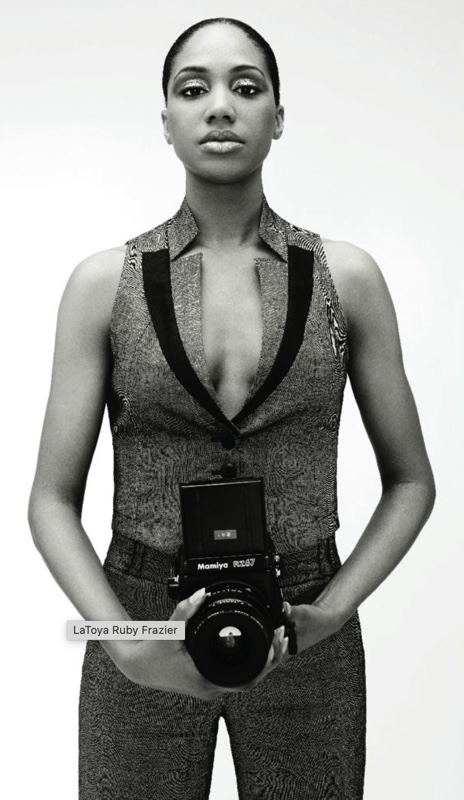

LaToya Ruby Frazier was born in 1982 in Braddock, Pennsylvania, and currently lives and works in Chicago. An artist and activist, LaToya Ruby Frazier uses photography, video, and performance to document personal and social histories in the United States, specifically the industrial heartland. Having grown up in the shadow of the steel industry, Frazier has chronicled the healthcare inequities and environmental crises faced by her family and her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. The artist employs a radically intimate, black-and-white documentary approach that captures the complexity, injustice, and simultaneous hope of the Black American experience, often utilizing her camera and the medium of photography as an agent for social change. Her 2016 Flint is Family project traces the lives of three generations of women living through the water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

“Flint is Family”

In 2016, LaToya Ruby Frazier spent five months living in Flint, Michigan with three generations of women–the poet Shea Cobb, her mother Renee, and daughter Zion–observing their day-to-day lives as they endured one of the most devastating ecological disasters in US history: the water crisis in their hometown. The artistic result of Frazier’s time there is reflected in the works presented in “Flint is Family,” opening August 2019 at the Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University.

“Through photographs, videos, and text I use my artwork as a platform to advocate for others, the oppressed, the disenfranchised,” says Frazier. In “Flint is Family,” Frazier explores at the level of community, the effects of the water crisis in Flint–where black residents make up 54% of the population and 40% of the population lives below the poverty line. “When I encounter an individual or family facing inequality, I create visibility through images and story-telling to expose the violation of their rights.”

By portraying the daily struggles of the Cobb family, Frazier used a tight focus to create a story about the impact of a systemic problem disproportionately affecting marginalized communities. Citing the social documentary work of Gordon Parks’ and Ralph Ellison’s 1948 “Harlem is Nowhere”–which highlighted the social and economic effects of racism and segregation–as an influence, Frazier rejected the voyeuristic photographs that emerged from outside media sources and instead collaborated closely with her subjects through photographs, capturing intimate moments along with the myriad challenges the family faced without access to clean water. In September 2016, Frazier published her images of Flint in Elle magazine in conjunction with a special feature on the water crisis. Like Parks, Frazier used the camera as a vehicle and agent of social change.

“By hosting the Louisiana premiere of Frazier’s work at the Newcomb Art Museum,” says Monica Ramirez-Montagut, museum director, “we are bringing meaningful, enriching, and transformative exhibitions of socially-engaged art that explores the concerns of communities both on and off campus, as well as recognizing underrepresented communities and the contributions of women to the field. Frazier’s artistic practice centers on the nexus of social justice and cultural change and tells an important story of the American experience that certainly echoes with our own Louisiana environmental crisis and pollution.”

