Portrait photography has a long and varied history that dates back to 1839. Portrait photography became popular through early images of famous people and evolved as a way to preserve history. A portrait is a photograph of a person taken by another person, while a self-portrait is a picture one takes of themselves.

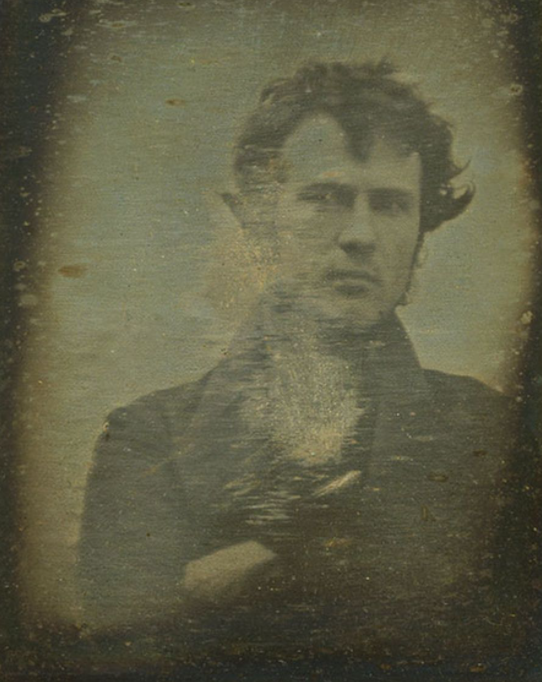

The invention of photography can be credited to Louis Daguerre, who first introduced the concept to the French Academy of Sciences in 1839. That same year, Robert Cornelius produced what’s considered the first photographic self-portrait.

Portrait studios started springing up the next year. These early studios weren’t an instant hit, as a majority of the public was still unsure of the new medium.

To dissuade their fears, photographers sought to capture images of famous people, such as Abraham Lincoln and Charles Dickens. Portrait photography became a way for people to have an image of a loved one or a celebrity without having to commission an artist to paint a time-consuming portrait.

PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHERS THROUGHOUT HISTORY

ROBERT CORNELIUS

(March 1, 1809 – August 10, 1893)

Robert Cornelius was an American photographer and pioneer in the history of photography. He designed the photographic plate for the first photograph taken in the United States, an image of Central High School taken by Joseph Saxton in 1839. His self image taken in 1839 is the first known photographic portrait of a human taken in the United States. He operated two of the earliest photography studios in the United States between 1841 and 1843 and implemented innovative techniques to significantly reduce the exposure time required for portraits.

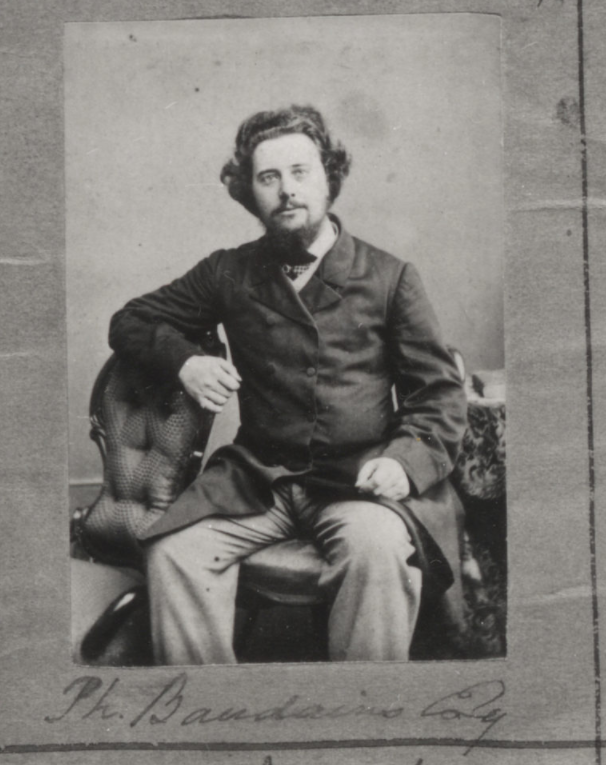

HENRY MULLINS

(1818-1880)

Henry Mullins is one of the most prolific photographers represented in the Societe Jersiase Photo-Archive, producing over 9,000 portraits of islanders from 1852 to 1873 at a time when the population was around 55.000. The record we have of his work comes through his albums, in which he placed his clients in a social hierarchy. The arrangement of Mullins’ portraits of ‘who’s who’ in 19th century Jersey are highly politicised.

