Monthly Archives: January 2021

Filters

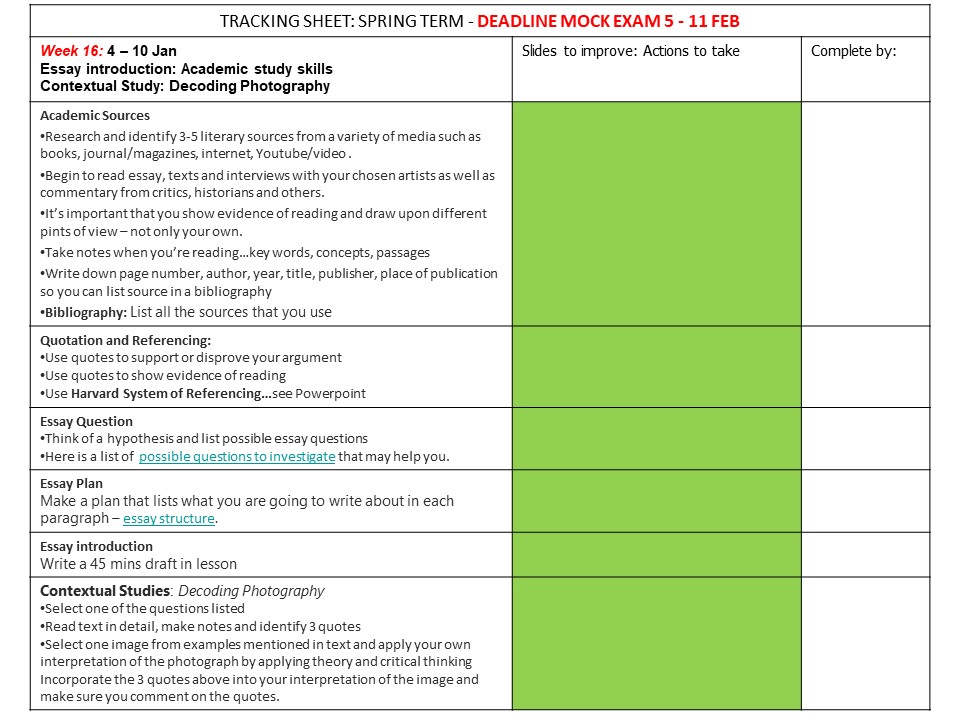

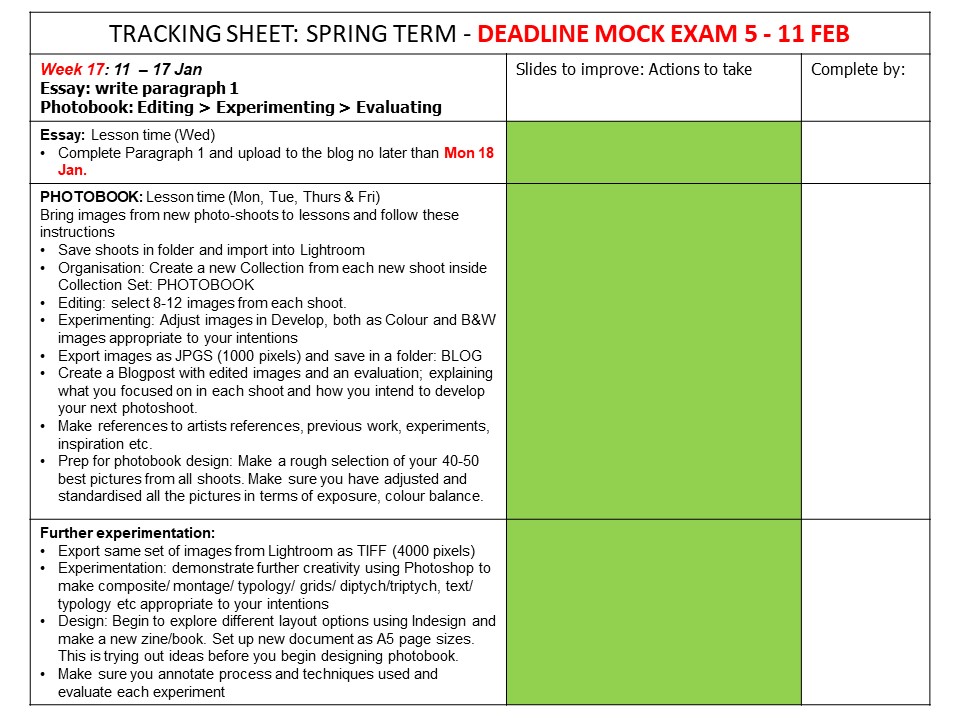

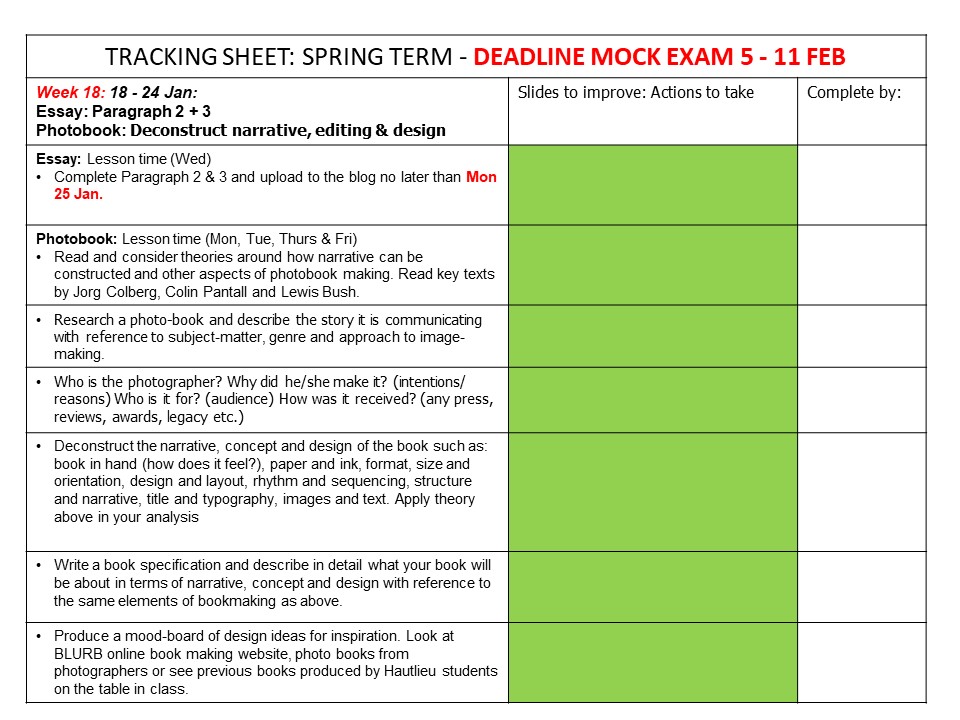

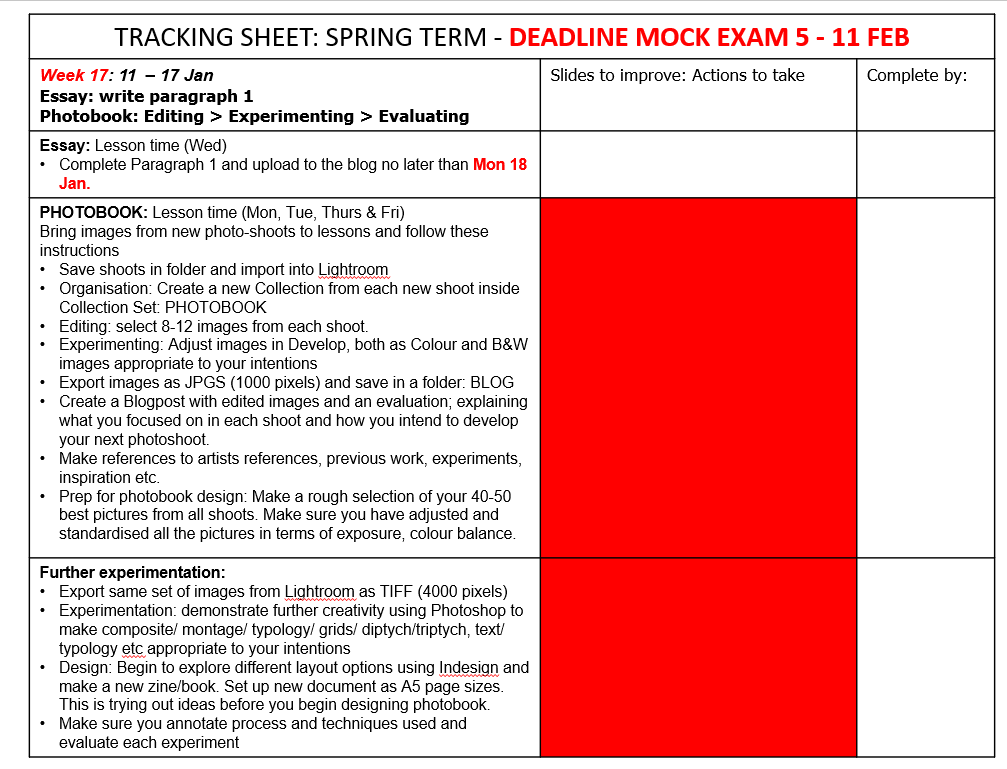

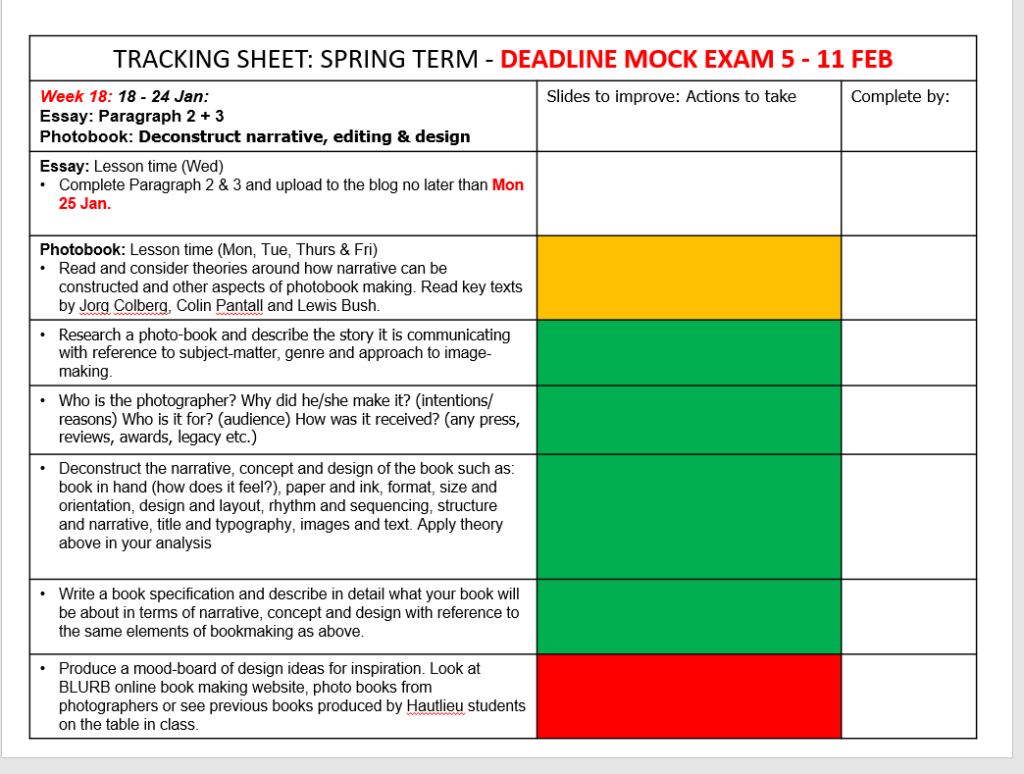

Self Tracking & monitoring

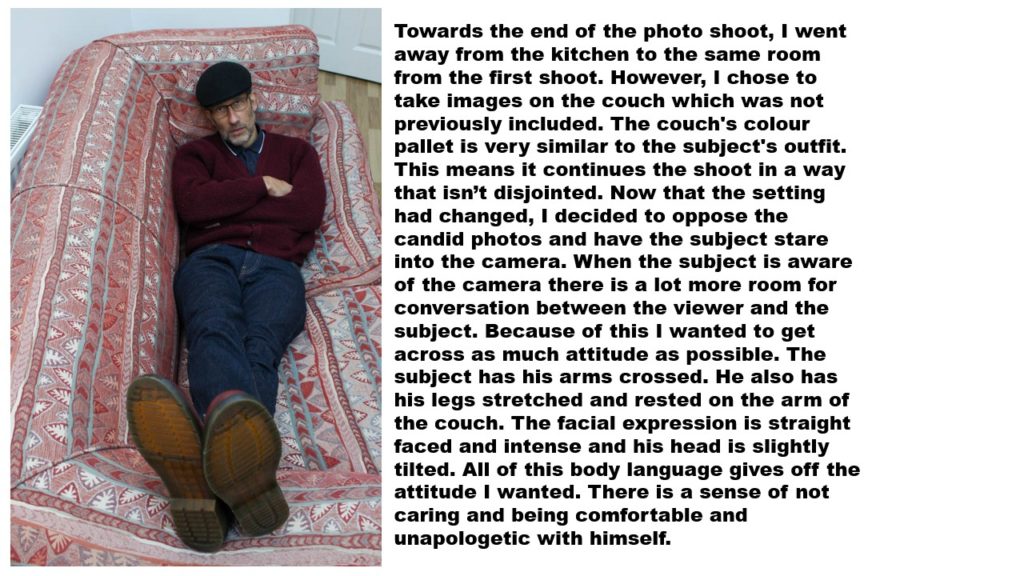

SHOOT 2

Theory: Art Movements/Isms

Post Impressionism

After researching Richard Billingham as part of my artist references, I discovered that hiss first initial love for art was inspired by Van Gogh whose paintings involved every day life. He enjoyed how certain post-impressionist painters could situate the figure of a person in an interior really well – as if they are part of the interior themselves. Since I am referring mainly to Billingham, I feel it is best to explore Post-Impressionism to see how it inspired the art that he created.

Post-Impressionism is a predominantly French Art Movement that developed roughly between 1886 and 1905. It emerged as a reaction against Impressionists’ concern for the naturalistic depiction of light and colour. This movement tends to to emphasise broad qualities or symbolic content. Post-Impressionists, especially Vincent Van Gogh extented Impressionism while rejecting its limitations – they continued to use vivid colours, often a thick application of paint, and real-life subject matter. However they were more inclined to emphasise geometric forms, distort form for expressive effect and use unnatural or arbitrary colour.

The Post-Impressionists were dissatisfied with the triviality (lack of seriousness) of subject matter and loss of structure in most Impressionist paintings. Paul Cezanne, especially set out to restore a sense of order and structure to paintings in order to “make of Impressionism something solid and durable, like the art of the museums”. He achieved this by reducing objects to their basic shapes while retaining the saturated colours of impressionism.

