Contact Sheets

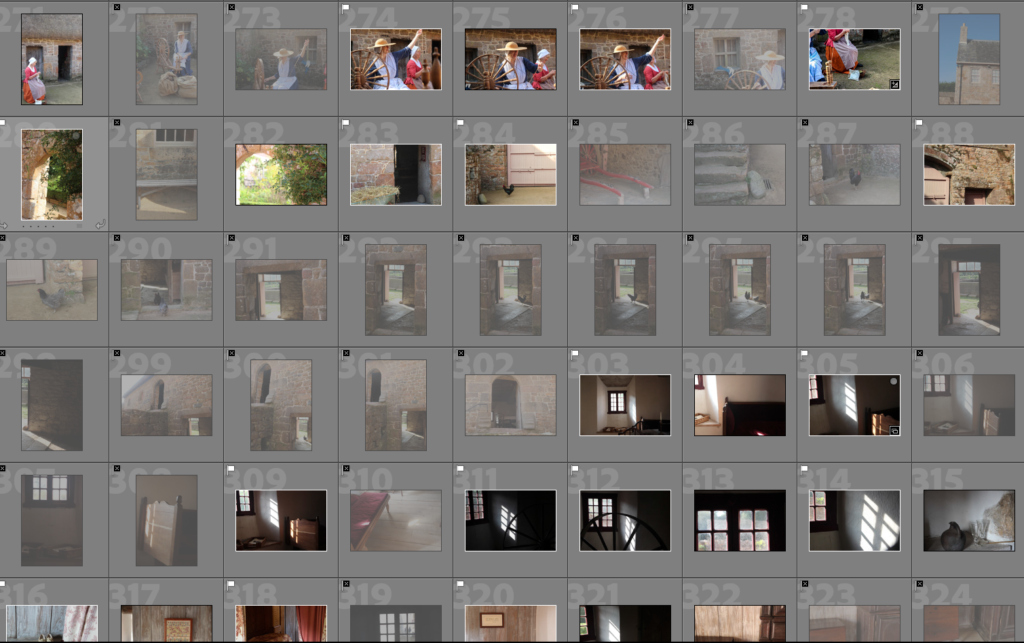

Using Adobe Lightroom Classic, I uploaded my pictures into a folder named Hamptonne. From this I went through my images, selecting images I did / didn’t like. I used the keys P and X to select or ignore certain images.

Using Adobe Lightroom Classic, I uploaded my pictures into a folder named Hamptonne. From this I went through my images, selecting images I did / didn’t like. I used the keys P and X to select or ignore certain images.

During the 18th century, power in Jersey was held in the hands of the Lemprière family. In 1750, Charles Lemprière was made Lieutenant Bailiff, and his brother Philippe was named Receiver-General.

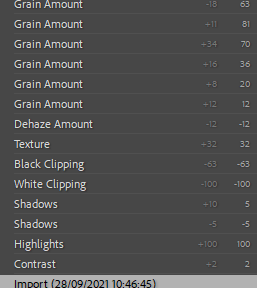

In 1767, people protested about the export of grain from Jersey. Anonymous threats were made against ship owners, a law was passed the following year to keep corn within the island. In august of the same year the court appealed this law, arguing that the levels of corn were plentiful so export was not detrimental. There was suspicion that this appeal was a ploy to raise the price of wheat, which would be beneficial to the rich – many of them had ‘rentes’ owed to them on properties that were payable in wheat. As major landowners, the Lemprière family stood to profit hugely.

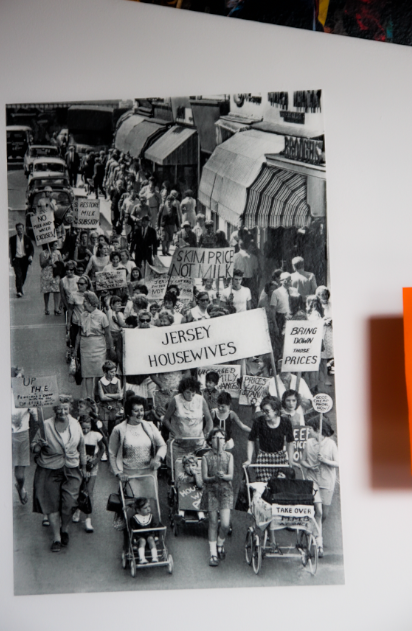

Later in this summer, a ship loaded with corn for exportation was raided by a group of women who demanded that the sailors unload their cargo and sell it in the island – “Let us die on the spot, rather than by languishing in famine, God hath given us corn, and we will keep it, in spite of the Lemprieres, and the court, for if we trust to them they will starve us.”