Henry Mullins started working at 230 Regent Street in London in the 1840s and moved to Jersey in July 1848, setting up a studio known as the Royal Saloon, at 7 Royal Square. Here he would photograph Jersey political elite (The Bailiff, Lt Governor, Jurats, Deputies etc), mercantile families (Robin, Janvrin, Hemery, Nicolle ect.) military officers and professional classes (advocates, bankers, clergy, doctors etc).

His portrait were printed on a carte de visite as a small albumen print, (the first commercial photographic print produced using egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper) which was a thin paper photograph mounted on a thicker paper card. The size of a carte de visite is 54.0 × 89 mm normally mounted on a card sized 64 × 100 mm. In Mullins case he mounted his carted de visite into an album. Because of the small size and relatively affordable reproducibility cartes de visite were commonly traded among friends and visitors in the 1860s. Albums for the collection and display of cards became a common fixture in Victorian parlors. The immense popularity of these card photographs led to the publication and collection of photographs of prominent persons. He also arranged single portraits into diamond cameos.

Some headshots by Mullins of both Jersey men and women were produced as vignette portrait which was a common technique used in mid to late 19th century.

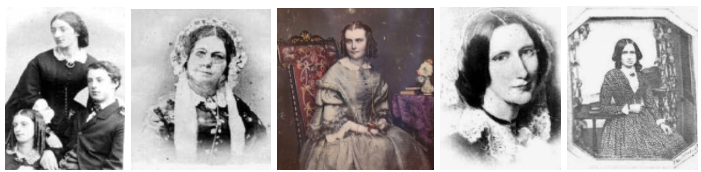

JULIA MARGARET CAMERON

(11 June 1815-26 January 1879)

Julia Margaret Cameron was a British photographer who is considered one of the most important portraitists of the 19th century. She is known for her soft-focus close-ups of famous Victorian men and for illustrative images depicting characters from mythology, Christianity, and literature

Cameron was often criticized by the photographic establishment of her day for her supposedly poor technique: some of her pictures are out of focus, her plates are sometimes cracked, and her fingerprints are often visible, however Cameron was an amateur- the camera she used being a gift from her son-in-law.

Having lived in India and London, Cameron’s family had recently moved to the Isle of Wight, a popular location for Britain’s cultural elite—residents included essayist, philosopher, and historian Thomas Carlyle, author Charles Dickens, inventor John Herschel, and poet Alfred Lord Tennyson. Cameron photographed these famous tenants and anyone else who would let her. Such local figures as the postman, as well as her own family and servants, appear in many of her images.

Her tenacity and eccentricity eventually became well known; she allegedly followed promising-looking people on the streets until they consented to model for her. A well-read, educated woman, she often pressed her subjects into posing for pastoral, allegorical, historical, literary, and biblical scenes, such as in Madonna with Children (1864). In this photograph, she transforms Mary Kellaway, a local dressmaker, and Elizabeth and Percy Keown, children of a gunner in the Royal Army, into figures in an enduring art historical scene.

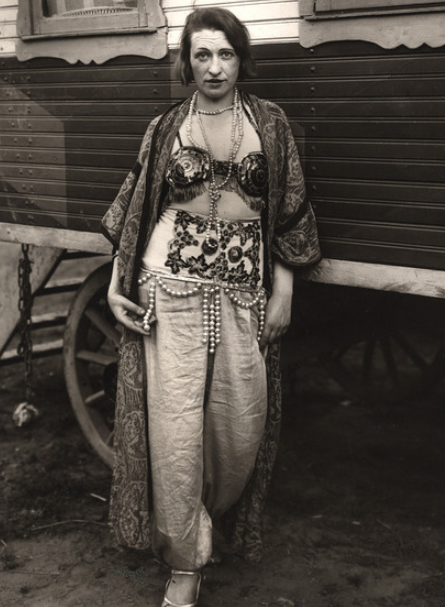

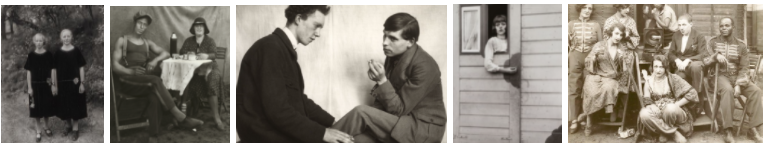

AUGUST SANDER

(November 17, 1876 -April 20, 1964)

August Sander was a German portrait and documentary photographer. Sander’s first book Face of our Time was published in 1929. Sander has been described as “the most important German portrait photographer of the early twentieth century”.

