Romanticism emerged after 1789, the year of the French Revolution that caused a relevant social change in Europe. Romanticism, first defined as an aesthetic in literary criticism around 1800, gained momentum as an artistic movement in France and Britain in the early decades of the nineteenth century and flourished until the mid-century. Romanticism spread throughout Europe in the 19th century and developed as an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that embraced various arts such as literature, painting, music and history. Romanticism was also expressed in architecture through the imitation of older architectural styles.

Romanticism was an art form that rejected classicalism and focused on nature, imagination and emotion. Landscape photography was popular at this time, therefore, romantic landscapes were common. The landscapes focused on the beauty of nature and included a lot of running water and vast forests.

Ansel Adams

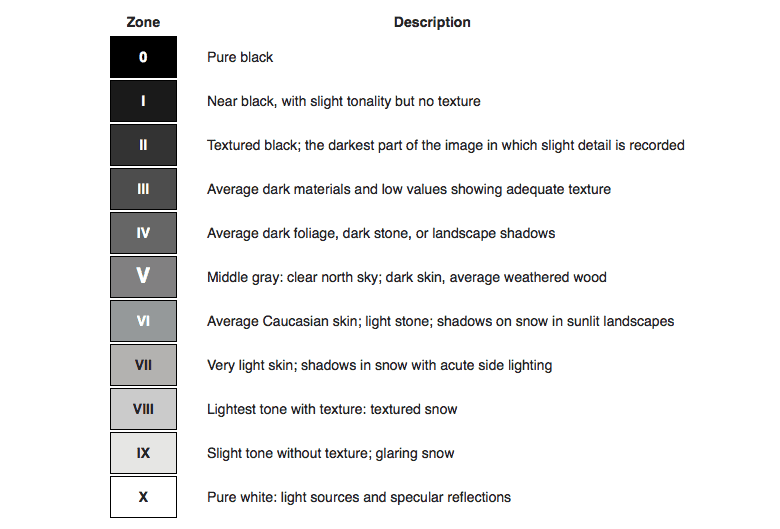

Ansel Easton Adams was an American landscape photographer and environmentalist known for his black-and-white images of the American West. He and Fred Archer developed an exacting system of image-making called the Zone System, a method of achieving a desired final print through a deep technical understanding of how tonal range is recorded and developed during exposure, negative development, and printing. The resulting clarity and depth of such images characterized his photography.

The zone system of Ansel Adams divides the photo into eleven zones; nine shades of grey, together with pure black and pure white. Adams, who photographed in black in the white negative film made sure to expose the darkest parts of his scenery. This way he prevented having pure black in the photo. When developing his photo paper, he made sure to manipulate the dark and light parts in his photo in such a way, that the shades of grey would follow his zone system.

The Zone System is a photographic technique for determining optimal film exposure and development. The Zone System provides photographers with a systematic method of precisely defining the relationship between the way they visualize the photographic subject and the final results. Although it originated with black-and-white sheet film, the Zone System is also applicable to roll film, both black-and-white and colour, negative and reversal and to digital photography.

Adams’s reputation soared in 1931 following his first solo exhibition, featuring sixty of his photographs of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. In 1932, Adams founded Group f/64 with Edward Weston, the group was active between 1932 and 1935, during this time they comprised a group of photographers – including Imogen Cunningham, Willard Van Dyke, Consuelo Kanaga, Henry Swift, Alma Lavenson, and Sonya Noskowiak. The group advocated Straight and unmanipulated photography over pictorialism.

During the early 1930s, Adams wrote for the magazine Camera Craft and published his book Making a Photograph in 1935, in which he demonstrated a technical, but straightforward and approachable way of writing about photography. Making a Photograph was a great success and continued the newly established tradition of the photography manual. The book was illustrated with high-quality reproductions of his photographs, and technical commentary about how to “make” rather than “take” the best photographs.

Don McCullin

Sir Donald McCullin is a British photojournalist, particularly recognised for his war photography and images of urban strife. His career, which began in 1959, has specialised in examining the underside of society, and his photographs have depicted the unemployed, downtrodden and impoverished. McCullin has documented the poverty of London’s East End, the horrors of wars in Africa, Asia or the Middle East. As well as creating pictures of arranged still lives, soulful portraits and moving landscapes.

