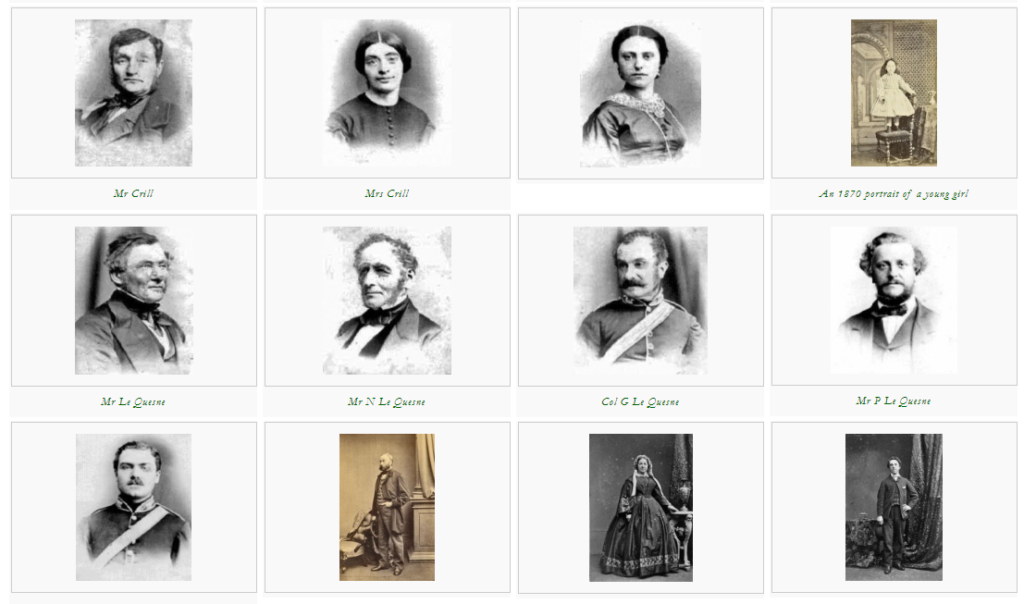

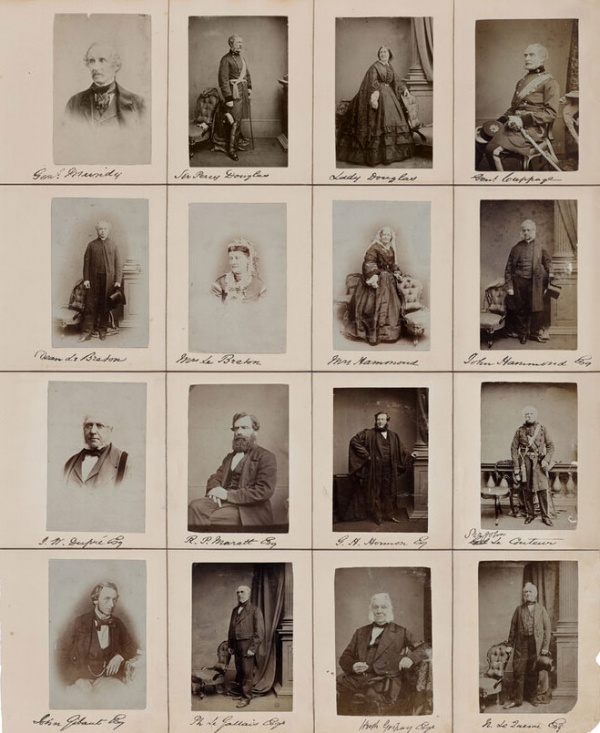

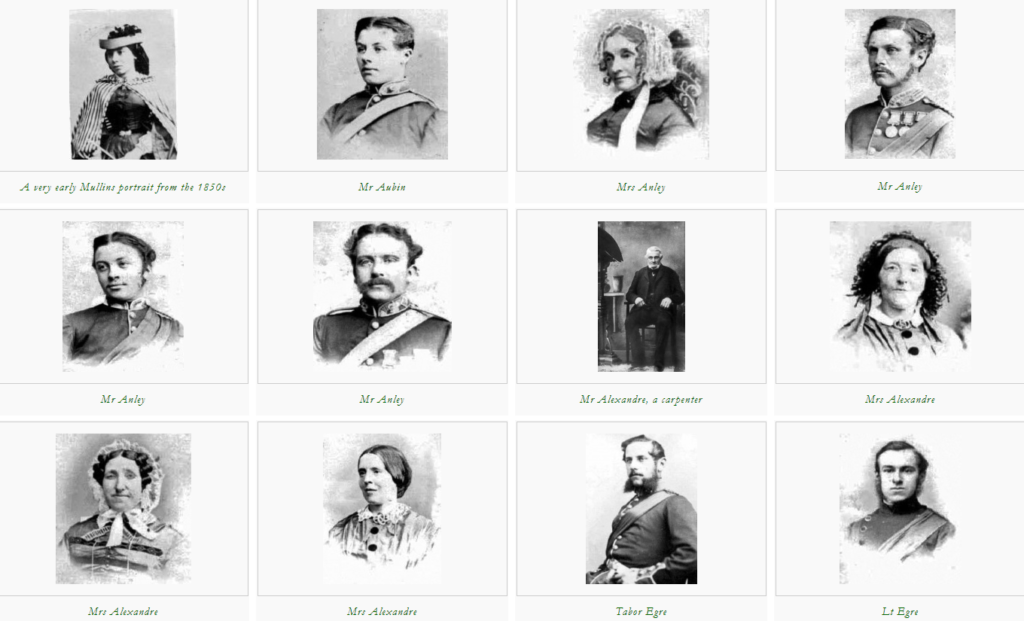

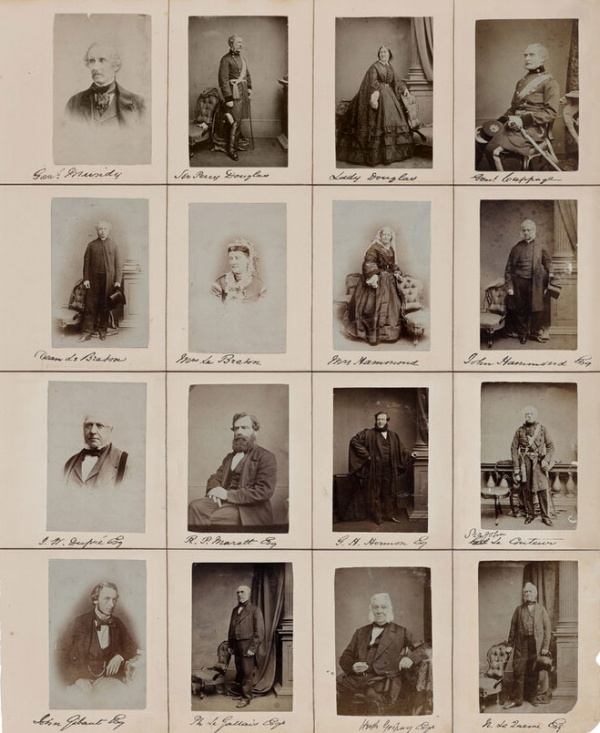

Henry Mullins & Carte-de-Visit

Moving to Jersey in 1848, Henry Mullins set up a studio known as the Royal Saloon at 7 Royal Square after previously working in London. Mullins became most famous for his cartes de visite and the photographic archive of La Société, that contains a large collection of 9600 images, the online archive holds photos mainly in sets of 16 photographs taken at a single sitting. As photographs were expensive at the time, Henry mainly photographed Jersey’s affluent and influential people. These include Dean Le Breton (he was ordained Deacon in 1839 and priest in 1840).

