First attempt of faded / see through effect

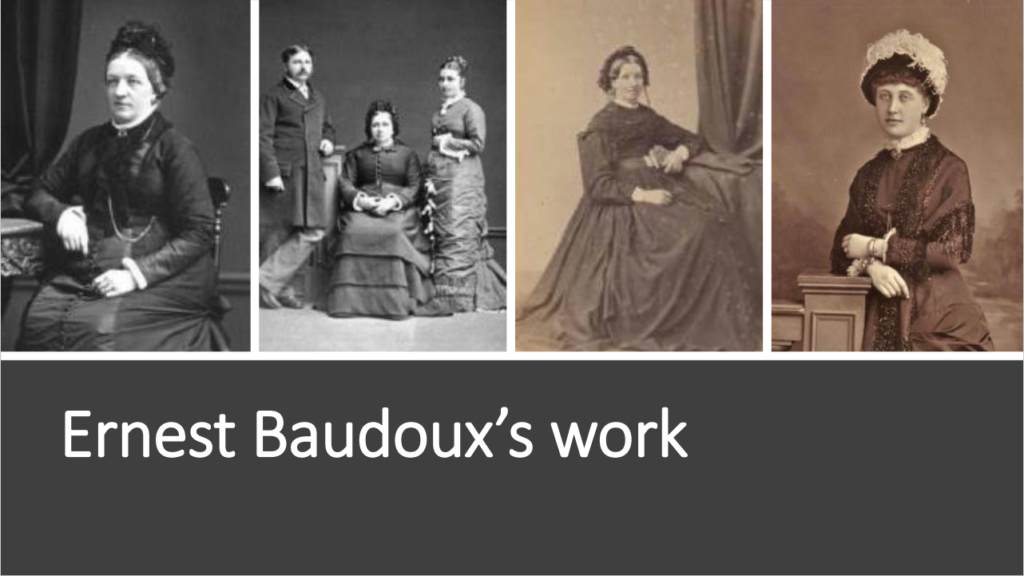

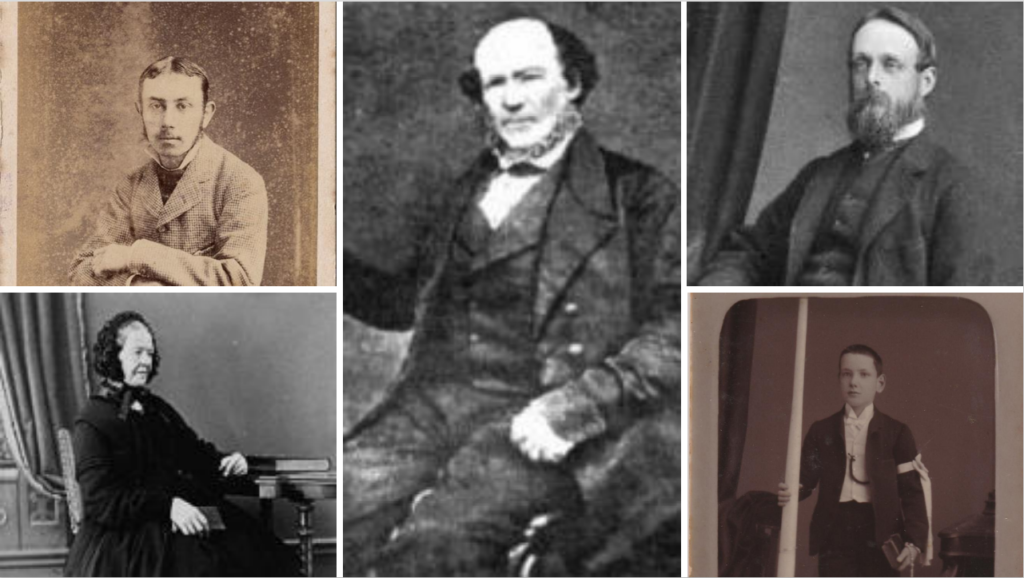

example of quotes

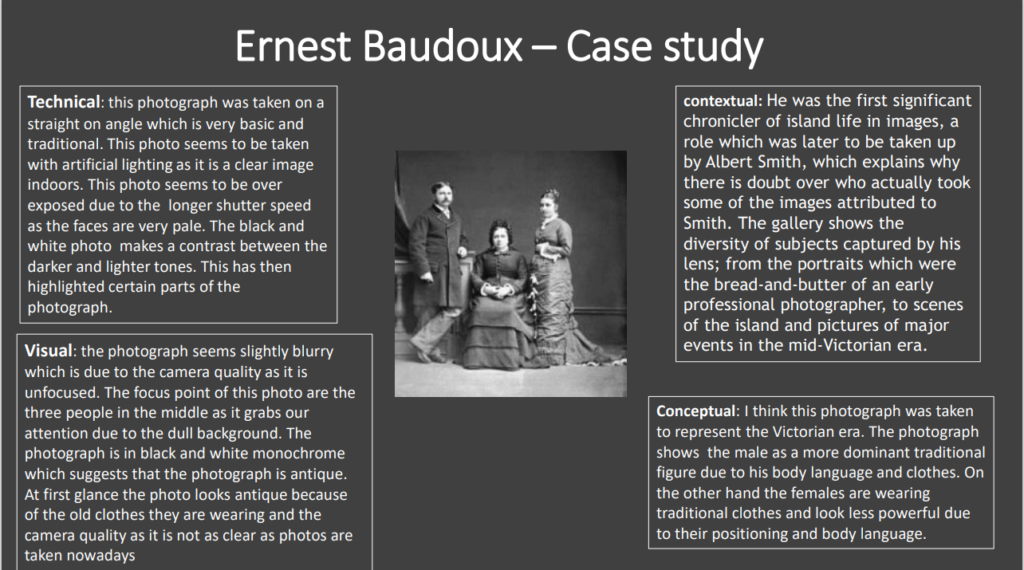

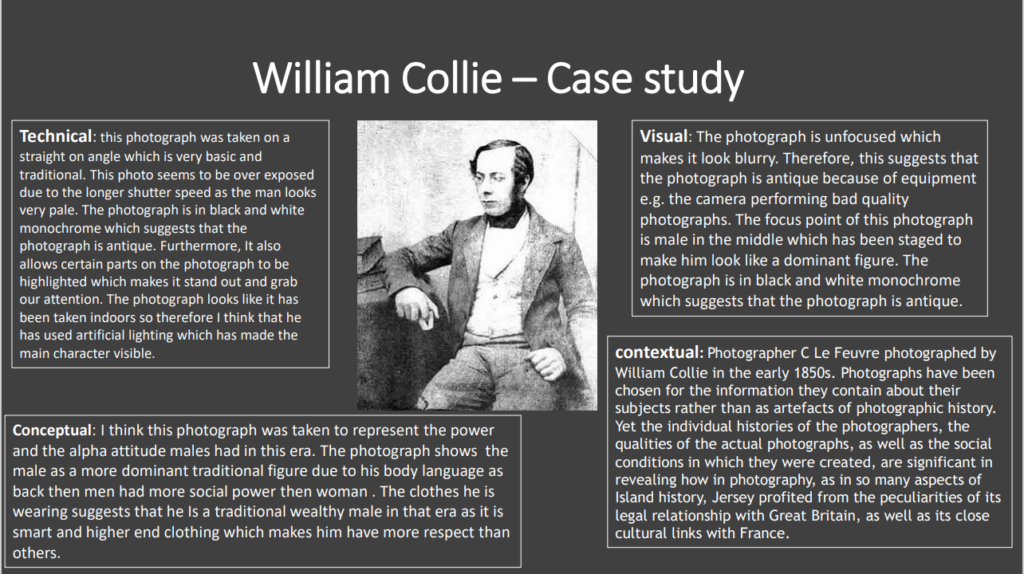

examples of studio portraits

First attempt of faded / see through effect

example of quotes

examples of studio portraits

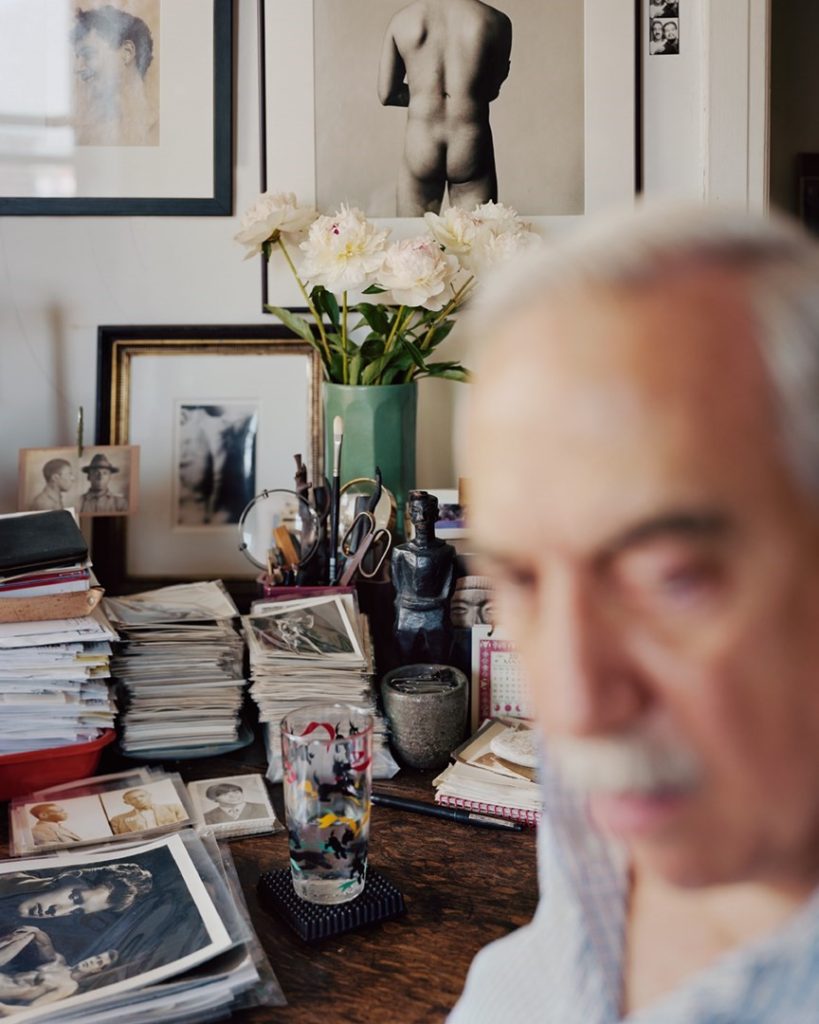

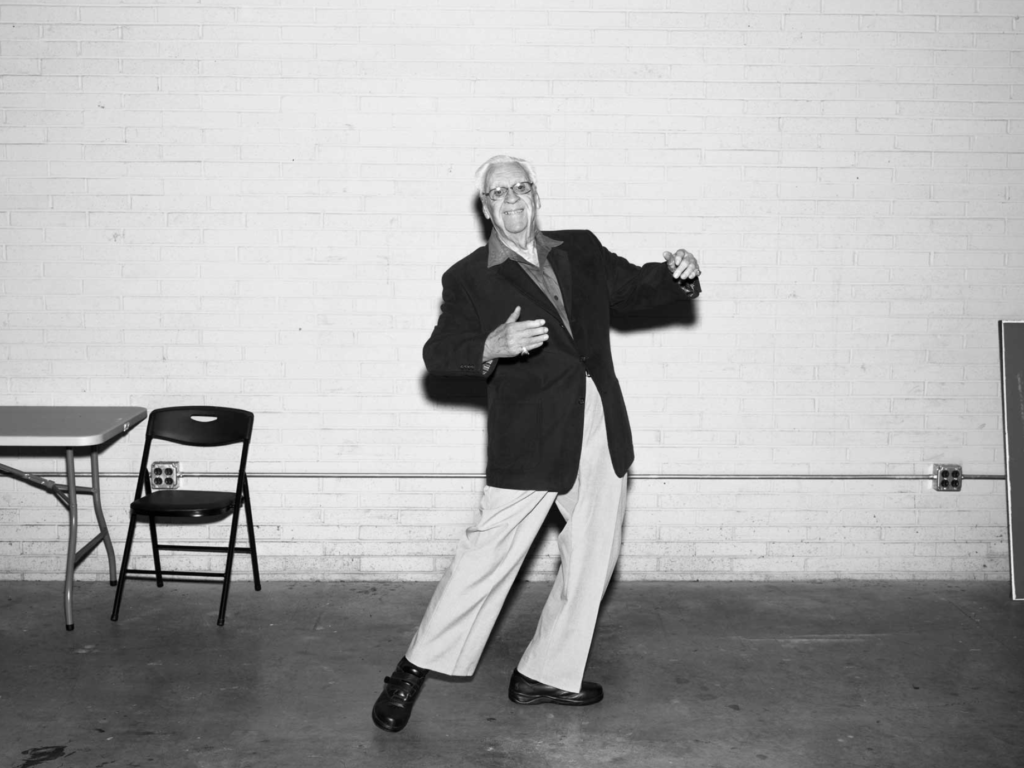

Alec Soth was born in 1969 in the USA and his work mainly features American stories, particularly the midwest. He has described himself as focusing his “photographic career on finding chemistry with strangers” and making portraits of