All posts by Aimee O

Filters

REVIEWING AND REFLECTING

DESIGNING NEWSPAPER SPREADS

EVALUATION: FILM PRODUCTION

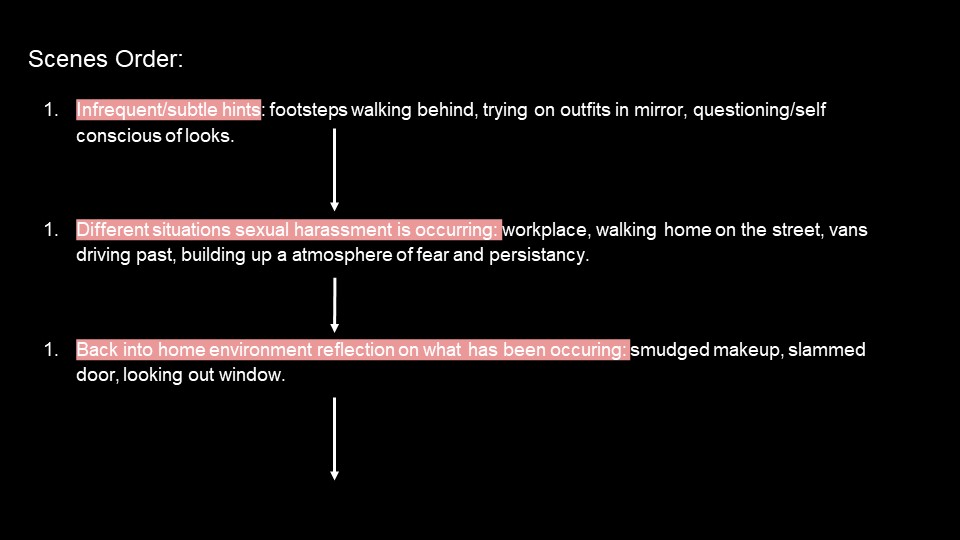

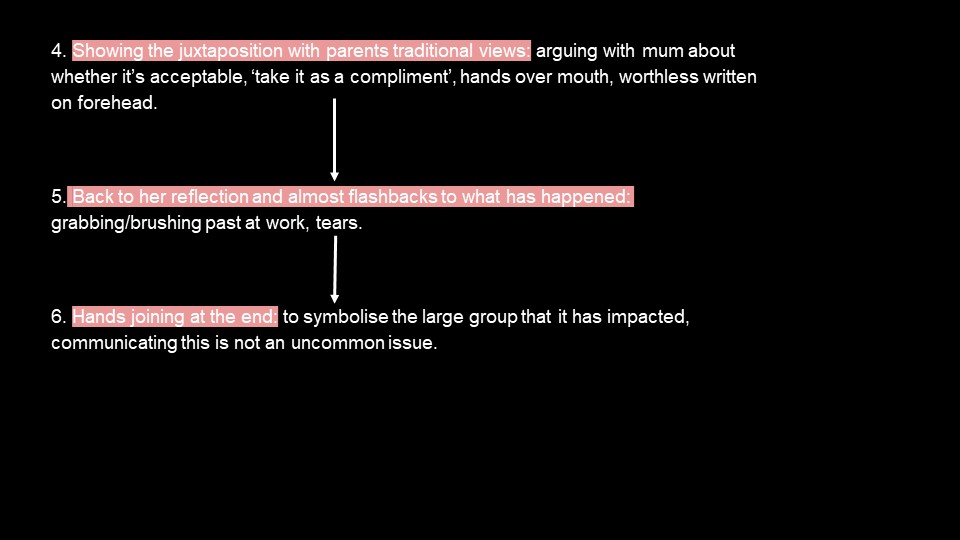

