In what way does the work of Francesca Woodman explore the concepts of femininity and sexuality ?

“Woodman’s photographs show a subject poised between presence and absence, where the body seems to hesitate in its visibility and identity.”

Townsend C, 2006, “Francesca Woodman: Scattered in Space and Time“

INTRODUCTION-

The concept of femininity, its definitions and boundaries, has been explored thousands of times by multitudes of photographers, artists, philosophers and writers, female or not. It changes again and again with each individual interpretation and cultural movement, with the waves of feminism, and with the passing of artistic and cultural movements. The idea that there is an inherent essence to being female has been examined in depth by many artists, writers, philosophers and linguists, including by Judith Butler, whose work “Gender Trouble” revolutionised the way femininity and gender in general is thought of and discussed academically, as well as having a massive impact on the LGBTQ+ community, where gender and sexuality are often seen as fundamentally intertwined and are often questioned and analysed. These notions can all be seen to be represented in, an influence on, or interpreted in Francesca Woodman’s work in some way. From her depiction of her own femininity and sexuality, I believe that Woodman’s work is exceptional in portraying how she views these concepts in a way that is not only original but also has links to other artistic and cultural movements. In this essay I will explore how she connects her personal experience with other photographers’ work and her understanding of the photographic and artistic scene surrounding her work. I will provide an in-depth analysis of her work and discuss how it illustrates her experience with her own femininity. I will explain how she explores her sexuality look at contextual factors and other links to cultural and artistic movements, artists and themes.

THEORETICAL CONTEXT-

Women in the world of art and cinema have continually been portrayed, mainly by men, as sexual objects; their purpose being for exhibition only. Laura Mulvey puts it simply, “in their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed” (Mulvey 1975:19) which accurately explains the persistent representation of the female body as an object of desire first and foremost, both for the artist and characters within the artwork or film as well as the spectator. This perception of women as sexual objects can be linked to many traditional social attitudes regarding gender roles and can be argued to be the base of modern rape culture. However, this connection between a person’s sex and their gender has been furiously debated for decades and probably longer, possibly most notably by Judith Butler in her iconic and transformative book “Gender Trouble”. Her main points can be summarised as this: gender is a socially constructed performance, people’s gender identities are often far more complex than society expects, and the fact that women are socialised to fit within a set of defined “feminine” characteristics. In simple terms, “sex is not the biological meaning of gender and is socially constructed by norms, just as gender is an ongoing performance” (Marilou Niedda, 2020;1). Butler theorises that there is a clear disconnect between a person’s biological sex and their gender, meaning androgyny is a completely valid and understood form of gender expression. Androgyny in photography is used by many artists, often female ones, to distance themselves from the over-sexualised images of women which are seemingly everywhere in art and film, to show themselves as artists breaking barriers, and to represent women in general as more than just erotic objects.

I am in training, don’t kiss me (Claude Cahun, 1927)

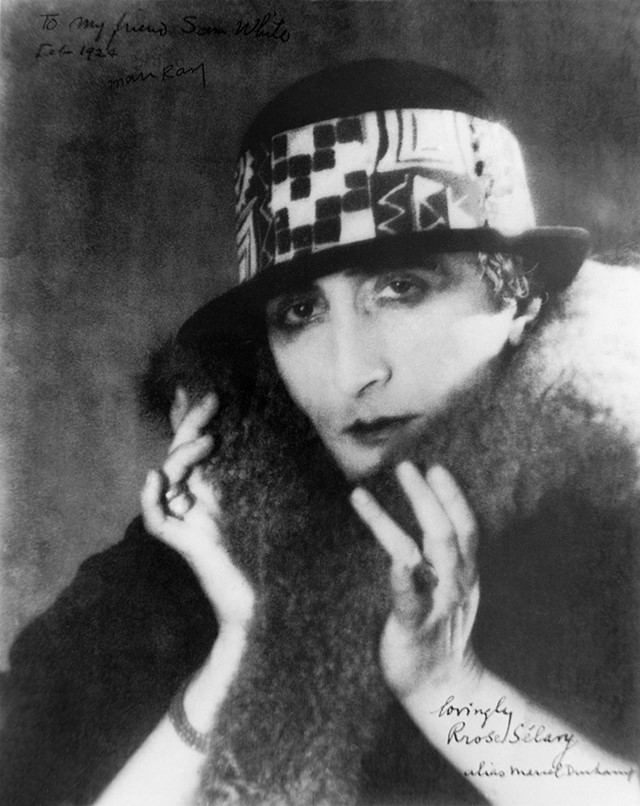

Rrose Selavy (Marcel Duchamp), 1920© Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015

