The Arab scholar Ibn Al-Haytham (945–1040) is generally credited as being the first person to study how we see; he invented the camera obscura to demonstrate how light can be used to project an image onto a flat surface. Earlier references to the camera obscura have been found in Chinese texts dating to about 400 B.C., and in the writings of Aristotle around 330 B.C. By the mid-1600s, artists began using the camera obscura to help them draw and paint elaborate real-world images with the help of finely crafted lenses. Magic lanterns, the predecessor of the modern projector, also began to appear at this time. Using the same optical principles as the camera obscura, the magic lantern allowed people to project images, usually painted on glass slides, onto large surfaces. They soon became a popular form of mass entertainment.

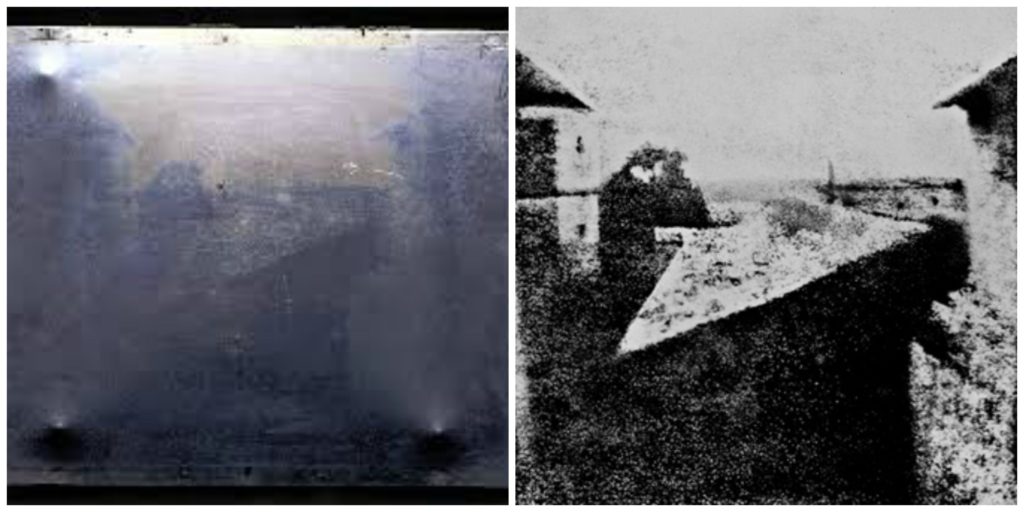

In 1826, French scientist Joseph Nicephore Niepce developed the first photographic image with a camera obscura. Niepce placed an engraving onto a metal plate coated in bitumen and then exposed it to light. The shadowy areas of the engraving blocked light, but the whiter areas permitted light to react with the chemicals on the plate. When Niepce placed the metal plate in a solvent, gradually an image appeared. These heliographs, or sun prints as they were sometimes called, are considered the first photographic images. However, Niepce’s process required eight hours of light exposure to create an image that would soon fade away.

