The dead pan aesthetic

Deadpan photography goes back all the way to the 1920s. It’s a very distinct style of photography that has somehow made its way into the 21st century, quietly and persistently influencing you in a way you might not even be aware of.

According to sources the origins of the word “Deadpan” can be traced to 1927 when Vanity Fair Magazine compounded the words dead and pan, a slang word for a face, and used it as a noun. In 1928 the New York Times used it as adjective to describe the work of Buster Keaton.

It is less clear when it was first used to describe the style of photography associated with Edward Ruscha, Alec Soth, Thomas Ruff and many others. Charlotte Cotton devotes a complete chapter to Deadpan in The Photograph as Contemporary Art and much that has been written since references that essay.

In summary Deadpan photography is a cool, detached, and unemotional presentation and, when used in a series, usually follows a pre-defined set of compositional and lighting rules.

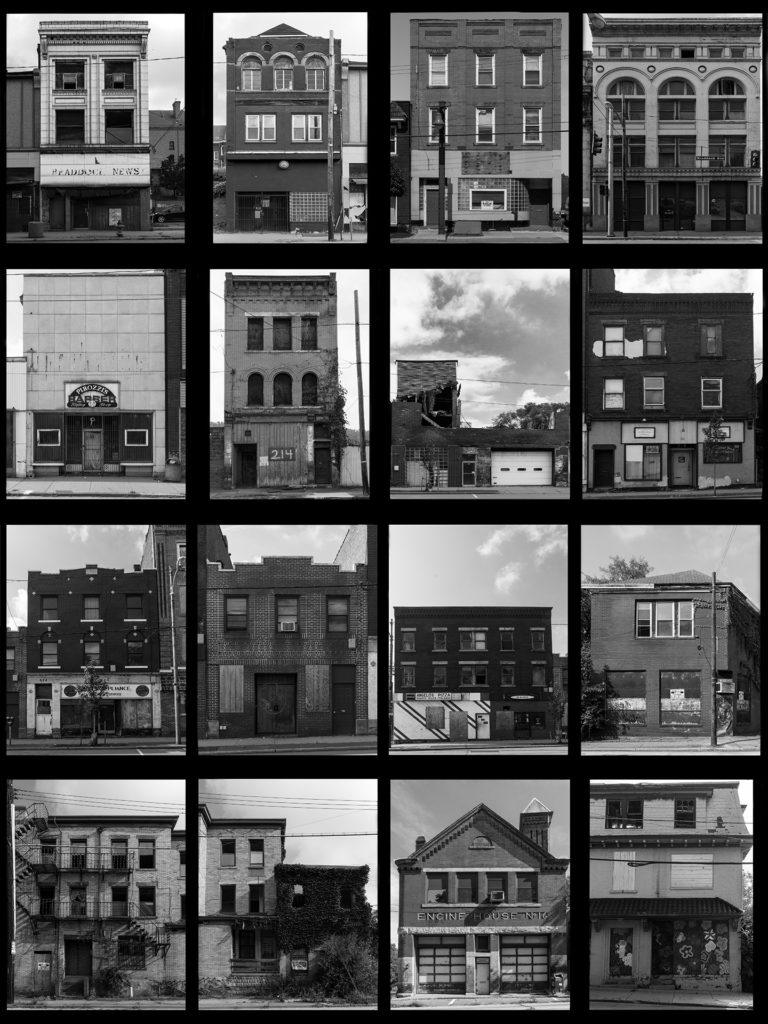

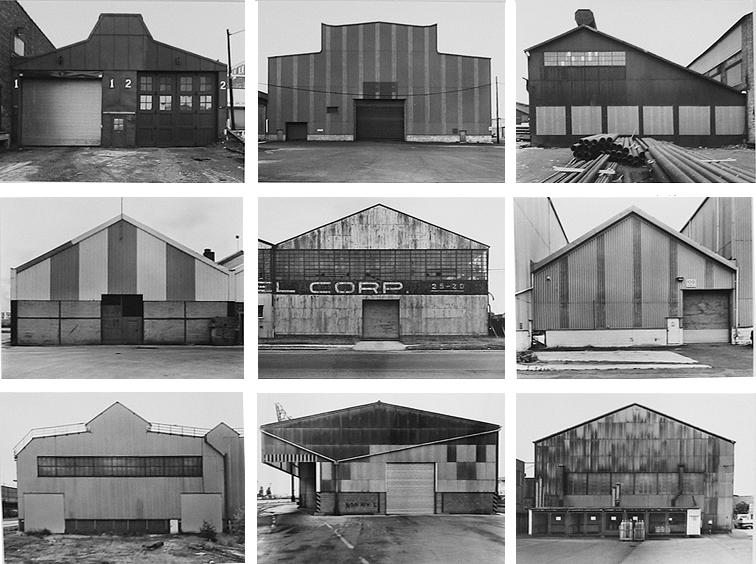

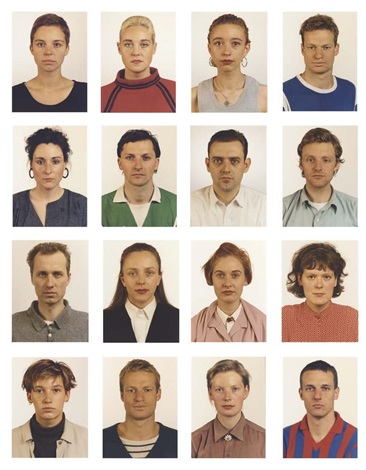

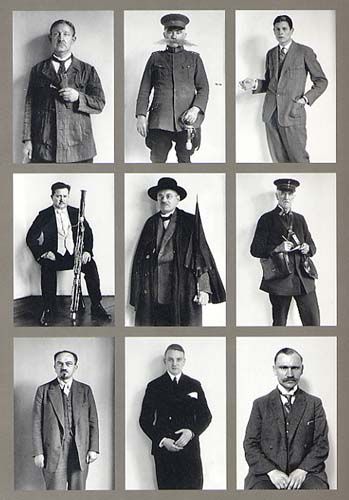

This style originated in Germany and is descended from Neue Sachlichkeit, New Objectivity, a German art movement of the 1920s that influenced the photographer August Sander who systematically documented the people of the Weimar Republic . Much later, in the 1970s, Bernd and Hilla Becher, known for their devotion to the principles of New Objectivity, began to influence a new generation of German artists at the Dusseldorf School of Photography (4). These young German photographers included Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky, Candida Hofer and Thomas Ruff. The Bechers (4 & 5) are best remembered for their studies of the industrial landscape, where they systematically photographed large structures such as water towers, coal bunkers or pit heads to document a soon-to-disappear landscape in a formalistic manner as much akin to industrial archeology as art. The Bechers’ set of “rules” included clean, black and white pictures taken in a flat grey light with straight-on compositions that perfectly lent themselves to their presentation methodology of large prints containing a montage of nine or more similar objects to allow the study of types (typology) in the style of an entomologist.

