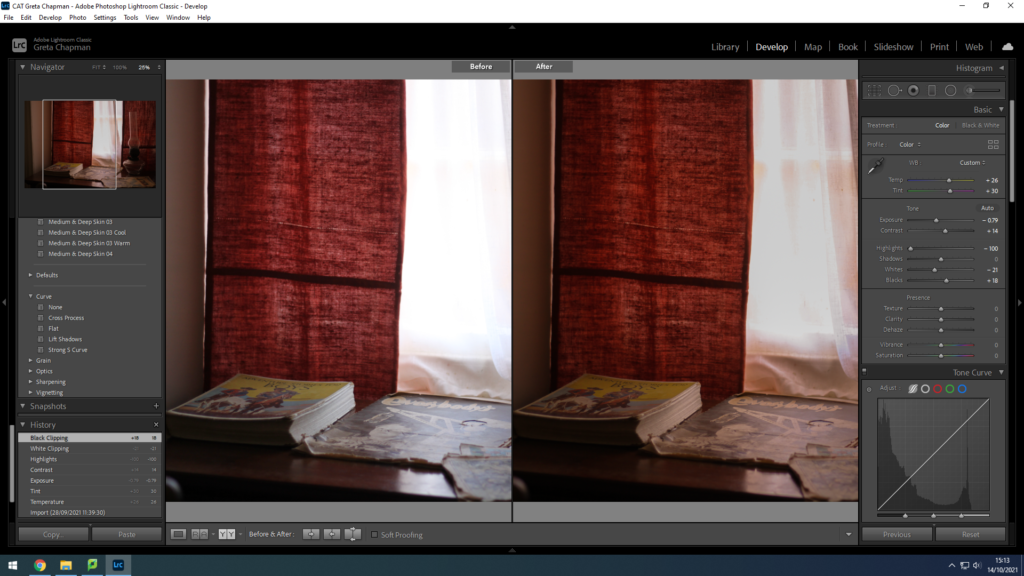

objects

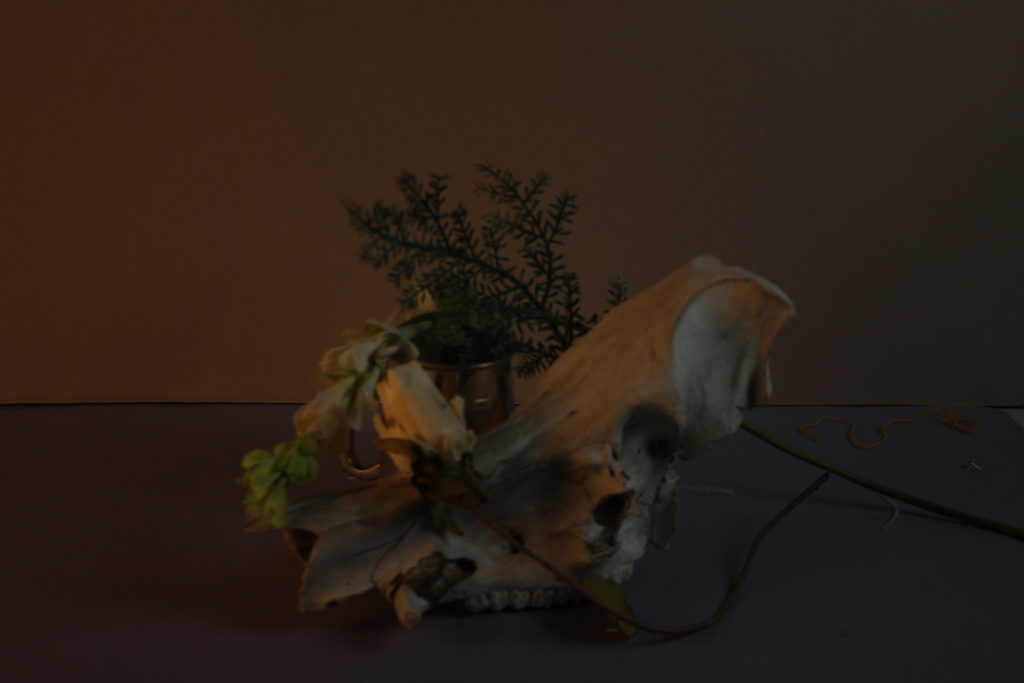

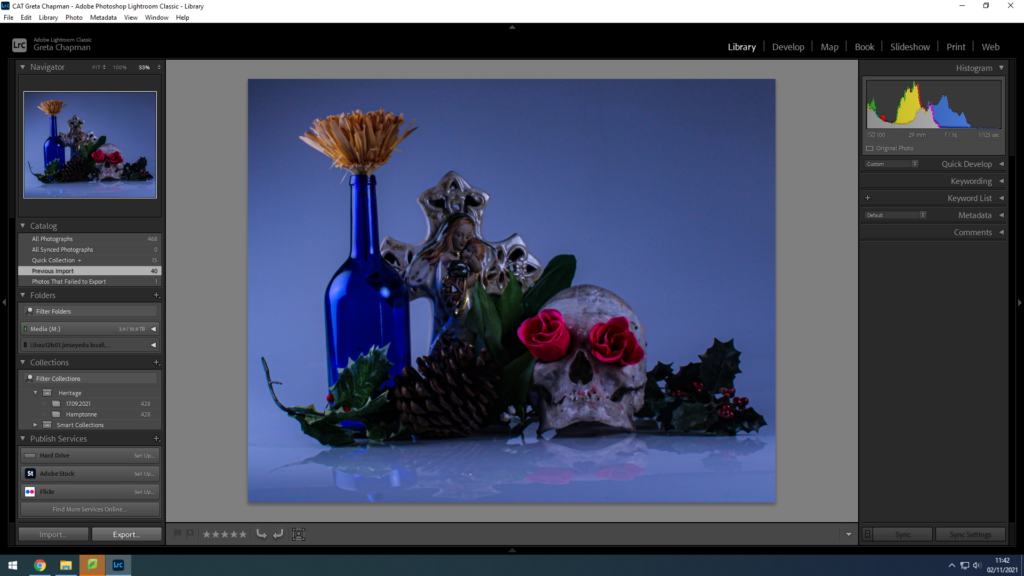

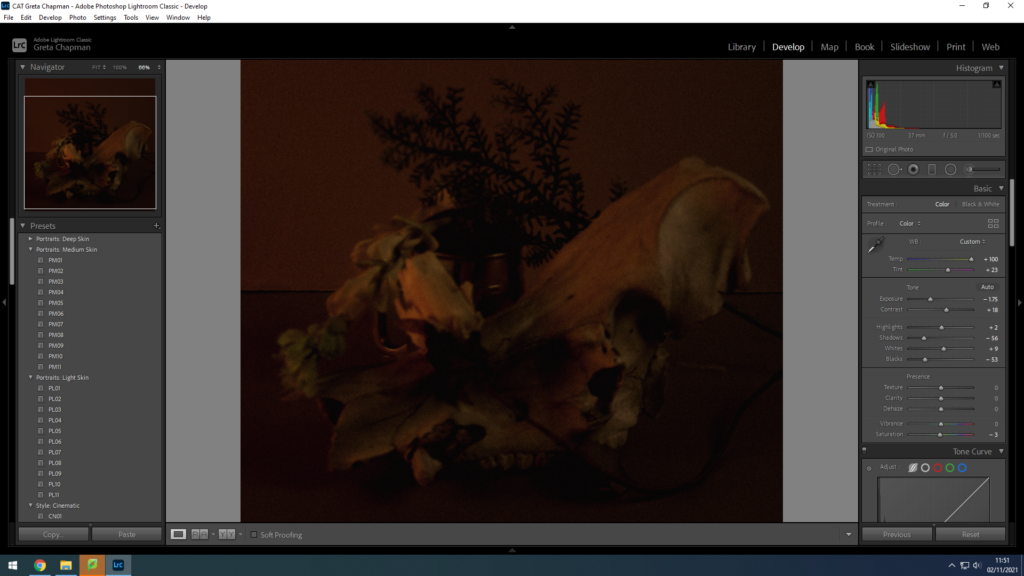

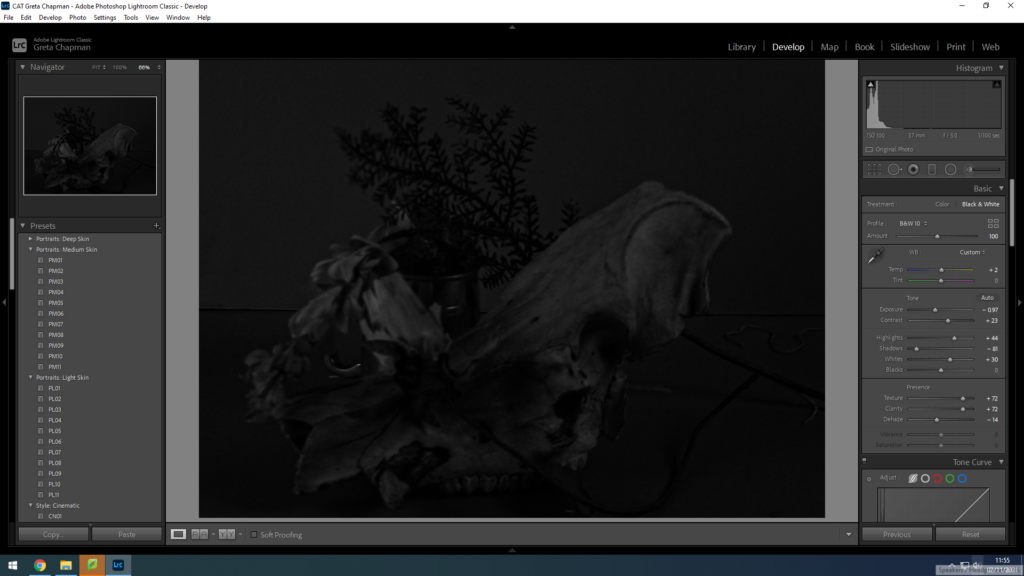

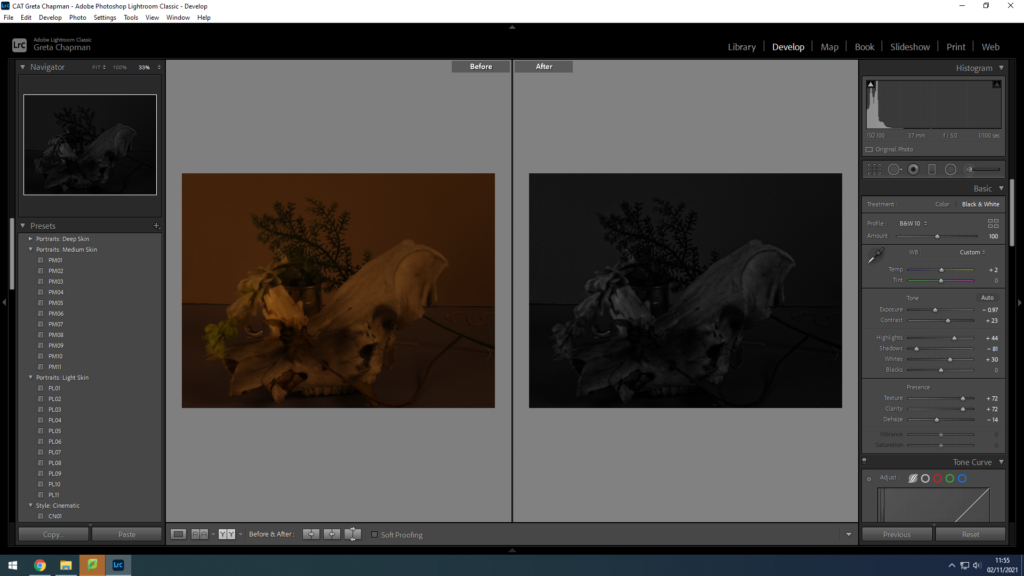

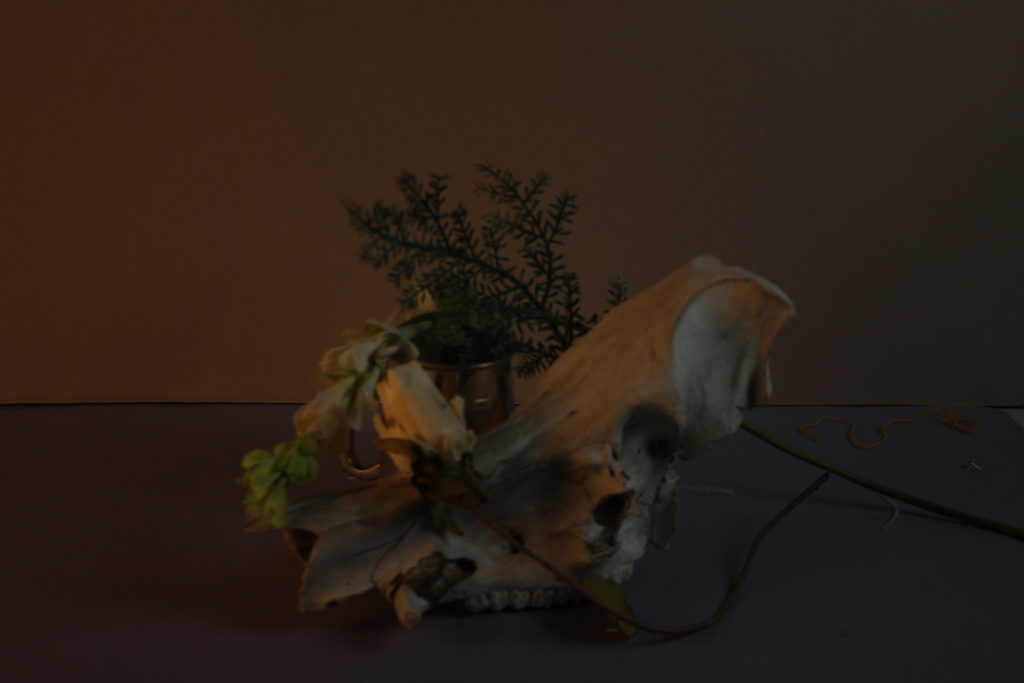

