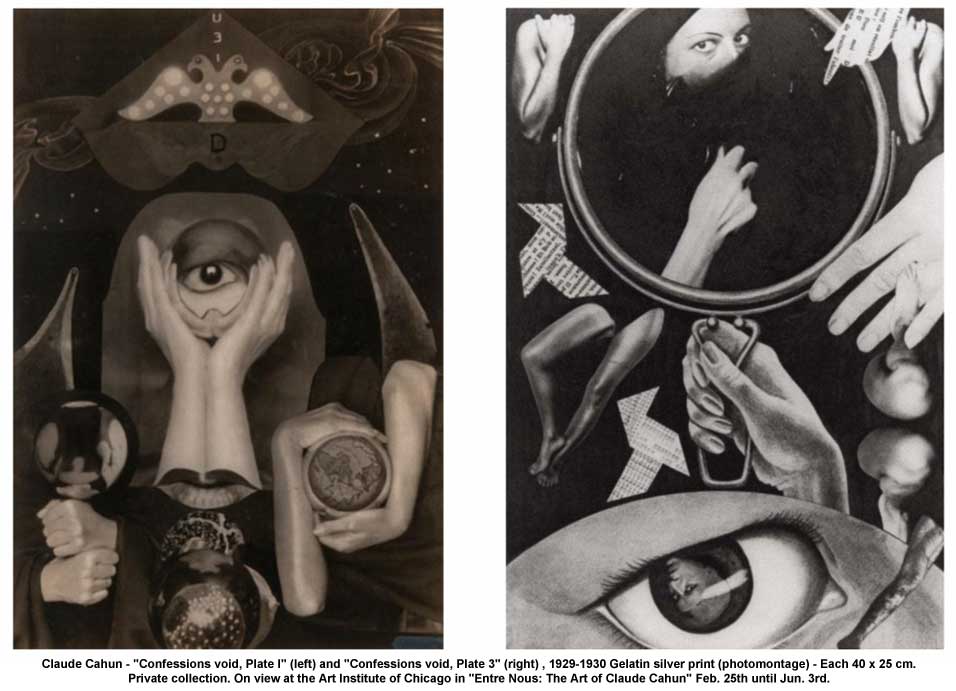

Dada photomontage

Photomontage is often used as a means of expressing political dissent. It was first used as a technique by the Dadaists in 1915 in their protests against the First World War.

Photomontage first emerged in the mid-1850s as experimental photographers aspired to create images that could rank alongside fine art. The idea of the composite image was thought to have been first proposed by the French photographer Hippolyte Bayard who wanted to produce a balanced image in which the subject was superimposed on a background that brought the two together in an idealized setting. Since a photograph was regarded as the record of truth, however, his approach attracted controversy amongst the photographic community who did not warm to the blatant misrepresentation of reality.