The deadpan aesthetics is considered a technically perfect photograph which depicts a landscape, still life or a person by a direct centred composition. The photographs usually have a single central theme (a mining tower, face, mound of clay, etc.), the background is usually unimportant (which does not

apply for more sociologically oriented concepts), ignored or is neutral and sterile. Other photographs are based on the richness of motifs (immense landscape, crowd of people, clump of trees, etc.), in which it is impossible to identify the main motif. The first paradigm was denoted by Robert Silverio as a negation of composition and the second one as a disintegration of composition.

Above all the other formal attributes, there is a high level of modality, based on which a photography has an impression of being very realistic and believable. Colours are slightly desaturated, dull. Composition gestures are constrained or minimized. Photographs seem depleted, describing a given reality without unambiguous attitude of an author. However, no photograph can be purely descriptive and unemotional, although, the photographer may seek to marginalize their subjective input and focus their attention to their objectiveness. Besides high-level craftsmanship, the visual language of the deadpan aesthetics is mainly built on the absence of a photographer’s emotional input.

They deliberately give up their emotional or political view and keep a certain distance from the theme.

However, paying attention to a strongly emotional theme is not totally excluded. Such emotional theme can have an emotional

impact on a photographer, but they still keep their distance when taking the photograph and do not involve their emotions in the photograph. In that way, thanks to the neutral attitude of the author and the way of interpretation which is

cold and objective, the recipient is provided with a strong emotional content of the photograph. When analysing deadpan photographs, it is important to perceive their content from a wider, more comprehensive point of view. Creation of such photographs results from an approach which is more anthropological and scientific than critical and artistic. Formal characteristics of the deadpan aesthetics can be described as means of expression of scientific and systematic methodology in photography.