Artists that are included in this movement are: Paul Cezanne, Odilon Redon, Henri Rousseau, Paul Gauguin, Vincent Van Gogh, Charles Angrand, Henri-Edmond Cross, Maximilien Luce, Georges Seurat etc.

Post-Impressionism can be described as ‘a window to the artist’s mind and soul’. This is relevent to my personal study as my film is looking into my life, living with a poorly family member. My film will be similar to Post-Impressionism in the fact that my emotions and thoughts will be displayed throughout the moving images. Symbolic and highly personal meanings were displayed throughout this ‘ism’, Van Gogh especially looked to his memories and emotions in order to deeply connect with the world around them instead of simply depicting the natural world that surrounded him.

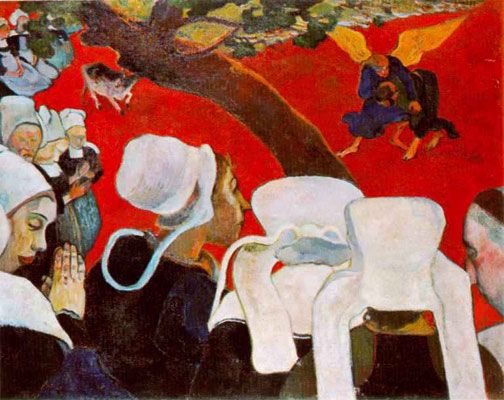

Consider this painting by Paul Gauguin who studied in the North of France where the unique history and customs represented a degree of spiritual freedom and primitive candor for Gauguin.

This painting depicts a revelatory vision of ‘Jacob’ wrestling with an angel, clearly delineates reality and spiritual manifestation through aesthetic form. While the ground of churchgoers who experience the vision is in the foreground, the Biblical struggle appears in the background, surrounded by a two-dimensional, brightly coloured plane. Gauguin relied upon the abstraction of the red ground to communicate the space of the vision as well as heightened emotions present at a religious revelation. As this work demonstrates, Gauguin rejected the conventions of industrialised modern society, in both his art and his life, through romanticised evocations of the primitive, the incorporeal, and the mystical. At first glance, it may not appear to be the most aesthetically pleasing image. However, as I was saying in my artist research on Richard Billingham, sometimes it is not about the aesthetic nature of a photo or a film but yet the meaning that are being conveyed behind the footage or image.