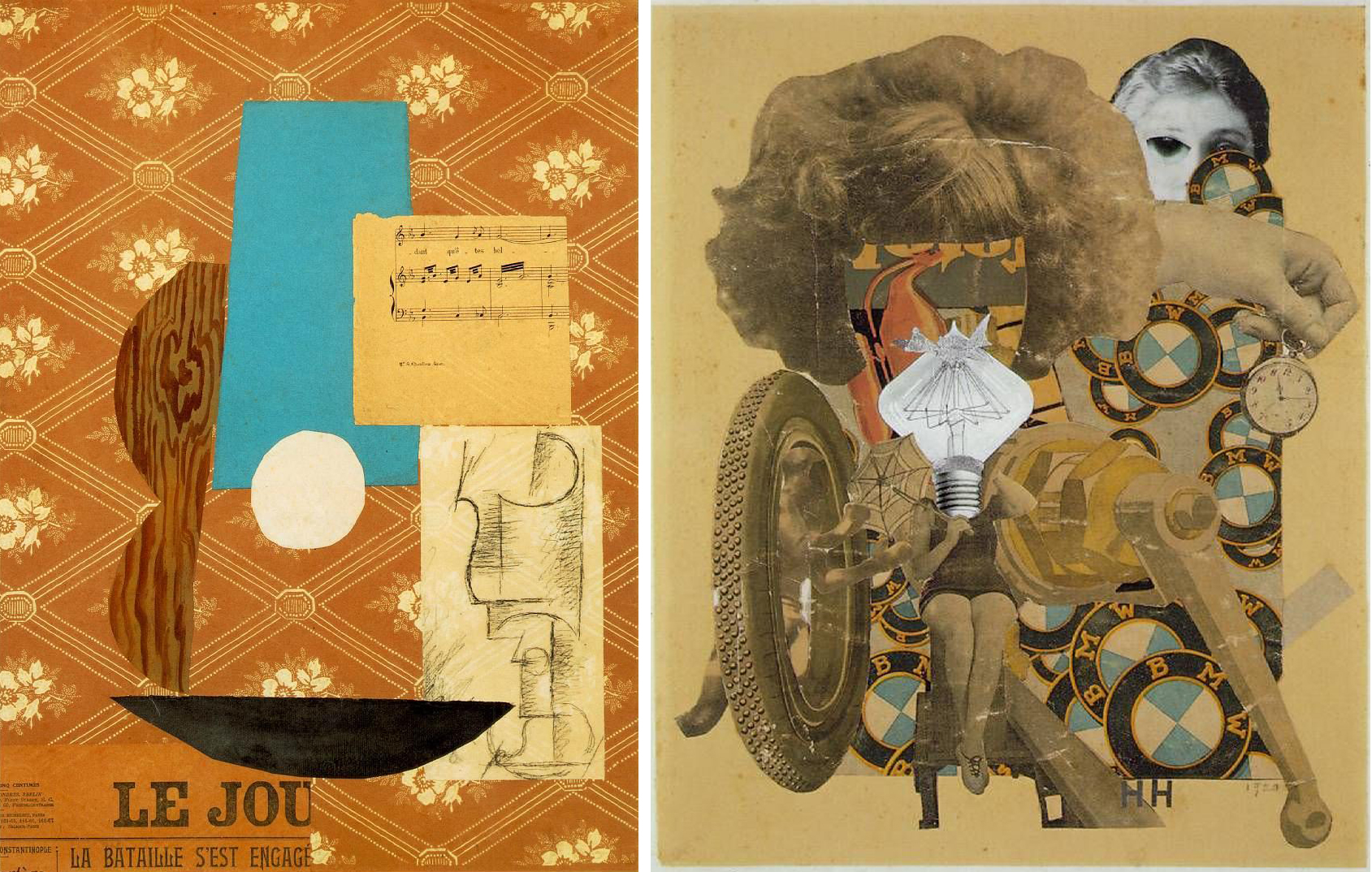

The first commercial photomontages were produced during the mid-Victorian era when the practice was given the name “combination printing” by Oscar Gustave Rejlander, a self-appointed artist in this new field. Rejlander started working in portraiture, but he also created notorious “erotic” artworks featuring circus models and child prostitutes. His famous Two Ways of Life (1857) combined over thirty images in a single photograph to create a moralistic allegory contrasting a life of sin with one of virtue. Showing two boys being offered guidance by the patriarch, the print initially caused controversy for its partial nudity. That objection notwithstanding, the print was a success and helped secure Rejlander’s admission into the Royal Photographic Society of London.