“The Notion of Family”

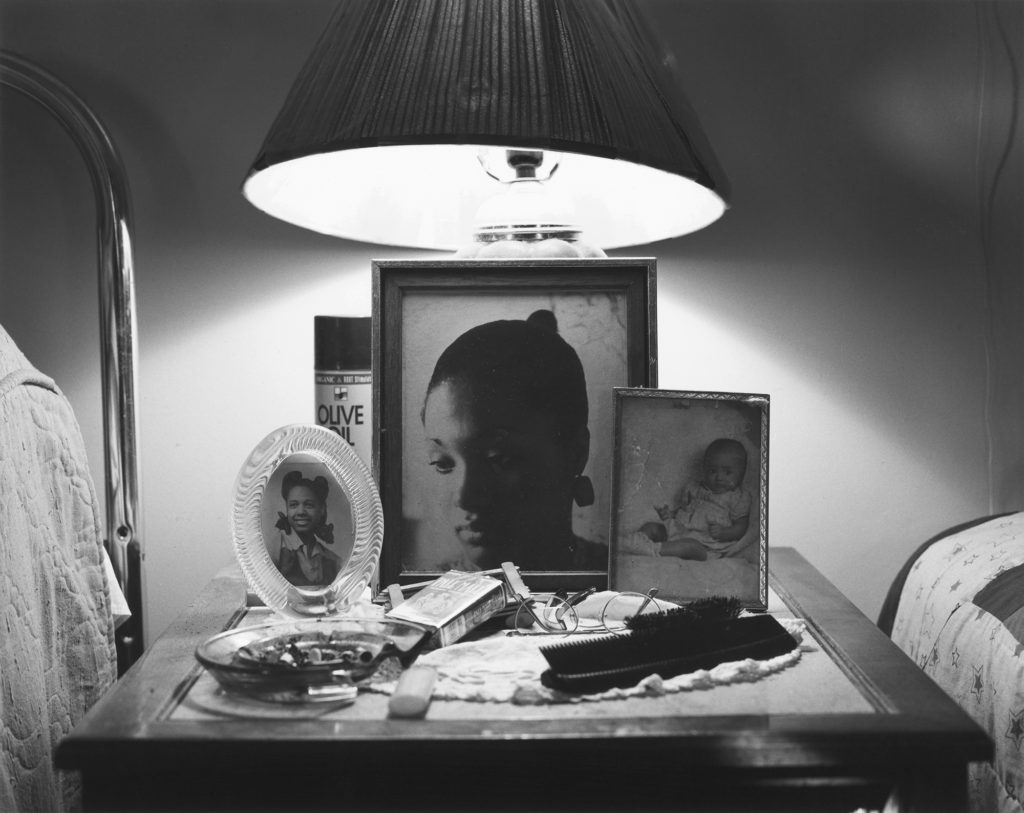

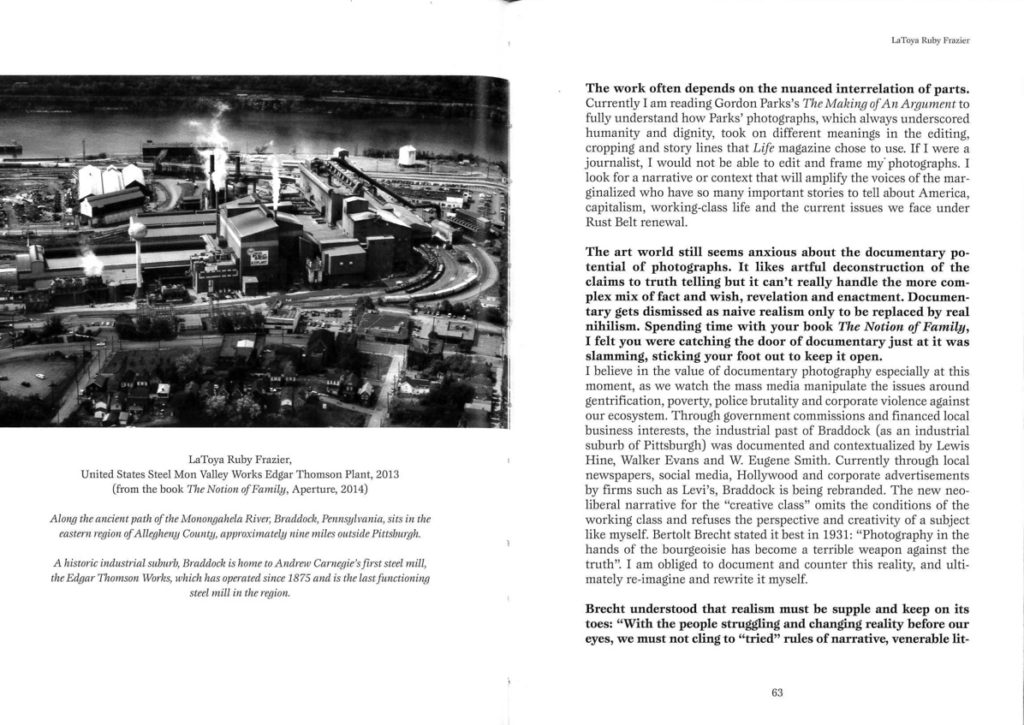

In 2015, her first book about how she, her mother, and grandmother survived environmental racism in historical steel mill town Braddock, Pensylvania, The Notion of Family, received the International Center for Photography Infinity Award. The Notion of Family, documents the decline of Braddock, Pennsylvania—a once-prosperous steel-mill town that employed generations of African American workers—alongside the hardships of Frazier’s family, who grew up there. Issues of class and race underscore the mostly black-and-white photographs in the collection, which is arranged as a kind of family album: intimate, collaboratively produced portraits of Frazier and her mother in mirrors and on beds, are presented with derelict scenes of collapsed buildings, vacant lots, and boarded-up stores.

“One of my goals is to disrupt the privileged point of view that only educated and elite practitioners can create work about the poor or disenfranchised,” she tells the artist Dawoud Bey in their interview for the book. “My mother did not have to read Roland Barthes to understand death in a photograph.”

LaToya on the subject of her first monograph, “The Notion of Family”

Frazier provides short texts with each image—wistful snippets of memory and anecdote merge with facts and statistics. Illness is nearly a constant. As Laura Wexler points out in an accompanying essay, Braddock’s hospital, which eventually housed the town’s only restaurant and therefore became its de facto meeting place, “is as much or more a fixture in this album and this family than the school, the factory, the library, the market, the taxi stand, the pawnshop, or any other institution.”

Throughout the book, Frazier shows her influences from Depression-era images, such as Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” (1936); Frazier has openly wondered what Florence Owens Thompson, Lange’s subject, might’ve said had she been invited to collaborate in documenting her family’s plight. Self-determination rarely figures in the social documentary tradition, and in many ways Frazier’s work seeks to change this. She defines her photography as a “conceptual documentary” practice speaks to her continued faith in the camera as a vehicle for both social change and aesthetic possibility: beauty, in her work, does not preclude protest any more than education presumes awareness.

https://latoyarubyfrazier.com/work/ – a link to LaToya’s website, with all her different pieces of work.

LaToya’s interview in “So Present So Visible”

This quote from the start of the article really stood out to me, as it describes LaToya’s artistic process which I think is really unique. It is useful for me, studying this photographer to understand her motivations for her project and her creative process behind her images. Understanding the reasons behind LaToya’s photography helps the viewer to understand the social context of her images, and the messages she is trying to show.