QUOTES

“I refused to board the Impressionist ship because I found the ceiling too low. . . . Real parasites of the object, [the Impressionists] cultivated art solely on the visual field, and in a way closed it off from what goes beyond that and what can give the humblest sketches, even the shadows, the light of spirituality. I mean a kind of emanation that takes hold of our spirit and escapes all analysis.”

Artist Odilon Redon, To Myself: Notes on Life, Art and Artists, trans. Mira Jacob and Jeanne L. Wasserman (New York: George Brazillier, 1986), 110

“Claude Monet’s landscapes are . . . the extremely sensitive shapes of our thoughts.”

—Critic Octave Mirbeau, “Claude Monet,” L’Art dans les Deux Mondes, March 7, 1891, reprinted in Mirbeau, Combats esthétiques, 430–431.

“It is no easier to explain Cézanne’s [fame] than to explain the man himself.”

—Artist Maurice Denis, “Cézanne,” L’Occident, September 1907, reprinted in Maurice Denis, Le ciel et l’Arcadie, ed. Jean-Paul Bouillon (Paris: Hermann, 1993), 129ff.

“I arrange lines and colors so as to obtain symphonies, harmonies that do not represent a thing that is real, in the vulgar sense of the word, and do not directly express any idea, but are supposed to make you think the way music is supposed to make you think, unaided by ideas or images, simply through the mysterious affinities that exist between our brains and such arrangements of colors and lines.”

—Artist Paul Gauguin, in Eugène Tardieu, “Interview with Paul Gauguin,” L’Echo de Paris, May 13, 1895, reprinted in Guérin, Paul Gauguin, 109

“However sad the chosen subject might be, however dreary the picturesque element that compose it, the painting will never . . . give the impression of sadness if the dominant characteristics of the lines, colors, and tone do not agree visually with the feelings the artist is seeking to express.”