His photos are similar to modern street photography, capturing people in their natural environment .

August Sander was a German photographer whose work documented the society he lived in. Lauded as one the most-important portrait photographers of the early 20th century, Sander focused his gaze on bricklayers, farmers, bakers, and other members of the community. “Nothing seemed to me more appropriate than to project an image of our time with absolute fidelity to nature by means of photography,” he once declared. “Let me speak the truth in all honesty about our age and the people of our age.”

Born in Herdorf, Germany on November 17, 1876, Sanders learned photography during his military service in the city of Trier. By 1910, he had moved to a suburb of Cologne, spending his days biking along the roads to find people to photograph. By the time the Nazi regime rose to power in the 1930s, Sander was considered an authority on photography and recognized for his book Face of Our Time (1929).

During this era, he faced both personal persecution and the systematic destruction of his work. Following the death of his son in 1944, and the destruction of his work in 1946, Sander practically ceased photography altogether. He died in Cologne, Germany on April 20, 1964 at the age of 87. Today, the artist’s works are held in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne, among others.

THOMAS RUFF

(February 10, 1958-)

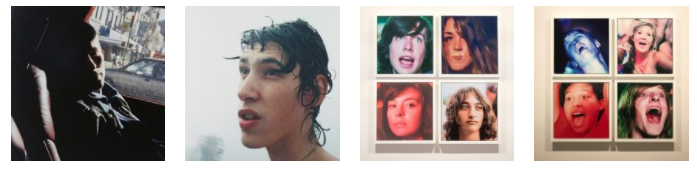

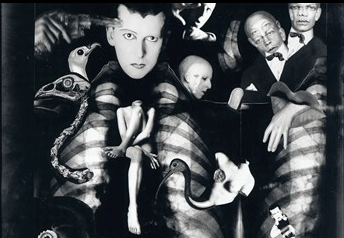

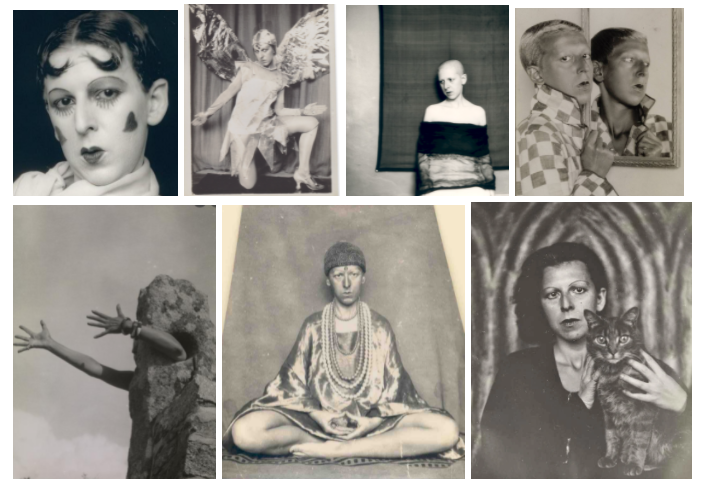

Thomas Ruff portrays works that examine complex relationship between photography, political propaganda, and the possibilities of digital manipulation.

Born in 1958 in Zell am Harmersbach, Germany, Thomas Ruff attended the Staatlichen Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf from 1977 to 1985. Ruff rose to international prominence in the late 1980s as a member of the Düsseldorf School, a group of young photographers who had studied under Bernd and Hilla Becher and became known for their experimental approach to the medium and its evolving technological capabilities.

Ruff in particular made a radical break with the style of his teachers, establishing a distinct approach to conceptual photography through a variety of strategies, including the use of color, the purposeful manipulation of source imagery—originally through manual retouching techniques and eventually through digital methods—and the enlargement of the photographic print to the scale of monumental painting.

Working in discrete series, Ruff has since utilized these methods to conduct an in-depth examination of a variety of photographic genres, including portraiture, the nude, landscape, and architectural photography, among others. Highly influential to subsequent generations of photographers, Ruff’s overarching inquiry into the “grammar of photography” accounts for not only his heterogeneous subject matter, but also the extreme variation of technical means used to produce his series, ranging from anachronistic devices to the most advanced computer simulators and covering nearly all ground in between