McCullin was called up for National Service with the RAF. After postings to Egypt, Kenya and Cyprus he returned to London armed with a twin reflex Rolleicord camera and began photographing friends from a local gang named The Guv’nors. McCullin was persuaded to show these to the picture editor at the Observer in 1959, he earned his first commission at age 23 and began his long and distinguished career in photography.

McCullin mainly focused on photographing and writing about the wars and the main events going on around the world, one of his bigger pieces was in 1961 when he won the British Press Award for his essay on the construction of the Berlin Wall. His first taste of war came in Cyprus, in 1964, where he covered the armed eruption of ethnic and nationalistic tension, he initially wrote for the Observer and, from 1966, for The Sunday Times. Away from war Don’s work has often focused on the suffering of the poor and underprivileged and he has produced moving essays on the homeless of London’s East End and the working classes of Britain’s industrialised cities.

From the early 1980s, he focused his foreign adventures on more peaceful matters. He travelled extensively through Indonesia, India and Africa returning with powerful essays on places and people that, in some cases, had few if any previous encounters with the Western world. At home, he has spent three decades chronicling the English countryside – in particular the landscapes of Somerset – and creating meticulously constructed still life’s all to great acclaim. Yet he still feels the lure of war. As recently as October 2015 Don travelled to Kurdistan in northern Iraq to photograph the Kurds’ three-way struggle with ISIS, Syria and Turkey.

Image Analysis

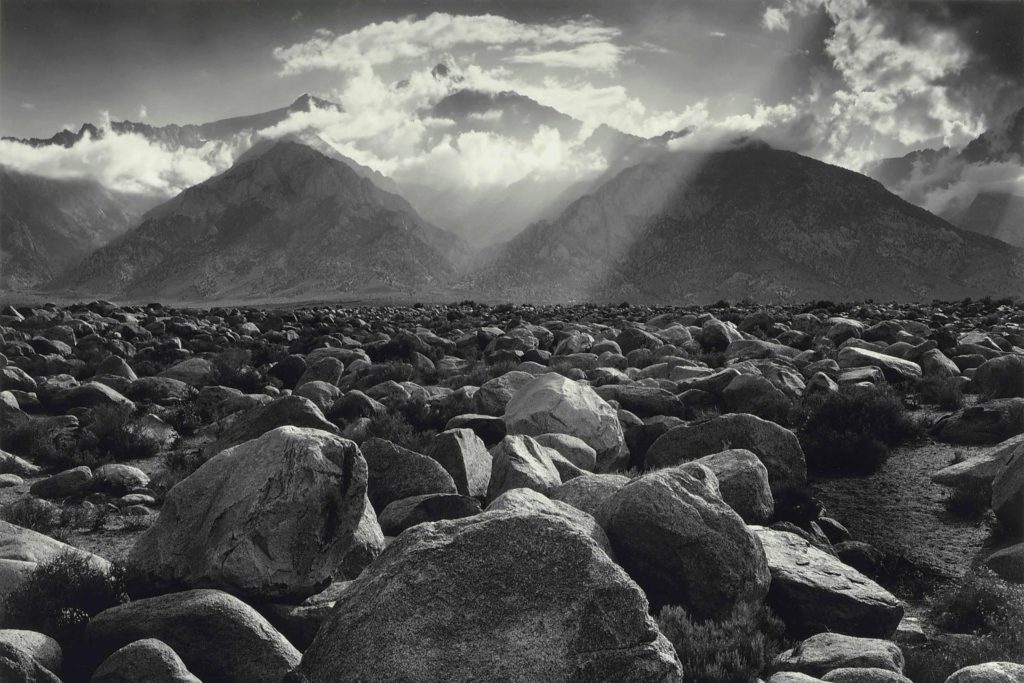

I have chosen this photo because of its harsh light from the sun which looks like a mist covering the mountains. The light sort of resembles a spot like shining on the stage which how you can only see it directly on one spot in the midground. The angle which the photo was taken at makes the pebbles and rocks in the foreground seem bigger than they are. Ansel Adams must have gotten quite close to the ground to take this as the rocks are mostly in focus and they slowly lose that when they get further away. The smaller rocks are also a lot more pigmented than the mounts in the background due to the angle and closeness of the camera. The photo is also a good example of Adam’s zone system, for example, the clouds would probably be placed at a 9 or 10 whereas the spaces in-between the smaller rocks might be put at a 0 or 1 which shows how Ansel captures every different contrasting shade in his photos.