a wide variety of people from all walks of life, often in their own homes in the form of environmental portraits. In this respect, he is similar to Ernest Badoux. He has published several books, and the images below are all taken form his most recent publication, “I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating”, which is mainly comprised of environmental portraits of strangers in their homes.

“This is how photography works — this appreciation of all these surfaces, all this beauty. But you can’t quite get inside. It’s about making do with that.”

Contrasting Ernest Badoux’s black and white portraits taken in a studio environment, the tone of which is very formal, these portraits are colourful and taken from various different and more contemporary angles, giving them a more informal sense and creating the sensation that the camera lens is acting as the eye of the view. This, coupled with the fact that the subjects are (mostly) staring directly down the lens, adds to the feeling that the viewer is interrupting a private moment and intruding on their personal and private space, completely opposite to Badoux.

“When I photograph people, I want to find a new way to engage with them. Where it’s not driving around, snagging people, talking them into stuff they don’t want to do.”

Soth also differs from Badoux in the way that his photos are titled, simply being the subject’s first name and the city they live in, in stark contrast to Badoux’s formal and stiff use of titles (Mr, Mrs, Miss) and last names. This makes Soth’s portraits more personal and engaging than Badoux’s.

As well as portraits, he also included a few images titled as somebody’s “view”, which in themselves reveal little about the people who’s views they are, but more about what sort of environment they are living in. In a way this is still a very personal and intimate subject to photograph, as it’s what that person would see every single day as part of their routine, and so it is a central part of their life.