Then, on the 28th september of the same year, a Court called the Assize d’Héritage was sitting, hearing cases relating to property disputes. The Lieutenant Bailiff, Charles Lemprière, sat as the Head of the Court. Meanwhile, a group of disgruntled individuals from Trinity, St Martin, St John, St Lawrence and St Saviour marched towards Town where their numbers were swelled by residents of St Helier. The group was met at the door of the Royal Court and was urged to disperse and send its demands in a more respectful manner. However, the crowd forced its way into the Court Room armed with clubs and sticks. Inside, they ordered that their demands be written down in the Court book.

That the price of wheat be lowered and set at 20 sols per cabot.

• That foreigners be ejected from the Island.

• That his Majesty’s tithes be reduced to 20 sols per vergée.

• That the value of the liard coin be set to 4 per sol.

• That there should be a limit on the sales tax.

• That seigneurs stop enjoying the practice of champart (the right to every twelfth sheaf of corn or bundle of flax).

• That seigneurs end the right of ‘Jouir des Successions’(the right to enjoy anyone’s estate for a year and a day if they die without heirs).

• That branchage fines could no longer be imposed.

• That Rectors could no longer charge tithes except on apples.

• That charges against Captain Nicholas Fiott be dropped and that he be allowed to return to the Island without an inquiry.

• That the Customs’ House officers be ejected.

Following the riots, on 6 October, a meeting of the States of Jersey was held at the Castle when it was agreed that Charles Lemprière, together with two Jurats, and Philippe Lemprière, the Attorney General, would journey to London in order to present their difficulties to the Privy Council, representing the Crown.

At first, the Privy Council was outraged by their reports and commanded that the demands of the rioters be erased from the Court records. On 1 November, a Royal Pardon and a reward of £100 was offered to any rioters who named the ringleaders. After the full situation in the Island became clear, the protestors were eventually pardoned. The corn riots had helped Jersey to become a fairer society at the time, and have an influence on how reform was dealt with from then onwards.