Mullins was in demand with officers of the Royal Militia Island of Jersey. It was very popular for them to have their portraits taken, including their families of the more important officers. Long hair, whiskers and beards were shown to be in fashion in the mid-1800s from Mullins’ photos. Due to this and the styling of the portraits, it is difficult to tell the difference between some of the officers in the portraits.

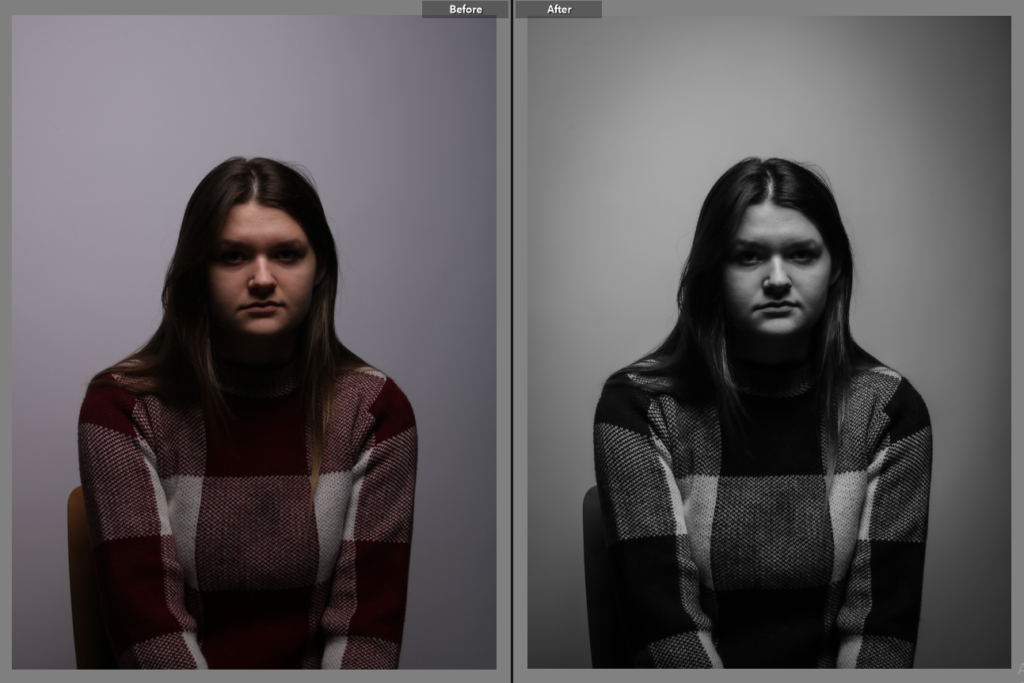

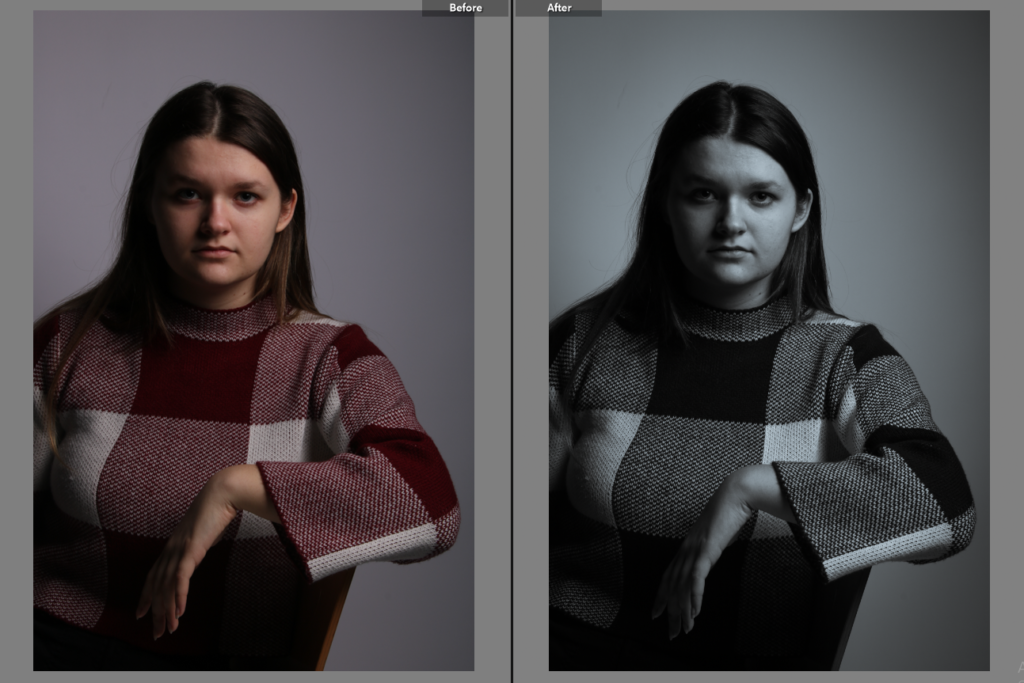

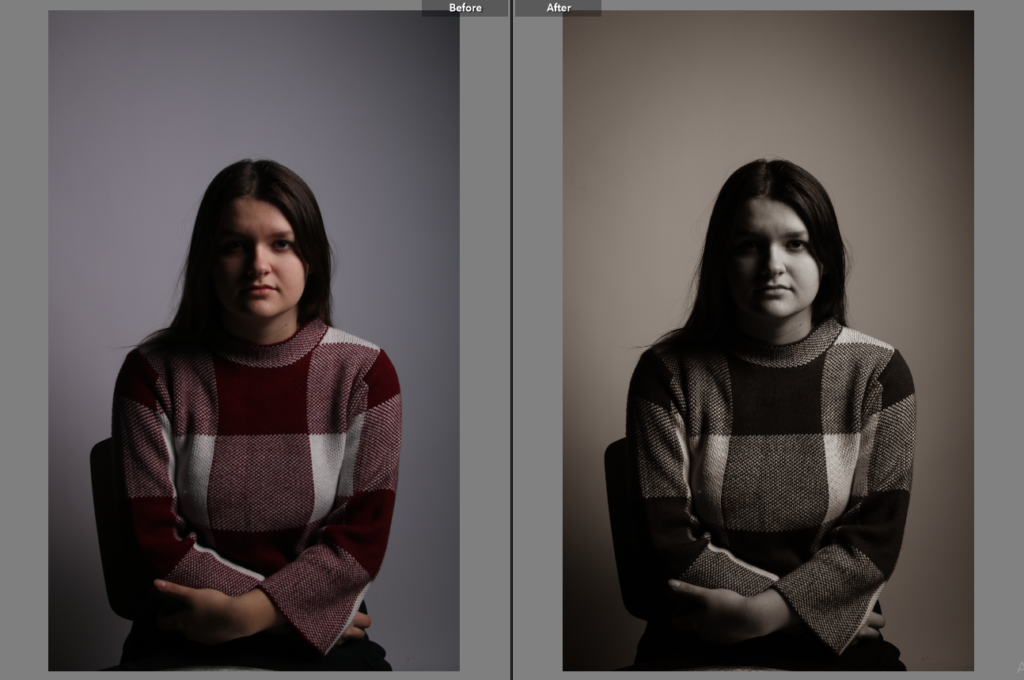

Henry Mullins / Michelle Sank on the social matrix, a juxtaposition is created by the editors between the historical photographs of Henry Mullins that date to the 1860’s, with the recent portraits by Michelle Sank. At first look of this book it appears to highlight the differences of the passing of 160 years in photography; warm toned black and white photographs created by wet collodion on glass with that of contemporary colour. The stilted poses required for the longer colloidal exposures versus the fluidity of the current instant moment.