In the earliest days of landscape photography, technical restraints meant that photographers were bound to working with static subjects, due to long exposure times which rendered any movement blurry. This made landscapes and cityscapes prime material for their exposures.

Depicting a man having his shoes shined, the single image took ten minutes to make and just happened to capture the individual, who stood statically, one leg perched on a stool. The shoe shiner working on Paris’ Boulevard du Temple that day had no idea he would make history.

As the technical side of photography developed and cameras became more affordable, almost anyone could become a photographer. Whilst democratizing and diversifying the craft, this also gave form to some form of elitism, as certain artists began to distance themselves from the status quo by creating their own visual movements.

it is hard to trace the exact origin of landscape photography since the very first photograph that we have knowledge of was taken in an urban landscape during 1826 or 1827 by the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce. Then in 1835 the English scientist Henry Fox Talbot came into play with various photography innovations.

Landscape photography was delivering something that only painting was capable of doing until that time – rendering reality in a two-dimensional format.

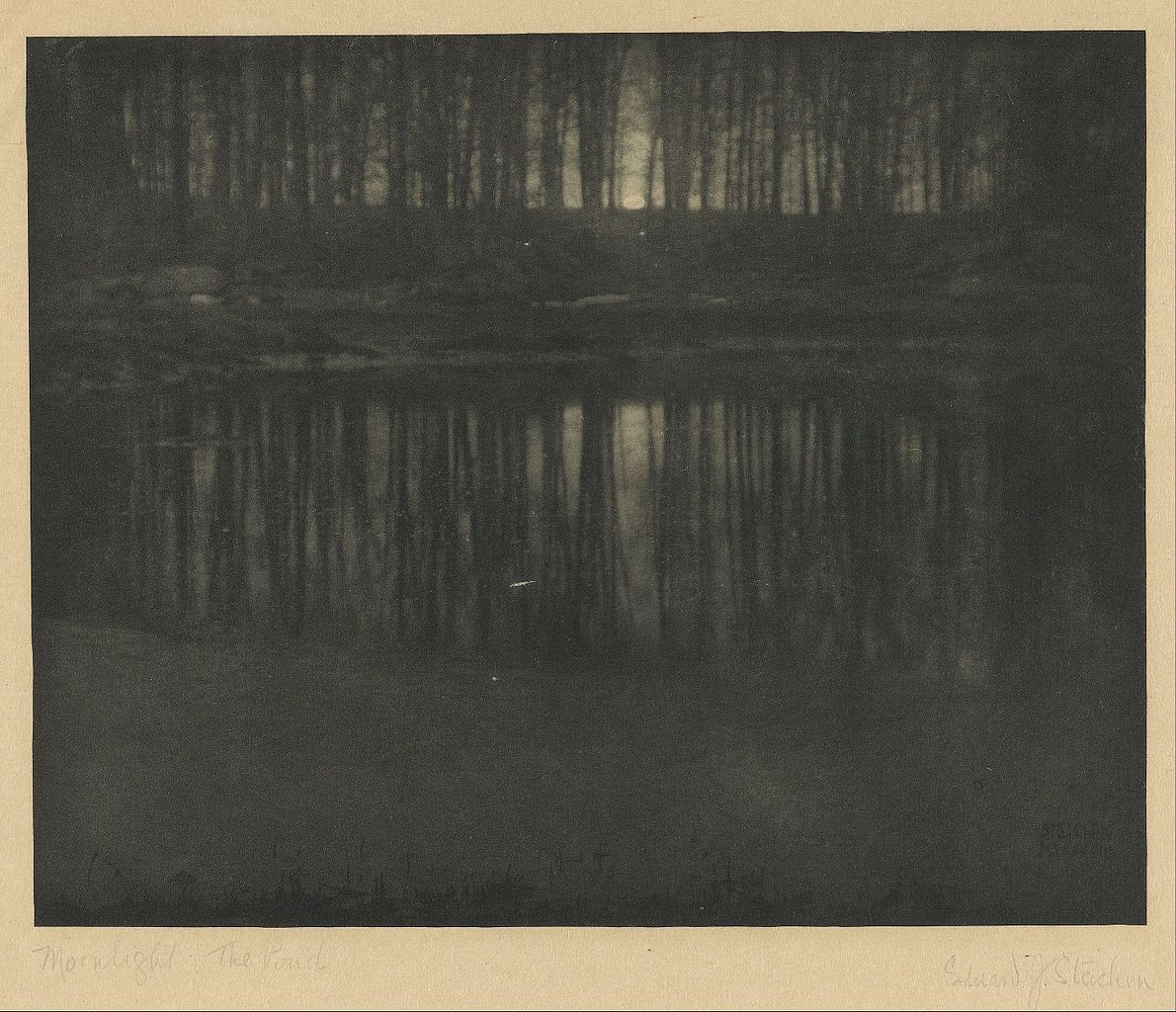

A lot of landscape images and portraits were taken during the Victorian era of photography, but it was in 1904 when Edward Steichen produced a photograph known as Moonlight: The Pond that landscape photography gained certain recognition in the art world.

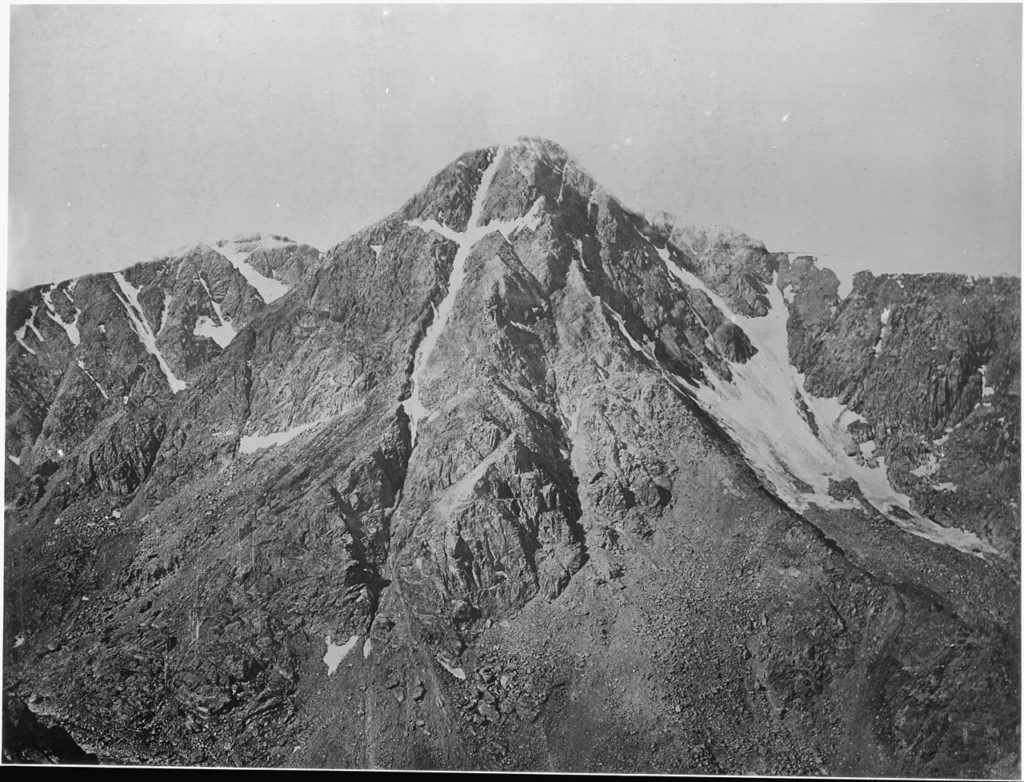

Carleton Watkins is a true pioneer of landscape photography. He is an American photographer who is best known for his amazing photographs of the Yosemite Valley. To capture the extraordinary detail of the breath-taking landscape, Watkins famously packed up his mammoth-plate camera, which used 18X22 inch glass plates, tripods, and tents on mules and trekked through the Valley, returning with 30 mammoth-plate negatives that went on to kick off the National Park movement in the US.