Typologies

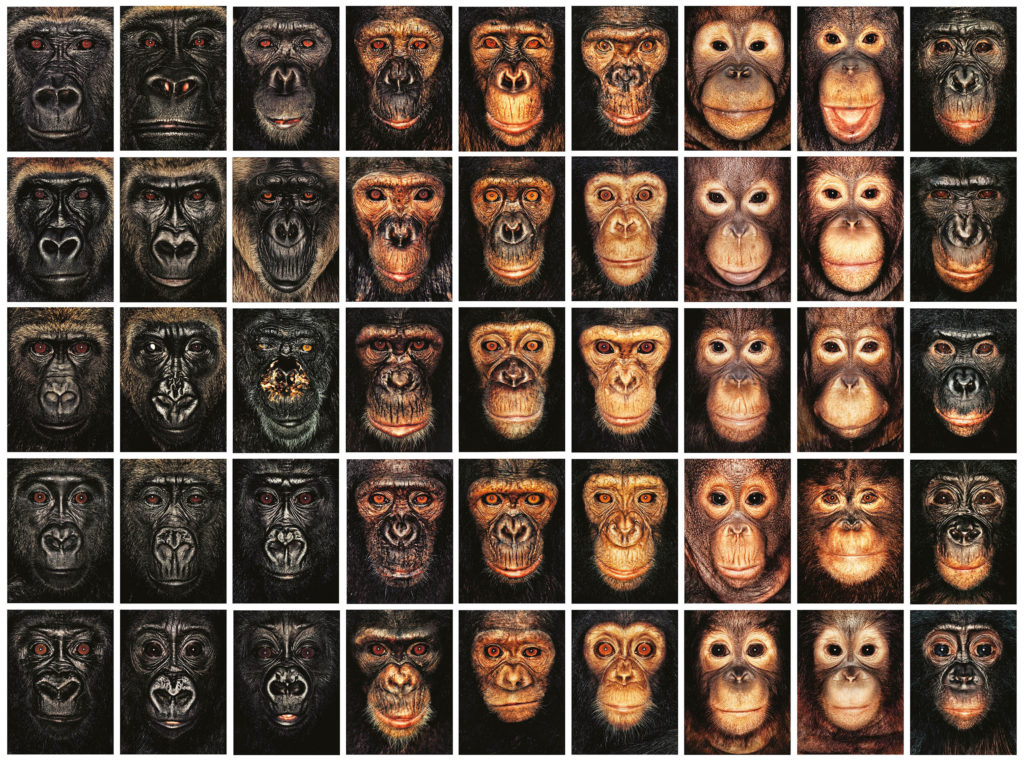

A photographic typology is a single photograph or more commonly a body of photographic work, that shares a high level of consistency. This consistency is usually found within the subjects, environment, photographic process, and presentation or direction of the subject.

One of the golden rules in typological photography is consistency. Not only do you need to photograph a certain type of subject, you need to create a body of work that clearly points to the differences and similarities between each one.

The German artists Bernd and Hilla Becher, who began working together in 1959 and married in 1961, are best known for their “typologies”—grids of black-and-white photographs of variant examples of a single type of industrial structure.

They began collaborating together in 1959 after meeting at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1957. Bernd originally studied painting and then typography, whereas Hilla had trained as a commercial photographer.

They took photos of Industrial structures including water towers, coal bunkers, gas tanks and factories. Their work had a documentary style as their images were always taken in black and white. Their photographs never included people.

The Becher’s were influenced by the work of earlier German photographers linked to the New Objectivity movement of the 1920s such as August Sander, Karl Blossfeldt and Albert-Renger-Patzsch.

August Sander was a German portrait and documentary photographer. Sander’s first book Face of our Time was published in 1929. Sander has been described as “the most important German portrait photographer of the early twentieth century”.

Karl Blossfeldt early photographs reveal an interest in the typology of plant forms which was to become a fundamental concern of his later work. He shot his plants in front of natural backgrounds, lit them with weak daylight whenever possible, and used either a vertical or horizontal perspective.

Up close

Bruce Gilden is an American street photographer. He is best known for his candid close-up photographs of people on the streets of New York City, using a flashgun. He has had various books of his work published, has received the European Publishers Award for Photography and is a Guggenheim Fellow.

Right from childhood, he has always been fascinated by the life on the streets and the complicated and fascinating motion it involves, and this was the spark that inspired his first long-term personal projects, photographing in Coney Island and then during the Mardi Gras in New Orleans.

David Goldblatt was a South African photographer noted for his portrayal of South Africa during the period of apartheid. After apartheid had ended he concentrated more on the country’s landscapes.