FINAL FILM: UNTIL IT HAPPENS TO YOU

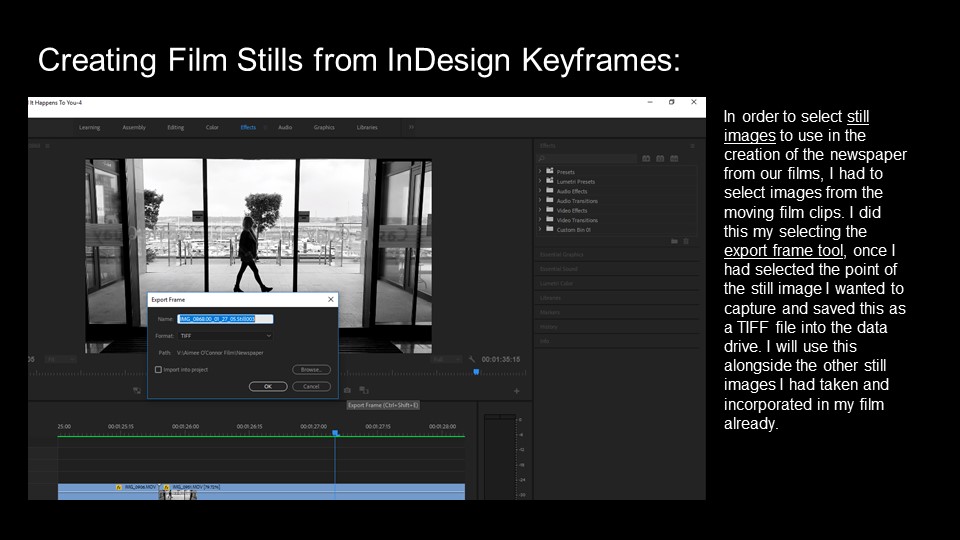

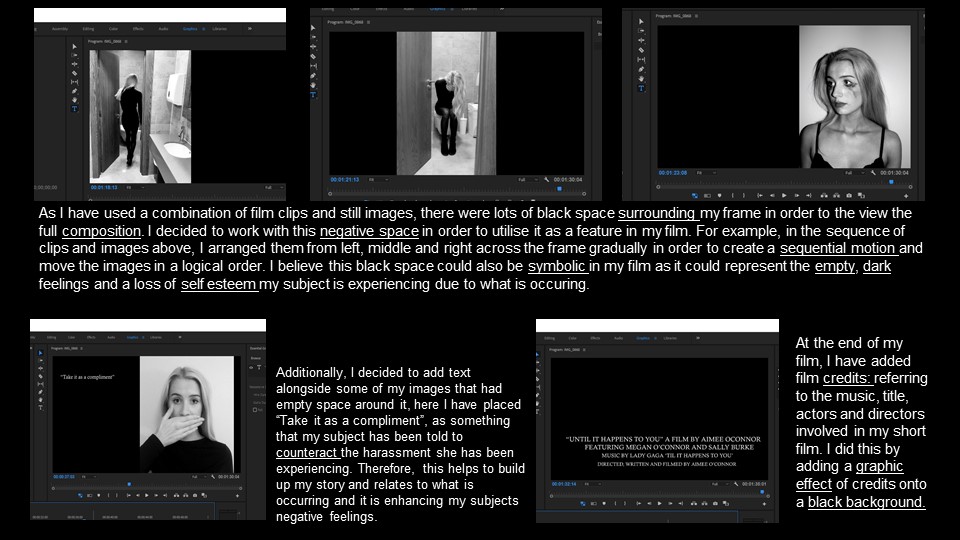

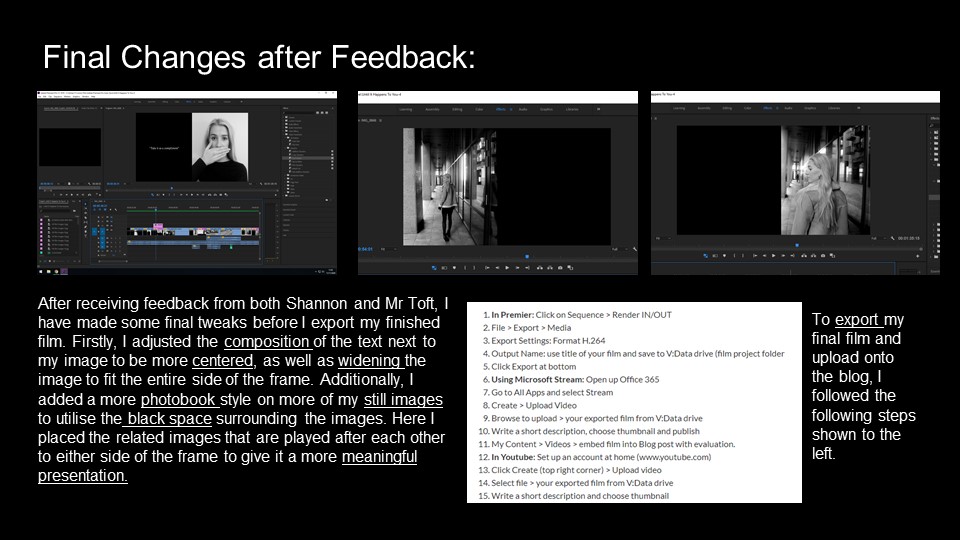

EDITING AND FILM PRODUCTION