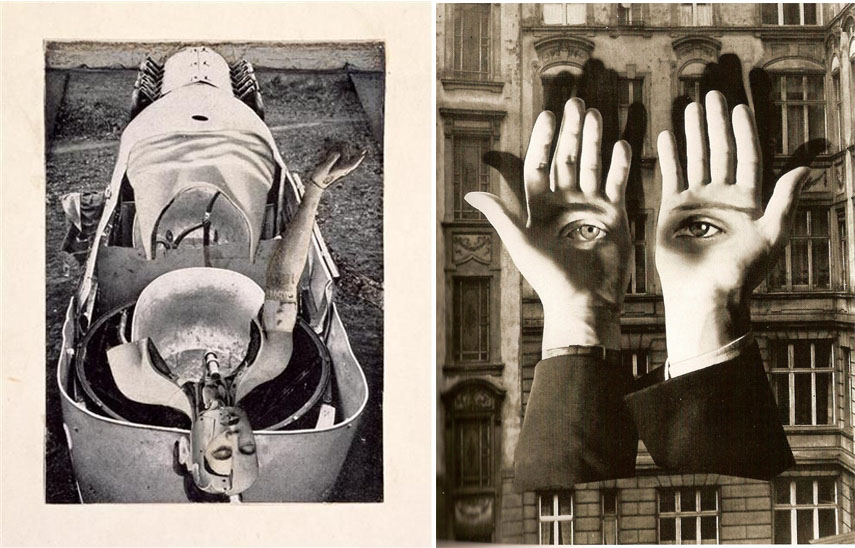

Dada artists are usually credited with pioneering the use of “non-narrative” photomontage. (Not without a little conceit) George Grosz reflected that “When John Heartfield and I invented photomontage in my South End studio at five o’clock on a May morning in 1916, neither of us had any inkling of its great possibilities, nor of the thorny yet successful road it was to take”. Hannah Höch, meanwhile, explained how she and her partner Raoul Hausmann came to adopt the idea, not from Heartfield or Grosz, but “from a trick of the official photographers of the Prussian army regiments [who] used to have elaborate oleo-lithographed mounts, representing a group of uniformed men with a barracks or a landscape in the background then inserted photographic portraits of the faces of their customers, generally coloring them later by hand”. Though these commercial efforts were intended to create a seamless illusion, Höch used the technique rather to draw attention to the absurdities and inequalities of modern German society.

Photomontage would become a dominant technique within the Berlin Dada movement, redefining the very role of the modern artist (as the Dadaists saw it at least). As Raoul Hausmann said, “We called [the] process ‘photomontage,’ because it embodied our refusal to play the part of the artist. We regarded ourselves as engineers, and our work as construction: we assembled our work, like a fitter”. The art critic Brian Dillon added that the technique established “the aesthetic of liberation, revolution, protest And in the hands of these artists it became intensely ideological, a defence in times of tyranny and a weapon against injustice”.

Constructivism

The idea of photographic formalism was the central tenet of Constructivism, and as art historian Craig Buckley remarked, while the “beginnings of avant-garde photomontage are commonly traced back to the context of Berlin Dada after World War I the technique was adopted almost simultaneously by constructivist artists and filmmakers in the Soviet Union”.

El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko, Gustav Klutis, Valentina Kulagina, and Varvara Stepanova (who defined photomontage in 1928 as “the assemblage of the expressive elements from individual photographs”) created photomontages that synthesized images with graphic design to support the Russian Revolution and the new Soviet Government. Constructivist works were inherently propagandist, as exemplified in Rodchenko’s posters which, with their bold colours and dynamic geometric design, transformed the art of graphic design into something revolutionary. El Lissitzky’s photomontages, which combined his photographs in multi-layered compositions, exemplified a more aesthetic Constructivist approach, while also influencing the New Vision movement, Bauhaus photography, and prominent artists such as László Moholy-Nagy.