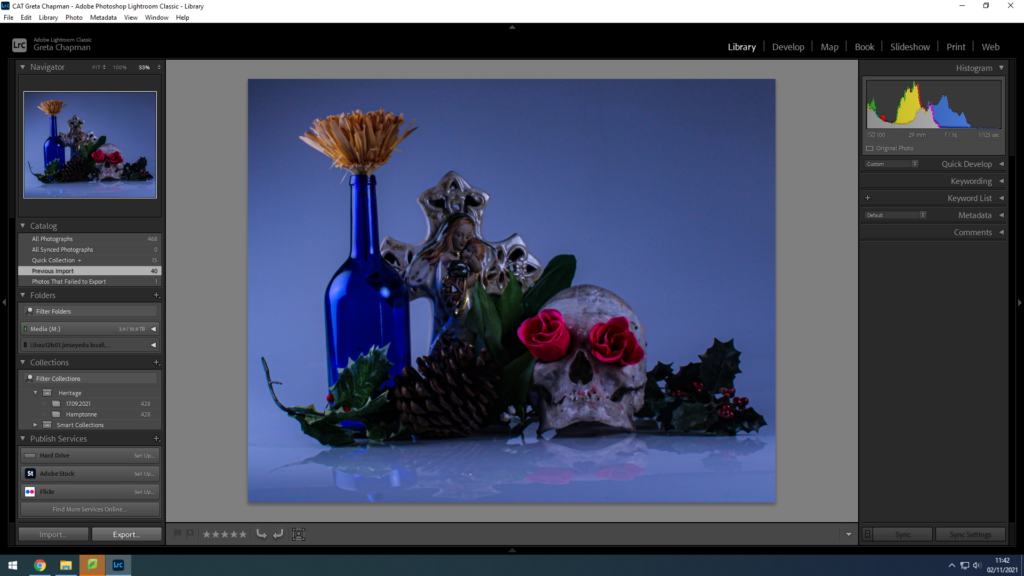

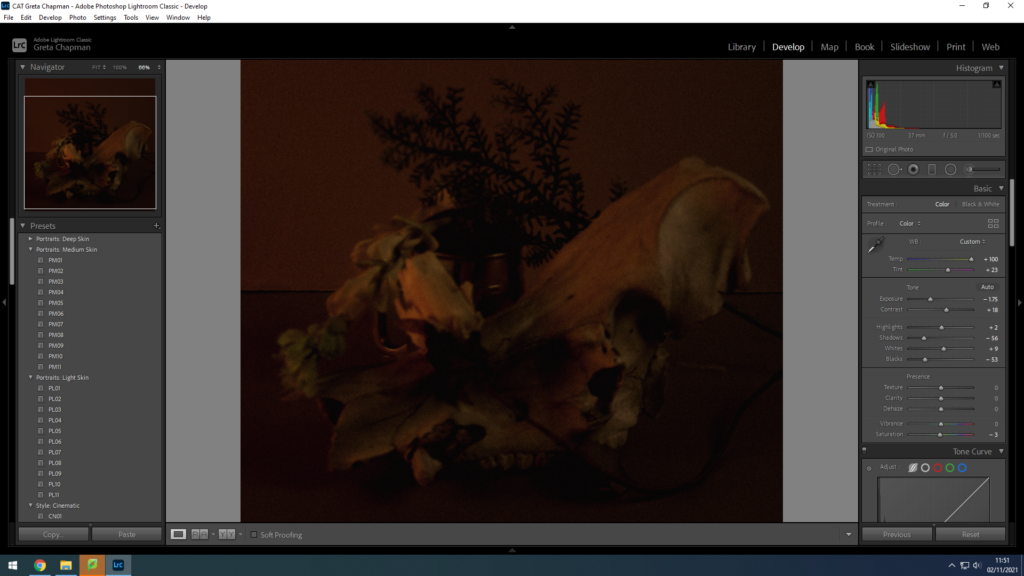

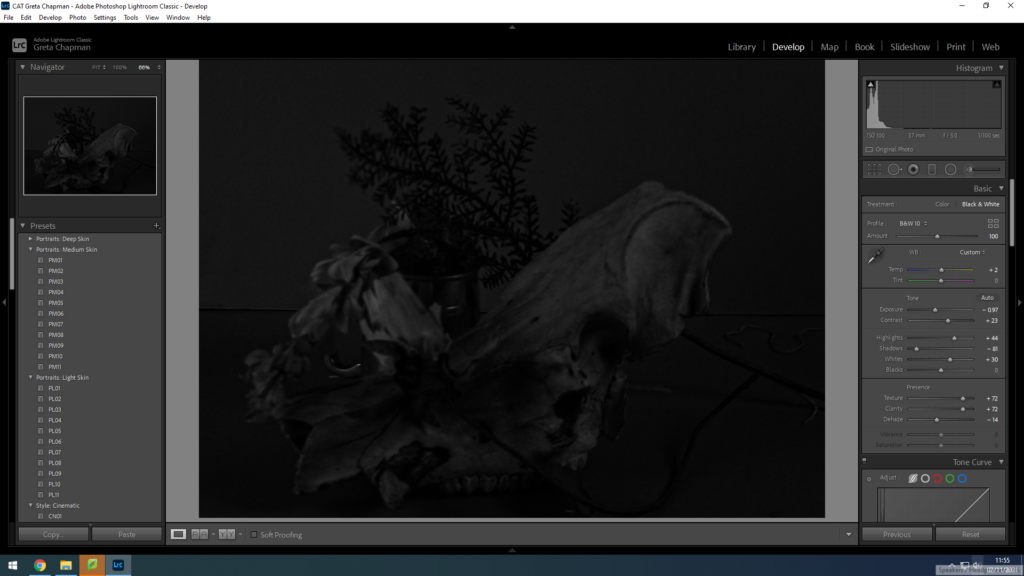

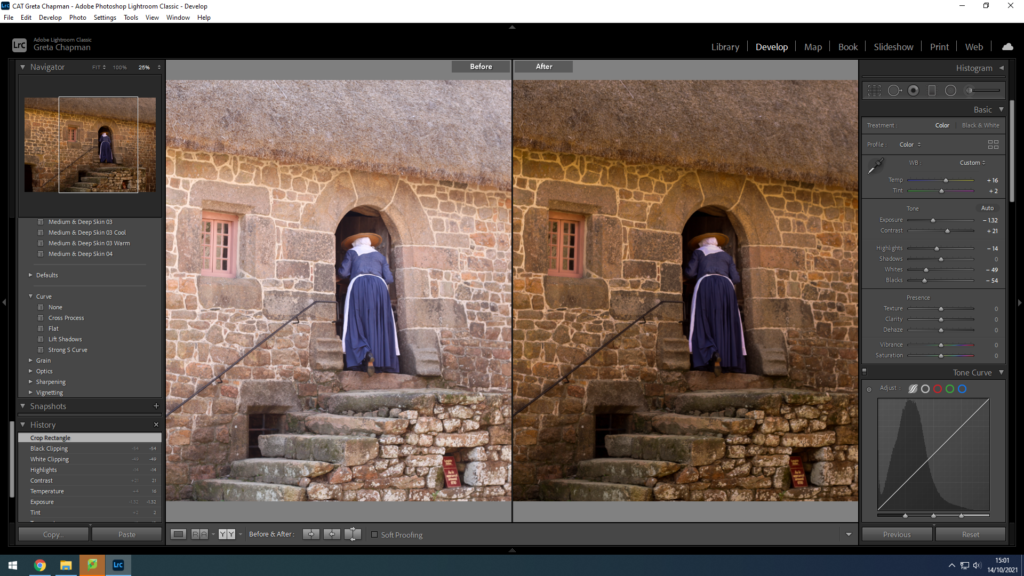

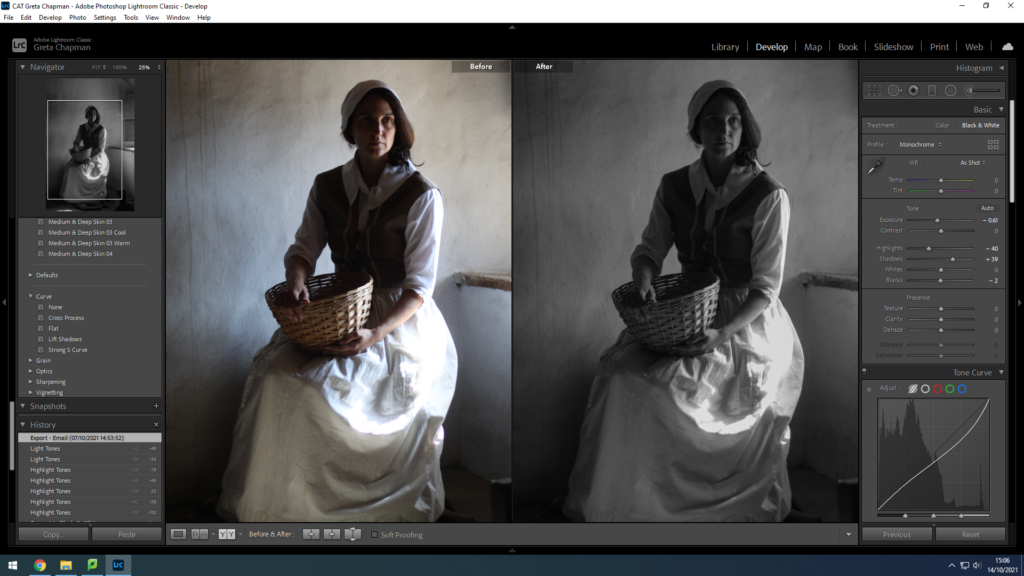

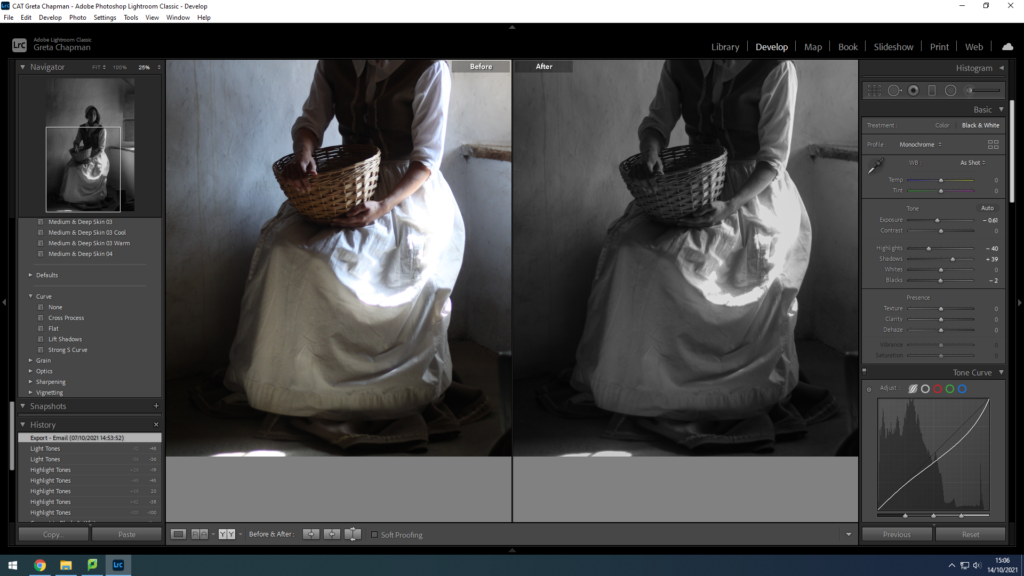

Before editing:

