What were the corn riots about?

During the 18th century, power in Jersey was held in the hands of the Lemprière family. In 1750, Charles Lemprière was made Lieutenant Bailiff, and his brother Philippe was named Receiver-General.

In 1767, people protested about the export of grain from Jersey. Anonymous threats were made against ship owners, a law was passed the following year to keep corn within the island. In august of the same year the court appealed this law, arguing that the levels of corn were plentiful so export was not detrimental. There was suspicion that this appeal was a ploy to raise the price of wheat, which would be beneficial to the rich – many of them had ‘rentes’ owed to them on properties that were payable in wheat. As major landowners, the Lemprière family stood to profit hugely.

The riots

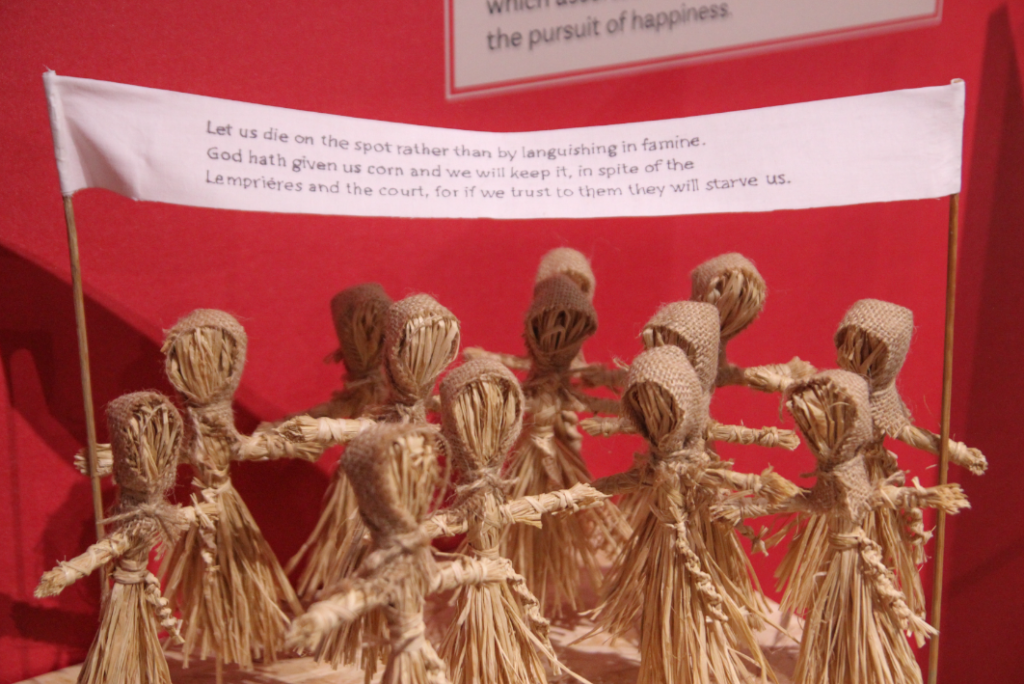

Later in this summer, a ship loaded with corn for exportation was raided by a group of women who demanded that the sailors unload their cargo and sell it in the island – “Let us die on the spot, rather than by languishing in famine, God hath given us corn, and we will keep it, in spite of the Lemprieres, and the court, for if we trust to them they will starve us.”

Then, on the 28th september of the same year, a Court called the Assize d’Héritage was sitting, hearing cases relating to property disputes. The Lieutenant Bailiff, Charles Lemprière, sat as the Head of the Court. Meanwhile, a group of disgruntled individuals from Trinity, St Martin, St John, St Lawrence and St Saviour marched towards Town where their numbers were swelled by residents of St Helier. The group was met at the door of the Royal Court and was urged to disperse and send its demands in a more respectful manner. However, the crowd forced its way into the Court Room armed with clubs and sticks. Inside, they ordered that their demands be written down in the Court book.

The demands of the protestors

That the price of wheat be lowered and set at 20 sols per cabot.

• That foreigners be ejected from the Island.

• That his Majesty’s tithes be reduced to 20 sols per vergée.

• That the value of the liard coin be set to 4 per sol.

• That there should be a limit on the sales tax.

• That seigneurs stop enjoying the practice of champart (the right to every twelfth sheaf of corn or bundle of flax).

• That seigneurs end the right of ‘Jouir des Successions’(the right to enjoy anyone’s estate for a year and a day if they die without heirs).

• That branchage fines could no longer be imposed.

• That Rectors could no longer charge tithes except on apples.

• That charges against Captain Nicholas Fiott be dropped and that he be allowed to return to the Island without an inquiry.

• That the Customs’ House officers be ejected.

After the riots

Following the riots, on 6 October, a meeting of the States of Jersey was held at the Castle when it was agreed that Charles Lemprière, together with two Jurats, and Philippe Lemprière, the Attorney General, would journey to London in order to present their difficulties to the Privy Council, representing the Crown.

At first, the Privy Council was outraged by their reports and commanded that the demands of the rioters be erased from the Court records. On 1 November, a Royal Pardon and a reward of £100 was offered to any rioters who named the ringleaders. After the full situation in the Island became clear, the protestors were eventually pardoned. The corn riots had helped Jersey to become a fairer society at the time, and have an influence on how reform was dealt with from then onwards.