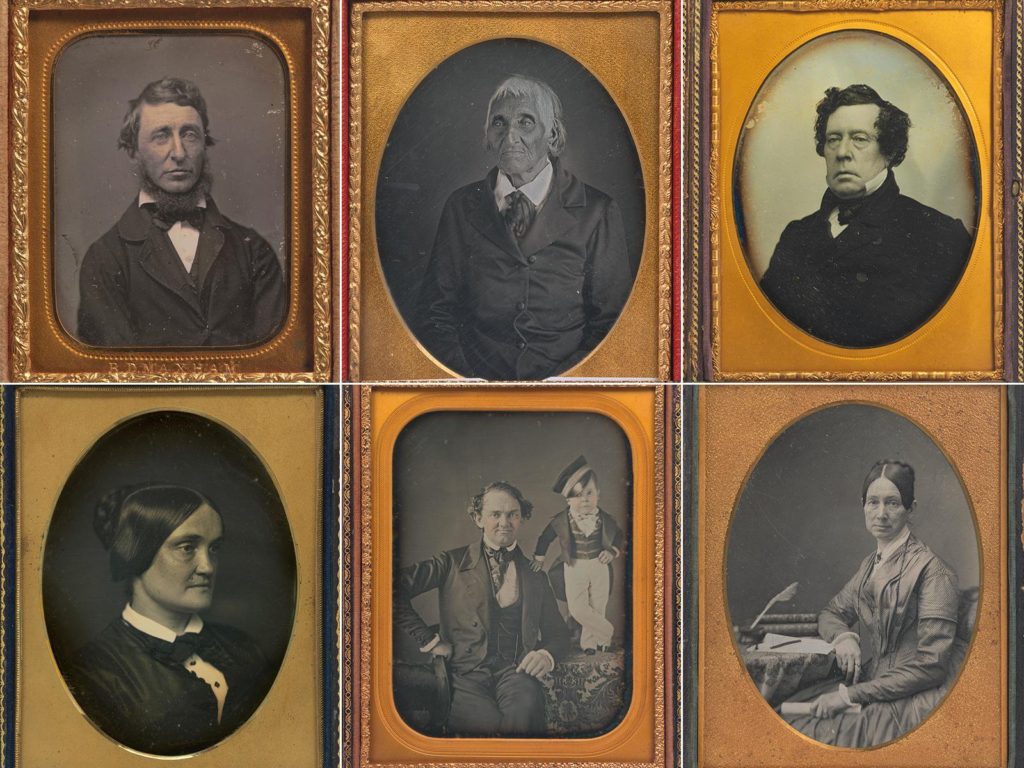

In 1829, Louis Daguerre formed a partnership with Niepce to improve the process Niepce had developed. In 1839, following several years of experimentation and Niepce’s death, Daguerre developed a more convenient and effective method of photography and named it after himself. Daguerre’s daguerreotype process started by fixing the images onto a sheet of silver-plated copper. He then polished the silver and coated it in iodine, creating a surface that was sensitive to light. Then he put the plate in a camera and exposed it for a few minutes. After the image was painted by light, Daguerre bathed the plate in a solution of silver chloride. This process created a lasting image that would not change if exposed to light. The daguerreotype gained popularity quickly in Europe and the U.S. By 1850, there were over 70 daguerreotype studios in New York City alone.

One drawback to daguerreotypes, however, was that they could not be reproduced; each one was a unique image. The ability to create multiple prints came about from the work of Henry Fox Talbot, an English botanist and mathematician. Talbot sensitized paper to light using a silver-salt solution. He then exposed the paper to light. The background became black, and the subject was shown in different shades of grey. This was a negative image. From the paper negative, Talbot made contact prints, reversing the light and shadows to create a detailed picture. In 1841, he perfected this paper-negative process and called it a calotype, Greek for “beautiful picture.”

In 1889, photographer and industrialist George Eastman invented film with a base that was flexible and could be rolled. The 35 mm film most people know today was invented by Kodak in 1913 for the early motion picture industry. In the mid-1920s, the German camera maker Leica used this technology to create the first still camera that used the 35 mm format. The drawback to nitrate-based film was that it was flammable and tended to decay over time. Kodak and other manufacturers began switching to a celluloid base, which was fireproof and more durable. Most films produced up to the 1970s were based on this technology. Since the 1960s, polyester polymers have been used for gelatin-based films.

Having perfected roll film, George Eastman also invented the box-shaped camera that was simple enough for consumers to use. Once the film was used up, the photographer mailed the camera with the film still in it to the Kodak factory, where the film was removed from the camera, processed, and printed. The camera was then reloaded with film and returned. Over the next several decades, major manufacturers such as Kodak in the U.S., Leica in Germany, and Canon and Nikon in Japan would all introduce or develop the major camera formats still in use today. Nikon and Canon would make the interchangeable lens popular and the built-in light meter commonplace.

Apple later introduced its smartphone camera with its first iPhone in 2007, and other companies followed, such as Google and Samsung. By 2013, smartphones with cameras were outselling digital cameras by more than 10-to-1. In 2019, more than 1.5 billion smartphones were sold to consumers, compared with about 550,000 digital cameras over roughly the same period.