Presenting oneself as androgynous was used by Surrealists especially, because it subverted typical expectations of how women were portrayed in art, and it sometimes even caused controversy within the art world. It is essentially a way of fighting back against the fetishisation of the female body and against the male gaze, and the fact that Woodman was a teenager when she first started making these images makes it all the more impressive. The idea that “acting feminine” is an ongoing performance brought on by social expectations was famously explored by Simone de Beauvoir in her book The Second Sex (1949), “one is not born but rather becomes a woman,” which can be interpreted as an explanation of how traditionally feminine behaviour isn’t the natural state of being for people born to the female sex. Furthermore it can be said that the use of androgyny and femininity in art and photography, not only by Woodman but by everyone, is more of a statement of confrontation against traditional femininity than conformity to gender norms.

WOODMAN IN RELATION TO FEMININITY-

“In 1986 Abigail Solomon-Godeau presented Woodman as a prodigy who could be understood as critiquing the historical and linguistic construction of femininity and trying to produce an essentially feminist aesthetic” (Townsend 2006). Often in highly posed and abstract positions, she mainly uses herself as the subject of her images as well as other women and the occasional man, almost always featuring nudity in a way that de-sexualises their bodies and creates a strange sense of experimentation and self-exploration, where the viewer neither feels like a peeping-Tom nor engaged in a sexual act, but rather a witness to her grasp of her own femininity and sexuality, which is fluid and questioning in nature.

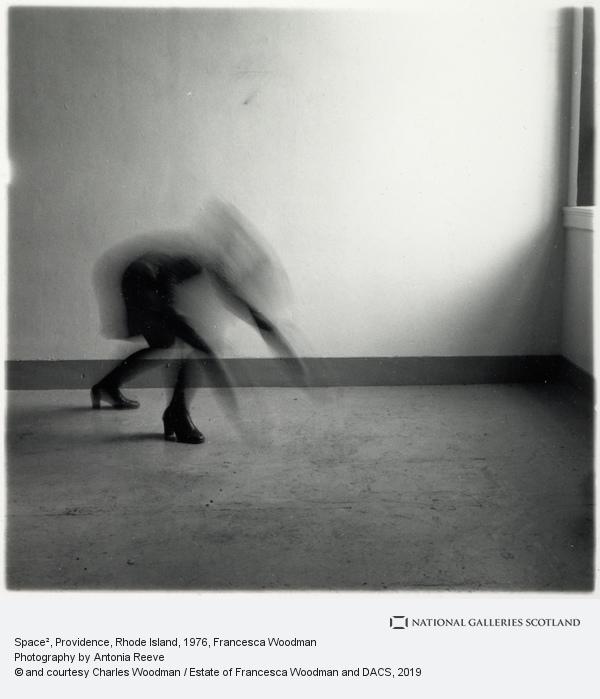

‘Space², Providence, Rhode Island’, Francesca Woodman

This can be explored by Butler’s theory of gender performance, namely “to say that gender is performative is to say that nobody really is a gender from the start” (Butler, 2011). Below are a few examples of Woodman’s use of nudity in her artwork in which there is no sexual aspect, which is in direct contrast to the vast majority of art (not just photography) featuring nude women. This could be interpreted in a couple ways, for example that it is simply the experimentative steps of a teenager who does not fully see herself as a sexual being yet. On the other hand, it could be perceived as a deliberate and premeditated attempt to break barriers surrounding women in the world of art by using her own body to contradict the idea that the female body can only be a sexual thing. Whichever of these interpretations one subscribes to, there is a prominent sense of androgyny and fluidity in these images and, indeed, throughout Woodman’s whole body of work, that demonstrates her incredible talent and capability to provide actual meaning and thought alongside aesthetically and technically pleasing artwork.