—Artist Maurice Denis, “L’époque du symbolisme,” Gazette dea Beaux-Arts, March 1934, reprinted in Denis, Le ciel et l’Arcadie, 176–177

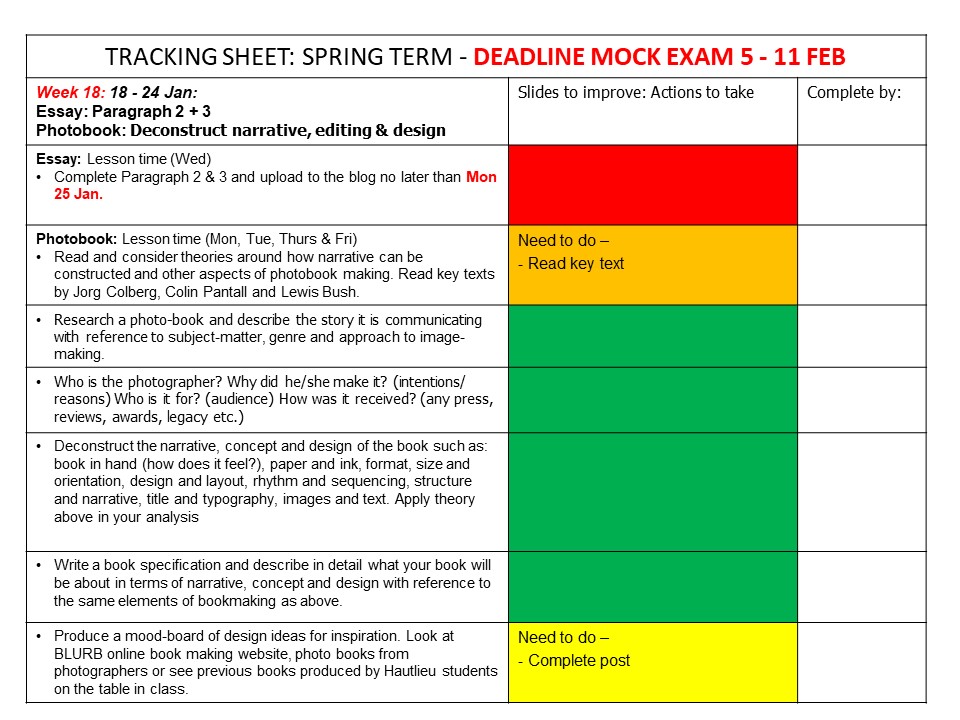