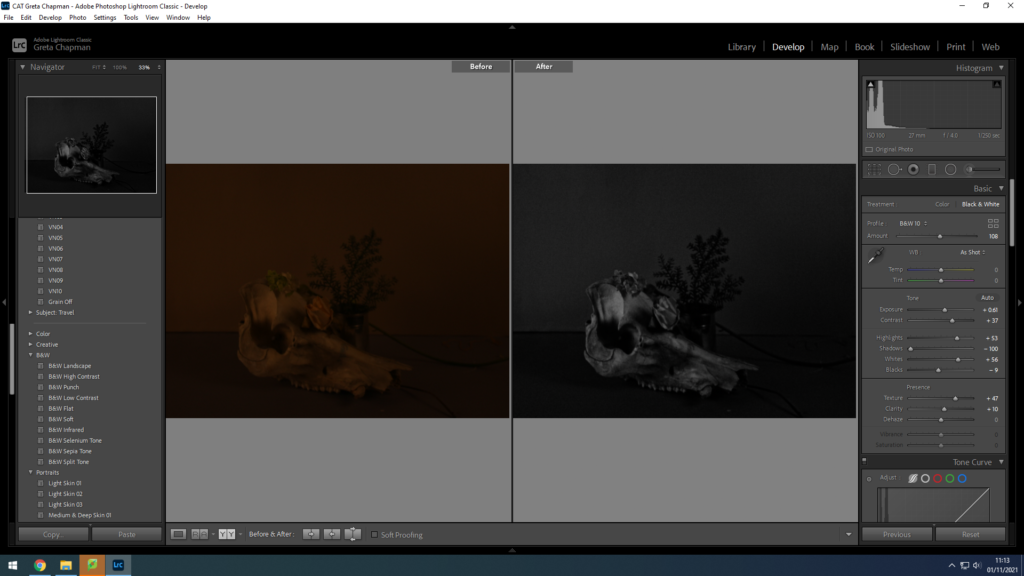

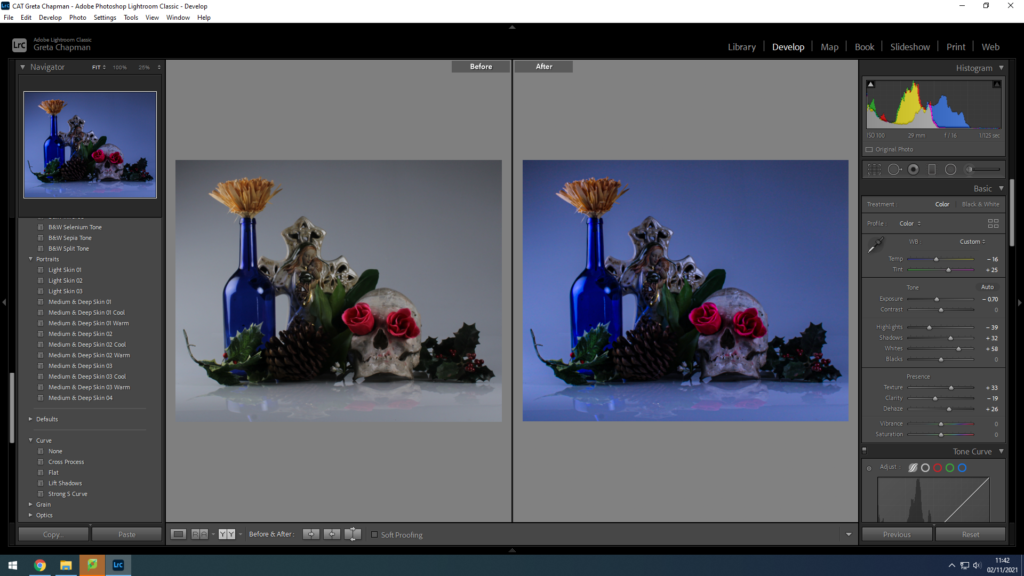

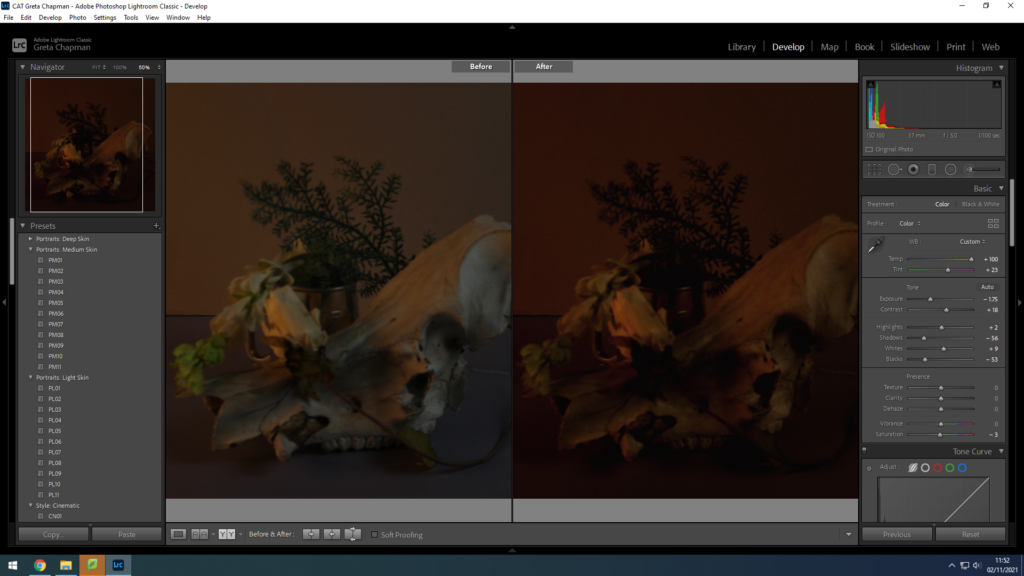

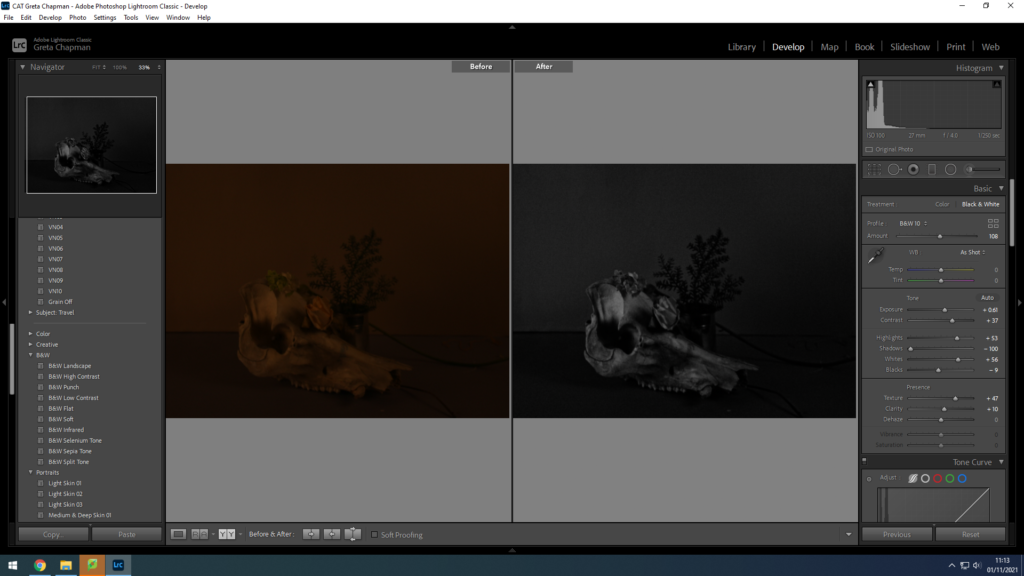

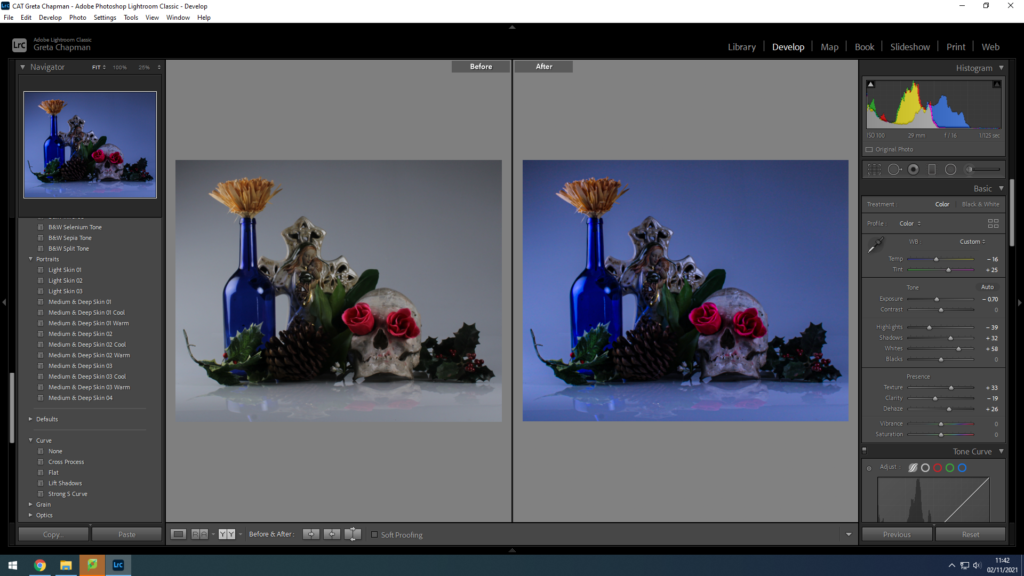

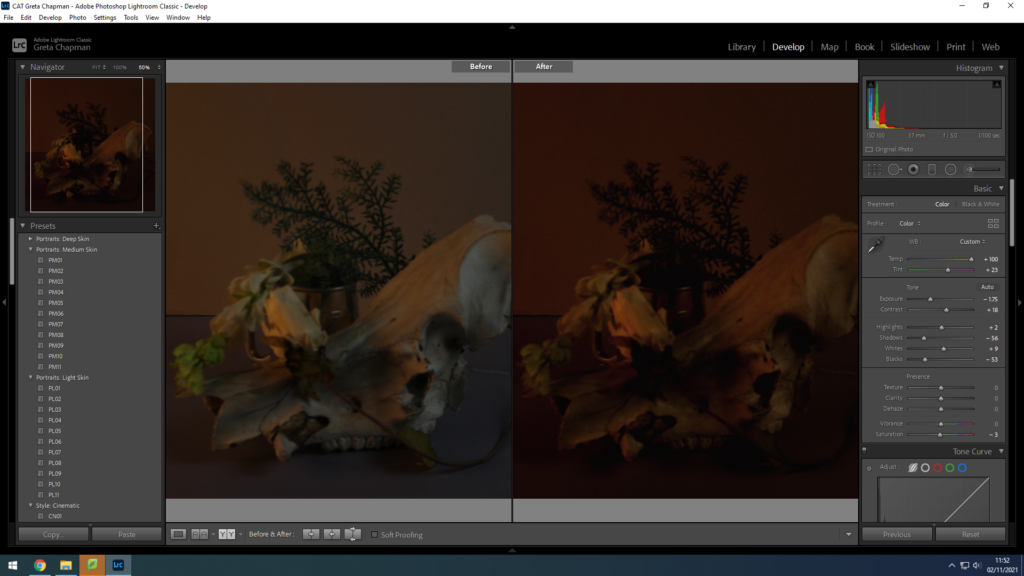

Editing:

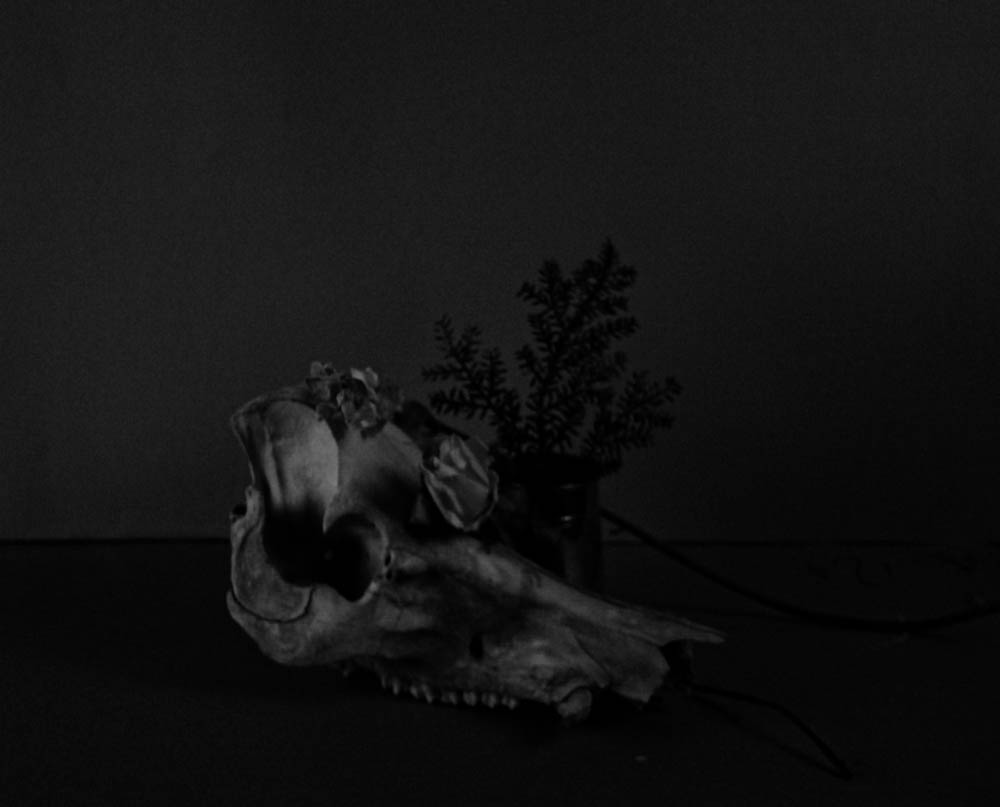

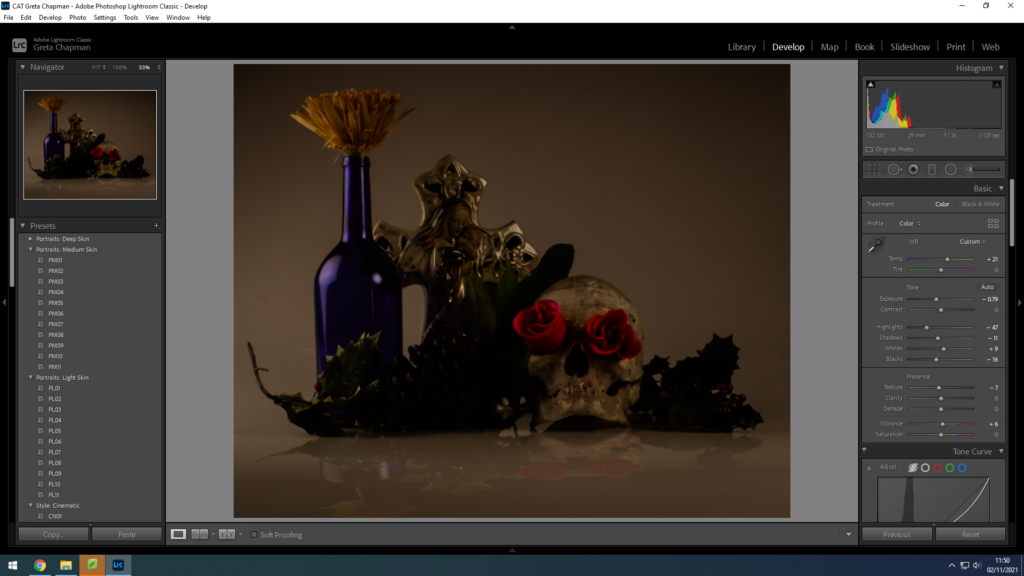

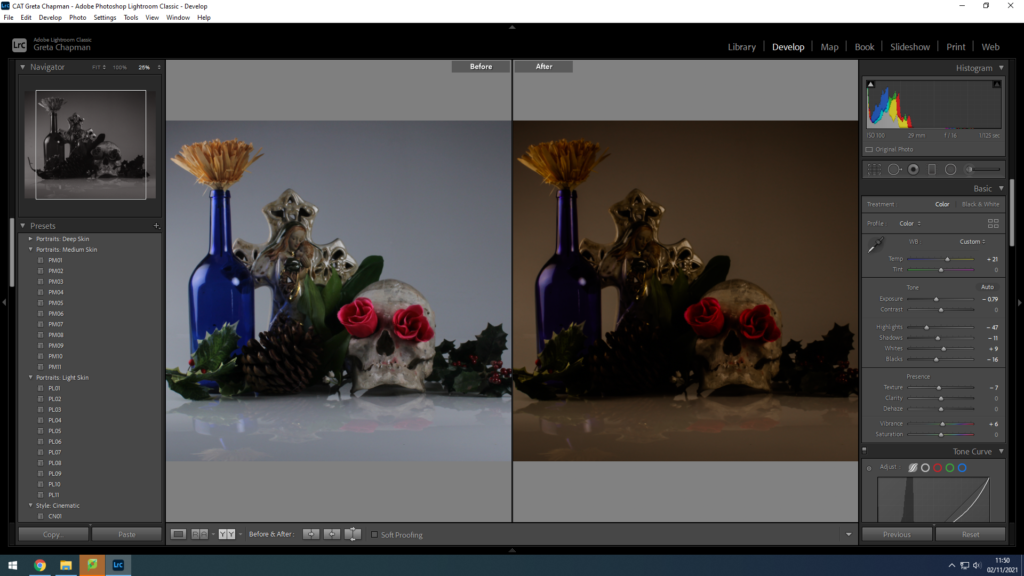

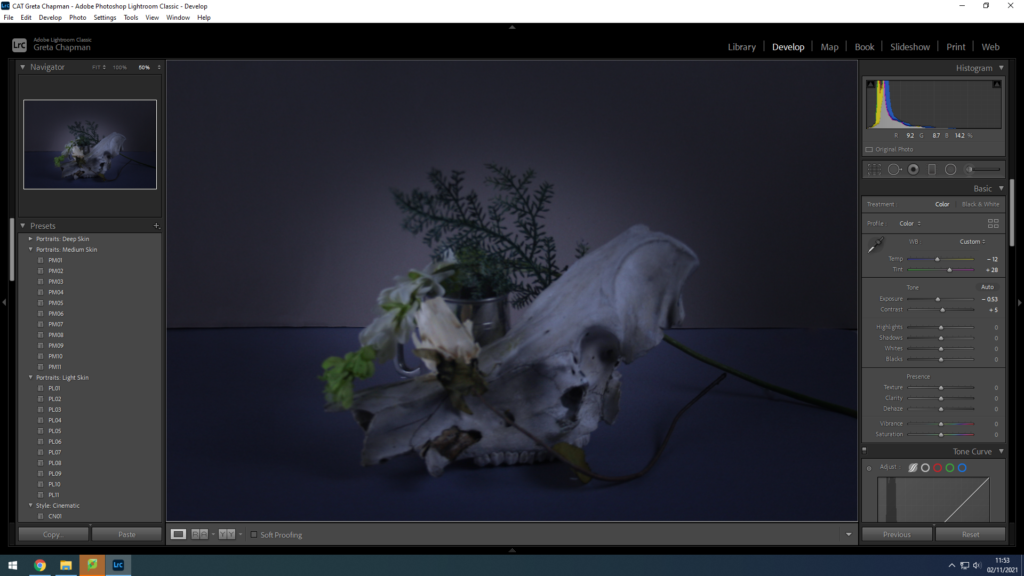

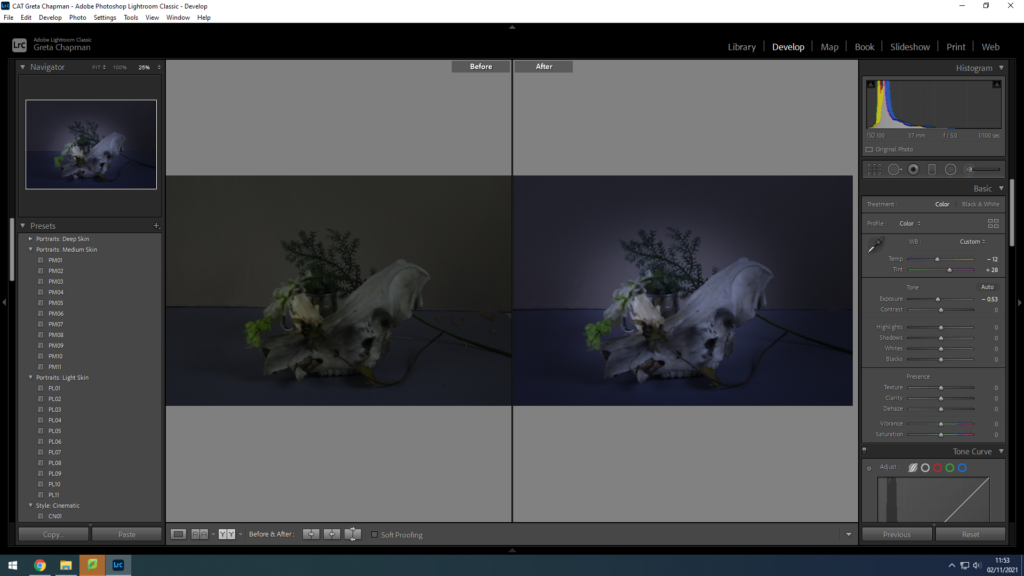

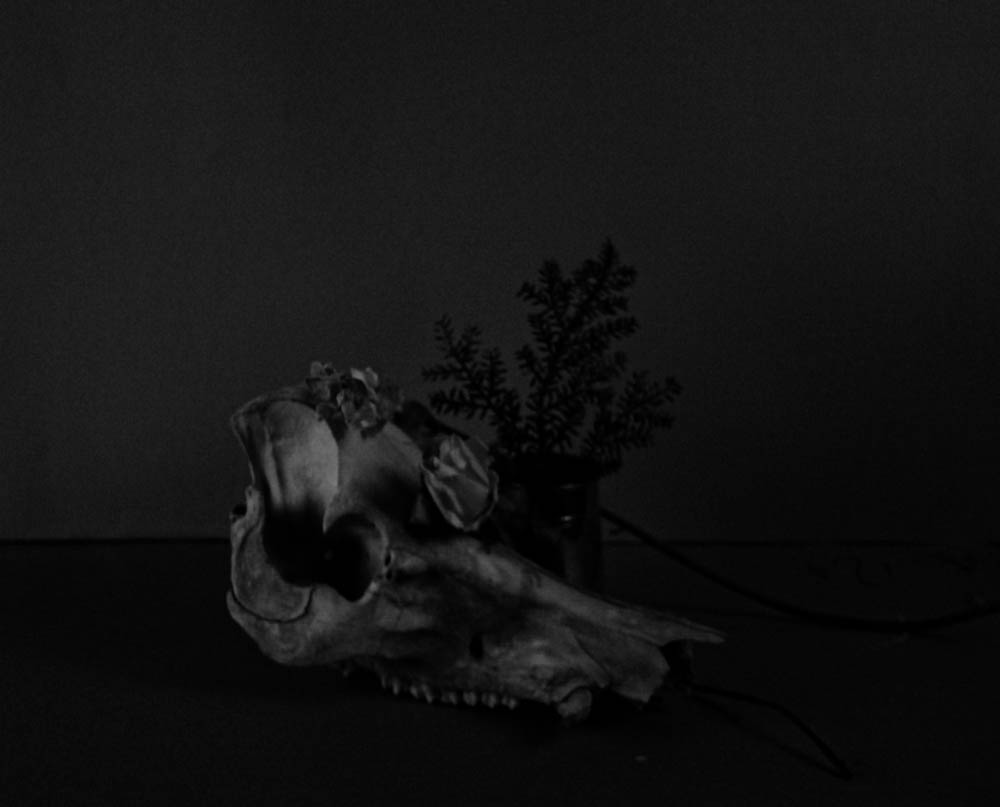

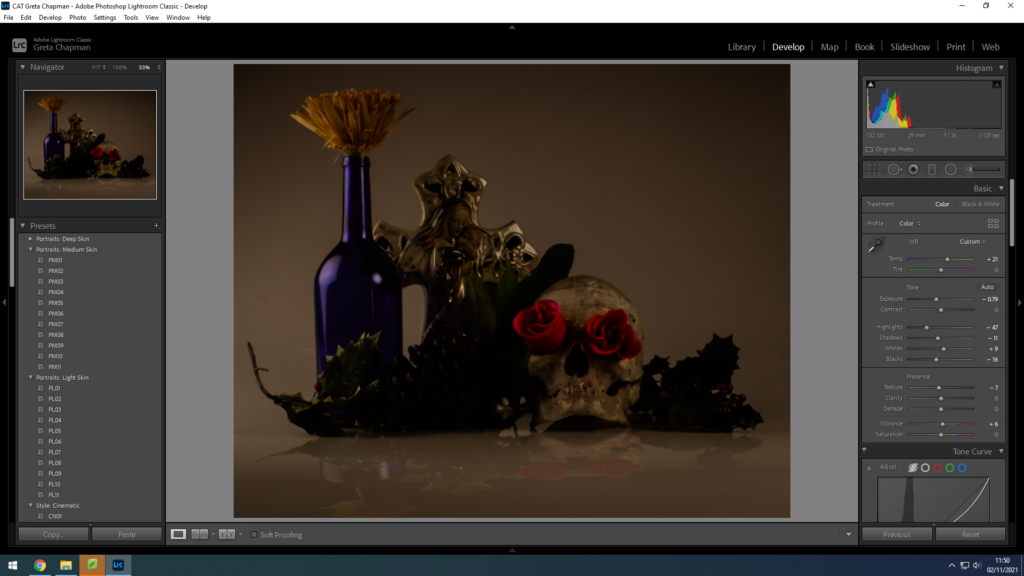

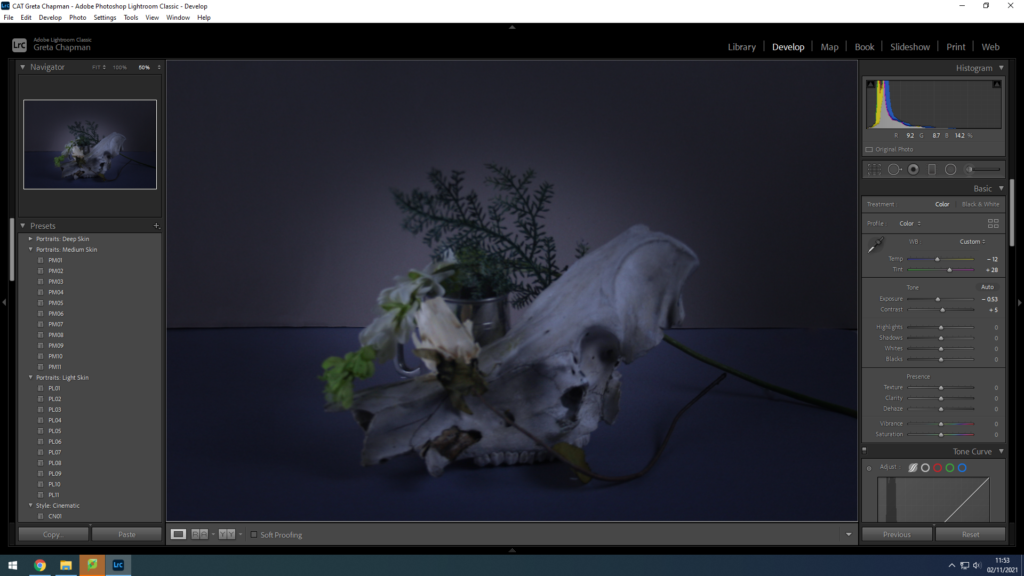

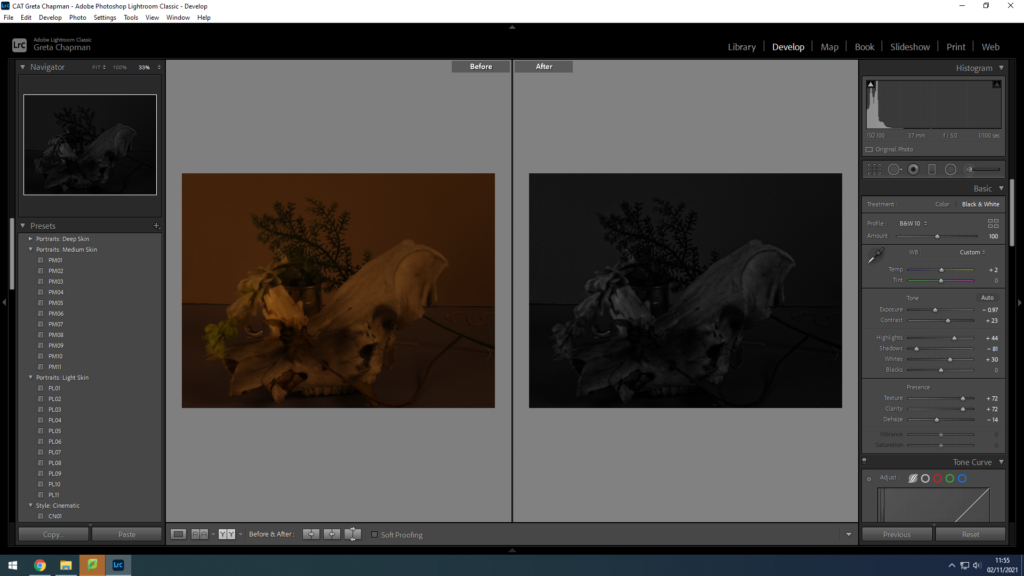

Final outcome:

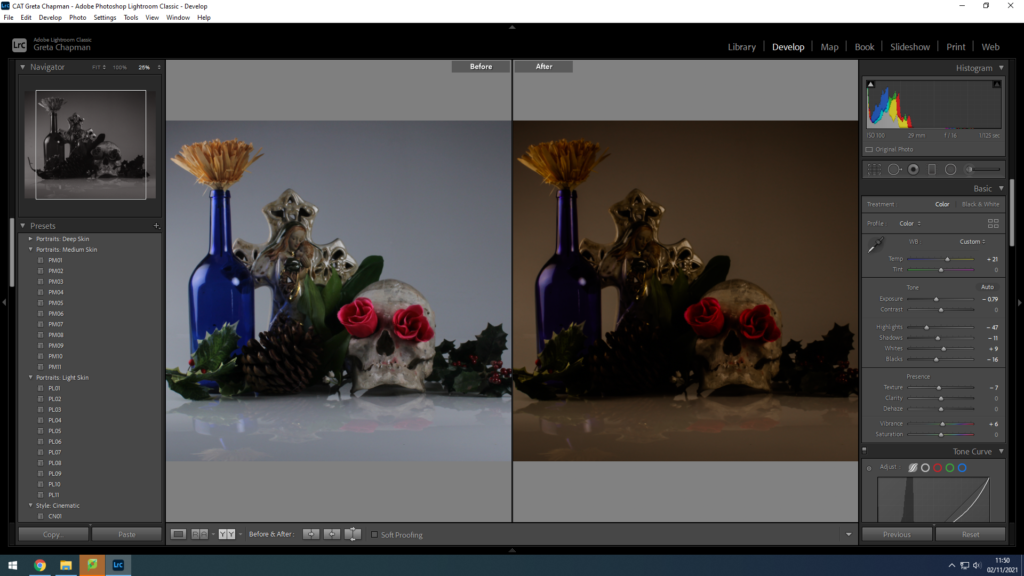

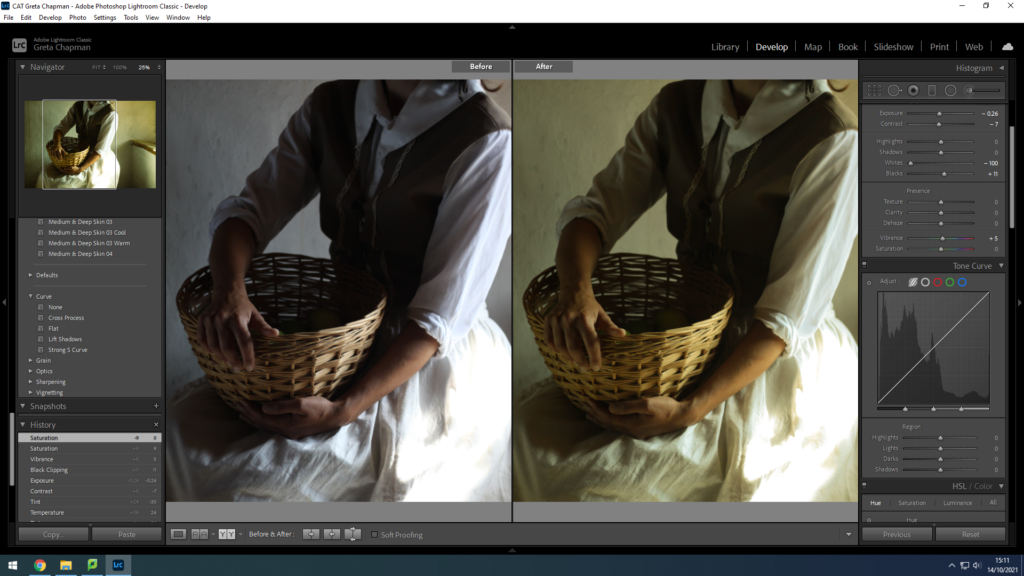

Final outcome:

Final outcome:

Final outcome

Final outcome:

Final outcome:

Final outcome:

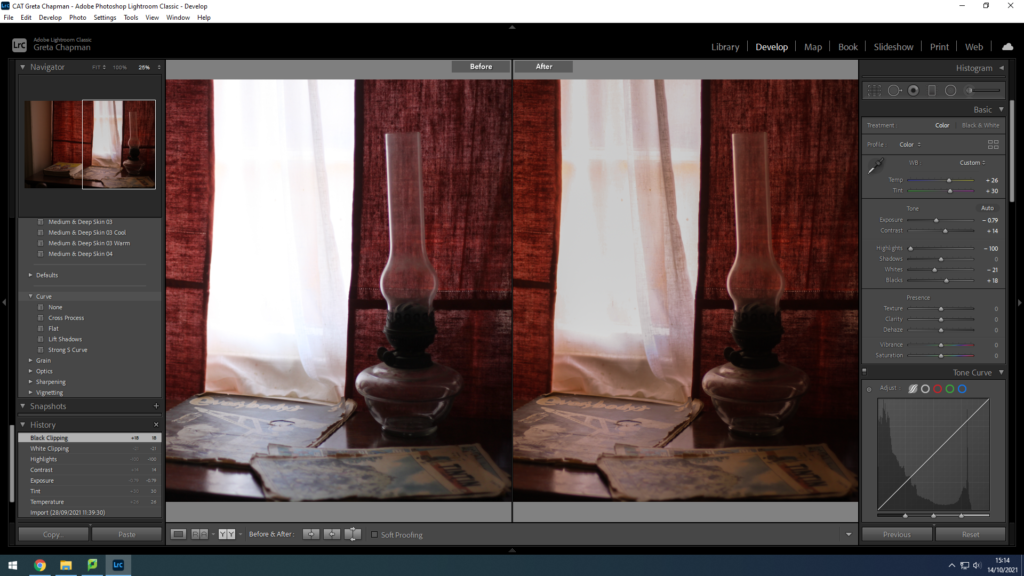

objects

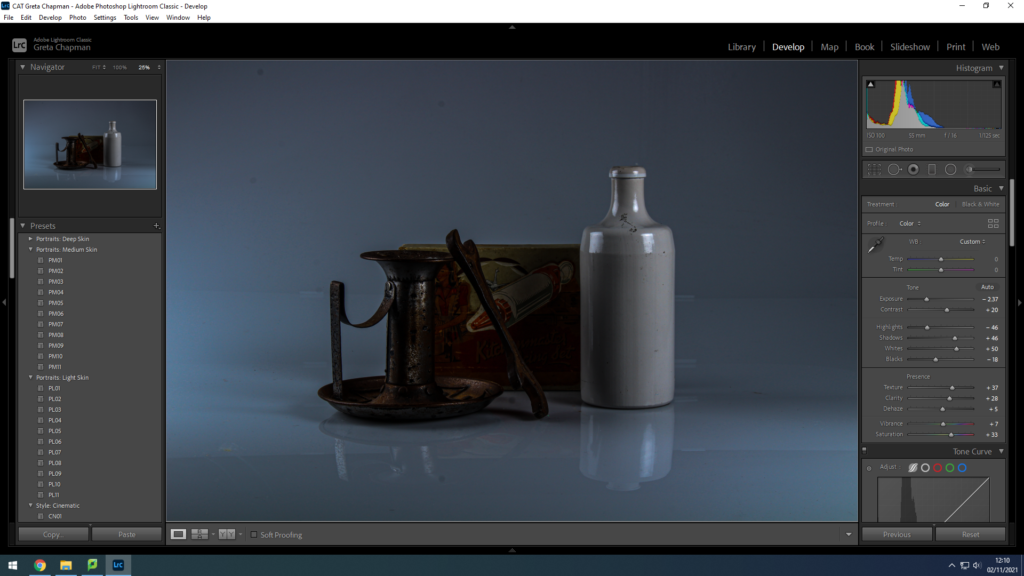

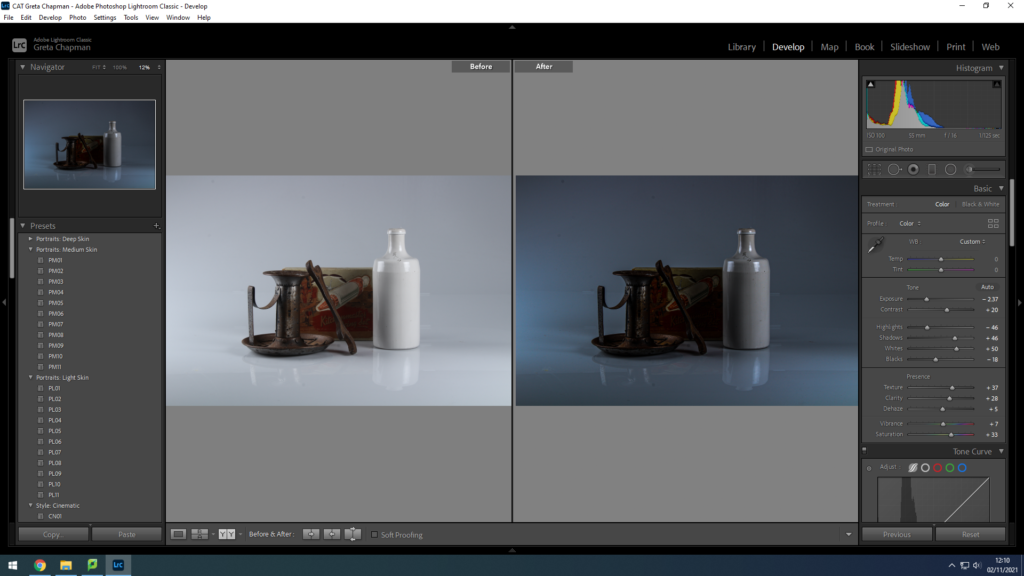

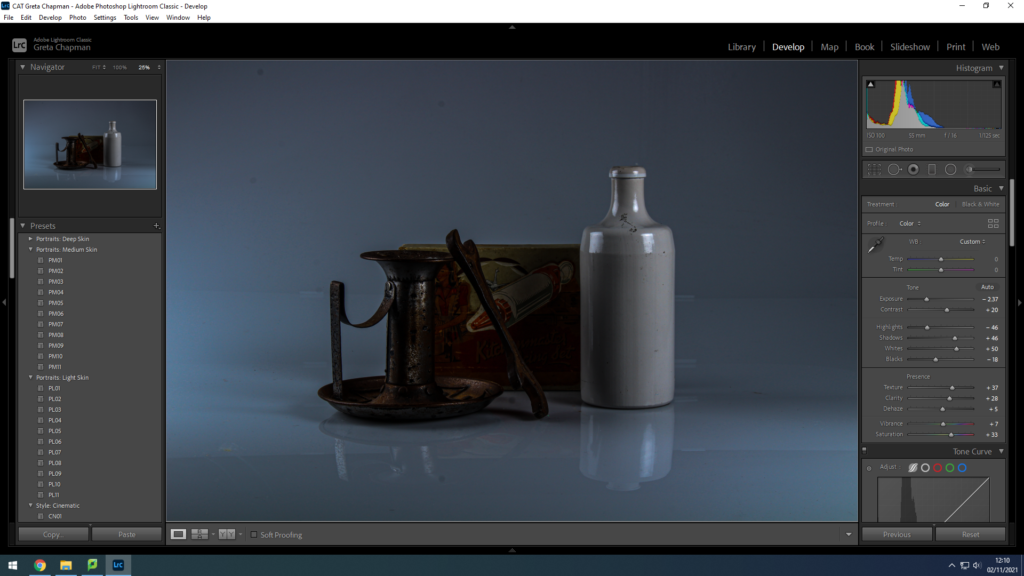

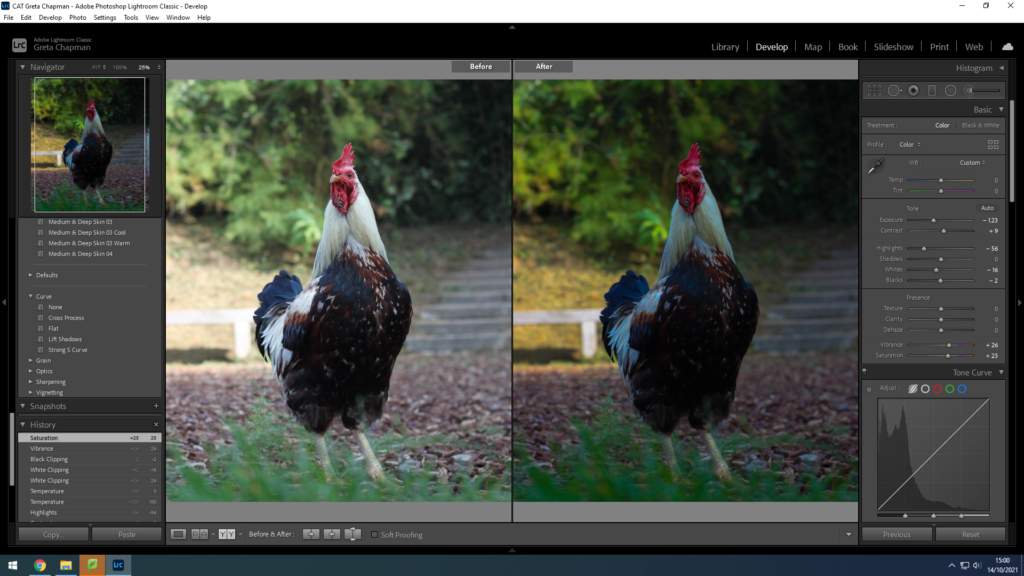

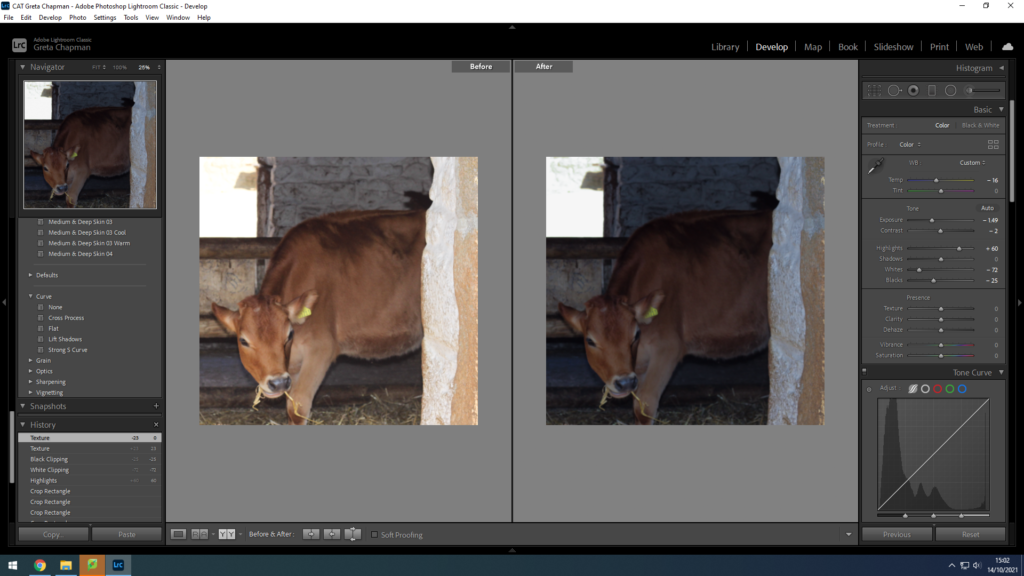

Before editing:

Editing:

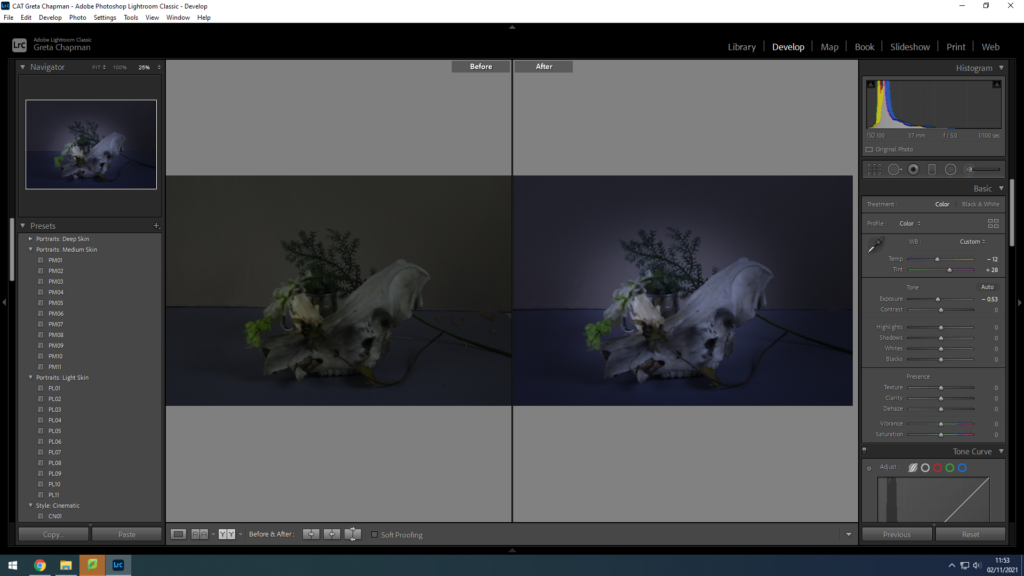

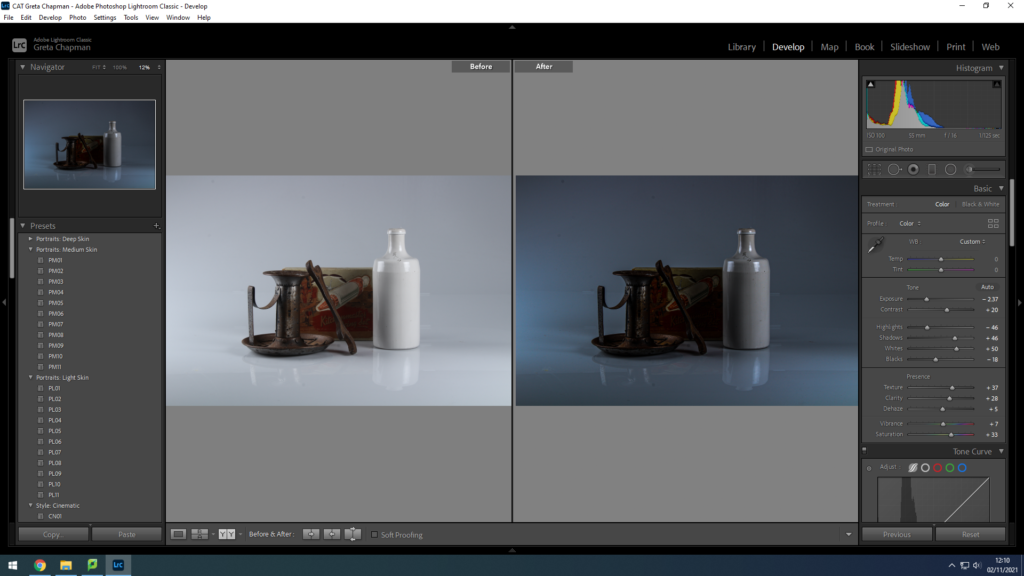

Final outcome:

Final outcome:

Final outcome:

Final outcome

Final outcome:

Final outcome:

Final outcome:

HAMPTONNE OBJECTS

He was born in St. Louis, Missouri to Jessie (née Crane) and Walker Evans. His father was an advertising director. Walker was raised in an affluent environment; he spent his youth in Toledo, Ohio; Chicago; and New York City. He attended the Loomis Institute and Mercersburg Academy, then graduated from Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts in 1922. He studied French literature for a year at Williams College, spending much of his time in the school’s library, before dropping out. He returned to New York and worked as a night attendant in the map room of the Public Library. After spending a year in Paris in 1926, he returned to the United States to join a literary and art crowd in New York City. John Cheever, Hart Crane, and Lincoln Kirstein were among his friends. He was a clerk for a stockbroker firm on Wall Street from 1927 to 1929.

Evans took up photography in 1928 around the time he was living in Ossining, New York. His influences included Eugène Atget and August Sander. In 1930, he published three photographs (Brooklyn Bridge) in the poetry book The Bridge by Hart Crane. In 1931, he made a photo series of Victorian houses in the Boston vicinity sponsored by Lincoln Kirstein.

In May and June 1933, Evans took photographs in Cuba on assignment for Lippincott, the publisher of Carleton Beals’ The Crime of Cuba (1933), a “strident account” of the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado. There, Evans drank nightly with Ernest Hemingway, who lent him money to extend his two-week stay an additional week. His photographs documented street life, the presence of police, beggars and dockworkers in rags, and other waterfront scenes. He also helped Hemingway acquire photos from newspaper archives that documented some of the political violence Hemingway described in To Have and Have Not (1937). Fearing that his photographs might be deemed critical of the government and confiscated by Cuban authorities, he left 46 prints with Hemingway. He had no difficulties when returning to the United States, and 31 of his photos appeared in Beals’ book. The cache of prints left with Hemingway was discovered in Havana in 2002 and exhibited at an exhibition in Key West.

