In what way have Jim Goldberg and Ryan McGinley represented youth in their work?

‘Youth’ is described as the period of life in which one is young. It often describes the time between childhood and adulthood where individuals are maturing, filled with vigour, spirit and a sense of freshness. More specifically, ‘youth culture’ refers to how children, adolescents and young adults conduct their lives. It calls attention to the way they express their own identities and demonstrate their sense of belonging to a particular group. The concept behind youth culture states that teenagers are part of a subculture in which the values, rituals, behaviours and norms they share differ from the widely accepted culture of older generations within society. Jim Goldberg and Ryan McGinley explore youth culture towards the end of the 20th century and investigate how modern youth are stereotypically viewed. Goldberg focuses on the lives of derelict children and, specifically, how their behaviour is a result of neglect from their own families and of a failing institutional society. In contrast, McGinley focuses on the reckless experimentation adolescents carry out, not as a result of external influences but rather as a decision to rebel against the governing law. Both photographers, however, explore ways to gain insight into the practices of these individuals in order to dissolve society’s judgement of the youth subculture. In response to McGinley and Goldberg, I have produced a photo-book incorporating the themes of youth and rebellion. The project is a social commentary, showing a rejection of the governing law and of societal standards as a whole. The product explores the freedom of youth and, more specifically, the culture that surrounds myself and one particular social circle.

In her seminal essay Inside/Outside, postmodernist critic Abigail Solomon-Godeau dissects and explores the two different positions that a photographer can take on when photographing their subjects. Firstly, Solomon-Godeau describes Susan Sontag’s view on these roles, where she argued ‘the insider’ as implying a position of ‘…engagement, participation, and privileged knowledge…’ whereas the position of ‘the outsider’ produces an ‘…alienated and voyeuristic relationship…’ between photographer and subject, in turn emphasising the differences between them. Solomon-Godeau refers to Susan Sontag’s criticism of Diane Arbus in her book, On Photography in which she states that the work of Arbus was exploitative and complicit with processes of objectification. Sontag’s criticism raises questions about the morality of the person behind the images, arguing that Arbus is a ‘voyeuristic and deeply morbid connoisseur of the horrible’. However, Solomon-Godeau questions this strict binary established by Sontag and argues how a photographer’s involvement with their subjects might be more complicated. She does so by investigating the relationship between photography and truth.