Watkins was also hired by the California State Geological Survey as their official photographer where his team made a large number of photographs that held information about California. The images of Yosemite produced by Watkins were among the first images to be seen of the Yosemite Valley in the Eastern US, caused a stir in the US Congress and these amazing images were, as such, fundamental in convincing the congress and ensuring that Yosemite was preserved as a National Park.

By the time it was announced in 1839, Western industrialized society was ready for photography. The camera’s images appeared and remained viable because they filled cultural and sociological needs that were not being met by pictures created by hand. The photograph was the ultimate response to a social and cultural appetite for a more accurate and real-looking representation of reality, a need that had its origins in the Renaissance.

When the idealized representations of the spiritual universe that inspired the medieval mind no longer served the purposes of increasingly secular societies, their places were taken by paintings and graphic works that portrayed actuality with greater verisimilitude. To render buildings, topography, and figures accurately and in correct proportion, and to suggest objects and figures in spatial relationships as seen by the eye rather than the mind, 15th-century painters devised a system of perspective drawing as well as an optical device called the camera obscura that projected distant scenes onto a flat surface (see A Short Technical History, Part I)—both means remained in use until well into the 19th century.

Realistic depiction in the visual arts was stimulated and assisted also by the climate of scientific inquiry that had emerged in the 16th century and was supported by the middle class during the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th century. Investigations into plant and animal life on the part of anatomists, botanists, and physiologists resulted in a body of knowledge concerning the internal structure as well as superficial appearance of living things, improving artists’ capacity to portray organisms credibly. As physical scientists explored aspects of heat, light, and the solar spectrum, painters became increasingly aware of the visual effects of weather conditions, sunlight and moonlight, atmosphere, and, eventually, the nature of colour itself.

William Henry Jackson is famous for his images from the American West and he was a painter, geological survey photographer and explorer. When Jackson served in the Union Army, he spent most of his free time doing drawings. In 1866, Jackson travelled to the West and along with his brother Edward Jackson, settled down in Omaha and got into the photography business.

Jackson worked for Union Pacific in 1869 where his job was to document sceneries along various railroad routes which were to be used for promotional purpose. Ferdinand Hayden discovered Jackson’s work and asked Jackson to join one of their expeditions to Yellowstone river region.

The next year, Jackson was invited to join the US Government survey of the Yellowstone river and rocky mountains that was led by Ferdinand Hayden. He was also a member of the Hayden Geological survey of 1871 and he along with other members of the expedition documenting the Yellowstone region played an important role in convincing the congress to establish the Yellowstone National Park in March 1872, which was the first national park in the US.

Peter henry Emerson was a British writer and photographer who argued about the purpose and meaning of photography. He argued that photography was a form of art and not something that was done for scientific or technical reasons. Inspired by the naturalistic French paintings, Emerson started to photograph country life as naturalistic photography. He got his first album of photographs published in 1856 called the “Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads.”

Sublime

The sublime evades easy definition. Today the word is used for the most ordinary reasons, for a ‘sublime’ tennis shot or a ‘sublime’ evening. In the history of ideas it has a deeper meaning, pointing to the heights of something truly extraordinary, an ideal that artists have long pursued. Taking inspiration from the rediscovery of the work of the classical author the so-called ‘Pseudo-Longinus’ and from the writings of the philosopher Edmund Burke, British artists and writers on art have explored the problem of the sublime for over four hundred years. In the introductory essay Christine Riding and Nigel Llewellyn trace the relationship between British art and the sublime, discussing ideas and definitions of the sublime used in the Baroque, Romantic, Victorian periods and modern periods. The accompanying piece by Ben Quash considers an intractable problem for Christian art – the notion of a separation between the sublime and the beautiful in God’s creation.