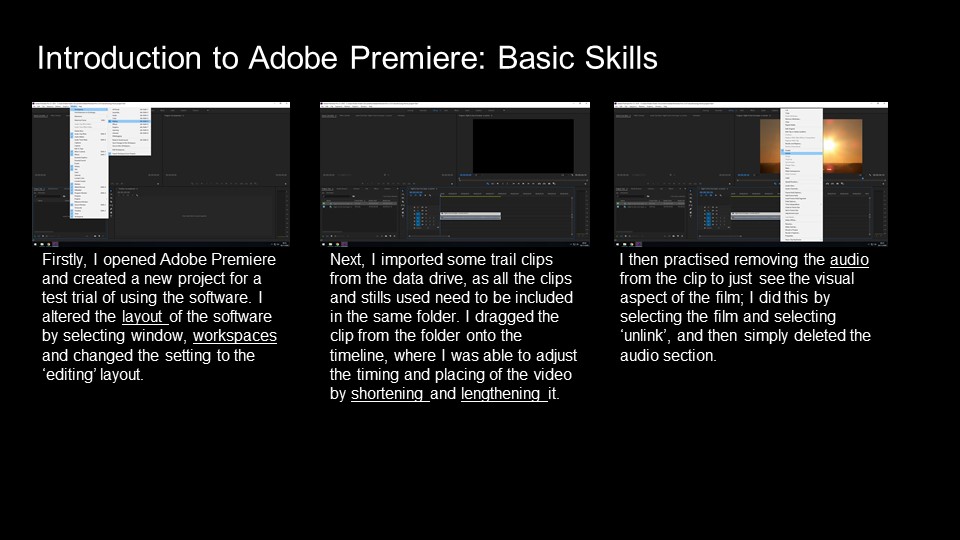

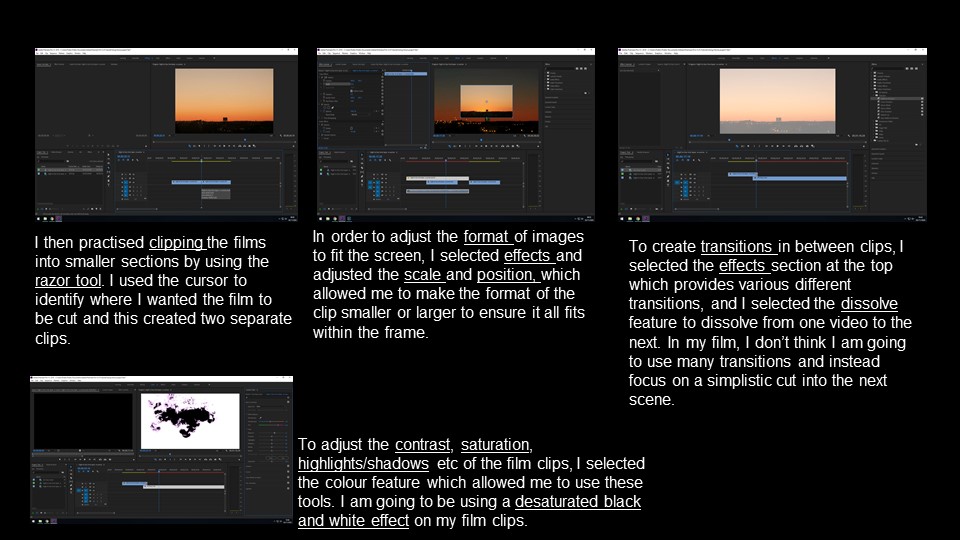

INTRODUCTION TO ADOBE PREMIERE

ESSAY: IN WHAT WAY CAN THE WORK OF CLAUDE CAHUN AND SHANNON O’DONNELL BE CONSIDERED POLTIICAL?