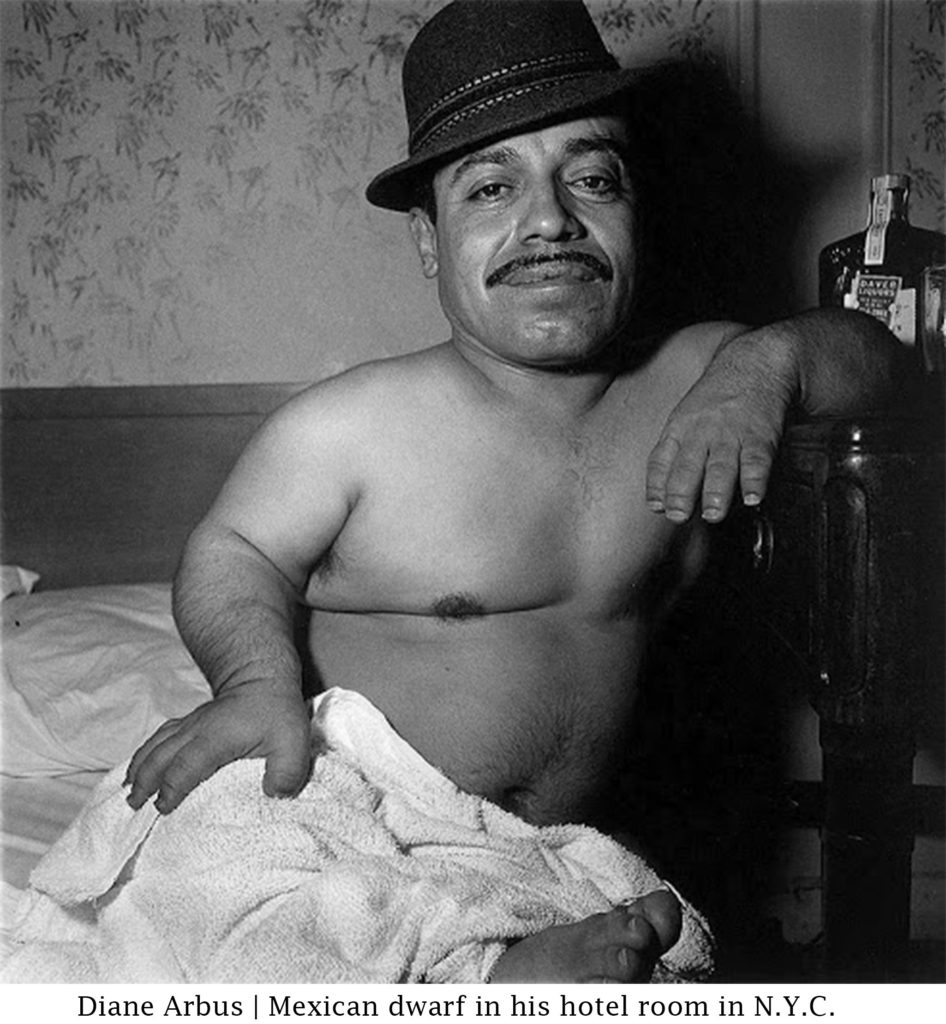

A concern of Solomon-Godeau is how an insider position- in which the photographer lives with and has emotional connection to the subjects- can determine the reception of the images or, still, the nature of the images itself. In regards to Arbus’ photographs, Solomon-Godeau believes it may not have been Arbus’ intent to manifest distate towards marginalized people she’s represented; that- contrary to her intention- Arbus’ subjects became that of objects and spectacles due to the ways of society at the time.