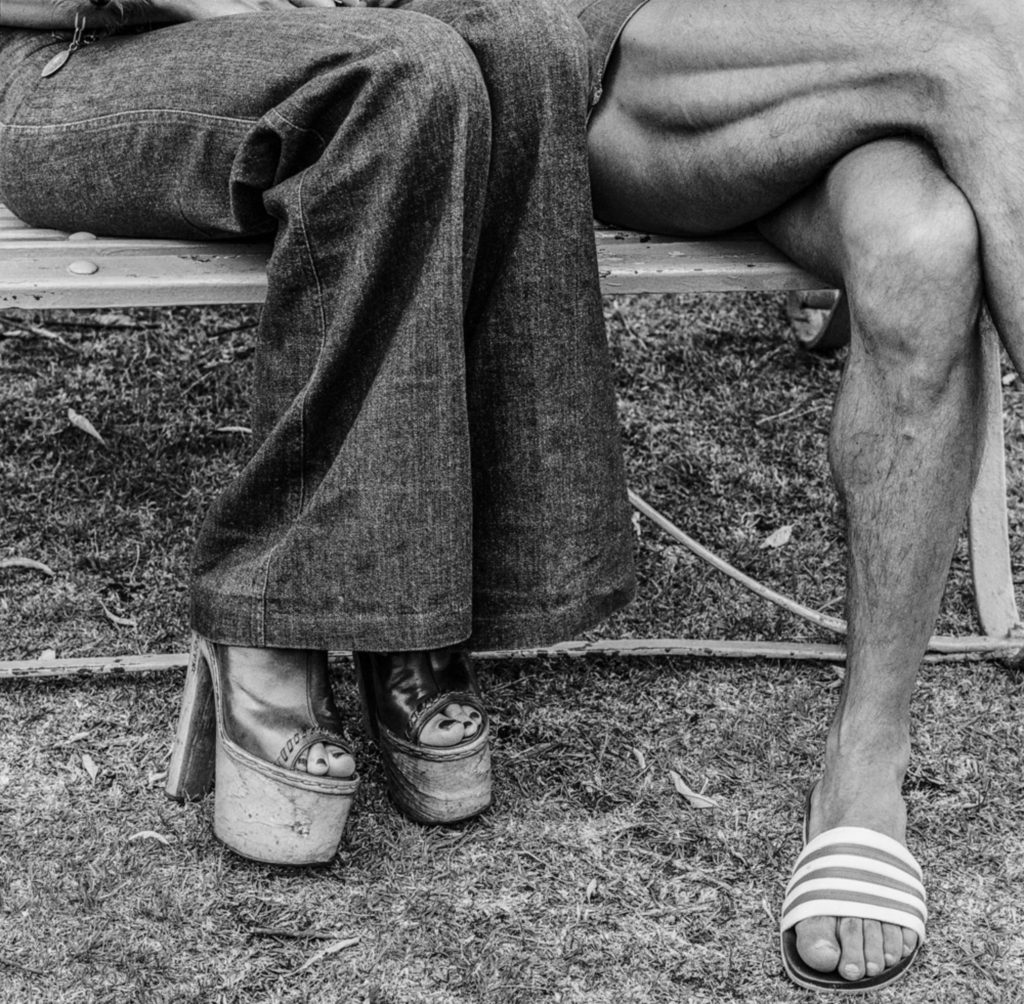

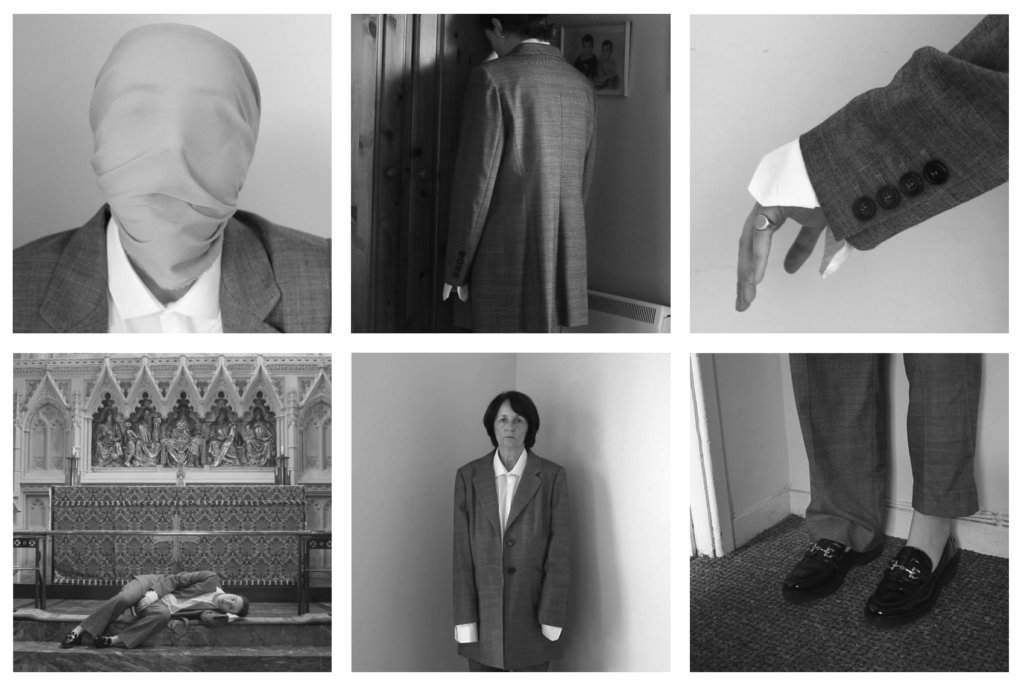

Following a series of portraits of his compatriots made in the early 1970s, photographer David Goldblatt, for a very short and intense period of time, naturally turned to focusing on peoples’ particulars and individual body languages “as affirmations or embodiments of their selves.” Goldblatt’s affinity was no accident: Working at his father’s men’s outfitting store in the 1950s, his awareness of posture, gesture and proportion technical as it was formed early and would accompany him throughout his life.

