Doug Dubois

Doug DuBois, born in 1960, is an American photographer based in Syracuse, New York. He is an associate professor and department chair of Art Photography at the College of Visual and Performing Arts at Syracuse University. The bulk of DuBois’ photography is portraiture, and he is well known for photographs of intimate familial scenes. He creates re-imagined depictions of domestic spaces anticipated the transformations of family life among a “tidal wave of late-capitalist individualism and aspiration.” DuBois is a recipient of a 2012 Guggenheim Fellowship, and his work is in the collections of MoMA in New York, SFMOMA in San Francisco, LACMA and the Getty in Los Angeles, the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

DuBois was born in Dearborn, Michigan and grew up in the suburban New Jersey community of Far Hills. As a teenager, he began taking photographs with a rangefinder camera he found in his father’s closet. He has a younger sister Lise and a younger brother, the composer R. Luke DuBois, who appear often in his early photographs. In between his undergraduate and graduate educations, his father suffered a near-fatal fall from a commuter train and spent several years convalescing in the home, and DuBois documented this process as a “kind of emotional protection.”

All the days and nights

These family portraits formed the basis of a body of work surrounding his family that would continue for twenty-four years and eventually come to be published by Aperture as a photo book titled All the Days and Nights. The photographs in this series document his changing family: his father’s recovery from his injuries juxtaposed with the descent of his mother, his father’s sole caretaker, into the depths of depression and mental illness, the subsequent dissolution of his parent’s marriage, as well as the maturation of his brother and sister.

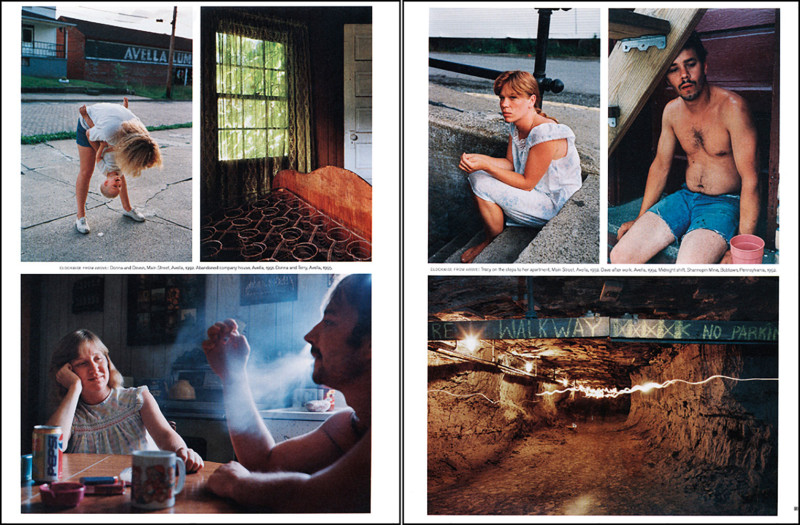

Avella

DuBois’s interest in the family, both his and others, is also evident in a subsequent photo series, “Avella,” which chronicles life in the deindustrialized coal-mining town of Avella, Pennsylvania, where his father grew up. To learn about his family’s hometown DuBois would drive his grandmother around in his aunt’s car while she identified local landmarks and told stories, often taking pictures as they travelled. He documents the decay and blight of the town, but also the families which live in such an environment of insularity and lack of opportunity. The photographs challenge American “myths” surrounding upward economic mobility and question how American families survive amid economic uncertainty.