This quote from the interview speaks about the narrative and text in her book. I find the fact that she says: “the text functions as an image and the photograph becomes the visual language that creates a tension” very interesting. This is a perspective I haven’t thought of before and will be helpful when constructing my essay. The change of the text as an image and the image of text highlights the important of the social context in LaToya’s work. There are clues in the images, mostly not obvious that lead the reader to the context of the subject of her work – this links to the prejudice and media representation that Frazier talks about in the text of the book, and solidifies her points – “The text functions as an image and the photograph becomes the visual language that creates a tension.”

This quote is an important part of the interview. In this quote, LaToya speaks about the experiences of herself and people in her hometown of prejudice and racism towards their community. She speaks about how the media has portrayed her town and its residents – this has been extremely bias and negative, and through her work she sought to change this narrative: “counter this reality” – the reality presented by the media, and to “ultimately re – imagine and rewrite it myself.” This explains LaToya’s moral standpoint behind her images and the influence issues that affect her have had on her work.

This image is black and white, which creates stark contrast within the image. For example, in the middle of the image has a large amount of black tones. This creates a clear division between the two parts of the image. This could signify a dividing factor in the family which drives the two subjects apart, which could be why LaToya chose this composition. This black-toned area of the photo matches with the black of the t-shirt of the subject to the left, creating a link between these two areas of the photograph. This image clearly uses the rule of thirds which can be seen all parts of the image: in the left the start of the black doorframe, creating the first third, the whole of the black doorframe creating the centre third, and the rest of the image to the right creating the last third. The focal point in this image is the door, which creates a high amount of contrast with the different tones of the white towel. The two subjects looking away from each other and the lack of faces in the image draws further attention to the area of dark space in the middle of the image – The exclusion of faces and the body language of the two subjects could signify tension between the two characters orunsettled feelings. To me, there is a sense of thoughfulness and nostalgia in this image, helped by the presentation of the two subjects but also the aesthetic qualities of the image: the image was shot on film and in black and white which creates a more sentimental image of family to me.