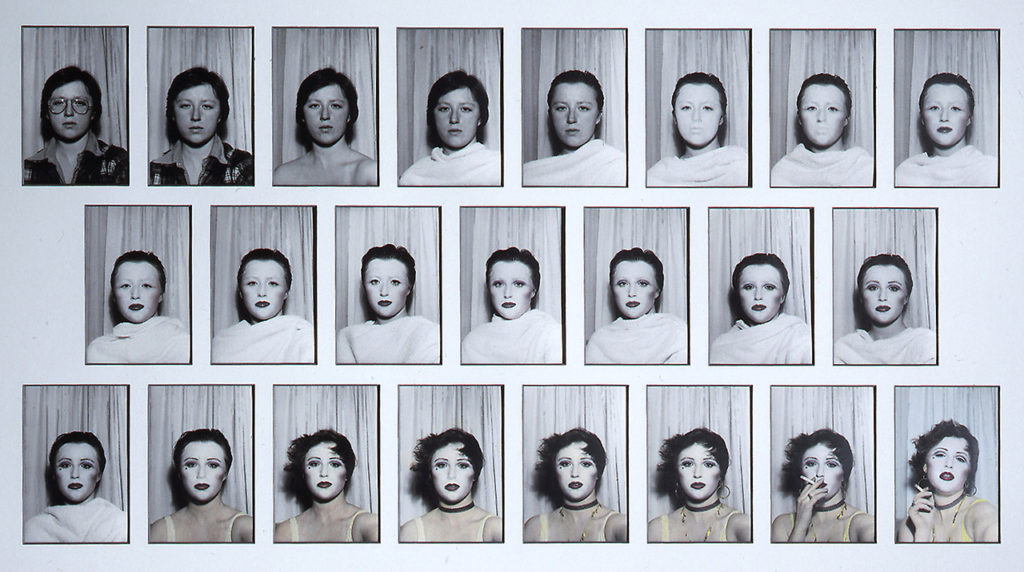

Sequence / grid

A sequence, sometimes called an image sequence, is created by using editing software such as Photoshop, to combine all photos from a camera burst into a single image. This single image then shows the path of an object or subject.

This technique is often used in action sports photography in order to depict an athlete performing a trick or extreme feat that would be difficult to document or understand with a single frame photo. A sequence is created by shooting with your camera in burst mode to fire off a quick series of back-to-back photos.