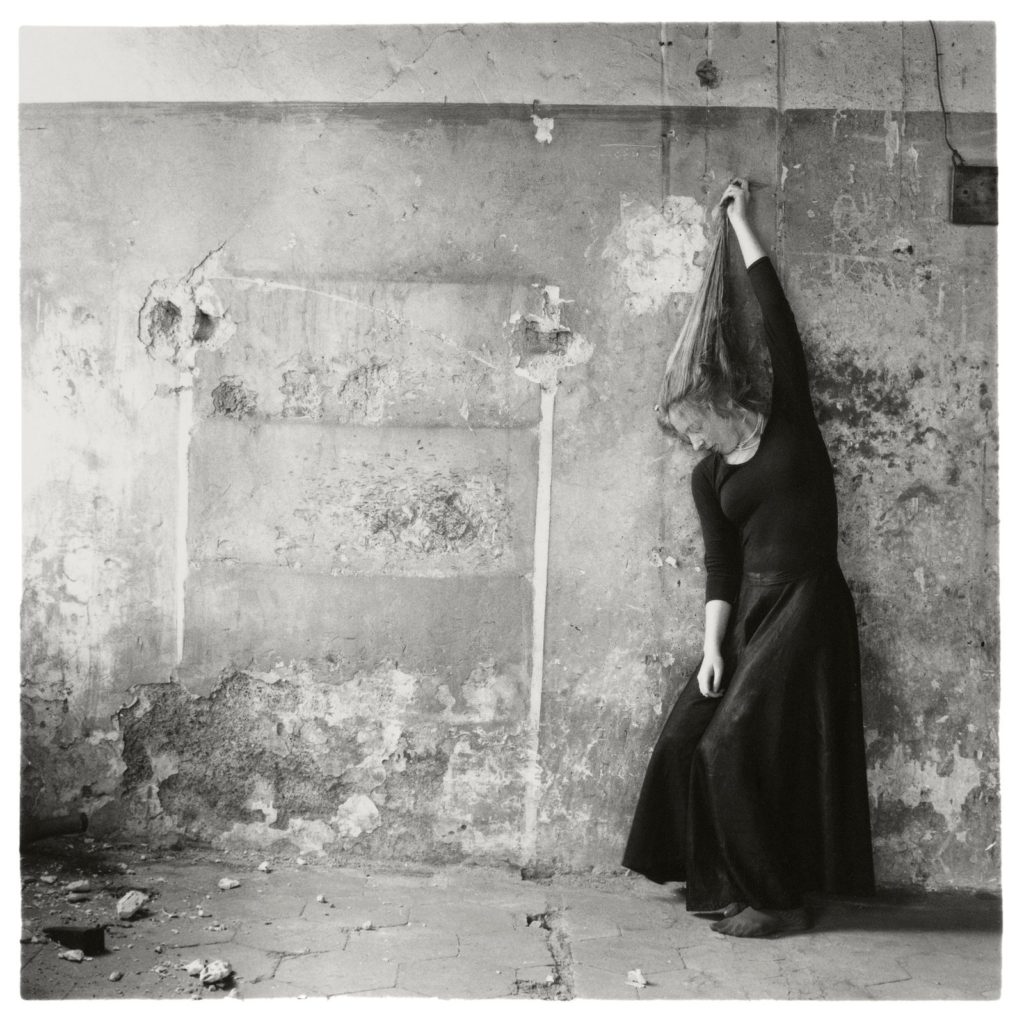

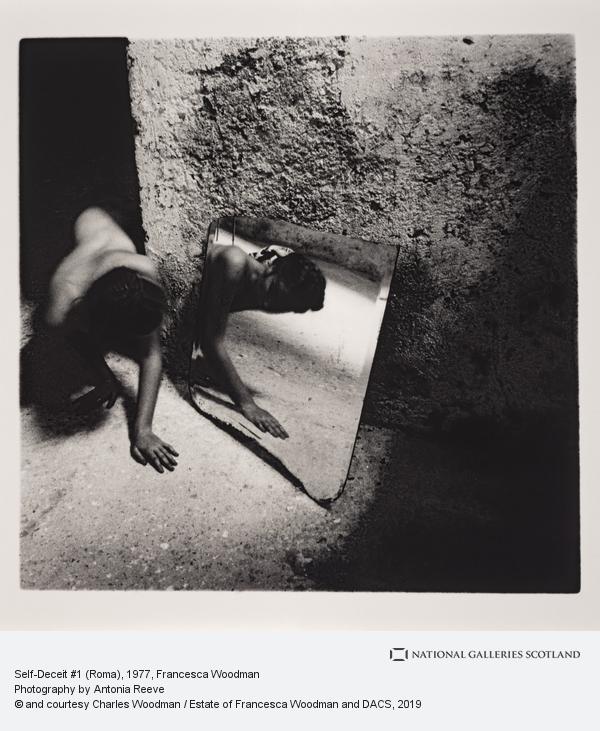

Self Deceit #1 (Roma), Francesca Woodman

Woodman’s signature use of long exposure to achieve a blurred body has been construed in many different ways, but most often as a form of disappearance. She is essentially hiding herself in the environment she chooses to surround herself in, but for what reason? The far-left image features a nude Woodman creeping around a corner on her hands and knees to face a mirror. It is one of the few images where the camera blur does not obscure her face, and her use of a mirror to reflect the camera’s “eye” back onto itself gives us an insight into how she sees herself. She appears curious, but tentative and maybe even fearful, revealing how her teenage self is going through a period where her identity and self-perception becomes important. She was nineteen at the time this was taken, so although she may not have known it, she was only a few years away from the end of her career and her life. The second image is different in that, while she is still fully nude, her entire body is obscured by blur due to her manipulation of the camera’s exposure, and her face is not visible. She has positioned herself within a hole in the headstone of a grave (a common feature of some older graves), and so is, in a rather morbid way, encasing herself in death. This could symbolise how she feels like herself and her body is trapped within life itself, or possibly how she sees death as a way of “passing through” to another place. The key point is that her body is not meant to be perceived as sexual in any way, even though she is entirely nude, which feels very modern and liberating. Another interpretation of this image is that it is the way her body is literally emerging from childhood into womanhood, using the grave as a metaphor for this. Any way it is perceived, it is clear that Woodman uses her signature long exposure technique to further present her interpretation of her own femininity and sexuality in a vague and androgynous manner.

COMPARING WOODMAN TO MICHALS-

