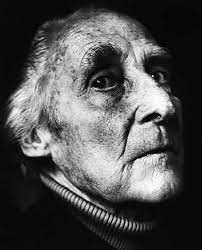

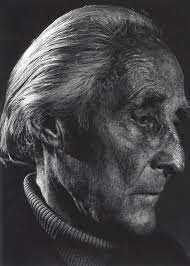

Bill Brandt

Bill Brandt was born in Hamburg on the 2nd of May 1904 to an English father and a German mother. During the 1920s Brandt was sent to a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland, to receive treatment for tuberculosis. It is likely that he took up photography as an amateur enthusiast during this time. In 1927 Brandt travelled to Vienna, where he met the writer and social activist Dr Eugenie Schwarzwald, a pioneer of education for girls in Austria, whose home provided a venue for the intellectual elite of the time. Schwartzwald found a position for Brandt in a local portrait studio and introduced him to the American poet Ezra Pound.

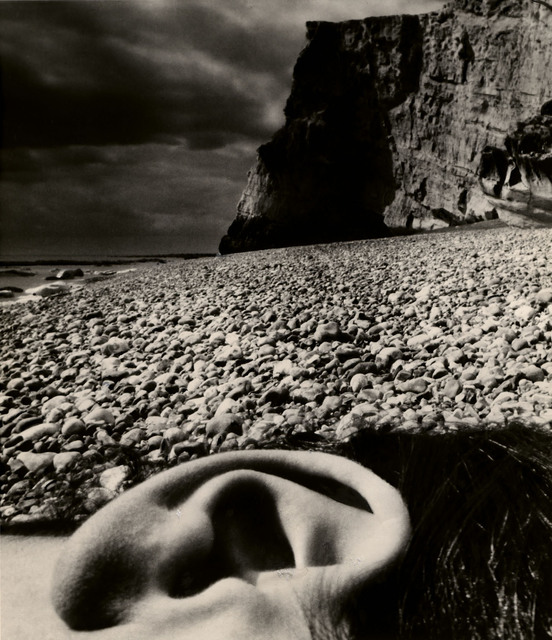

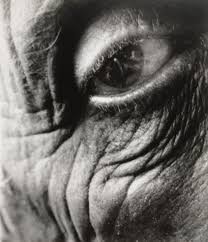

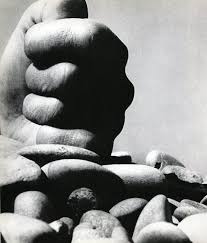

In turn, Pound apparently introduced Brandt to the American surrealist artist Man Ray, who became a major influence on Bill’s work. Brandt Assisted Man Ray in Paris for several months in 1930. Here he witnessed the heyday of surrealist film and grasped the new poetic possibilities of photography. Brandt also learnt several technical processes from Man Ray – the use of extreme grain for graphic effect as well as the use of radical cropping.

In 1932, after a period of travelling around Europe, Brandt married Eva Boros, who he met in Vienna. In 1934 they moved to London and settled in Belsize Park, North London. Brandt adopted Britain as his home and it became the subject of his greatest photographs. In 1936 the first collection of grants early photographs was published in ‘The English at Home.”

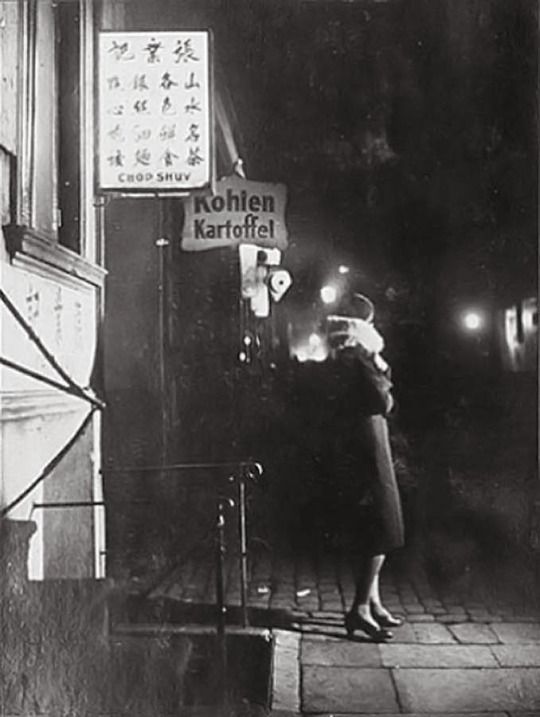

Night photography became one of his specialities, and ‘Woman in Hamburg, St Pauli District’ (1933) may be his earliest experiment in the genre. Brandt posed his wife Eva as a prostitute in the red-light district of Hamburg. Family and friends were to play many roles in his social documentary series. Brandt was also a collage artist, both in photography and later in life. Later in life, Brandt used beach-combed objects in collages. These were published as ‘Bill Brandt: The Assemblages.’

“Woman in Hamburg, St Pauli District”

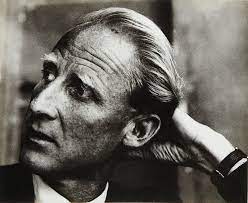

Joachim Schmid

Berlin-based artist Joachim Schmid, who has been concentrating on the recycling of vernacular photographs since the early 1980s, is a living embodiment of the visual scavenger. Schmid studied at Berlin University of the Arts from 1976 to 1981. He began his career as a freelance critic and the publisher of Fotokritik, an iconoclastic and original contribution to West German photography. In the pages of Fotokritik and in his regular articles and lectures for other outlets, Schmid published many examples of his critique of photography as a form of cultural practice.

Living near one of the largest flea markets in Berlin, he had already amassed a rich, deep, and varied collection of vernacular photography which formed the raw material for many of his works. With the advent of the digital age, he has shifted his practice to the Internet, where he continues to ponder the future of photography in a globalized culture. In the current context of the frantic and furious proliferation of images, Schmid aligns himself with fellow artists who seek to tame images and keep them in line.

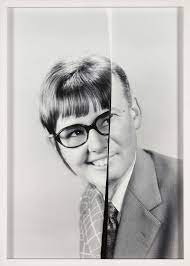

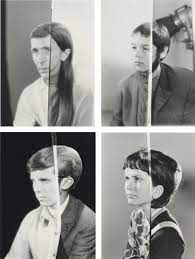

His series Other People’s Photographs (2008–11) takes the form of a set of 96 self-published books, each of which contains a selection of photographs found on the Internet and classified according to specific, nonsensical, odd criteria. Schmid notes that when images lose the thread of their origins, their incontinent production leads us into utter chaos. When this happens, the artist’s mission is to restore order – or at least a possible order, accompanied by a maliciously knowing wink. This provokes confusion in the naive and complicity in connoisseurs capable of savouring a caustic parody of the “official” classificatory methodologies of historians and museums.

Each volume of Other People’s Photographs brings together diverse elements on the basis of some unifying factor – however arbitrary and absurd it may seem – and thus suggests possible ways of categorizing the world. Schmid essentially mocks the supposed coherence of a theory of the catalogue and the archive.

Schmid’s use of extended series reflects his concern with photography as an encompassing, culturally dispersed social and aesthetic feature that runs throughout the public and private spheres of life. The fundamental richness of Schmid’s photographic raw material – along with the wit he often displays – derails any attempt to read his work as pure anthropology or social science. His artistic preoccupations reflect a close observation of photographic history and a fascination with photographic images themselves in all their alternately bizarre and conventionalized aspects.