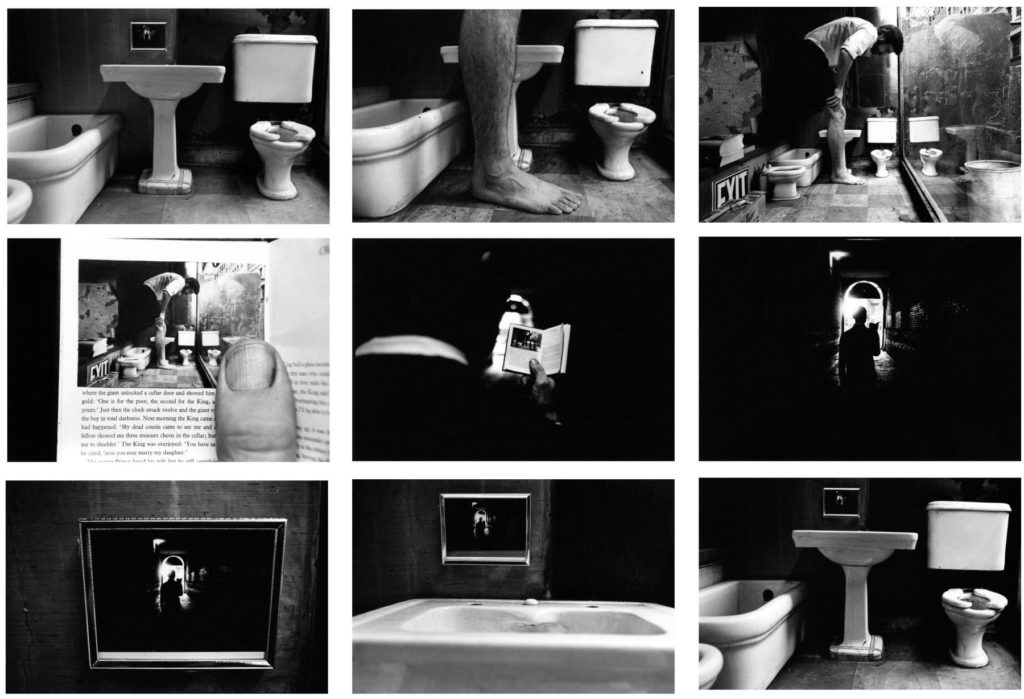

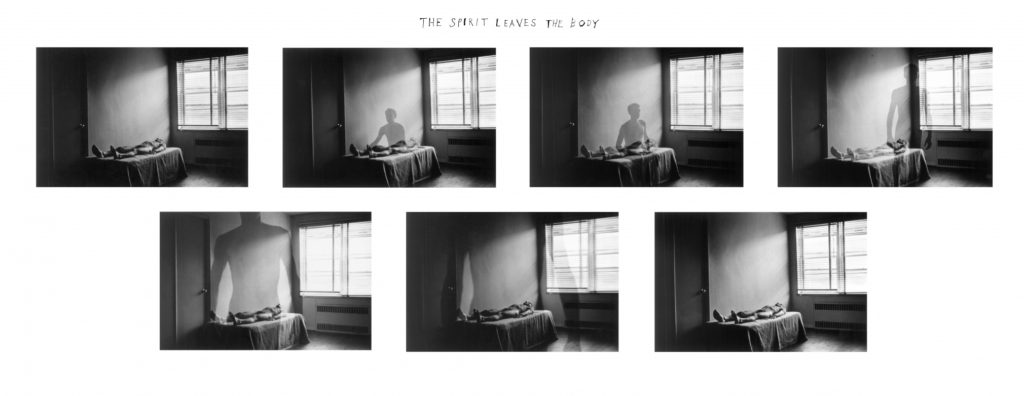

Duane Michals (b. 1932, USA) is one of the great photographic innovators of the last century, widely known for his work with series, multiple exposures, and text. Michals first made significant, creative strides in the field of photography during the 1960s. In an era heavily influenced by photojournalism, Michals manipulated the medium to communicate narratives. The sequences, for which he is widely known, appropriate cinema’s frame-by-frame format. Michals has also incorporated text as a key component in his works. Rather than serving a didactic or explanatory function, his handwritten text adds another dimension to the images’ meaning and gives voice to Michals’s singular musings, which are poetic, tragic, and humorous, often all at once.