The Depression years of 1935–36 were ones of remarkable productivity and accomplishment for Evans. In 1935, Evans spent two months on a fixed-term photographic campaign in West Virginia and Pennsylvania. In June 1935, he accepted a job from the U.S. Department of the Interior to photograph a government-built resettlement community of unemployed coal miners in West Virginia. He quickly parlayed this temporary employment into a full-time position as an “information specialist” in the Resettlement Administration (later Farm Security Administration), a New Deal agency in the Department of Agriculture. From October 1935 on, he continued to do photographic work for the RA and later the Farm Security Administration, primarily in the Southern United States.

In the summer of 1936, while on leave from the FSA, writer James Agee and he were sent by Fortune on assignment to Hale County, Alabama for a story the magazine subsequently opted not to run. In 1941, Evans’s photographs and Agee’s text detailing the duo’s stay with three White tenant families in southern Alabama during the Great Depression were published as the ground-breaking book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Its detailed account of three farming families paints a deeply moving portrait of rural poverty. Critic Janet Malcolm notes that a contradiction existed between a kind of anguished dissonance in Agee’s prose and the quiet, magisterial beauty of Evans’s photographs of sharecroppers.

Walker Evans gained his eye for knowing what a great photograph was through the visual education of his painter friends. He undoubtedly became influenced by the great works of artists that his friends would probably talk about, share, and aspire towards.

Evans died at his apartment in New Haven, Connecticut in 1975. The last person Evans talked to was Hank O’Neal. In reference to the newly created A Vision Shared project, O’Neal recounts, “The picture on the back of the book, of him taking a picture – he actually called me up and told me he had found it”. “And then the next morning I got up and I had a phone call from Leslie Katz, who ran the Eakins Press. And Leslie said: ‘Isn’t it terrible about Walker Evans?’ And I said: ‘What are you talking about?’ He said: ‘He died last night.’ I said: ‘Cut it out. I talked to him last night twice’ So an hour and a half after we had our conversation, he died. He had a stroke and died.”

In 1994, the estate of Walker Evans handed over its holdings to New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is the sole copyright holder for all works of art in all media by Walker Evans. The only exception is a group of about 1,000 negatives in collection of the Library of Congress, which were produced for the Resettlement Administration and Farm Security Administration; these works are in the public domain.