One of Woodman’s most obvious influences- and also one of the only ones she acknowledged as an influence on her artwork- was Duane Michals. He is an American Surrealist photographer, born in 1932, who mainly creates cinematic narratives through sequences of highly staged images, but also has taken many portraits of influential artists, such as Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp, over the course of his career. There are several clear similarities between his body of work and Woodman’s, possibly most obviously their use of long exposure techniques to intentionally blur the subjects of their photography.

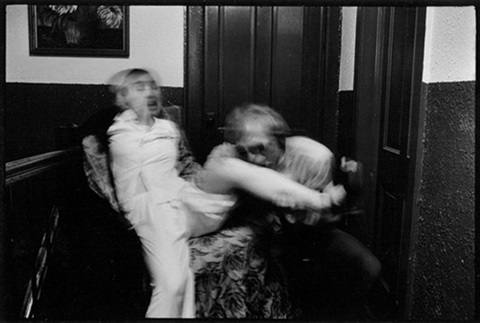

People Eat People (1974), Duane Michals

People Eat People (1974), Duane Michals

Above is an example of both Michal’s creation of narratives through sequences as well as this photographic technique. The dark background in focus contrasted against the bright white and blurry figures in the foreground help to make this photo-series impactful and emphasise the emotions portrayed in the second image: fear, shock, horror, hunger. Michals uses blur in a different way to Woodman, however, using it to further the narrative and his intentions behind the photograph rather than directly impacting the perception of the main subject, like Woodman does.

Duane Michals

Francesca Woodman

Both artists also use mirrors in their work as a way to portray how the subject sees themself, whether positively or negatively. Michals’ image above can be interpreted as reflecting how the subject has a distorted perception of themselves, and Woodman uses it in a similar way, but in a less literal manner. They both have fairly high tonal ranges which add depth and make the images more interesting overall, capturing the attention of potential viewers. In Woodman’s image, the whitest part of the photograph is the floor directly behind the subject’s head’s reflection in the mirror, which serves to make it the main focal point. In Michals’ photograph, the whitest part is clearly the strip of wall behind the mirror the subject is holding up, which has the same effect as Woodman in that the subject’s reflection is very obviously the intended main focus of the image as a whole.