The term political can be described as being interested in or active in politics. Politics is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or of power relations between individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. Claude Cahun and Shannon O’Donnell are both influential photographers who work with self portraits whilst exploring the concepts of gender, identity, equality and incorporate the visual aesthetics of surrealism.

Claude Cahun is remembered for her elaborately staged portraits that were engaging in concepts such as sexuality and gender on both a personal and political level. In a time when surreal artists were mostly men, who portrayed women as erotic and sexual objects; Claude Cahun exemplified the multiple possibilities of identities of women. Cahun’s work can successfully be considered political: she explores all aspects of feminism, identity politics and ideologies surrounding the fluidity of gender before society even realised back in the 1920’s. Her photography challenged gender roles in a society where they were rigidly enforced, being a transgender Jewish lesbian, and anti facist artist, she could be described as bold, rebellious and eye opening. Identity politics is a term that describes a political approach wherein people of a particular gender, religion, race or social background form exclusive socio-political alliances, to support the concerns of particular marginalized groups, in accord with specific social and political changes. I believe that Cahun has contributed towards the demand for identity politics that we now have in our current society, as her work raised issues surrounding women’s equality rights and LGBTQ rights based on her own identity construction.

Cahun described herself as ‘neuter’, putting herself outside the usual categories of gender. Cahun wrote: “Shuffle the cards. Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” She was adamant about eschewing labels and categories. Therefore, this is clearly political as our traditional hierarchical society favoured certain social groups above others in terms of rights to vote, work and to be heard. White males were once seen as the dominant group, on both a gender and racial level. Cahun wanted to break the boundaries of being confined, stereotyped and labelled as being a ‘male’ or ‘female’ due to the stigma attached to these two groups. Men: strong, tough, a fighter, a superhero. Women: powerless, inferior, objectified. I feel that Cahun was fighting for women’s voices, in order to be considered as equals and adopt the typical ‘masculine’ characteristics if they wished to do so. In one of her self portraits, Cahun has shaved her head and she gazes ahead with furious lips, and not at the viewer, to not be consumed as the object. It is a theatrical reminder that identity is a construct, a mask we wear. “Under this mask, another mask,” Cahun wrote. We could even think of her work as a comment on race, as she frequently inverts colours and plays with contrast in one photograph. Her image is duplicated by the mirror next to her – reinforcing the multiplicity of identity, and the roles we play. Additionally, the inclusion of a mirror in art was traditionally used as a convenient way to expose two enticing views of a female subject or, alternatively, as a way to emphasize a woman’s vanity. In this case however, the ‘real’ Cahun looks away from the mirror and rejects being typecast as a passive woman who is visually consumed by admiring herself. There is no sin of vanity at work here, and instead qualities of thoughtfulness, exploration, and self-assurance confront the viewer. As such, Cahun in the mirror, by virtue of the reflection, seems to look away and out of the frame, perhaps feeling a greater freedom in the world of imagination than in everyday society. Cahun explores another aspect of politics through her links to propaganda through her work. In 1937, Cahun escaped to the Isle of Jersey. During the four years of German rule of the Channel Islands, she began a relentless campaign of resistance. She secretly was publishing anti-Nazi propaganda flyers that presented the German campaign as a losing battle. This led to her and her partner Moore, being convicted of undermining the German forces and sentenced to death. Their resistance work reflected their belief that war is “the most drastic regression” from revolution. In a testament written in prison, ” ‘We’ are essentially against nationalisms, separatists, that is against war.” Through this conspiracy, Cahun and Moore continued and extended the political and artistic collaborations they had begun previously. In 1932 both had joined the newly created Association des Ecrivains et Artistes Revolutionnaires, and Cahun had published an anti-Communist pamphlet. Consequently, Cahun is a clear example of an activist and successfully achieved political and social change years beyond her time that she did not live to see.

