In what way can the work of Claude Cahun and Shannon O’Donnell be considered political?

Both Claude Cahun and Shannon O’Donnell deal with similar themes of rebellion against society’s expectations and tradition in general, which could both be considered political in a way. They relate to the expectations placed upon women to look and act in a certain way, using self-portraiture to project their own feelings on the subject in a way that others can comprehend and relate. The two artists present the subject of gender, it’s link to biological sex, and their own personal experience in their photography in a way that directly and indirectly challenges both the individual viewer and society as a whole to reflect on gender identity, feminism, and the politics surrounding gender.

The theory that gender, “the roles, characteristics, and activities that distinguish men from women” (MoMA, Constructing Gender) is not some biological fact but rather a series of notions constructed by society, is apparent throughout much of both artists’ work, with the differences being that O’Donnell uses it to explore and experiment with her gender identity, and Cahun is much more continual and secure in representing herself as always on the line between society’s idea of a woman or a man, firmly placing herself on the spectrum of androgyny, instead of simply experimenting with it like O’Donnell. The idea of gender being a social construct link into the Surrealist art movement as well, which Claude Cahun was a key part of during her lifetime.

The link between gender identity and political rebellion is not a new one, as can clearly be seen in Cahun’s work, which dates over sixty years ago in some instances. The connection rises from the continued control of women in the law, from abortion and sexual health nowadays to the right to get married, own property, have a job in any particular career, all of which were limited to women in Cahun’s era, although they would be considered basic rights in modern times. This historic oppression and attempted control of women leads to rebellion from women and men alike, often resorting to art or literature as mediums to express their anger. The use of art as a form of rebellion against politics is one of a few clear reasons why both of these artists and their work can be considered political.

Claude Cahun’s work specifically has key links to the theme of rebellion (both political and societal), gender roles, and the concept of self-expression through clothes and other outward factors. She was a French, queer, Surrealist and Absurdist photographer born to a Jewish family and was active from the 1920s through to the 40s. During the Second World War she was residing in Jersey with her partner Marcel Moore, and while the island was occupied, they both became key resistance fighters against the Nazis. They weren’t originally seen as targets to be feared by the occupants due to their age and the fact they were women, which helped them elude punishment for years while they published and spread anti-Nazi propaganda, often mocking officers and higher-ranking Nazis, criticised fascism, attempted to incite soldiers into rebellion or desertion, and spread news they had heard (illegally) from the BBC. Eventually, they were both arrested and sentenced to death, but were held in prison and released when the island was liberated in 1945.