My last day at seventeen

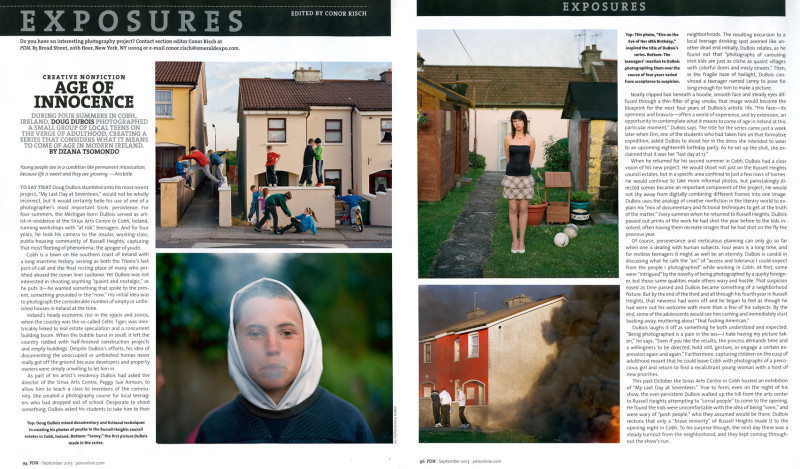

The themes of economic uncertainty and provincial life are likewise central to DuBois’ recent photo series, which was published as the book My Last Day at Seventeen. These photographs depict working-class teenagers in a housing estate in Cobh, County Cork, Ireland after the collapse of the Celtic Tiger economy as a result of the 2008 financial crisis. The series represents the anxiety inherent to the transition from adolescence to adulthood, and how the subjects’ anxiety regarding the future is mirrored by their economic uncertainty. Shot over five summers, the series presents an “endless summer” in which precariously-situated teenagers perform identities informed by an international popular visual culture but mediated through a local context.

“I’m not a social reformer. In shooting these pictures, I had no agenda. They might borrow from the rhetoric of documentary photography, but I’m not a documentary photographer or a photojournalist.” DuBois said that, instead, he found himself “working like a storyteller, creating something that was based in truth.” Sometimes, he explained, “I even gave the kids some direction, like one time when I asked one to jump up on a wall. That’s not journalism.”

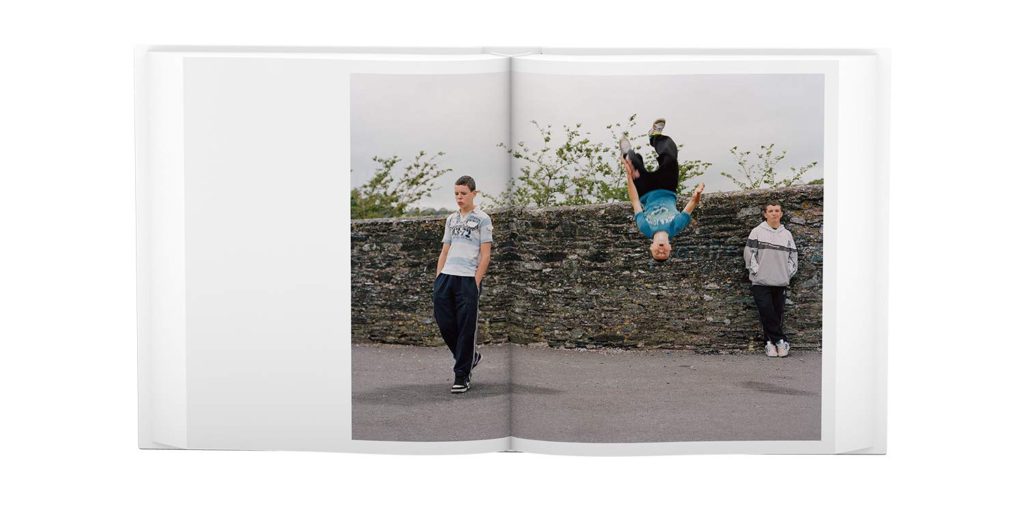

An unexpected component of My Last Day at Seventeen, which appears between various sequences of its colour photos, is a series of brief story vignettes presented in comic-book form. Drawn by the Irish illustrator Patrick Lynch, they feature the recollections of an unidentified narrator who looks back at incidents in his young life against the backdrop of the collective life of the Russell Heights group. Other characters appear, too, including two young women who go to a downtown shop to look at baby carriages. One of them is pregnant, with a baby due soon but without the means, either alone or presumably with the man who fathered her child, to afford the costly pram she covets. On the train back home, the two friends sit in silence, as the pregnant woman rubs her swollen belly.

