ROMANTICISM

Writers and artists rejected the notion of the Enlightenment (1700-1800ish), which had sucked emotion from writing, politics, art, etc. However writers and artists in the Romantic period (1800-1900ish) favoured depicting emotions such as trepidation, horror, and wild untamed nature.

The ideals of these two intellectual movements were very different from one another. The Enlightenment thinkers believed very strongly in rationality and science. But, the Romantics rejected the whole idea of reason and science. They felt that a scientific worldview was cold and sterile.

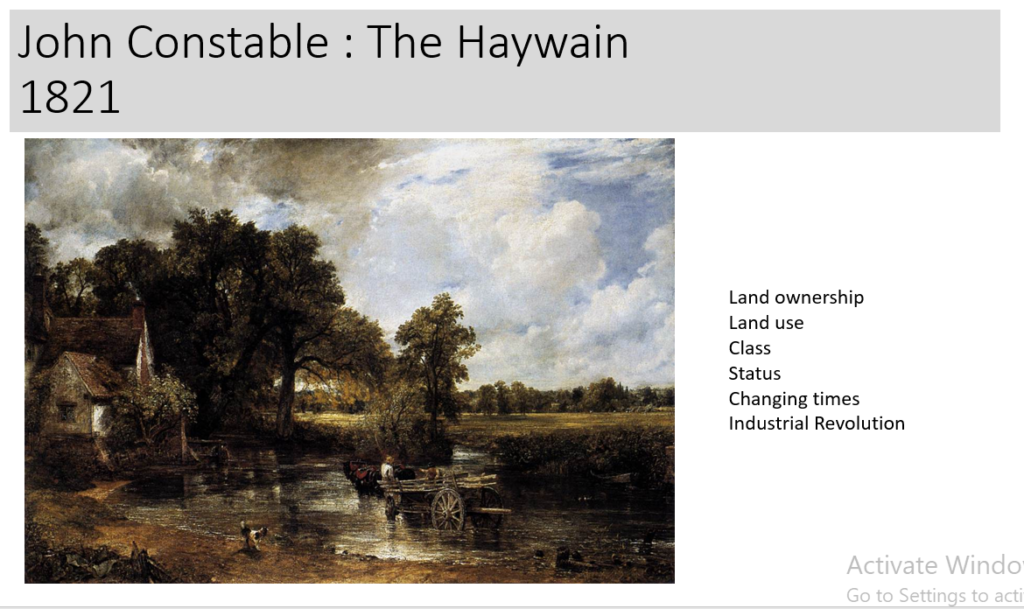

Romanticism itself could be seen as a rejection of the precepts of order, calm, harmony and rationality that typified Classicism in general and late 18th-century Neoclassicism in particular. Romanticism emphasized the individual, the subjective, the irrational, the imaginative, the personal, the spontaneous, the emotional, the visionary, and the transcendental. English Romantic landscape painting emerged in the works of J.M.W. Turner and John Constable. These artists emphasized transient and dramatic effects of light, atmosphere, and colour to portray a dynamic natural world capable of evoking awe and grandeur.

THE SUBLIME

Today the word is used for the most ordinary reasons, for a ‘sublime’ tennis shot or a ‘sublime’ evening. In the past however, it has a deeper meaning, pointing to the heights of something truly extraordinary, an ideal that artists have long pursued. Taking inspiration from the rediscovery of the work of the classical author the so-called ‘Pseudo-Longinus’ and from the writings of the philosopher Edmund Burke, British artists and writers on art have explored the problem of the sublime for over four hundred years.

Edmund Burke’s philosophical enquiry from 1757, saw connections of the sublime with this idea of romanticism; terror, awe and danger. He deduced that nature was the most sublime object and that it inflicted the most substantial feeling within people.

In modern society, photographers still use aspects of the sublime as a basis of landscape images, but are more compelled in responding to fears of increased industrialization, the threat of global destruction, and ecological disasters.

John Constable’s painting, ‘The Haywain’, shows different aspects of society during the Industrial Revolution. It shows a farmworker with a horse, trawling a haywain through a shallow river on a piece of farmland near a large house. However this raises questions like; “Does he own the land or is he working for someone? What is the surrounding area being used for? What is this farmworkers social class/status? What’s going on at the time?” In my opinions, this farmworker depicted in the painting works for someone who owns the land shown, or he is simply passing through someone else’s land on his way to market. But what I do, is that he does not own that house or land as during this era, people with enough money to own that much land would not be working it themselves. Therefore, I can assume that he is of quite a low status within British society. Then, there is the question of “What is the land being used for?” It simply looks like farmland or just an unused natural area of England, but the dark clouds in the top left of the image could suggest that further down-river, there could be a factory spewing fumes and pollution into the air and river, even though it isn’t shown in the image. This is most likely a correct assumption as 1821 is nearing the end of the British Industrial Revolution, and therefore factories were almost everywhere across the countryside and cities. The Industrial Revolution showed a drastic change to a new way of manufacturing consumer and trade goods on a massive scale. Therefore, perhaps Constable created this image as a way to capture what was left of the romantic settings before the modern age.

Good progress overall…evidence of hard work throughout

To be able to improve and highlight key areas of exceptional ability you must refer to the marking criteria and 10 Step Process too…here is the link https://hautlieucreative.co.uk/photo24al/2022/09/30/assessment-criteria-2/