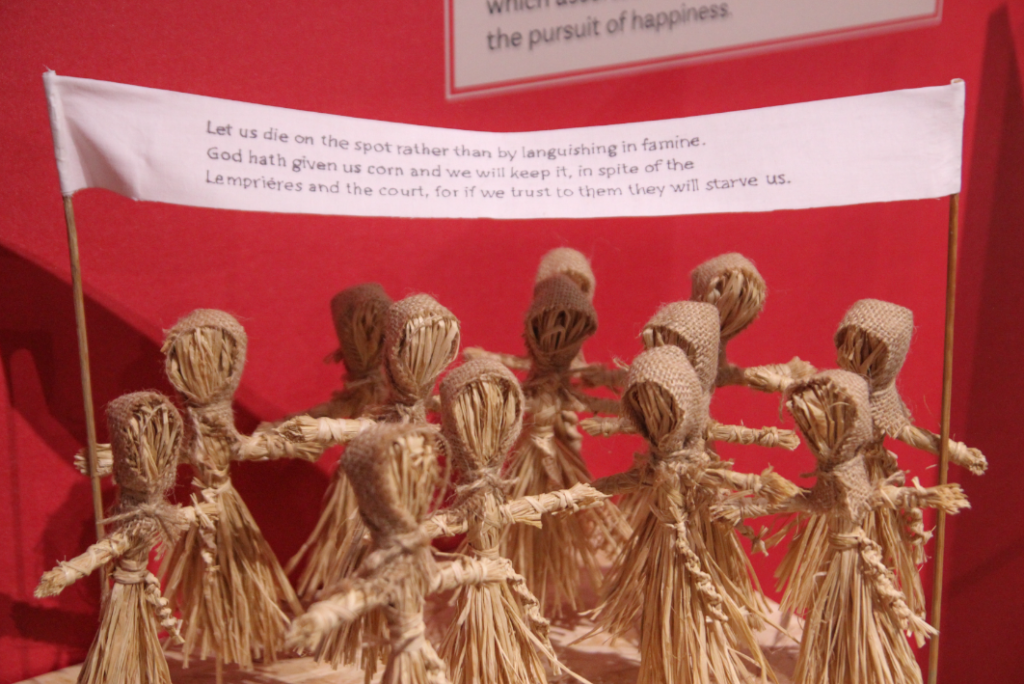

In the 1970s, a growing population and increasing numbers of holiday makers put large pressure on Jersey’s water resources. In 1976, during a summer of droughts and hose pipe bans, the Jersey New Waterworks Company announced plans to flood Queen’s Valley and create a new reservoir. Thousands of islanders supported 2 anti-flooding groups:Concern, Friends of Queen’s Valley, and Save our Valley, arguing flooding the Valley was not a solution. They suggested capping the island’s population at 80,000, installing water meters and using more desalinated water.

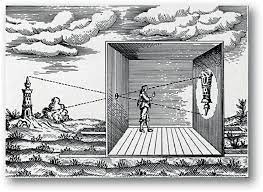

A camera obscure is a darkened room with a small hole or lens at one side, through an image is projected onto a wall or table opposite. Camera Obscuras with a lens in the opening have been used since the second half of the 16th century and became popular as help for drawing or painting.

The camera obscura was also used to study eclipses without the risk of damaging the eyes by looking directly at the sun. When it was used as a drawing aid, it helped tracing the projected scene to create a highly accurate picture.

Nicephore Niepce was a French inventor. He was led to the art of photography by his interest in the new art of Lithography. However he lacked the artistic ability for these. Letters to his sister-in-law around 1816 indicate that he had managed to capture small camera images on paper using silver chloride, with him apparently the first to have any success at all in such an attempt, but the results were negatives, dark where they should be light and vice versa, and he could find no way to stop them from darkening all over when brought into the light for viewing.

Niepce used a coating of bitumen of Judea to make the first permanent camera photographs. The bitumen was hardened where it was exposed to light and the unhardened portion was then removed with a solvent. A camera exposure lasting for hours or days was required. Niépce and Daguerre later refined this process, but unacceptably long exposures were still needed.

Daguerre experimented for years with increasing the sharpness of the lens in the camera obscura and working at discovering the reaction of various light-sensitive materials when applied to different surfaces. With Nicephore Niepce, who was engaged in similar efforts, he worked on this. They worked at permanently capturing the images they saw in the camera obscura, and critiqued each other’s work with each attempt. It was essential that they prepare a medium to be sensitive to light, using a lens and light to form an image upon it, but then making that same medium insensitive to further exposure so that the resulting image could be viewed in light without harming it. When Niepce passed away in 1833, and Daguerre continued some correspondence with his son, Isidore.

By 1835, word got around Paris that the city’s favourite master of illusion and light had discovered a new way to enchant the eye. In January of 1839, the invention of a photographic system that would fix the image caught in the camera obscura was formally announced in the London periodical The Athenaeum.

Louis Daguerre called his invention “daguerreotype.” His method, which he disclosed to the public late in the summer of 1839, consisted of treating silver-plated copper sheets with iodine to make them sensitive to light, then exposing them in a camera and “developing” the images with warm mercury vapor. The fumes from the mercury vapor combined with the silver to produce an image. The plate was washed with a saline solution to prevent further exposure.

Daguerreotypes offered clarity and a sense of realism that no other painting had been able to capture before. By mid-1850’s, millions of daguerreotypes had been made to document almost every aspect of life and death.

Shortly after the invention of the daguerrotype was announced in 1839, Talbot asserted priority of invention based on experiments he had began in 1834. At a meeting of the Royal Institution on 25 January 1839, Talbot exhibited several paper photographs he had made. These showed his ways of chemically stabilising his results, making them insensitive to further exposure that direct sunlight could be used to imprint the negative image produced into the camera, onto another sheet of salted paper – creating a positive.