Similarly, DuBois said that almost as soon as he began getting to know his young subjects, he could sense some complex, overlapping strains of real-life drama that bound many of them and their families together. Inevitably it informed the spirit of his photos. “I wasn’t trying to make a book about Irish youth or even the young people of Cobh or Russell Heights per se,” he explained. “What I created was fiction, a lyrical story set in summer about a moment we all know, when you’re just about to take that first step and become an adult. I’m basking in that moment.” In My Last Day at Seventeen, that moment is at once bittersweet and urgent, languorous and daunting — a slow-moving, time-killing, endless summer, in which, at least until life’s seasons irrevocably change, one can dare to dream of remaining forever young.

DuBois carefully composes his compositions with supplementary lighting and uses either a medium format or a large format folding camera with a cloak. He does not consider his work to be documentary, he views each photo as a collaborative endeavour between artist and subject which is based on truth. DuBois will often stage or recreate photographs, sometimes even alluding to visual works which are not his own, and has borrowed the literary term “creative nonfiction” to describe his work.

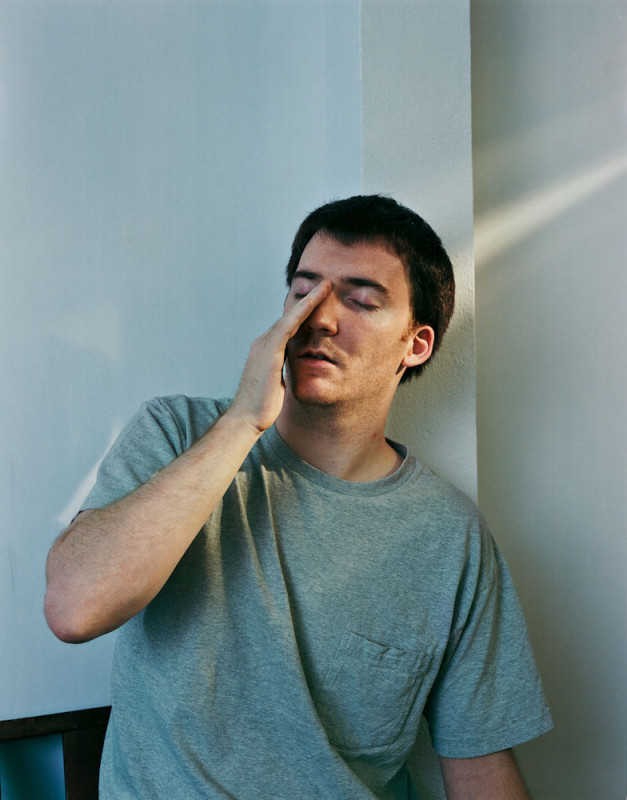

This is one of Doug Dubois’ images from his “Avella” collection. The tones in this image are warm, with orange and green, as well as red as the most vibrant. This image is a little dark, especially in the corners – the top of the image’s corners are the darkest. This darkest around the image creates a natural vignette and makes the subject and white surroundings more vibrant. In my opinion, this image does use the rule of thirds: the subject is situated almost directly in the middle of the image, slightly to the right of the middle third. This helps to create a balanced composition. The windows above the subject also fall perfectly within the middle third, as well as the steps in the bottom middle third. To me, the natural leading lines in this image lead the eye from the bottom corners of the image, up, past the flower pots up the steps and ultimately to the focal point, the subject. There isn’t much noticeable contrast in this image, except for the contrast between the green steps with the white outside of the house. This creates a feeling of separation in the image between the steps, the outside world, and the house. Although subtle, this contrast could relate to the town – after doing some research on the town in which the photos are from in the “Avella” collection, I know that it is a poor, ex-mining town, in the country. The contrast in this image could relate to themes of separation or a feeling of difference from other parts of the area, hinting at the struggle of the population of Avella.

Doug Doubois’ influence on my work

I plan to take inspiration from mainly the “Avella” collection, as it ties in with a style of photography that I like, and it also links to the area which I’m photographing. Although it is not an ex-mining town, Baker and its’ surrounding areas face the same small town, and rural issues, with a similar community outlook and landscape. I think it will be interesting to compare my images taken in Baker with those of Doug Dubois’.

Robert Adams

“I think if you placed me almost anywhere and gave me a camera you could return the next day to find me photographing. It helps me, more than anything I know, to find home.”