The baroque sublime:

The sublime in art, it has often been suggested, starts with Edmund Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry (1757). Before this, so the conventional narrative goes, the sublime was a notion that applied only to rhetoric. However, the sublime in this period was very much concerned with the potential power of style and composition in the visual arts as much as in language, though it had yet to be applied to nature. In recent years the early history of the concept of the sublime has proved a fertile area for research, with attention focusing on the impact of the writings of an ancient Greek writer known as Pseudo-Longinus, which were first translated into English in 1652.The essays and case studies in this section review this earlier sublime, covering the relationships between writing, rhetoric and art in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

The romantic sublime:

Edmund Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry (1757) connected the sublime with experiences of awe, terror and danger. Burke saw nature as the most sublime object, capable of generating the strongest sensations in its beholders. This Romantic conception of the sublime proved influential for several generations of artists.

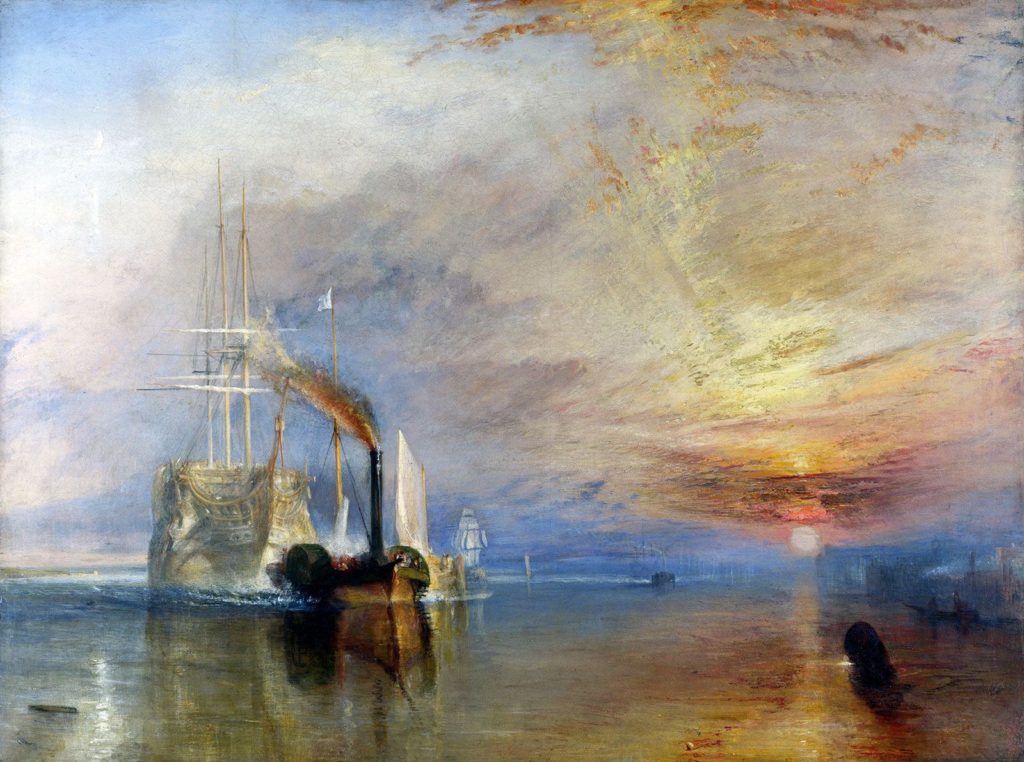

Notions of the sublime are closely linked with the English Romanticism – artists and writers who were concerned with humankind’s relationship to, and reverence for the natural world; in particular those works of painting or poetry that celebrate the majesty and overwhelming power of the natural world. Paintings like Turner’s Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth – with lashing waves and whipping storm clouds, clearly articulate Nature’s majestic and terrifying power. If one witnesses an extreme or terrifying situation and survives, one is then free to experience delight – a ship battling through a violent storm, traversing a precipitous mountain ridge, stumbling through a pitch black forest and finding, at last, a road. The tension between terror and relief is the source of Burke’s sublime feeling – a delight in surviving terror. This is especially the case in art where we become, in a sense, voyeurs of terror; the viewer understands that the terrifying scene they are witnessing is not real and is therefore free to feel a delicious frisson of fear at the idea of being there.