The calotype, was then introduced in 1841 – it used paper coated with silver oxide. The calotype process produced a translucent original negative image from which multiple positives could be made by simple contact printing. This gave it an important advantage over the daguerreotype process, which produced an opaque original positive that could be duplicated only by copying it with a camera.

Long before his discovery of the dry gelatin photographic emulsion, Maddox was prominent in what was called photomicrography – photographing minute organisms under the microscope. The eminent photomicrographer of the day, Lionel S. Beale, included as a frontispiece images made by Maddox in his manual ‘How to work with the Microscope’.

The Gelatin or Dry Plate photographic process was invented in 1871 by Maddox: This involved the coating of glass photographic plates with a light sensitive gelatin emulsion and allowing them to dry prior to use. This made for a much more practical process than the wet plate process as the plate could be transported, exposed and then processed at a later date rather than having to coat, expose and process the plate in one sitting. The gelatin dry plate process technique was developed and eventually led to the roll film process.

In 1884, Eastman patented the first film in roll form to prove practical and useful. He had been experimenting at home to develop it. In 1888, he developed the Kodak camera (“Kodak” being a word Eastman created), which was the first camera designed to use roll film. He coined the advertising slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest” which quickly became popular among customers. In 1889 he first offered film stock, and by 1896 became the leading supplier of film stock internationally. He incorporated his company under the name Eastman Kodak, in 1892. As film stock became standardized, Eastman continued to lead in innovations. Refinements in colored film stock continued after his death.

The Kodak Brownie was a series of cameras made by Eastman. They were introduced in 1900 – it was a basic cardboard box camera with a simple meniscus lens that took 2 and 1/4 square pictures on a 117 roll film. It was made and marketed for Kodak roll films, and because of its simple controls and initial price of 1$ (31$ in today’s money.) it became very popular.

Print photography is the practice of utilising chemically sensitive paper that’s exposed to a negative, a transparency or a digital image from a printer or similar device. Alternatively, the negative or transparency may be placed on top of the paper and directly exposed which creates a contact print. Digital photos, however are printed commonly on pain paper, for example by a colour printer.

Film photography is a type of photography that uses chemical processes too capture an image, typically on paper, film or a hard plate. These analog processes were the only methods available to photographers for more than a century prior to the invention of digital photography.

Digital photography uses cameras containing arrays of electronic photodetectors to produce images focused by a lens, as opposed to ask exposure on film. The images captured are digitised and stored as a computer file ready for further digital processing, viewing, electronic publishing or digital printing,

Cyanotypes are an alternative photographic process that rely on the chemical prosperities of two iron compounds – ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide.

Formulas of these two iron compounds of are mixed together to form a citrine coloured solution. The solution can then be painted onto a surface such as paper or cotton. Once the material is dry, things such as flowers and leaves are placed onto the material into the desired composition. After this, the material is left in the sun for up to 2 minutes to create a bleached outline of the shapes and objects placed on the material. Next, the material is dipped in water, and should be left to dry in a dark place so that the material doesn’t auto-expose.

The cyanotype was invented by Sir John Herschel in 1842. His first intention was to experiment with the effect of light on iron compounds. He discovered that the exposure to light turned a combination of ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide blue. This method was then used for printing copies of photographic negatives. Later on, photographic practitioners such as William Henry Fox Talbot, Anna Atkins and Henry Bosse took up the process.

Anna Atkins applied the process of cyanotypes, invented by Sir Herschel. She applied this process to algae, making cyanotype photograms, that were contact printed. She did this by placing uncounted, dried seaward directly onto the cyanotype paper. Anna self published her photograms in the first instalment ofPhotographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions in October 1843. She planned to provide illustrations to William Harvey’s Manual of British Algae which had been published in 1841. Although privately published, with a limited number of copies, and with handwritten text, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions is considered the first book illustrated with photographic images. Atkins kept the algae, ferns, and other plants she used in her work and in 1865, donated the collection to the British Museum. She died in 1871 of “paralysis, rheumatism, and exhaustion” at the age of 72.