‘Untitled, from Angel Series, Rome, Italy’, Francesca Woodman

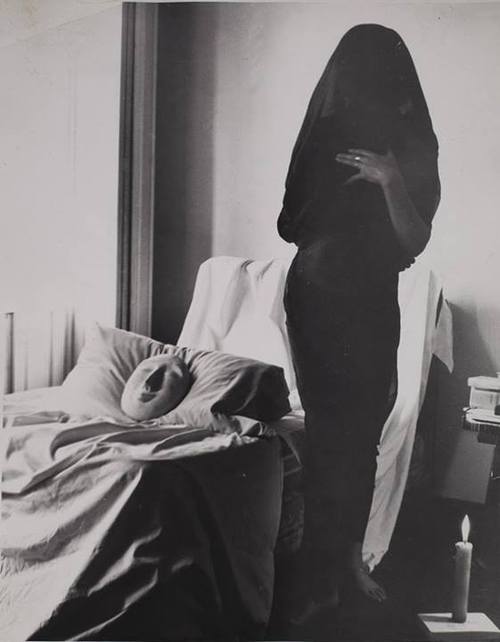

Another notable area Michal’s influence on Woodman is the use of angelic imagery, shown above. “The Fallen Angel” (1968) is a photo-series about a girl and an angel who succumbs to his lust for the girl and kisses her but loses his wings as a result and is overcome by guilt and shame. This is a more traditionally Biblical portrayal of angels; the angel being male, and the concept of human sexuality is surrounded by shame and other negative emotions. This is in contrast to Woodman’s use of angels in her “Angel Series” (1977) in Italy, where she is the angel herself and is also nude, but in a way where it feels liberating and joyful overall rather than shameful. These differences can be attributed to both Woodman’s youth and her femininity altering her perception of angels and the nude human body, contrary to Michals, who is male and was 36 at the time of the “Fallen Angel” series. Michals’ photo-series also features a nude female woman, who is lying on her side on the bed. Her body is entirely facing the camera (and therefore the viewer) and her role in the narrative is clearly only as an object of lust and desire, the temptation that the angel feels and the ultimate cause of his suffering. This is (unfortunately) standard in the world of art and photography, as explained in the beginning of this essay, and further illustrates how ground-breaking Woodman’s work was in presenting a different approach to the portrayal of female nudity and femininity in general.

CONCLUSION-

“Woodman’s linking of the woman´s body to the walls and surfaces it seems bonded to repeats the theme of the body as itself a surface.”

Abigail Solomon-Godeau, (1986) “Just Like A Woman”, published in: Photographic Work

In essence, Woodman’s exploration of her own femininity feels almost like an attack on the stereotypical perception of femininity expected from a teenage girl, in that she is open and confident about her nude body without fetishising or overly-sexualising it in the way that many of her male contemporaries were doing at the time, the way her influences had done before, and in the way that (especially male) artists and photographers have continued to do since her death. She photographs her body within almost exclusively abandoned and dilapidated spaces in a Gothic-like manner, which on the surface reduces it’s perceived “worth” but in actuality elevates her message and the emotions she conveys to even higher platforms. Although she never credited many, if any, other photographers and artists as direct influences on her art, but the few she has can clearly be seen throughout her whole body of work. For example, the extended metaphor of angels and general angelic imagery can be attributed to Duane Michals, and she has often been grouped within the Surrealist art movement as a result of the often strange and eerie tone we get from her photographs. Her age is also an impactful factor on her perception of femininity and how she represents her sexuality, as youth often sees the subjects of sex and gender identity as far more fluid and questioning than older generations tend to. In my opinion, her continued use of the nude female body is one of the most important components when evaluating how she explores femininity, because she completely subverts the traditional expectations of a passive, naïve, yet somehow intensely sexual woman, and replaces it with this image of a person who is at the same time shy and confident, trapped and free, and, to a degree, mocking the viewer’s shock at these unexpected sights.

BIBLIOGRAPHY-

- Butler, J. (2011) Your Behaviour Creates Your Gender.

- Mulvey, L. (1975) Visual Pleasures. Screen

- Niedda, M. (2020). Feminist and queer studies: Judith Butler’s conceptualisation of gender.

- Solomon-Godeau, A. (1986) Just Like A Woman. Photographic Work

- Townsend, C. (2006) Francesca Woodman: Scattered in Space and Time). London: Phaidon Press Ltd

Chloe, so far an excellently written essay introduction and pg 1. I have made a few minor correction directly into your text (mainly sentence structuring) and written a few things for you to consider in read.

Also amended referencing system using Harvard both in-text references and a bibliography.

You are demonstrating high level of comprehension of very academic texts and theories and it looks very promising.

Lastly, I would like to see how your film project is developing and make sure you publish some blog posts with footage (visual & sound) and show your film editing process too.

Good work, keep going!

MT