In 2000, Evans was inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame.

some of his work:

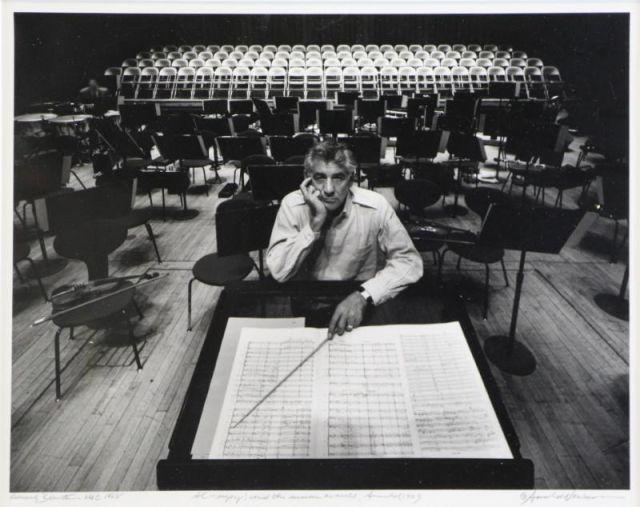

An environmental portrait is a portrait executed in the subject’s usual environment, such as in their home or workplace, and typically illuminates the subject’s life and surroundings. The term is most frequently used of a genre of photography.

By photographing a person in their natural surroundings, it is thought that you will be able to better illuminate their character, and therefore portray the essence of their personality, rather than merely a likeness of their physical features. It is also thought that by photographing a person in their natural surroundings, the subject will be more at ease, and so be more conducive to expressing themselves, as opposed to in a studio, which can be a rather intimidating and artificial experience.

The surroundings or background is a key element in environmental portraiture, and is used to convey further information about the person being photographed.

Where it is common in studio portraiture and even in location candid photography to shoot using a shallow depth of field, thereby throwing the background out of focus, the background in environmental portraiture is an integral part of the image. Indeed, small apertures and great depth of field are commonly used in this type of photography.

Mary Ellen Mark: (1940-2015)

Mary Ellen Mark (March 20, 1940 – May 25, 2015) was an American photographer known for her photojournalism, documentary photography, portraiture, and advertising photography. She photographed people who were “away from mainstream society and toward its more interesting, often troubled fringes”.

Mark had 18 collections of her work published, most notably Streetwise and Ward 81. Her work was exhibited at galleries and museums worldwide and widely published in Life, Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, New York Times, and Vanity Fair. She was a member of Magnum Photos between 1977 and 1981. She received numerous accolades, including three Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Awards, three fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the 2014 Lifetime Achievement in Photography Award from the George Eastman House and the Outstanding Contribution Photography Award from the World Photography Organisation.

Mark was born and raised in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania and began photographing with a Box Brownie camera at age nine. She attended Cheltenham High School, where she was head cheerleader and exhibited a knack for painting and drawing. She received a Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting and art history from the University of Pennsylvania in 1962. After graduating, she worked briefly in the Philadelphia city planning department, then returned for a master’s degree in photojournalism at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, which she received in 1964. The following year, Mark received a Fulbright Scholarship to photograph in Turkey for a year, from which she produced her first book, Passport (1974). While there, she travelled to photograph England, Germany, Greece, Italy, and Spain.

In 1966 or 1967, she moved to New York City, where over the next several years she photographed demonstrations in opposition to the Vietnam War, the women’s liberation movement, transvestite culture, and Times Square, developing a sensibility, according to one writer, “away from mainstream society and toward its more interesting, often troubled fringes”. Her photography addressed social issues such as homelessness, loneliness, drug addiction, and prostitution. Children are a reoccurring subject throughout much of Mark’s work. She described her approach to her subjects: “I’ve always felt that children and teenagers are not “children,” they’re small people. I look at them as little people and I either like them or I don’t like them. I also have an obsession with mental illness. And strange people who are outside the borders of society.” Mark also said “I’d rather pull up things from another culture that are universal, that we can all relate to…There are prostitutes all over the world. I try to show their way of life.” and that “I feel an affinity for people who haven’t had the best breaks in society. What I want to do more than anything is acknowledge their existence”. Mark was well known for establishing strong relationships with her subjects. For Ward 81 (1979), she lived for six weeks with the patients in the women’s security ward of Oregon State Hospital, and for Falkland Road (1981), she spent three months befriending the prostitutes who worked on a single long street in Bombay. Her project “Streets of the Lost” with writer Cheryl McCall, for Life, produced her book Streetwise (1988) and was developed into the documentary film Streetwise, directed by her husband Martin Bell and with a soundtrack by Tom Waits.

Mary Ellen Mark (1940- 2015) is one of the leading documentary photographers of the past half-century, and has achieved worldwide visibility through her many exhibitions, books, photo essays and portraits.

Mark traveled extensively since her first trip to Turkey on a Fulbright Scholarship in 1965. Her pictures of diverse people and cultures are groundbreaking images in the documentary field. Her essays on runaway children in Seattle, circuses and brothels in India, Catholic and Protestant women in Northern Ireland and patients in the maximum-security ward of Oregon State Mental Hospital demonstrate original and insightful ways of examining each theme. Her photographs are compassionate and factual.

Mark’s photographs have appeared in The Times Magazine, The New Yorker, Rolling Stone and Vogue. Among her many books are Ward 81 (Simon & Schuster, 1979); Falkland Road (Knopf, 1981); Mary Ellen Mark: 25 Years (Bullfinch, 1991); Mary Ellen Mark: American Odyssey (Aperture, 1999); and, most recently, Mary Ellen Mark: The Book of Everything (Steidl, 2020). Mark earned three fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Photographer of the Year Award from the Friends of Photography, the World Press Award for Outstanding Body of Work Throughout the Years, the Victor Hasselblad Cover Award and two Robert F. Kennedy Awards. She was the associate producer of the film American Heart (1992), directed by Martin Bell.

some of her work:

Photography is the art, application, and practice of creating durable images by recording light, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film. It is employed in many fields of science, manufacturing (e.g., photolithography), and business, as well as its more direct uses for art, film and video production, recreational purposes, hobby, and mass communication.

Typically, a lens is used to focus the light reflected or emitted from objects into a real image on the light-sensitive surface inside a camera during a timed exposure. With an electronic image sensor, this produces an electrical charge at each pixel, which is electronically processed and stored in a digital image file for subsequent display or processing. The result with photographic emulsion is an invisible latent image, which is later chemically “developed” into a visible image, either negative or positive depending on the purpose of the photographic material and the method of processing. A negative image on film is traditionally used to photographically create a positive image on a paper base, known as a print, either by using an enlarger or by contact printing.

Abstract photography –

Abstract photography, sometimes called non-objective, experimental or conceptual photography, is a means of depicting a visual image that does not have an immediate association with the object world and that has been created through the use of photographic equipment, processes or materials. An abstract photograph may isolate a fragment of a natural scene in order to remove its inherent context from the viewer, it may be purposely staged to create a seemingly unreal appearance from real objects, or it may involve the use of colour, light, shadow, texture, shape and/or form to convey a feeling, sensation or impression. The image may be produced using traditional photographic equipment like a camera, darkroom or computer, or it may be created without using a camera by directly manipulating film, paper or other photographic media, including digital presentations.

Many photographers, critics, art historians and others have written or spoken about abstract photography without attempting to formalize a specific meaning. Alvin Langdon Coburn in 1916 proposed that an exhibition be organized with the title “Abstract Photography”, for which the entry form would clearly state that “no work will be admitted in which the interest of the subject matter is greater than the appreciation of the extraordinary.” The proposed exhibition did not happen, yet Coburn later created some distinctly abstract photographs.

Landscape–

Landscape photography shows spaces within the world, sometimes vast and unending, but other times microscopic. Landscape photographs typically capture the presence of nature but can also focus on man-made features or disturbances of landscapes. Landscape photography is done for a variety of reasons. Perhaps the most common is to recall a personal observation or experience while in the outdoors, especially when traveling. Others pursue it particularly as an outdoor lifestyle, to be involved with nature and the elements, some as an escape from the artificial world.

Many landscape photographs show little or no human activity and are created in the pursuit of a pure, unsullied depiction of nature, devoid of human influence—instead featuring subjects such as strongly defined landforms, weather, and ambient light. As with most forms of art, the definition of a landscape photograph is broad and may include rural or urban settings, industrial areas or nature photography.

portrait–

A portrait is a painting, photograph, sculpture, or other artistic representation of a person, in which the face and its expression is predominant. The intent is to display the likeness, personality, and even the mood of the person. For this reason, in photography a portrait is generally not a snapshot, but a composed image of a person in a still position. A portrait often shows a person looking directly at the painter or photographer, in order to most successfully engage the subject with the viewer.

Portraiture is a very old art form going back at least to ancient Egypt, where it flourished from about 5,000 years ago. Before the invention of photography, a painted, sculpted, or drawn portrait was the only way to record the appearance of someone. But portraits have always been more than just a record.

Portrait photography is about capturing the essence, personality, identity and attitude of a person utilizing backgrounds, lighting and posing. The goal is to capture a photo that appears both natural and prepared to allow the subject’s personality to show through.

In 1767, people protested about the export of grain from the Island. Anonymous threats were made against shipowners and a law was passed the following year to keep corn in Jersey. In August 1769 the States of Jersey repealed this law, claiming that crops in the Island were plentiful. There was suspicion that this was a ploy to raise the price of wheat, which would be beneficial to the rich, many of whom had ‘rentes’ owed to them on properties that were payable in wheat. As major landowners, the Lemprière family stood to profit hugely.

On Thursday 28 September 1769, a Court called the Assize d’Héritage was sitting, hearing cases relating to property disputes. The Lieutenant Bailiff, Charles Lemprière, sat as the Head of the Court. Meanwhile, a group of disgruntled individuals from Trinity, St Martin, St John, St Lawrence and St Saviour marched towards Town where their numbers were swelled by residents of St Helier. The group was met at the door of the Royal Court and was urged to disperse and send its demands in a more respectful manner. However, the crowd forced its way into the Court Room armed with clubs and sticks. Inside, they ordered that their demands be written down in the Court book. Although the King later commanded that the lines be removed from the book , a transcription survives that shows the crowd’s demands.

The demands of the Corn Riots protestors included:

• That the price of wheat be lowered and set at 20 sols per Cabot.

• That foreigners be ejected from the Island.

• That his Majesty’s tithes be reduced to 20 sols per vergée.

• That the value of the liard coin be set to 4 per sol.

• That there should be a limit on the sales tax.

• That seigneurs stop enjoying the practice of champart (the right to every twelfth sheaf of corn or bundle of flax).

• That seigneurs end the right of ‘Jouir des Successions’(the right to enjoy anyone’s estate for a year and a day if they die without heirs).

• That branchage fines could no longer be imposed.

• That Rectors could no longer charge tithes except on apples.

• That charges against Captain Nicholas Fiott be dropped and that he be allowed to return to the Island without an inquiry.

• That the Customs’ House officers be ejected.

The image is taken by Kevin Carter named “the vulture and the little girl” In the image is a starved boy, initially believed to be a girl who had collapsed due to starvation. In the background it appears to be a vulture eyeing him from nearby. It first appeared in The new York times. His photograph is a message to the people who are living in first world countries and showing the damage of world hunger.

The background looks very dry with not much life or plants growing and a hungry vulture keeping its eyes on the starving child. The appearance of the vulture is clearly stronger then the child. But in order of getting the ‘perfect shot’ Carter ignored his responsibility of helping the struggling girl but later chased the vulture off.