After cyanotypes mostly disappeared through both world wars, the 1950 and 60s saw a resurgence of amateur photography and fine art. The new discovery of these techniques respited in their development to scientific copies to more experimental examples. Eg: Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil’s collaborative cyanotypes.

In the modern era of photography, cyanotypes are produced more and more using mixed mediums, such as clothing, as well as large instillations.

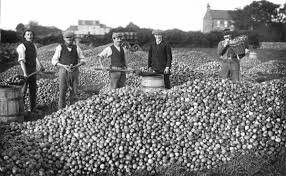

Hamptonne Country Life Museum gives the visitor a unique insight into the rural life carried on in Jersey for centuries. Dating back to the 15th Century the house and farm are perfect for discovering the rural history of Jersey. Explore the different houses which make up Hamptonne, find out more about Jersey’s history of cider making in the cider barn and wander through the cider apple orchard and meet the Hamptonne calves, lambs, chickens and piglets in the traditional farmstead.

The Hamptonne farm complex takes its name from Laurens Hamptonne, who purchased it in 1633. The property is also known as ‘La Patente’, as is the name of one of the roads that passes it, after the Grants by Letters Patent received by its owner Richard Langlois in 1445, and by King Charles II to Laurens Hamptonne in 1649.

Hamptonne’s support of the struggling and exiled King Charles II resulted in 2 grants – One preserved the integrity of the property in perpetuity – it could not be broken up into parts (partages) and split among family members, but would be inherited by the eldest child. Another permitted Hamptonne to rebuild the ruined Colombier (dovecote) originally granted to Richard Langlois. In normal circumstances, such buildings could only be built by Jersey Seigneurs (Lords or holders of a fief.). The Colombier is located to the south-east, slightly beyond the current boundaries of the Museum. This may not have been a source of local popularity for Hamptonne.

The Hamptonne site’s shape is square. It has many different buildings and houses constructed in different periods. The farm has medieval origins, but as the centuries have continued, owners have made improvements of the living quarters. The main buildings are therefore named after the Langlois, Hamptonne and Syvret families, who lived here between 15th and 19th centuries.

When you exit the shop, you enter the North Courtyard along the side of which runs the Northern Range – a row of 19th century farm buildings constructed to meet the specifications of the agriculture industry, its vehicles and horses. It include a Labourers Cottage, Coach House, Bake House & Laundry, and Stables. Facing the Stables is a glazed barn in which important farming devices and implements are displayed. There is a walled vegetable and herb garden to the east, beyond which is the Hamptonne Playground and Cider Apple Orchard.

Further on, to the south there is Langlois House. This building is comprised of a barn, with cows, and stables on the lower level. Above the animal barn there is a parlour and also a bedroom. In the south west corner there’s an arched stone gateway that allows access to the road.

To the west is the Cider making house or ‘presser’ with a granite apple press and crusher. This is where cider is made every October, a key part of Hamptonne’s heritage. To the south end of this row is Syvret house. This house is presented as the home of a tenant farmer in 1948, with many interactive stories in certain areas of the house. It consists of a kitchen, parlour, two bedrooms, and a small cabinet.

To the east of the farm buildings is the orchard. Within this orchard there are many cider apple trees, which are renowned for their sweet, bitter and sharp flavours to use within cider making. There is then footpath that guides you through the orchard, towards a small wooded area. Within the farm’s fully working era, the wooded area would have provided an important resource for collecting wood. This would have been crucial for fuel as well as building materials, as well as wildlife. The path then continues to the grazing meadow, where sheep or cows often reside. Every year, there is a cider festival at Hamptonne farm, remembering the ancient way of making the drink, with Jersey’s heritage at its heart.

The goodwyf, during the 16th century, was the housekeeper of Hamptonne house. She looked after the house of her master, Monsieur Laurens Hamptonne. duties included cleaning, cooking, and tending to the fire. She makes soap, herbal remedies and makeup and candles.She was very respectful of her employer, as he was a well educated and respected man. She is captured in pictures with a sullen facial expression as in the era of her employment women posed for hours in neutral facial expressions.