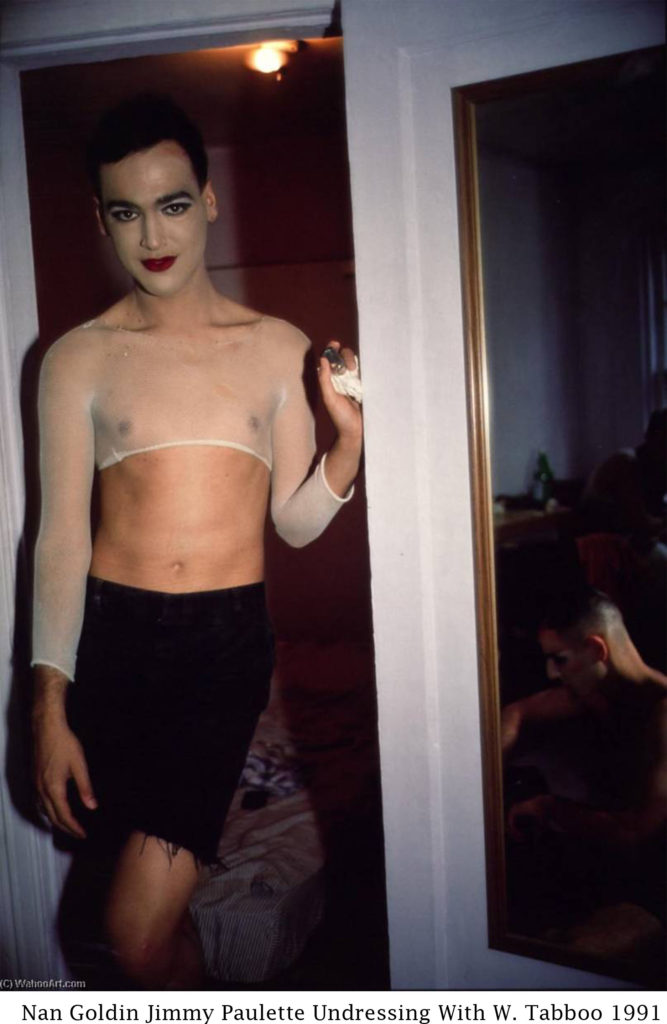

For Solomon-Godeau, Nan Goldin in particular represented the ‘confessional mode’ of privileged knowledge and experience in which the photographer has an inside position and a personal relationship with the subjects presented. Goldin’s work is compared to Diane Arbus as its characters are drawn from the outskirts of society. Often appearing in the images herself, it is clear that Goldin is devoted to and invested in her subjects. However, despite this deeply personal relationship, it’s pondered whether this can alleviate the phobia and contempt manifested towards her subjects by a hetero-normative society. Solomon-Godeau questions whether photographic representation, however sympathetic it may be, can change the views of society towards those considered outside society’s normal standards.