Surrealism montage

Surrealism montage

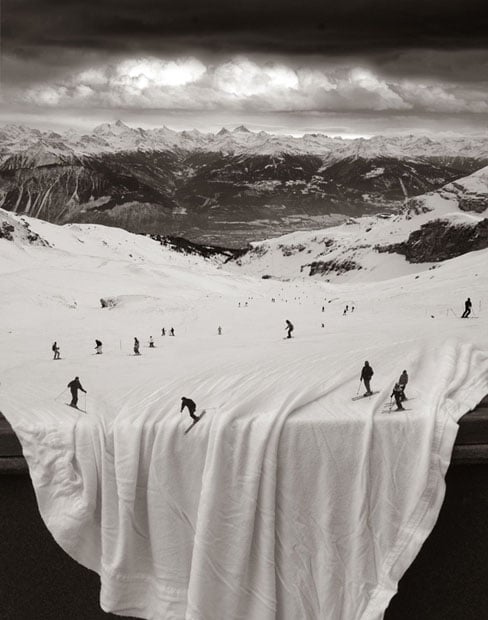

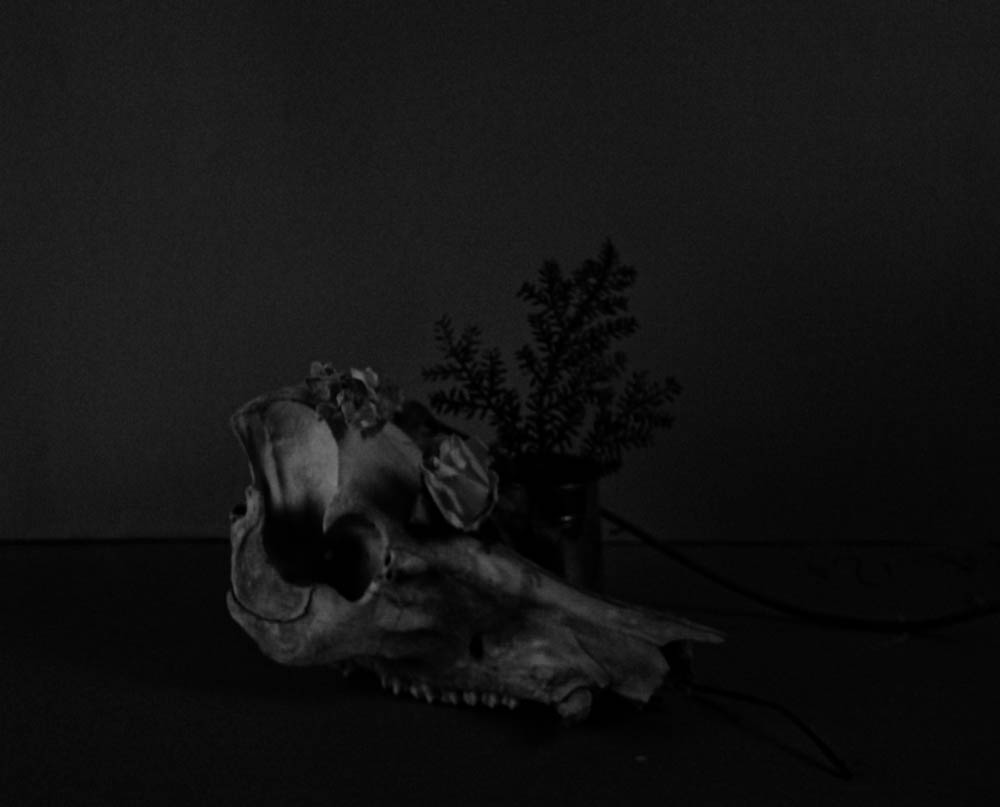

Photomontage was valued amongst Surrealists for its ability to create uncanny scenarios that disturbed and provoked by probing the human subconscious. Former Dada artists, such as Max Ernst, carried the technique over into the new movement. Ernst described photomontage as “the systematic exploitation of the accidentally or artificially provoked encounter of two or more foreign realities on a seemingly incongruous level – and the spark of poetry that leaps across the gap as these two realities are brought together”. Surrealism also pioneered collaborative photomontage through the cadaver exquis (exquisite corpse) technique whereby the various participants contributed to the piece while remaining unaware of the origins of the previous contribution. Some Surrealists, such as Dora Maar, were known primarily for their photomontage, though many leading Surrealists, including René Magritte, Man Ray, and Salvador Dalí included the technique in their repertoire. Their works also exercised an important international influence, as seen, for instance, in Harue Koga’s Sea (1929) which helped pioneer Surrealism in Japan. He too used the collage technique to create what have been called “photomontage paintings”.

Between 1899 and 1909 the grammars of cinema entered a chaotic period of experimentation in which filmmakers hurried to test the possibilities of editing individual shots of film together into something more meaningful. Between 1909 and 1919 one D. W. Griffiths almost singlehandedly developed the method of montage that gave rise to the Classical Realist Narrative; known otherwise as the Classical Hollywood Film. A profoundly problematic figure for historians given his supremacist and pious worldview, through films like The Birth of a Nation (1915) he devised a system of montage that was so sophisticated he placed the spectator in the world of a feature length film.