Robert Adams

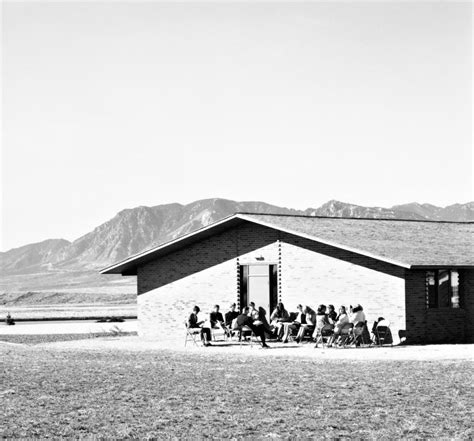

Robert Adams is a photographer who has documented the extent and the limits of our damage to the American West, recording there, in over fifty books of pictures, both reasons to despair and to hope. “The goal,” he has said, “is to face facts but to find a basis for hope. To try for alchemy.” Adams grew up in New Jersey, Wisconsin, and Colorado, in each place enjoying the out-of-doors, often in company with his father.

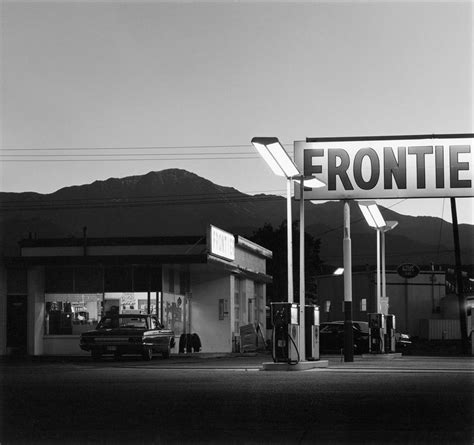

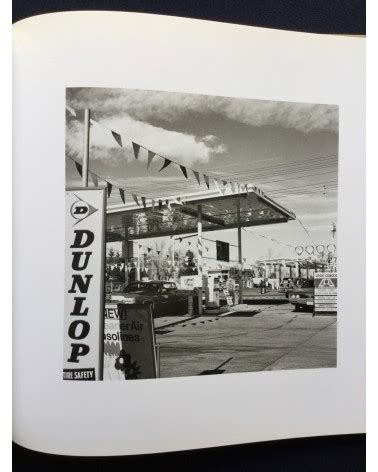

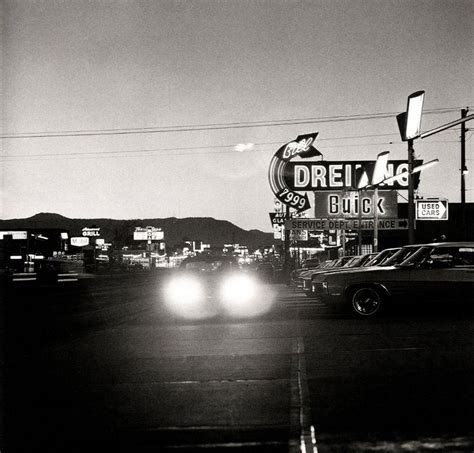

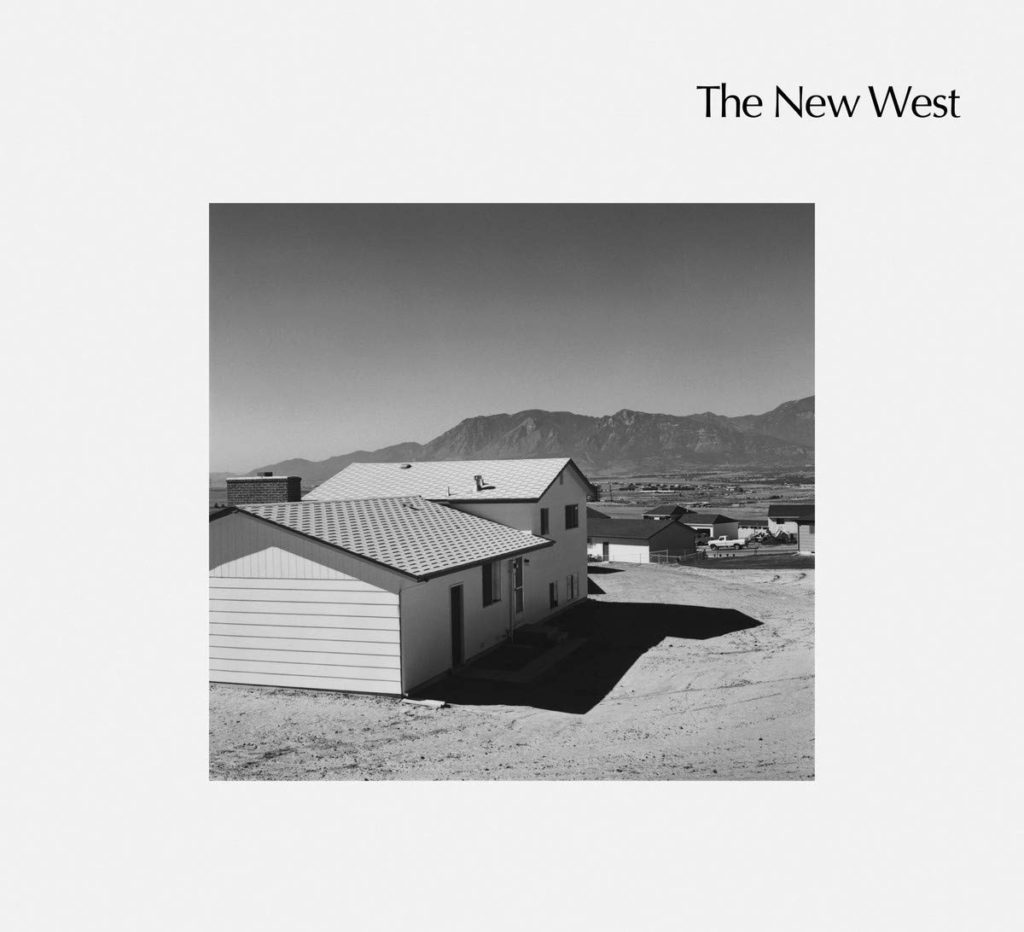

At age twenty-five, as a college English teacher with summers off, he learned photography, choosing as his first subjects early prairie churches and early Hispanic art, subjects of unalloyed beauty. After spending time in Scandinavia with his Swedish wife, Kerstin, however, he realized that there were complexities in American geography that were worth exploring. In the 1970s and ’80s, Adams produced a series of books—The New West, Denver, What We Bought, Summer Nights—that focused on expanding suburbs along Colorado’s Front Range, books that pictured heedless development but also the surviving light, scale, form, and silence of the natural world. He also examined this mixture of humanity’s imprint and nature’s resilience in the wider western landscape (From the Missouri West) and the Los Angeles basin (Los Angeles Spring, California).