Furthermore, the characters of two ladies working on the spinning wheel and loom recreate the ancient art of spinning wool on a loom. They speak about Jersey’s involvement with the exportation of stockings during the Tudor era, the laws imposed around it at the time, and how it helped Jersey’s economy.

Tom Kennedy is a Jersey photographer, who is influenced by the Dutch Masters paintings of the 17th century, including Rembrandt and Vermeer.

His work with living history characters focuses on the use of natural soft lighting, sometimes with the help of a little artificial lighting. He uses subtle light to create beautiful soft shadows on his subjects’ faces, capturing them in their natural environments from the time period of the characters.

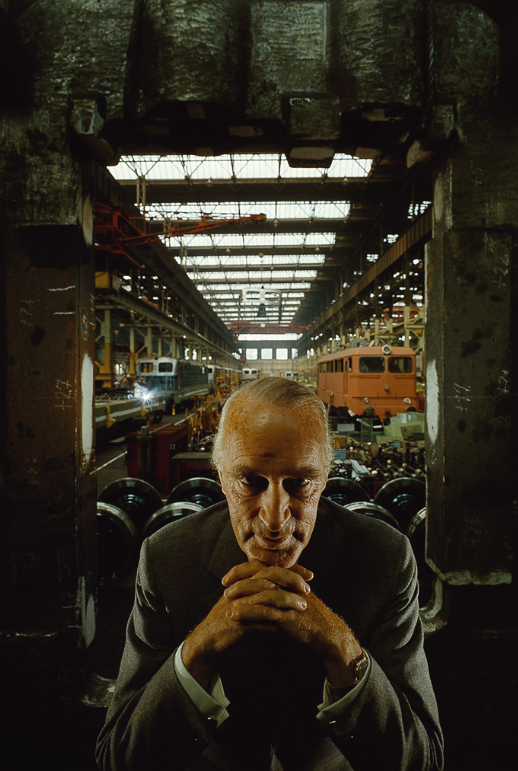

The lighting within this image is more underexposed, rich and dark towards the bottom of the image, but towards the top of the image the lighting is harsh and artificial. In the area of windows in the middle of the image, there is an area of high overexposure. The white balance is warm, and there is an orange tone to the image. This shot is shot in portrait, with a slightly blurry texture, and slightly fine grain. This means that the light sensitivity was higher, creating this grain.

The tone in this image is rich and dark, however with high light points in the middle section of windows. The angle in which the photo is taken creates a triangle shape leading towards the background. This creates natural leading lines within the image, drawing the eye from the subject of the mage to the background of the factory. The doorway above the subject’s head creates a natural frame for this dramatic portrait. There is slight shadow on the subject’s face, but deep underexposure, and tones of black and orange on the middle of his face. The use of repeated rectangle and square shapes in the construction of the factory creates a sense of a uniformed and rigid environment, and creates an organised composition.

Alfred Krupp, the subject of this picture, was a factory boss in WWII. He was very controversial figure in post war Germany, due to his encouragement and use of forced and child labour in his factories during the war. He sourced his workers from concentration camps, and forced these victims to work in horrific and dangerous conditions, making weapons for the German army. He was charged with crimes against humanity, in 1951, and died in 1967.

I believe that the idea behind this image is to showcase the power of money and industrial strength that was behind World War II.