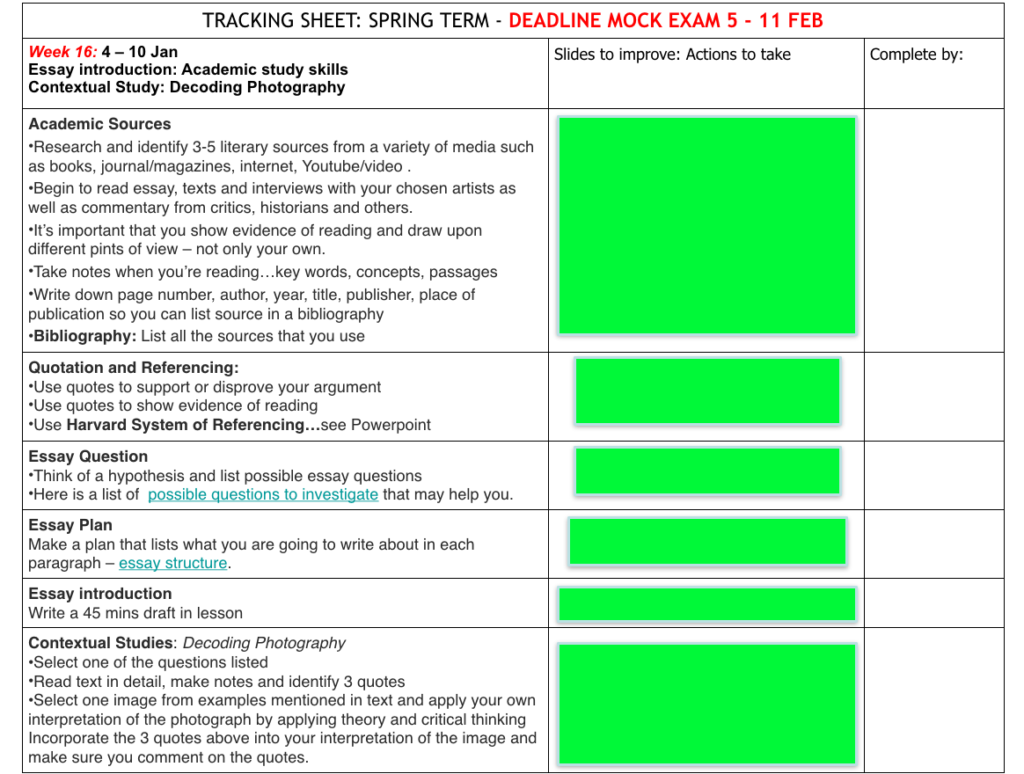

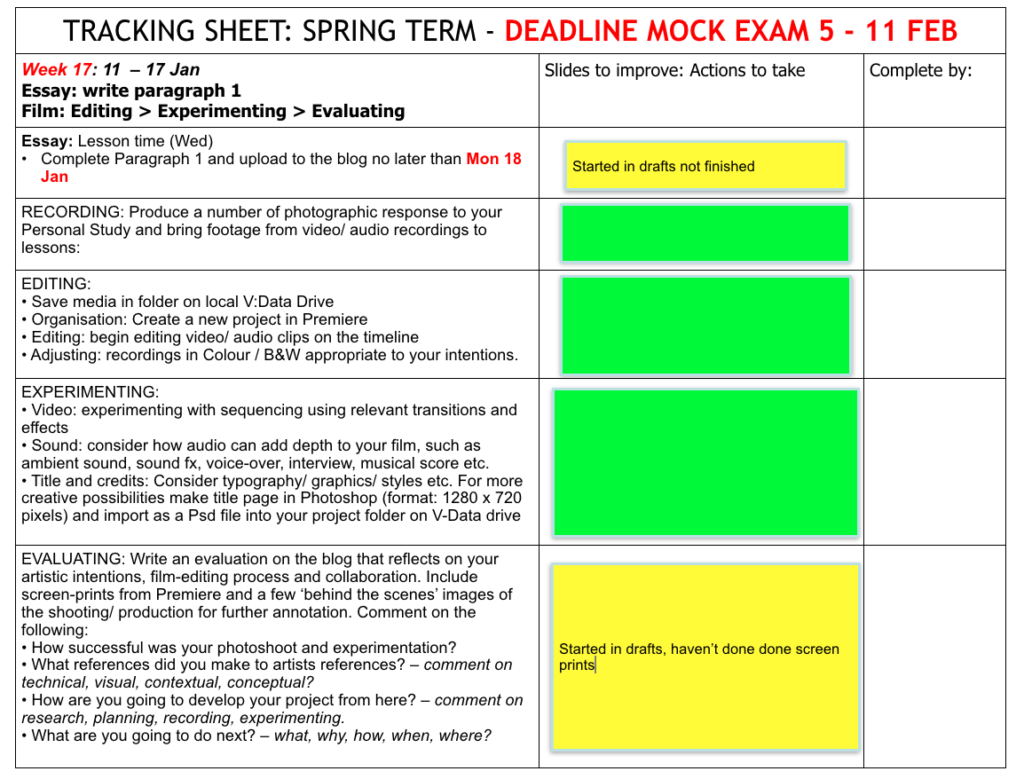

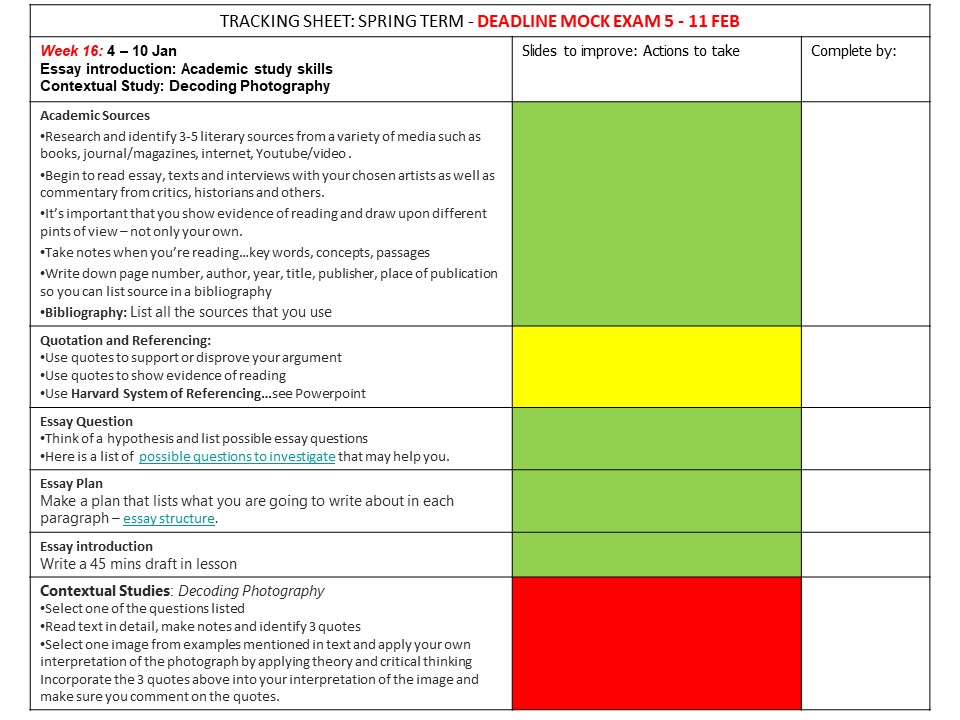

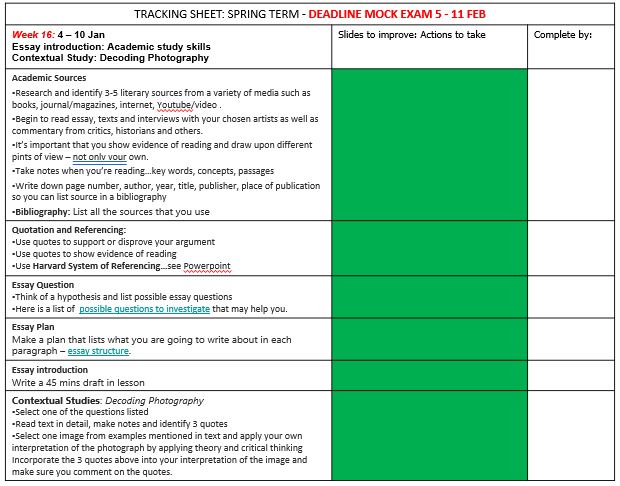