Similarly, Shannon O’Donnell’s practice explores themes around the gendered experience, with a focus on femininity and masculinity as gendered traits. Her fascination lies with questioning society and challenging traditional views of gender. Her work is informed by her own personal experience and through interviewing specific demographics to help gage a sociological understanding of how gender is viewed or challenged within mainstream society. Cahun is a huge inspiration for O’Donnell being a uprising contemporary photographer, and she often focuses her photographic responses around similar political concepts that Cahun first explored before her time. O’Donnell’s work demonstrates clear links between political movements such as The Suffragettes, Identity Politics, women’s rights and the LGBTQ community.

One of Shannon’s projects, The Cat and The Mouse (2018) has clear political links to the historical context of the Suffragette Movement. A suffragette was a member of an activist women’s organisations in the early 20th century who, under the banner “Votes for Women”, fought for the right to vote in public elections, known as women’s suffrage. The term refers to members of the British Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), a women-only movement founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, which engaged in direct action and civil disobedience. O’Donnell’s work follows the path of Suffragettes and Suffragists around Cardiff in the early 1900s. It encapsulates historically significant places, now forgotten in modern city life. The project also aims to show how the efforts of those Welsh women within the Suffrage movement have allowed for contemporary women of Cardiff, specifically Riverside, the freedom to have a voice, to set up local peaceful organisations for change in the community, as well as a leading example to contemporary activists of today. As she captures images of contemporary key locations, memorable objects, and figures that were involved in the movement, she voices her personal political views and interest in the ideology of women’s rights and feminism. O’Donnell has been engaged in setting up her own activist groups in relation to the concept of identity politics and gender rights throughout her photographic journey. Furthermore, Shrinking Violet (2016) has a clear link to identity politics as she mocks the stereotypes and expectations of women in our once hierarchical society. Shannon focuses on gender in her work and believes that it makes us feel that we need to conform to the expectations placed on us at birth solely on whether we were born male or female. She wanted to create a parody version of the traditional role expected of women from a personal perspective and mimic the tendencies she sees from day to day. Photographing her mother carrying out domestic tasks around the house in unusual poses provides a sarcastic comment on the standards society holds women to. Finally, O’Donnell’s most recent work touches on the political views of the LGBTQ community. That’s Not The Way The River Flows (2019), is a photographic series that playfully explores masculinity and femininity through self-portraits. Shannon states ”This project aims to show the inner conflicts that I have with identity and the gendered experience. It reveals the pressures, stereotypes and difficulties faced with growing up in a heavily gendered society and how that has impacted the acceptance and exploration of the self.” Similar to Cahun, O’Donnell is representing the rights of the LGBTQ community to communicate the demand for acceptance in our society of not identifying as a particular gender, and instead fluctuating to construct an identity to however you please. This has further links to theorists that O’Donnell explores, such as Judith Butler who focuses on gender being a performative act without conscious thought, and therefore enabling it to shift.

In conclusion, I believe that both Cahun and O’Donnell can be seen as considerably politically engaged in their work. They both display clear links to identity politics, focusing on gender as a key concept as they aim to explore the idea that gender is being re-conceptualised, transforming from being solely male and female, to opening to a multitude of subcategories including; gender queer, non-binary, transgender and gender fluid. I believe that Cahun was an extreme activist of her time, due to her risk taking and life threatening actions to make her political views heard. Her fast forward thinking has only been recognised recently as the world has come to understand the concepts of gender fluidity, and therefore I feel that she was very advanced in her actions. O’Donnell emphasises that a political background in her research is what instigates her projects from both a historical and contemporary perspective. However, I believe that O’Donnell may struggle to voice her political opinion in as provoking ways as Cahun did due to the reforms of our society. O’Donnell has to incorporate these concepts into her work in a bold, yet socially acceptable way due to the constraints placed by the Government and laws: which is political in itself. Additionally, O’Donnell being a contemporary photographer is exploring political issues in a very different way: currently, in 2020, there has already been a wider acceptance of identity politics and advancements in women’s rights, LGBTQ rights and the rapid shift towards a more equal society, which Cahun was far from when she was producing her work. Perhaps this could underpin why Cahun had to make her political views evident in such as an iconic and rebellious manner, in order to pave the way to make a change that allows artists such as O’Donnell to continue to explore, as the views of society continue to adapt.