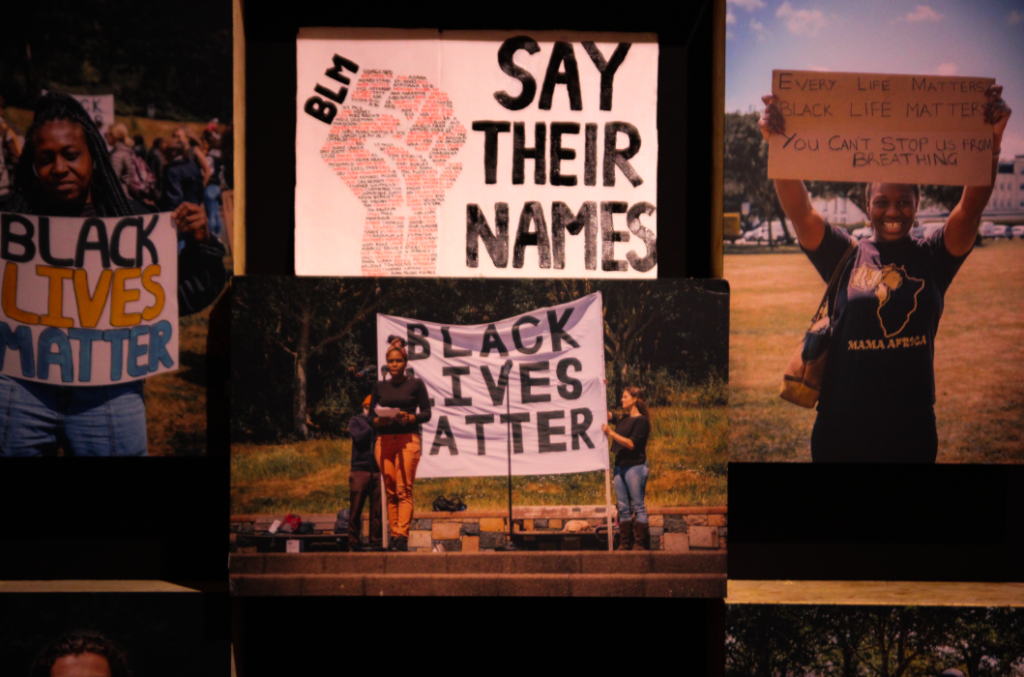

Photography is medium that allows news to be spread, and new ideas to be shared eg: Photojournalism, documentary photography, and ways of advertising: fashion photography as well as product photography. Photography is important for this reason: it allows voices that would otherwise silent to ber heard, and different perspectives and points of view to be voiced.

Photography can be used to tell stories, as well as provoking memories. People make photographs to capture memories as well as to document a time, or place. The passing of time is a common idea that photographers seek to portray: for example age, or historic moments. To be a good photographer, you need lots of patience, as well as an eye for different shapes and symmetry.

Unfortunately, in today’s digital age, images can be heavily manipulated, as well as only telling one side of a story. Tools such as cropping, photo manipulation and different angles allow photos to be twisted and changed to show only one view, or be made to look older / newer than reality. This can cause issues in the world of politics and social media, as well as current affairs and news.