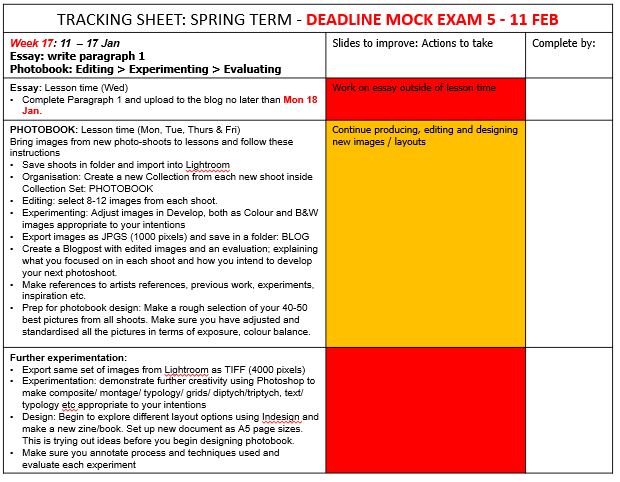

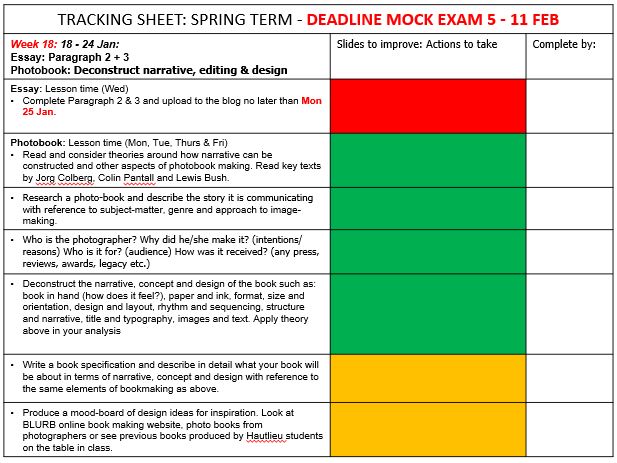

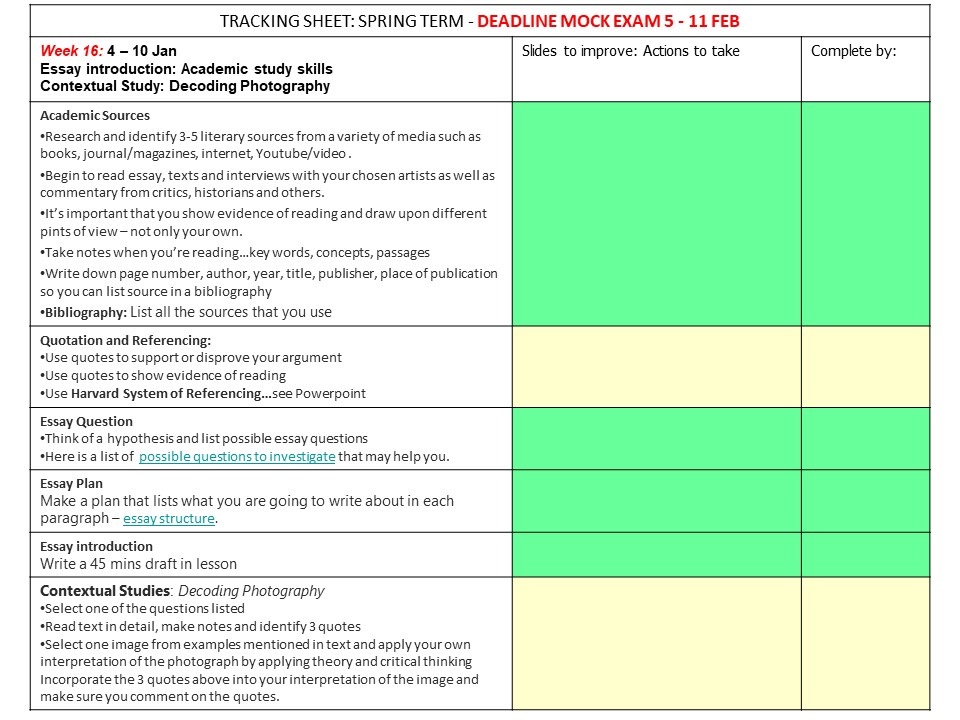

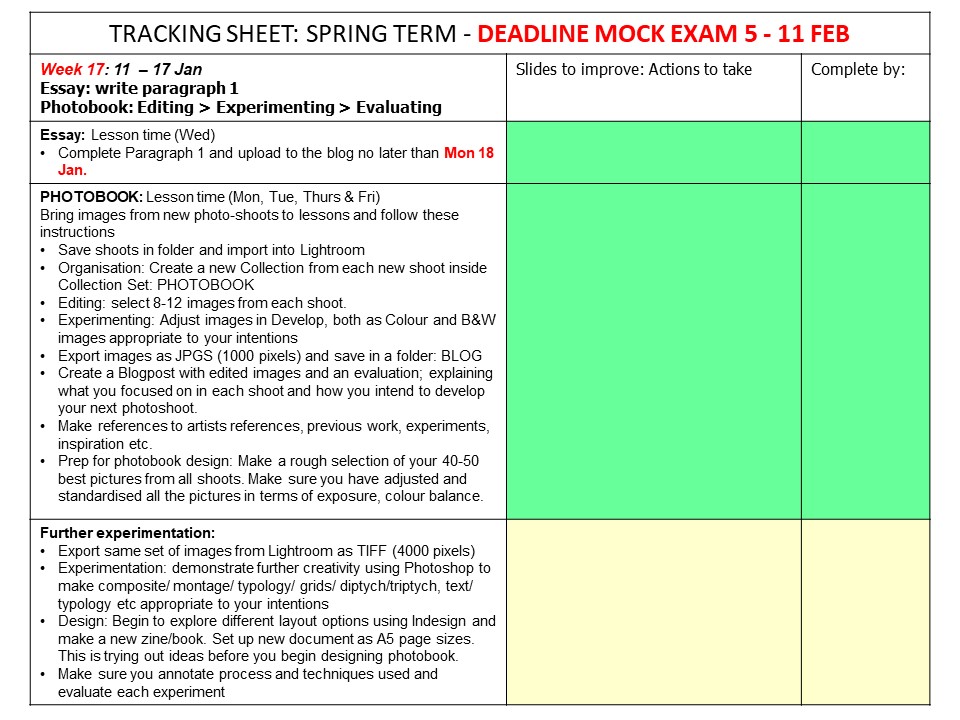