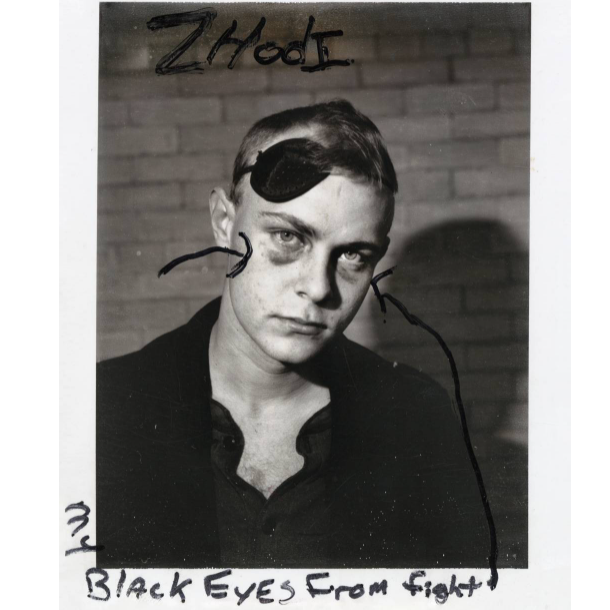

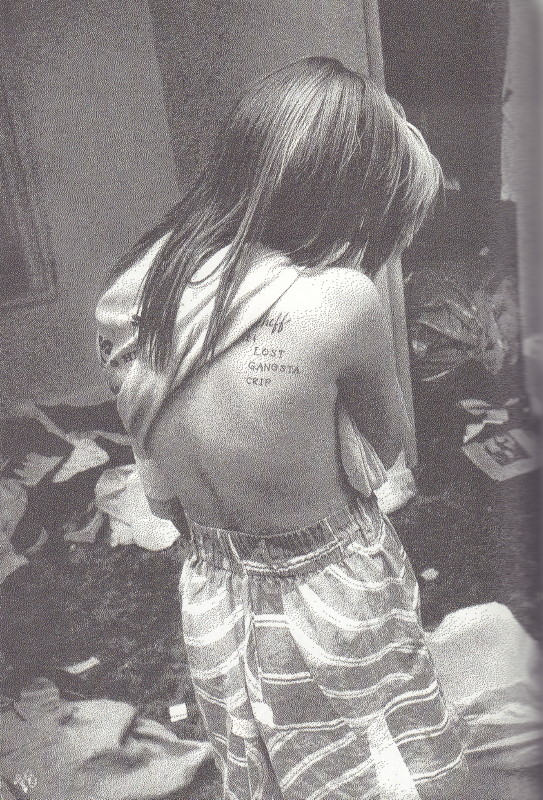

In regards to Raised by Wolves, Sontag may argue that Goldberg takes an outsider’s approach to the subjects within his project. Yet, arguably, Goldberg’s approach differs from Sontag’s assumption in Solomon-Godeau’s eyes. In this case, the assumption that taking an outsider perspective leads to an unsympathetic, objectifying and voyeuristic attitude to those being photographed can be easily rejected. Though he is not pictured, Goldberg’s presence is evident throughout his project and, particularly, in the conversations that take place between himself and his various subjects. The book opens with a double page spreads of what appears to be a grey suburban home, obscured by trees and shaped as though the house is being viewed through binoculars. Almost immediately, an interview between Goldberg and staple character ‘Echo’ is written in text about her backstory and what led her to living in the streets. This instantaneously shows Goldberg’s involvement with the subjects. Similar interviews and anecdotes told by the subjects are present throughout Raised by Wolves. This, in turn, indicates that there isn’t as strict of a binary as mentioned by Sontag referencing a photographer’s position. Despite being an outsider, Goldberg approaches his subjects with sensitivity and empathy, repeatedly allowing for their input throughout. Goldberg gave back to his collaborators (his subjects) by returning photographs to comment on and personalise. The images are sometimes scrawled with text signifying the different identities, challenges, and resilience of the adolescents, and other times capturing a bleak and quiet reality of street life.

Raised by Wolves reveals itself to be a political piece of post-modernistic work. It discloses itself as photographic documentation, social intervention and piece of artwork, additionally incorporating the multitude of approaches made by postmodernist artists such as eclecticism and collaboration. In her book, On Photography, Susan Sontag states that the photographer who photographs a subject cannot intervene in the event occurring, while the photographer who intervenes cannot take the photographs. This pattern within traditional documentary photography states plainly that the photographer should be entirely separated from their subjects’ lives. Goldberg breaks this paradigm in Raised by Wolves by placing himself directly within the narrative. Some argue that the lack of pictures of Goldberg is merely a case of the photographer avoiding interfering with the occurring event, though a stronger argument is that Goldberg’s intervention in the lives of his subject creates a more intimate and sincere reflection of his subjects compared to a photographer who explicitly photographs from outer bounds.

Goldberg presents his subjects, a subculture of neglected and out-casted adolescents, with great delicacy. The narrative focuses on dysfunctional family life in America, about the way teenagers have been led astray, how each one of their rituals is driven by drugs, violence and lack of affection. However, it also highlights love and friendship as a key theme. The compassion Goldberg approached his subjects with revealed and reflected the kindness they showed each other, which is often overlooked and blocked out in the average person’s encounter with the destitute. The narrative is gripping, encouraging the reader to question, rather than to judge the lives of these homeless teens. His in-depth focus on this group of youth has a huge emotional impact on the reader and the political aspect behind Goldberg’s images is present throughout the book. He challenges the generalisations often made about homeless groups in America, in turn posing the reader with questions about the survival of these teenagers, and what their motivation is for survival, considering the bleak reality of their lives. His project aims to question the faults within America’s institutional society that resulted in the troubled lifestyles of these adolescents. As a result, his work presents itself as a highly successful social campaign, attempting to alter the views on vagrant communities and encouraging the current society to approach these groups with sensitivity and to address the failures apparent in society they live in.

Goldberg and Mcginley both take a post-modernist approach to their work. Postmodernism emerged as a response to modernism and a reaction to the age of enlightenment in the late 19th century. Modernism had been based on idealism and an idyllic vision of human life and society. It made the assumption that specific universal truths such as those formed by religion or science could and should be used to understand the nature of our reality. Postmodernism, however, has been built on scepticism and suspicion. It aimed to challenge the idea that there are universal certainties or truths; embracing the complicated and contradictory meanings of images. Postmodernism is focused on the context of its art by making references to things outside of the art work itself such as political, psychological or cultural issues. It focuses on the reception of the artist’s work by their audience.

Regardless of his focus on adolescent lifestyle in America, the work of Ryan McGinley majorly differs from that of Goldberg. In his self-documentary book, The Kids Were Alright, Mcginley captures the outrageous antics and activities of himself, his peers and collaborators, such as street artist Dash Snow, within lower Manhattan through the late 1990s. Taking an insider’s approach, his photographs are that of present and intimate moments, such as those with first boyfriend, as well as moments of exhilaration and introspection. Despite the often mundane setting, McGinley’s images of his youth demonstrate an extensive range of emotions.