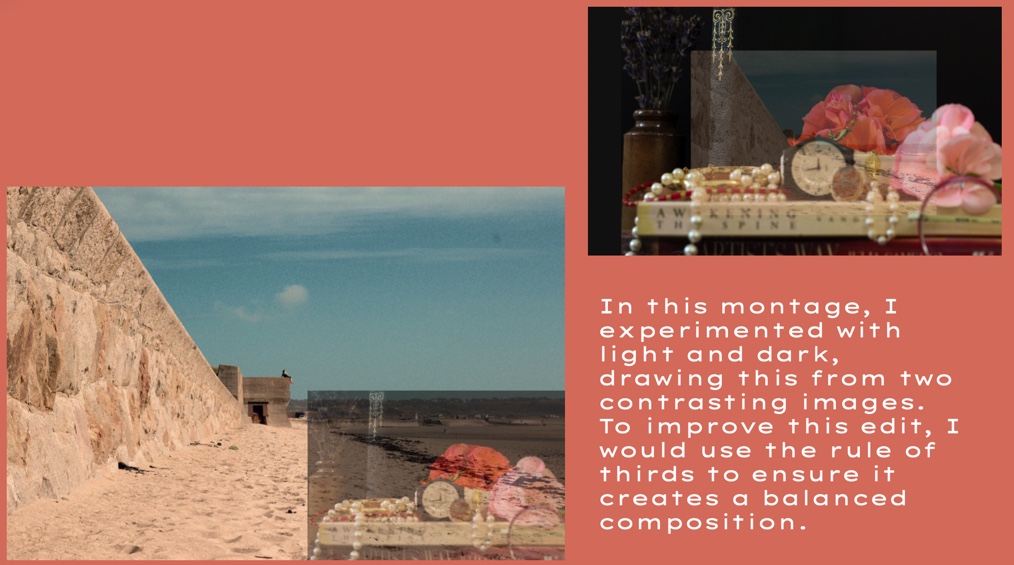

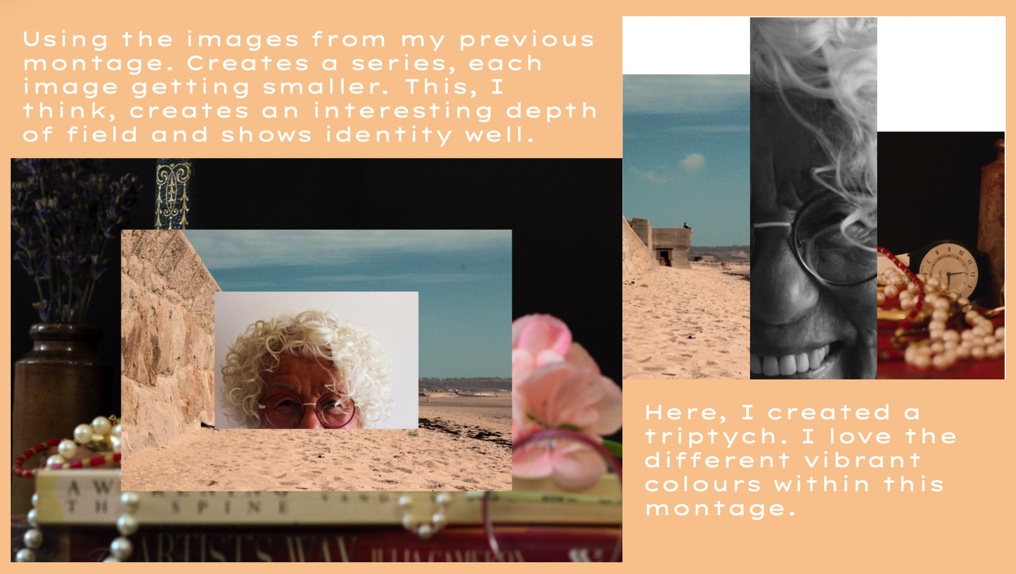

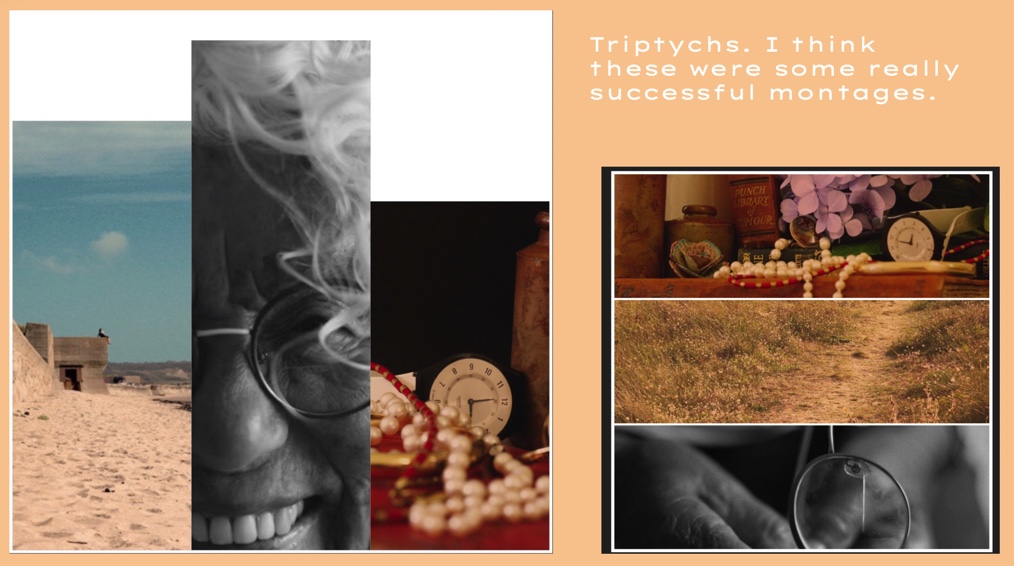

This is my second part of the highlights of my summer task: Montages and best images.