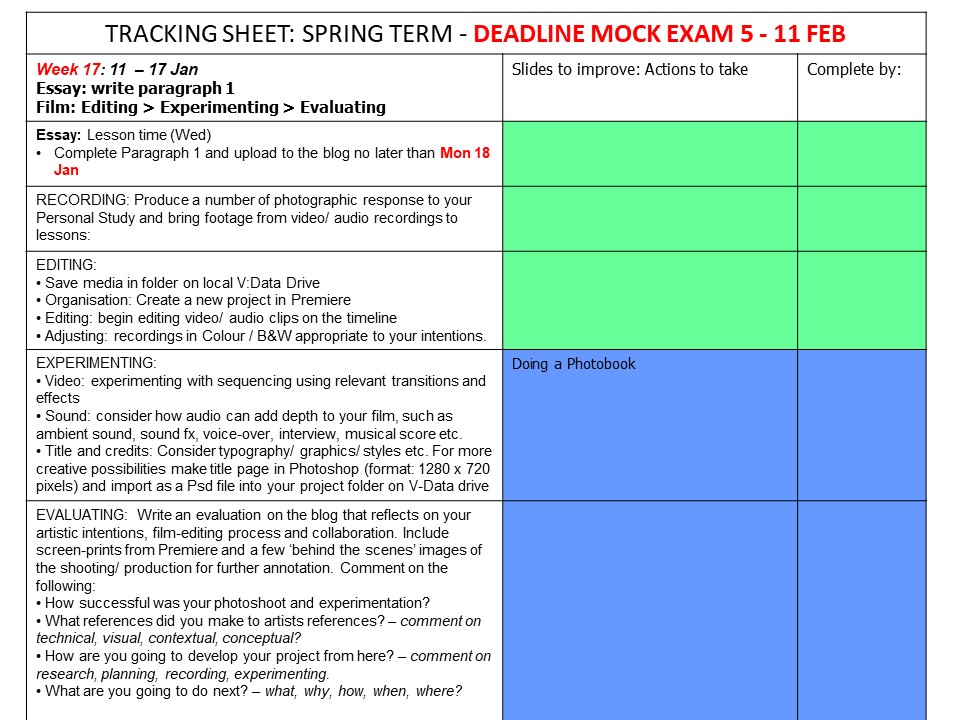

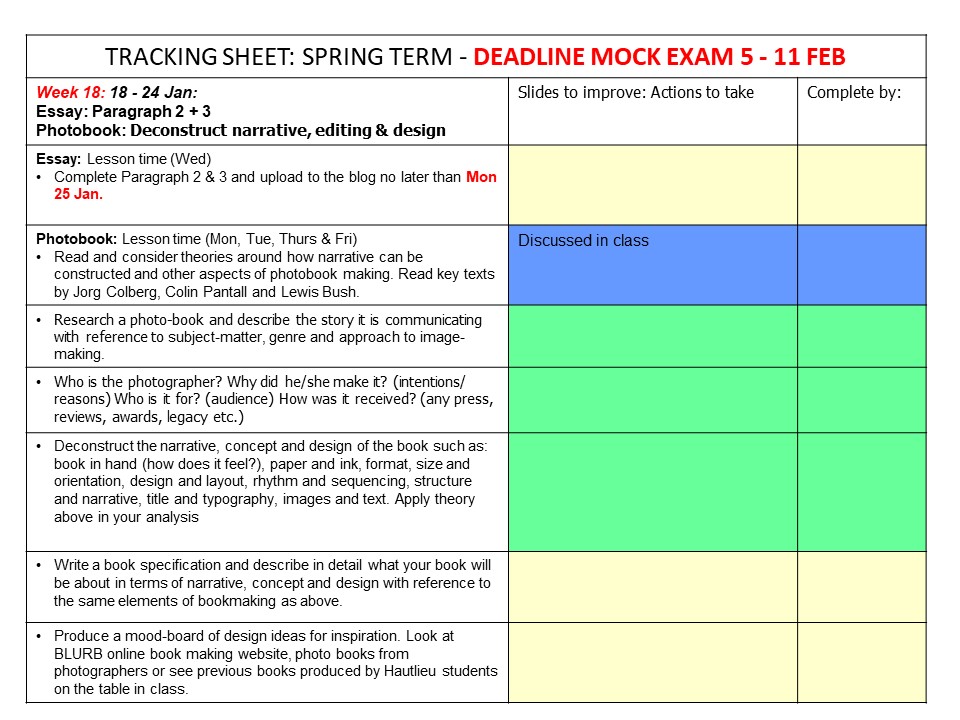

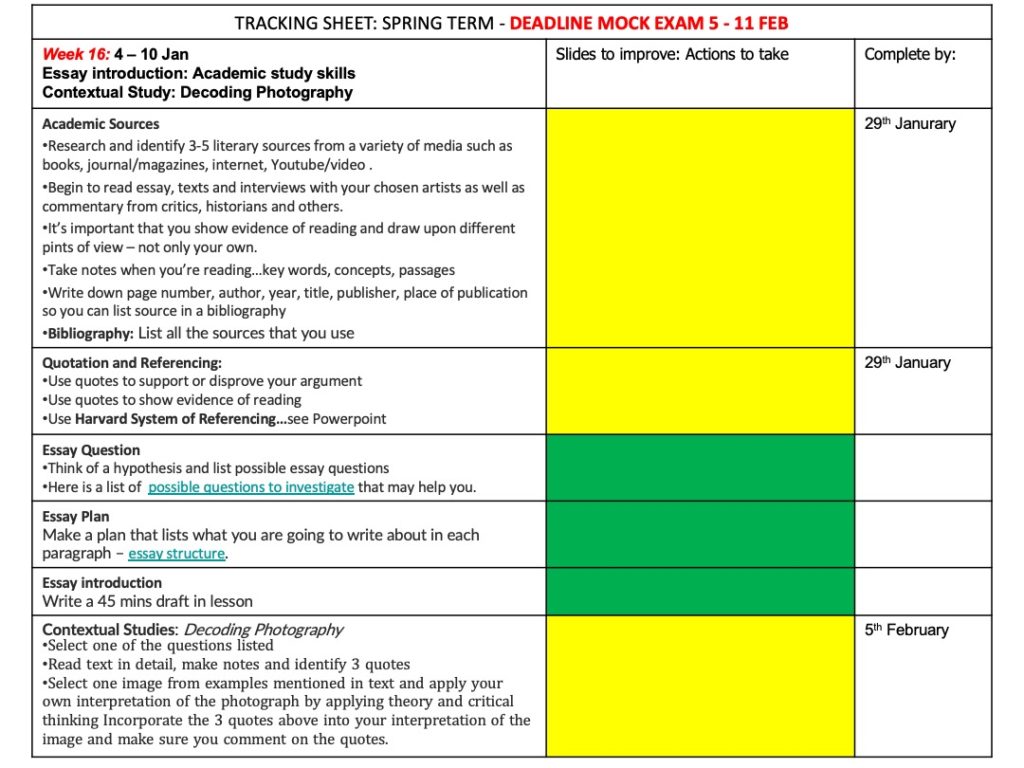

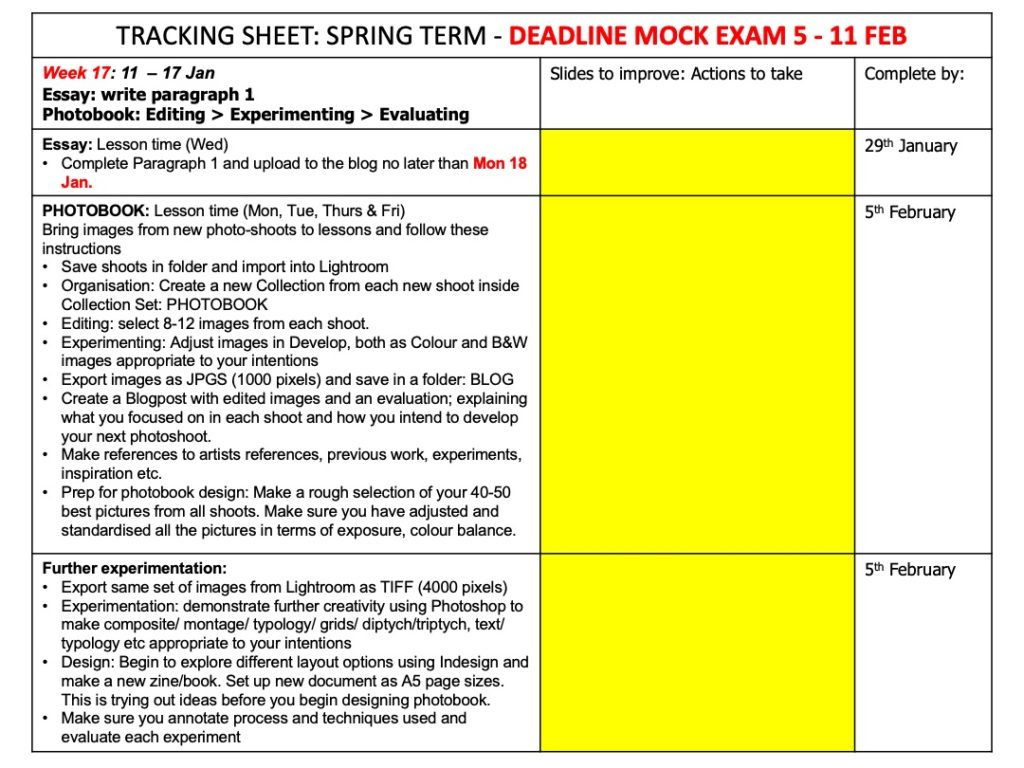