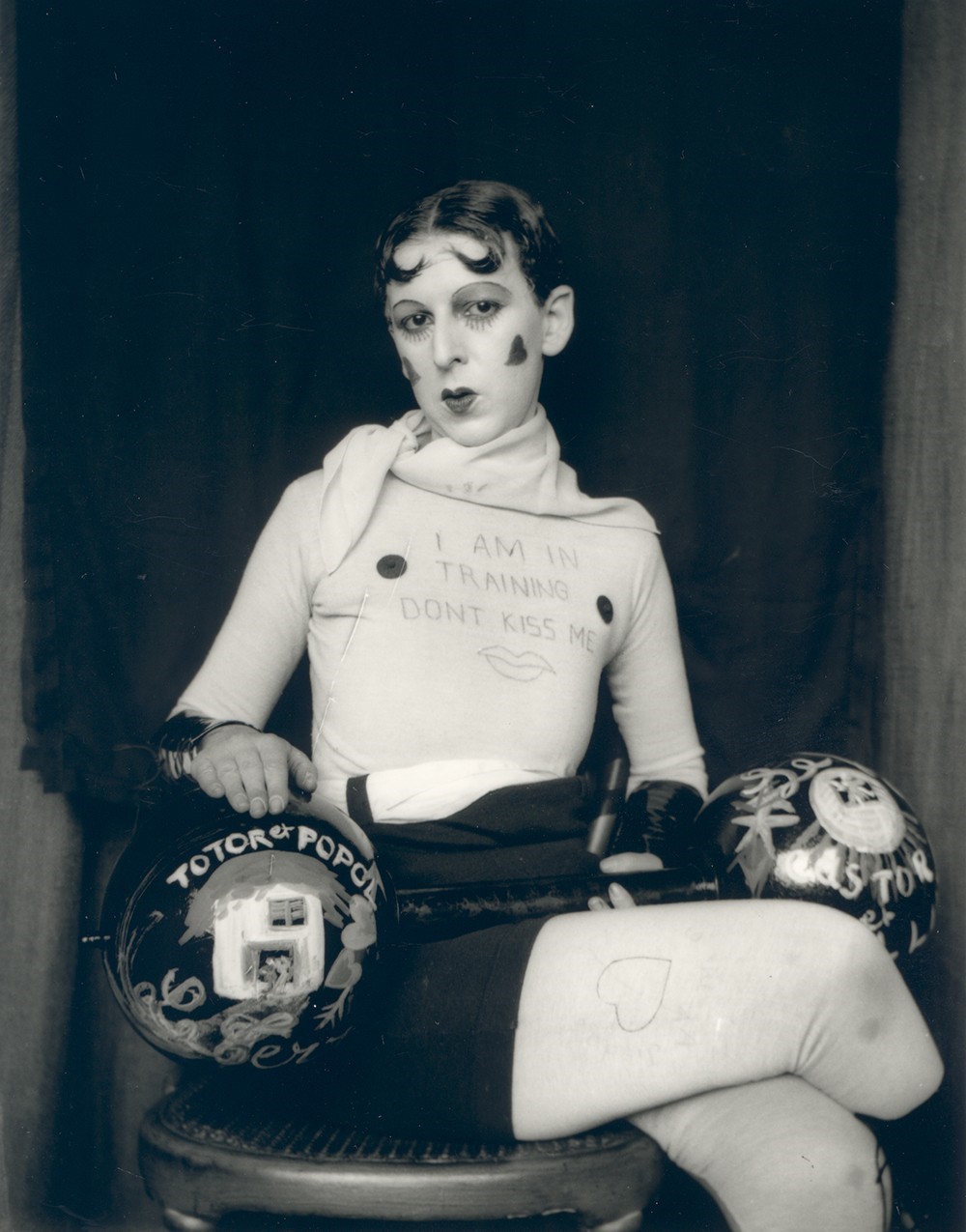

This image represents Cahun’s belief that she had multiple identities at once, famously quoted saying “I will never finish removing all these masks,” demonstrating how her gender was more of a performance than a set of rules she adhered to that were presented to her by other people/society. Her skin is clear and bright white due to the exposure, as a result her dark eyes stand out prominently from the whole image, inviting us to judge her expression and guess her thoughts through them. She was very fond of the double exposure method and often used it in her self-portraits to illustrate two separate identities, or “selfs”, sometimes with completely contrasting characteristics of emotions.

However, in this image, the double exposure is more used to demonstrate how she feels herself pulled between two different sides of herself, perhaps between genders. She said in Disavowed Confessions, “Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.”, which is possibly what this image is visually representing.

“Que me veux tu?”

The image is black and white, typical of the time it was taken (1920s). The focus of the image is clearly the two heads of Cahun in the centre foreground, with a plain dark background drawing even more attention to them. The image is titled “what do you want from me?” in French, which further reveals how Cahun is indifferent to the expectations placed on her by other people to be traditionally feminine, and that her art is a direct rebuttal and refusal of this. Another interpretation could be that the question is directed to herself, and she is internally struggling with how to define herself as a person and be content with it.

part of the “Shrinking Violets” series

Shannon O’Donnell is a contemporary photographer who also focuses on gender roles as topic of exploration, and her work often questions authority figures and prescribed ideas in society. Her series “Shrinking Violets” mocks women’s traditional roles in the household, “Abort Mission” links the Catholic Church to the continued control over women’s reproductive rights and the general oversexualisation of women, and “That’s Not The Way The River Flows” illustrates O’Donnell’s own exploration of her gender identity and traditional ideas of gender in society.

This image is taken from O’Donnell’s project “That’s Not The Way The River Flows,” and it mirrors the image I analysed by Cahun in that it is a self-portrait of her face, representing her internal struggle and her perception of her own identity. She is dressed in a suit, which is stereotypically masculine, but we can see her feminine facial features through the fabric wrapped around her head. This piece of fabric could be interpreted to symbolise how she feels trapped by the societal norms she is expected to follow, or possibly it could be that she feels, much like Cahun, that she is wearing a mask and that the way she presents herself normally is not the way she wants to be.

The image is also in black and white, but less harsh than Cahun’s as the technology nowadays allows for far more tonal range. There are a lot of grey tones in the image, and the fabric covering O’Donnell’s face is practically the same colour as the background; it could almost fade into the background if it weren’t for the fact that O’Donnell’s eyes, eyebrows and lips are still visible underneath. The greatest contrast is between the blazer and the white shirt, as the shirt is quite noticeably brighter white, plus the textures of the two fabrics are visually different: the shirt is smooth, crisp and soft, and the blazer looks rougher and more coarse.

In conclusion, both artists use their gender identity and self-expression to project their rebellion against authority figures, which is in its own way a political statement. In Claude Cahun’s era, the images she created would be a good deal more political and rebellious than O’Donnell’s work is now, due to the growth in acceptance of different gender expressions nowadays and the increase of LGBTQ+ rights, however they are both making a statement in opposition to some form of authority figure. The historic oppression of people expressing themselves freely, particularly queer people like Cahun, has led to these sorts of statements and artworks being inherently linked to politics.

LINKS TO SOURCES USED-

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/296276

- https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/investigating-identity/constructing-gender/

- https://www.npg.org.uk/blog/claude-cahun-freedom-fighter

- https://hautlieucreative.co.uk/photo17a2e/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2017/03/Jones_Eternal-Return.pdf

- https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/dada-and-surrealism/xdc974a79:surrealism/a/surrealism-and-women

- https://www.jerseyheritage.org/media/PDF-Heritage-Mag/Sans%20Nom%20Claude%20Cahun%20%20Marcel%20Moore.pdf

Overall an excellent essay providing intelligent and intellectual references to the many way that the work of both Cahun and O’Donnell’s work can considered to be political and rebellious, performing gender roles for the camera, political activism. Excellent use of quotes to support your own argumentation too making it critical and relevant. Use Harvard system of referencing for the future (we’ll go through later in class)

Marks: 16/18 = A/A*