McGinley’s approach to his work is similar to Goldberg in the sense that it is mixed with assorted objects and ephemera, such as a set of cameras that he repeatedly threw up upon. In an interview with Autra, McGinley states ‘I would do this project where I would drink Ipecac syrup, the stuff that you give babies if they eat poison berries or something, and it makes them throw up’. This is a clear example of the reckless and absurd behaviour typically associated with youth subcultures. A number of people McGinley drew himself to were considered compulsive and obsessive, many of which died young from AIDS, suicide and drug overdoses. Additionally, McGinley also approached his subjects with a great deal of respect. Having surrounded himself with graffiti writers, McGinley learnt about and presented the paranoia that these artists had. Creating graffiti and vandalising properties was a risky pass-time due to the ‘Grafitti Squad’: a commission established to stop graffiti in New York City. McGinley gained the trust of and photographed the entirety of the IRAK graffiti crew, which had been prioritised by the Graffiti Squad as a group to dismember. He respected these individuals by avoiding their faces and tags whilst they were producing their art. McGinley describes their paranoia as ‘healthy’ and states that he was fascinated by the similarly obsessive and compulsive nature of graffiti, two themes which are present throughout his work.

His post-modernistic approach is present through the collaboration with Dash Snow, an American artist multi-media artist, well-known for his work that embodied a rebellious, drug-fueled lifestyle; one which ultimately led to his demise. In reference to McGinley’s work, Snow stated that “People fall in love with McGinleyʼs work because it tells a story about liberation and hedonism: Where Goldin and Larry Clark were saying something painful and anxiety-producing about kids and what happens when they take drugs and have sex in an ungoverned urban underworld, McGinley started out announcing that ‘The Kids Are Alright,’ fantastic, really, and suggested that a gleeful, unfettered subculture was just around the corner—’still’—if only you knew where to look.”. Similarly to Goldberg, his images show the theme of love and friendship; the intense connection he had with his group at the time. The lifestyle of this particular group of youth separates them from that of a typically normal society, claiming that they slept all day and took advantage of the night, therefore becoming the only people in each others lives.

The work of Ryan McGinley is not in the same political sphere as Jim Goldberg. Whilst Goldberg focuses on how society fails to protect and support children in America and, furthermore, represents the teens that use drugs and carry out illicit activities as a way to escape their past, McGinley presents the thrill-seeking and hedonistic approach him and his friends had during their youth, shooting heroin and carrying out all manners of debauchery in the pursuit of pleasurable experiences. These differences are clear in the nature of their photographs, McGinley’s images are expressive and unrestrained showing the self-indulgence and deviance present in their lives, whereas Goldberg presents the desperation and troubled nature of his subjects. Both, however, are strong examples of post-modernism- giving insight into the varying youth subcultures in America.

In response to Jim Goldberg and Ryan McGinley, the photo-book Passing Youth deals with similar themes of adolescence, hedonism and rebellion. Taking an insider’s approach to the project, the images are an internal reflection upon myself and the people I have surrounded myself with as of late. Incorporating different types of medium, the book is a multifaceted piece of self-documentary. Ephemera within the book include parking notices, polaroids and debit cards, some of which represent the irresponsible and absent-minded nature of modern youth. Passing Youth is similar to that of McGinley’s work as it focuses on my personal life, rather than a whole generation. The images of people within the book have a great deal of significance to me, as well as the locations and personal items throughout the book. My project has a clear personal input, involving myself directly into the narrative through my presence in the images and, additionally, through the use of personally handwritten captions to add context to the images. This aspect allows my project to directly correspond with the work of Jim Goldberg as his collaboration with his subjects produces a similar outcome to my own work.

https://autre.love/interviewsmain/2017/5/20/the-kids-were-alright-an-interview-of-ryan-mcginley

Much improved essay introduction, consider my comments above

Excellently, written essay making mature and intelligent connection between Goldberg and McGinley where appropriate.

Just do another proof reding eg. McGinley (nor Mcginley etc) and add captions underneath illustrations: artists name, title, year

assessment 17/18 = A*

Now you need to match this performance with your photobook. Have you made any new images over h-term?