Joseph mallard William turner:

Joseph Mallord William Turner RA, known in his time as William Turner, was an English Romantic painter, printmaker and watercolourist. He is known for his expressive colourisations, imaginative landscapes and turbulent, often violent marine paintings. English artist and a Royal Academician. He is noted for his body of work that depicted the visual proof of the unfolding Industrial Revolution in England. Above all, Turner is known for his loose brushstrokes, vibrant colours, and his subtle rendering of light on landscapes.

Turner effortlessly enjoyed painting various landscapes styles. His art composition incorporated various drawings from all around the world.

Of all Romantic painters influenced by the aesthetic of the sublime, his works have been widely recognised as the most successful in capturing the effect of boundlessness which Burke and Kant saw as a prerequisite for the sublime in verbal and visual representation – the sublime being something that can be evoked but not achieved. Those works by Turner typically seen as sublime employ a formal language that avoids precise definition, instead using paint to hint at the terrifying and awesome but on a relatively modest scale when compared to the bombastic productions of painters such as Francis Danby and James Ward. Through juxtapositions of dark and light, obtrusive facture and subtle blending effects, combined with energetic centrifugal and vortex configurations and exaggerated distortions of scale, Turner’s works have been seen to both elevate and inspire perception in the beholder.

The Victorian sublime

After the Romantic era Victorian artists took a step away from the vastness of the sublime and developed a keener interest in the pursuit of beauty. The following essays and case studies consider why the sublime should have fallen out of favour in this period, and explore the work of those Victorian artists who continued to engage with a sublime aesthetic.

The chief philosopher of the Sublime, Burke in 1757, favoured this aesthetic idea over Beauty because, he said, astonishment, obscurity and vastness cause a more powerful physical reaction in us than Beauty’s orderly calm. Constable’s painting is balanced between these two aesthetic ideas.

RURAL LANDSCAPE

The term “rural landscape” describes the diverse portion of the nation’s land area not densely populated or intensively developed, and not set aside for preservation in a natural state. All kinds of rural land use are involved: agriculture, pastoralism, forestry, wildlife conservation and tourism. Planning also provides guidance in cases of conflict between rural land use and urban or industrial expansion, by indicating which areas of land are most valuable under rural use.

- The cultivated land. It is the space intervened by the work of man, both for cultivation and for forest products, which allocates very little space for the development of infrastructure or public services.

- The reduced public transport. The development of transport services in the rural area is low and low frequency. Its route usually joins the main routes with the nearest villages.

- The low population density. The rural area has few residential areas, and the houses are very far apart. They are mostly inhabited by employees who work in the field.

- The abundant vegetation. A large number of plants, grasslands, and trees are spread throughout the rural territory in a uniform way, naturally or by human intervention.

- The division of the land. The rural area has delimited lands that can be smallholdings (small agricultural properties and not very profitable by type of soil ) or large estates (large properties and very profitable for its nutrient-rich soil).

- The low percentage of environmental pollution. The rural area has a reduced level of carbon dioxide and sulphur dioxide emissions, compared to urban areas that have a high concentration of vehicles and transport.

- Rural tourism. The country houses and the farms are usually a destination requested by people living in the cities, to enjoy the tranquillity and recreation during the seasons or on weekends.

Rural photos

Rural photography refers to photography in the countryside and covers the rural environment. Rural landscapes consist of agriculture. A rural area is an open swath of land that has few homes or other buildings, and not very many people. A rural areas population density is very low. Many people live in a city, or urban area. Their homes and businesses are located very close to one another.