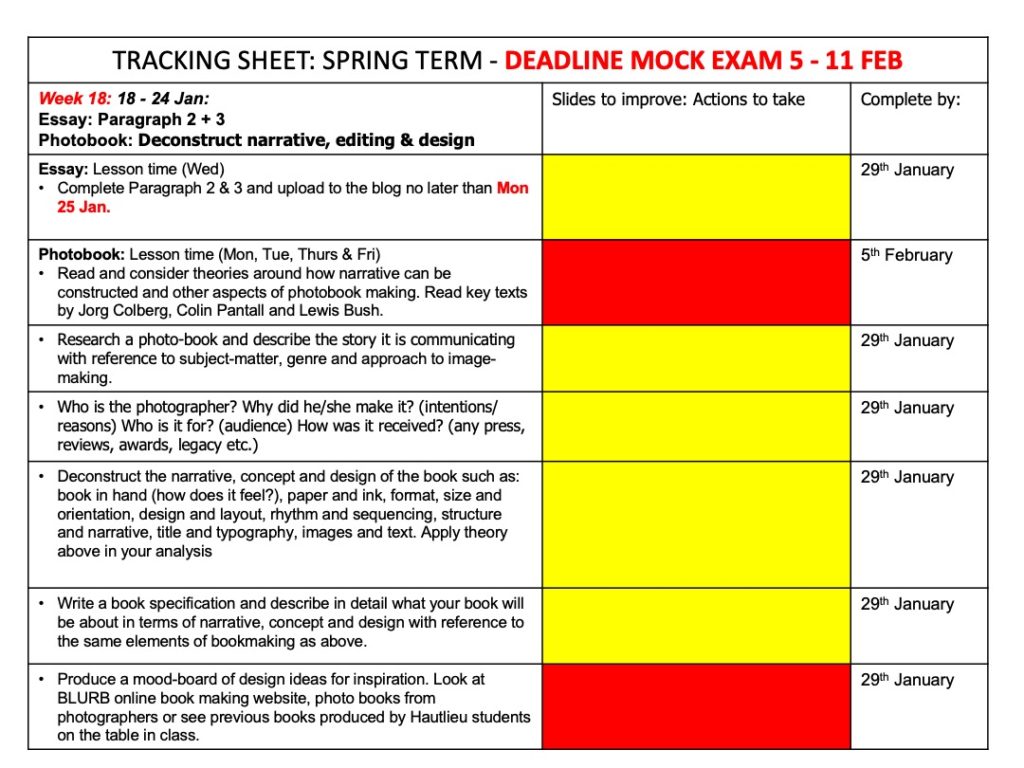

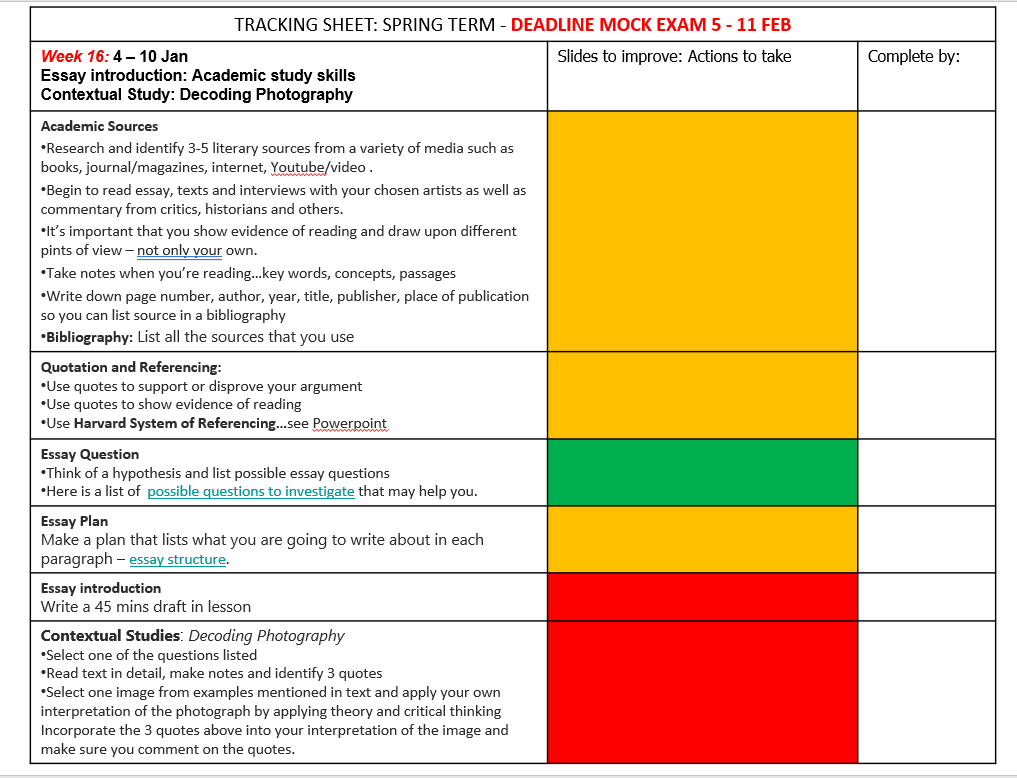

Personal Tracker

UPDATE – PLANNER

self tracking and monitoring

SELF TRACKING AND MONITORING

Personal Tracker