Financial services are a highly important part of the economy of Jersey.

Jersey is considered to be an offshore financial centre and one of the most economically successful OFCs in the world. Jersey has the preconditions to be a microstate, but it is a self-governing Crown dependency of the UK. It is sometimes considered to be a tax haven. As of 2021, Jersey has received an AA-credit rating from Standard and Poors. The first ever bank in Jersey was established in 1796. The island was the first jurisdiction to bring in the world to bring trust and company service providers within a regulatory regime. Jersey-based financial organisations provide services to customers worldwide, including multi-currency banking, offshore mortgages and investment solutions. It is home to banking organisations from across the globe. In June 2020, it was reported that there were 13,450 jobs within this sector. According to Jersey Finance, a group which represents financial sector companies from the island, Jersey represents an extension of the City of London.

In 1961, banks began to establish offshore operations in Jersey to meet the growing demands of British customers. In the 1970s, Jersey authorities decided that bank licences should be limited to the top 500 global banks. The Jersey Joint Stock Bank was a Methodist concern in which the chapels and most of their members kept their money. There were two other joint stock banks, the Jersey Mercantile Union and the Channel Islands Bank. However, in 1862, Jean Le Neveu became the principal director in a new banking venture trading in St Helier as Le Neveu, Sorel et Cie. On 10 December 1863 a deed was passed in which the company acquired the premises of the English Union Bank, and it may have been as a result of that acquisition that the name English and Jersey Union Bank was coined, although Le Neveu, Sorel et Cie continued as the firm’s ‘social signature’ on their banknotes.

Jerseys decline is tourism

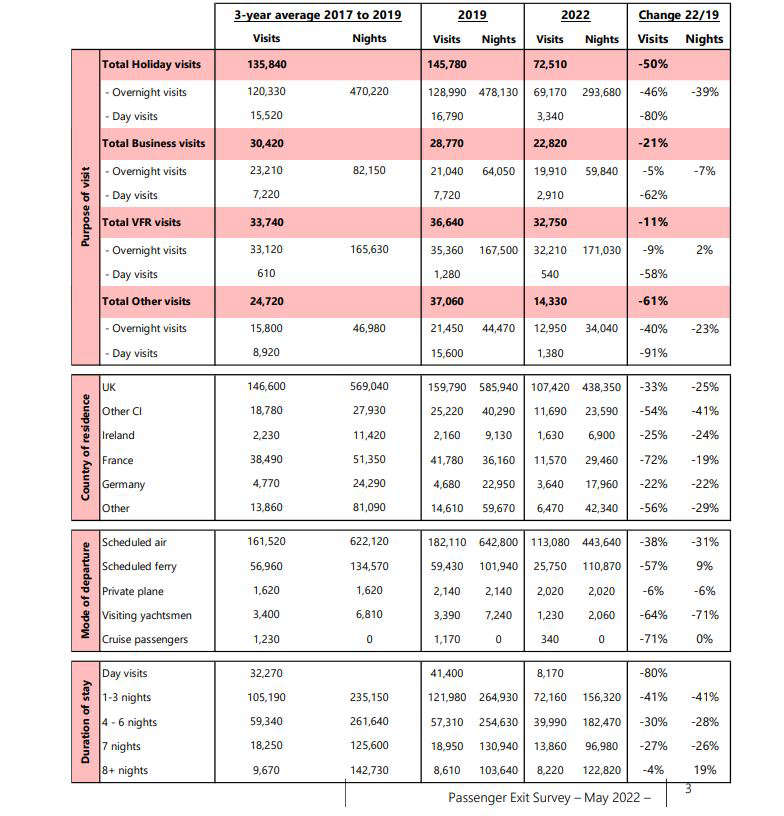

The number of people visiting Jersey between January and May 2022 is down by more than 40% on the same period in 2019. There were only 8,170 day visits in the first five months of this year – an 80% drop. Holiday visits are down by 50% and business trips have fallen by 21%. Visits from the UK have dropped by a third, while Channel Island visitor numbers have more than halved.

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the decline in tourism began, although a significant pointer would be the Seymour hotel groups plans for a large new hotel at Portelet in the 1980s. The was a large groundswell of local feeling that this would have a detrimental visual impact upon Portelet bay, but eventually planning permission was granted. By that time, however, the Seymour group had decided that the decline in the tourism market meant that the project was no longer viable, and decided not to go ahead with the building. In part, this can be seen as a consequence of the changing tourism market. Sea travel was not as popular, as lower air flights and package tour operators had opened up the continental market, and soon even further afield, as Laker Airlines provided low cost flights to America.

By the 1990s, there was a market decline in sea travel, and the UK route was no longer viable for two competing companies, and only Condor ferries remained. In an attempt to boost travellers, faster vessels, the so-called ‘wave piercers’ were brought into play, with the facility to take cars on a roll-on, roll-off basis; unfortunately, they were subject to the vagaries of local sea conditions, and could not sail in bad weather. The frequent cancellations and re-scheduling meant that a growing number holiday makers became disgruntled with the service, and their holiday memories of Jersey were not happy ones. Eventually, the newly formed Jersey Transport Authority was forced to take action, and putting the new contract out to tender ensured that Condor entered into a service level agreement; this involved reinstating one slow ferry service to provide a poor weather contingency. The year 2002 saw the Condor group up for sale to any prospective buyer.

By 2002, the Tourism committee seemed unable to define a clear market strategy, talking of concentrating on ‘infrastructure’, although precisely what this vague term meant was never apparent. The jewel in the tourist calendar, the ‘Battle of Flowers’, celebrating its 100th year was starved of funds; the Clipper race, which promoted Jersey throughout the world, had trouble gaining any sponsorship. The Tourism committee also seemed to be pinning their hopes on the planned hotel on the harbour waterfront boosting the lost visitor numbers, although there was no guarantee that this would be the case, and no indication how the obstacle of high air travel would be overcome or the high cost of living and recruitment of staff. Meanwhile, existing hoteliers called for firm monetary incentives rather than vague promises. No one has yet considered the UK strategy of tax incentives for ailing industries, although this might be considered a viable alternative.