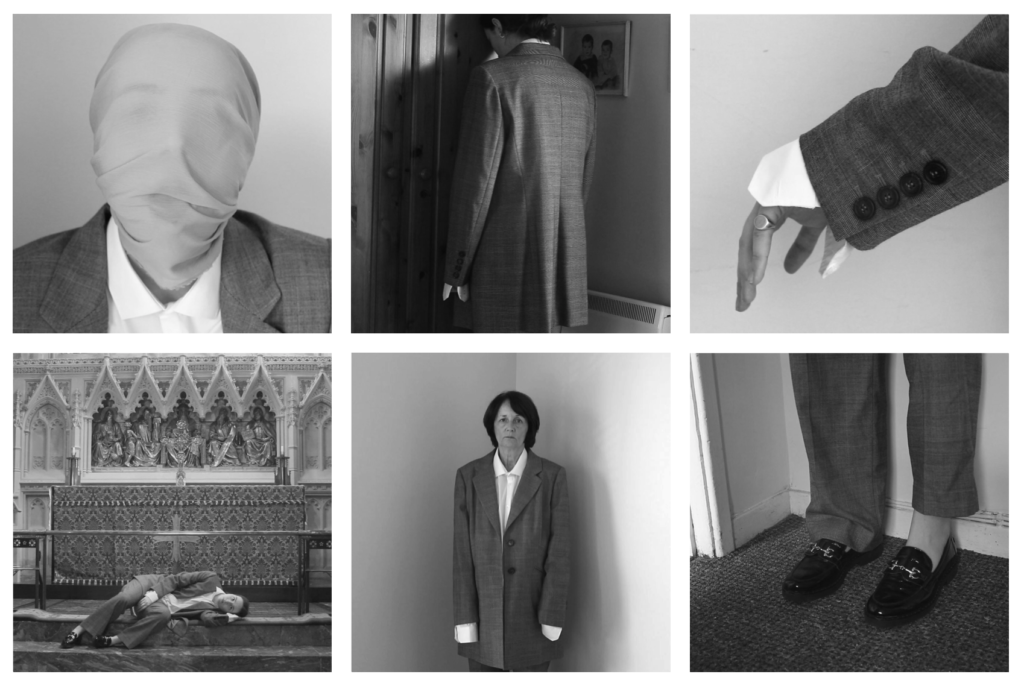

Shannon O’Donnell: That’s Not The Way The River Flows (2019) is a photographic series that playfully explores masculinity and femininity through self-portraits. The work comes from stills taken from moving image of the photographer performing scenes in front of the camera. This project aims to show the inner conflicts that the photographer has with identity and the gendered experience. It reveals the pressures, stereotypes and difficulties faced with growing up in a heavily, yet subtly, gendered society and how that has impacted the acceptance and exploration of the self.

Tracy Moffatt: The nine images in Something More tell an ambiguous tale of a young woman’s longing for ‘something more’, a quest which brings dashed hopes and the loss of innocence. With its staged theatricality and storyboard framing, the series has been described by critic Ingrid Perez as ‘a collection of scenes from a film that was never made’. While the film may never have been made, we recognise its components from a shared cultural memory of B-grade cinema and pulp fiction, from which Moffatt has drawn this melodrama. The ‘scenes’ can be displayed in any order – in pairs, rows or as a grid – and so their storyline is not fixed, although we piece together the arc from naïve country girl to fallen woman abandoned on the roadside in whatever arrangement they take. Moffatt capitalises on the cinematic device of montage, mixing together continuous narrative, flashbacks, cutaways, close-ups and memory or dream sequences, to structure the series, and relies on our knowledge of these devices to make sense and meaning out of the assemblage.