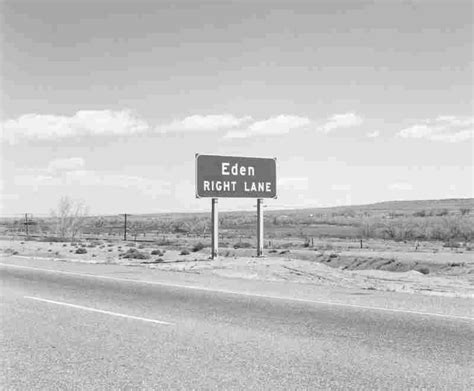

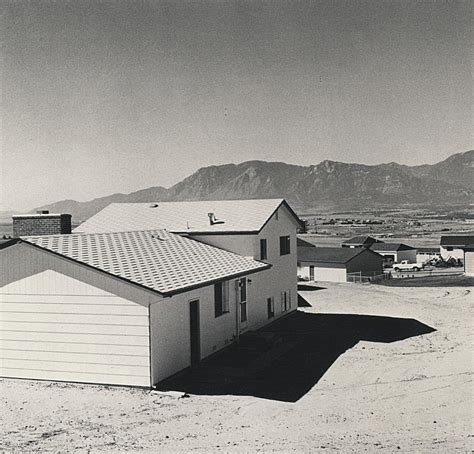

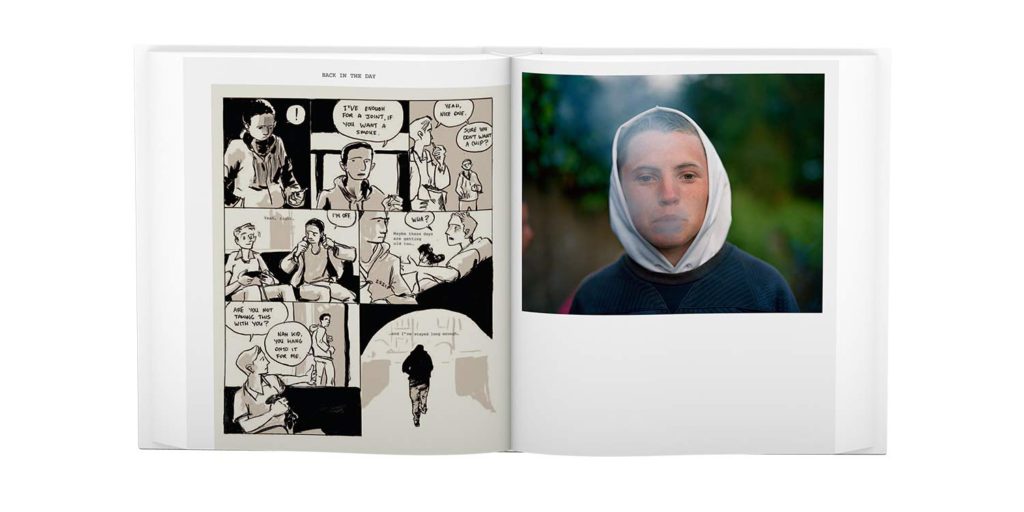

The turning point in Adams’ career was the publication of his highly acclaimed photo essay, The New West, in 1974, which catapulted the image-maker into the public eye. Divided into five sections, the book takes us along the front wall of the Colorado Rocky Mountains, presenting a representative sampling of the entire suburban Southwest. We are first confronted with two, light-drenched images of sprawling prairies, where the only sign of human intervention are electricity pylons and wooden fence posts. Then these open fields are shown bearing signs, first: No Trespassing, then: For Sale or Lease, and you begin to feel the shadow of commercial opportunism ominously approaching. Sure enough, the next section depicts the rapidly growing expanse of tract houses and mobile homes popping up along the Front Range, breaking us in with an image of the foundations of a single tract house being laid in a sparse stretch of land, before presenting us with an entire town of these compact white abodes, which nevertheless appear tiny and somehow insignificant against the backdrop of the towering mountains and an omnipresent sky.

Depicting the unwavering presence and beauty of nature in the face of human intervention was, for Adams, a key element of the project. As he explains in the book’s introduction, “Why open our eyes anywhere but in undamaged places like national parks? One reason is, of course, that we do not live in parks, that we need to improve things at home and to do that we have to see the facts… Paradoxically, however, we also need to see the whole geography, natural and man-made, to experience peace; all land, no matter what has happened to it, has over it a grace, an absolute persistent beauty.” And indeed, even when Adams zooms in on the man-made – be it a woman strikingly silhouetted between two windows of her neat brick bungalow, a packed Denver car park or a peak-side gas station, complete with enormous sign – there is an inherent, inescapable allure, stemming from the photographer’s aptitude for composition and ability to encapsulate the atmospheric quality of light so unique to the area.

Robert Adams’ influence on my work

I chose Robert Adams as one of my photographers to focus on for this project due to similar themes in his work to what I plan on photographing – I plan to photograph the idea of the “new west”. The area in which I’m staying is an old gold mining town, known for its’ wild west – esque elements and I plan to photograph this historical element. Furthermore, Adams captured a lot of prairie land, which is similar to the landscape in my location – I think it will be interesting to capture similar landscapes to his in more recent times to compare and contrast. I want to include a photojournalistic element in my images also. I am going to try and capture living in the town in the modern day, and see if those wild west elements of Baker City are still present today – in this way, I am including history in my images and research, which I like as it helps me inform the ways I plan and execute my photoshoots.