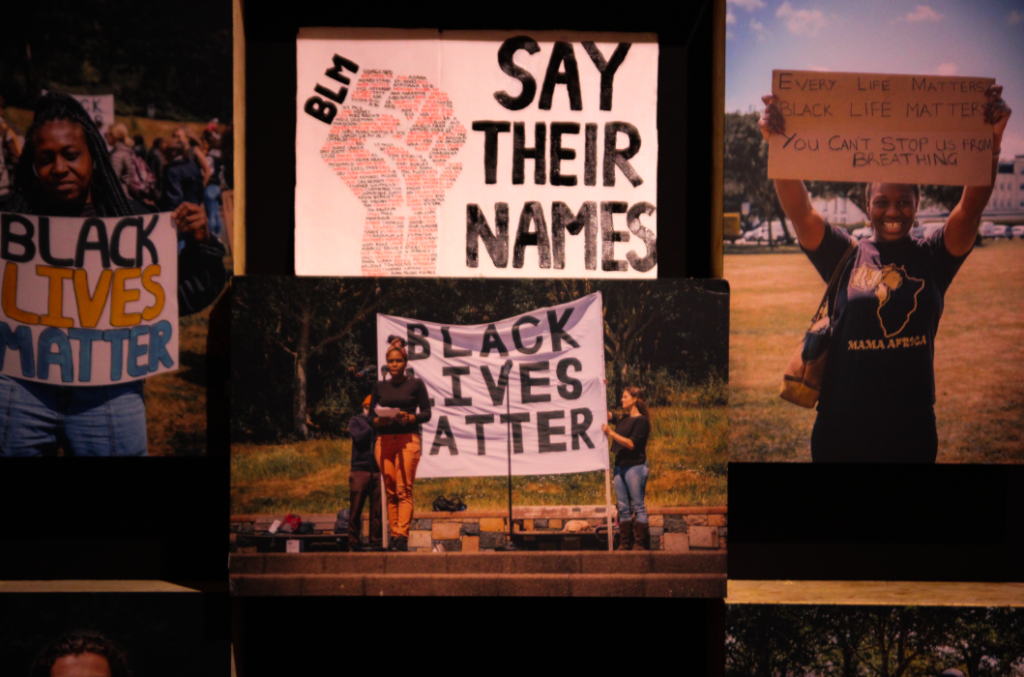

The power of protest in Jersey

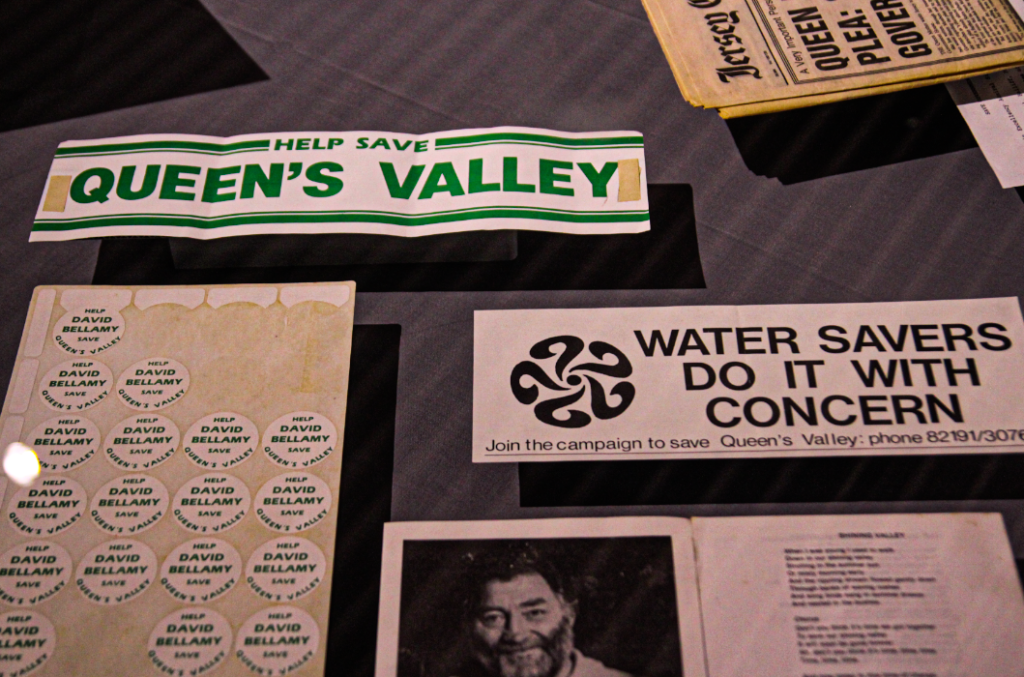

In the 1970s, a growing population and increasing numbers of holiday makers put large pressure on Jersey’s water resources. In 1976, during a summer of droughts and hose pipe bans, the Jersey New Waterworks Company announced plans to flood Queen’s Valley and create a new reservoir. Thousands of islanders supported 2 anti-flooding groups:Concern, Friends of Queen’s Valley, and Save our Valley, arguing flooding the Valley was not a solution. They suggested capping the island’s population at 80,000, installing water meters and using more desalinated water.