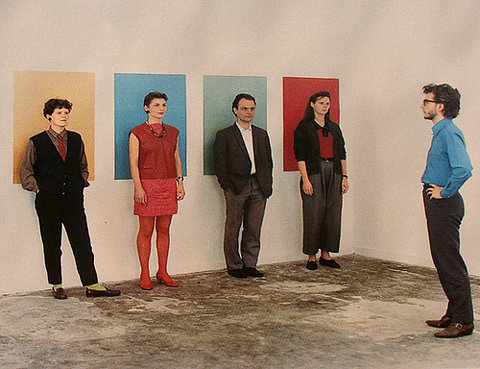

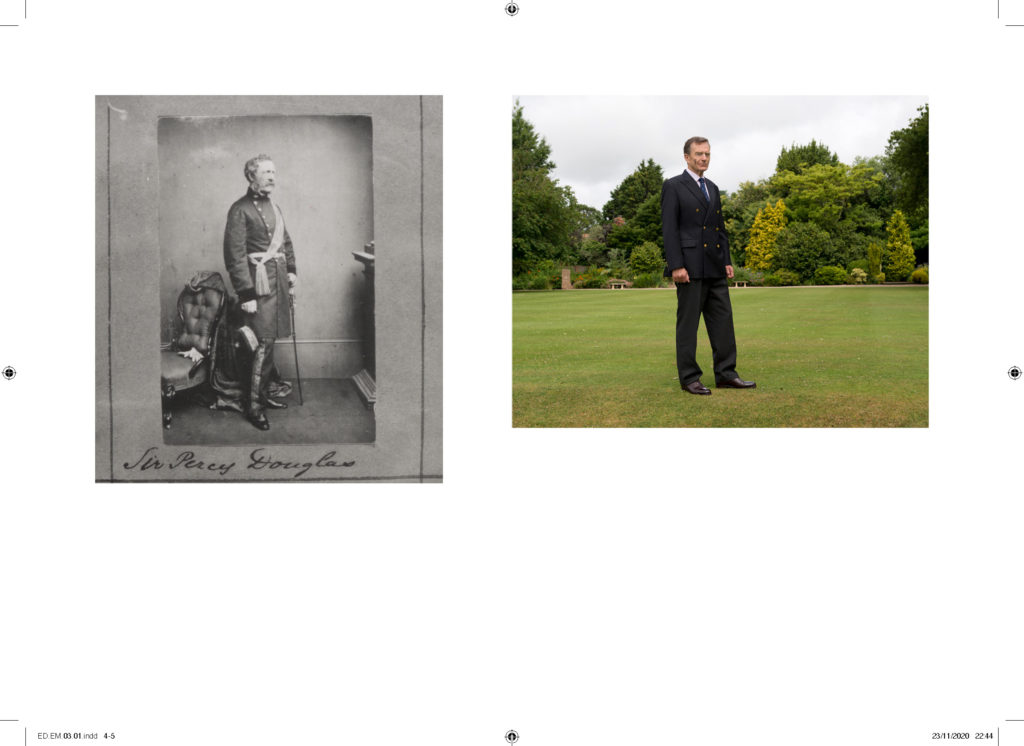

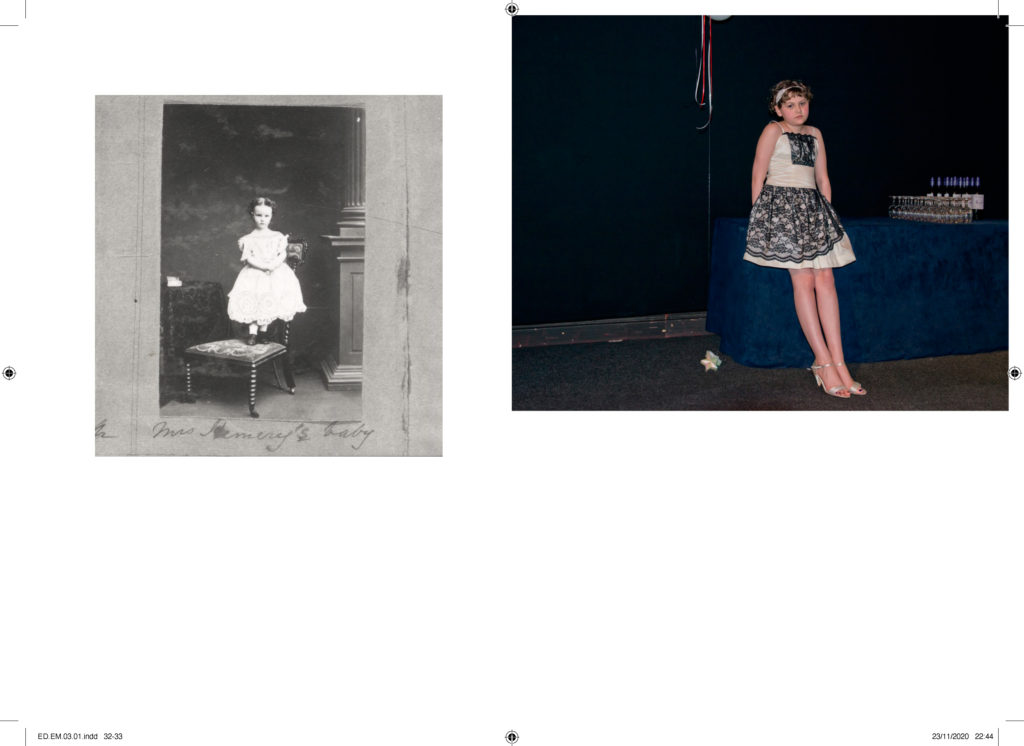

Juxtaposition

Juxtaposition is placing two images together to show contrast or similarities. For inspiration look at some of the page spreads from ED.EM.03 where pairings between portraits of Henry Mullins and Michelle Sank are juxtaposed to show comparison/ similarities/ differences between different social and professional classes in Jersey mid-19th century and early 21 st century.