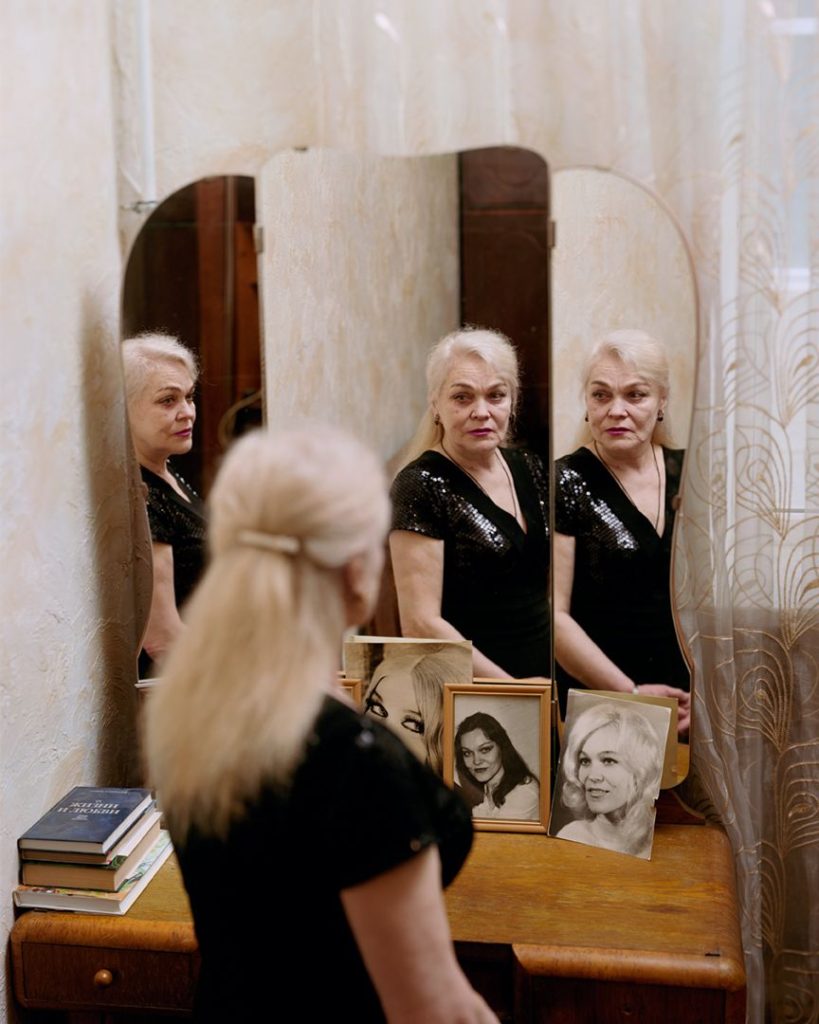

This image features much more symbolism than Ernest Badoux’s work, as its intention is more to tell a narrative and convey a meaning than simply document a person’s existence. This photograph could be said to carry a strong theme of identity, represented in the multi-faceted mirrors and the photo frames on the vanity. The way that the subject is looking back at herself from multiple angles as well as having pictures of her younger self (I am assuming) reveals how the passage of time has changed her and perhaps signifies a loss of identity or self-love. Her expression seems sad and tearful, which is by choice rather than necessity, as it was with Badoux’s photography, therefore it carries more emotion and significance in it. The lighting in this image is bright and from above, as it was taken inside, and the whole image’s colour palette is fairly monochrome and neutral, contrasting much of Soth’s other work featuring bright interiors and clothes. Finally, similar to Badoux, the subject is the centre of the image which draws the eye in and reinforces her as the main focal point of the photograph as a whole.

https://alecsoth.com/photography/projects/i-know-how-furiously-your-heart-is-beating

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/20/t-magazine/alec-soth.html

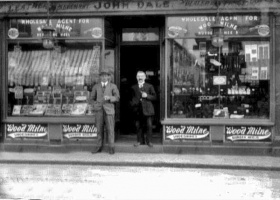

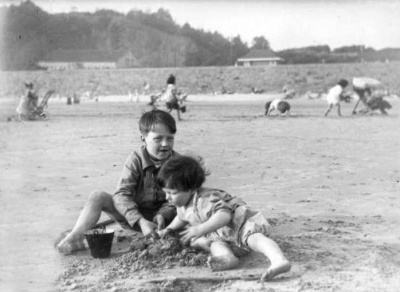

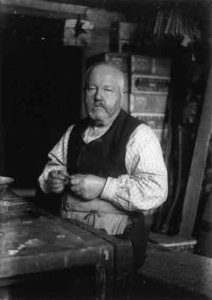

Born on the 3rd of January 1882, Edward Dale was a skilful photographer who took hundreds of landscape photos, including documentation of a range of events in Jersey, giving him the title of amateur ‘photojournalist’. Alongside these, Dale took a number of environmental portraits of islanders at the time.

In 1913, Dale entered the Jersey Eisteddfod (the photographic competition), resulting in him winning four 1st place prizes and two 2nd place prizes. He went on to have 40 of his images published on postcards in 1914, with many numbering as the most iconic images in Jersey during that time period.

As a photojournalist, the intention behind many of Dale’s photos were to purely document what and who interested him in Jersey, by scoping out individuals at their homes or places of work. This contrasts to the work of other photographers at this time, who tended to have studios set up in St. Helier where wealthy individuals to approach them and pay for formal portraits to be taken of them.

This image is presented in black and white, though not by intention, which reflects the era in which the image was taken. Additionally, the image is slightly out of focus, due to the long shutter speed of cameras of that time.

Dale’s image is an environmental portrait of an islander in Jersey between 1910 and 1920. As he was renowned for photojournalism, Dale likely took this portrait as he took a particular interest in the subject. Dale’s image portrays a man standing behind a penny-farthing bicycle in what appears to be a garage or shop of sorts, with a potential bicycle covered by a tarpon in the background. The man is dressed in a suit and an overcoat, an outfit implying that the subject doesn’t work for the place in which he’s standing. Perhaps he’s someone of higher importance, such as a manager or shop-owner, or perhaps he is a customer looking for a product.

Despite being a candid image, the wide and upright stance of the subject presents a natural sense of power, importance and dominance. His face is neutral but shows entitlement and privilege- with furrowed eyebrows and a strong gaze towards something, he seems expectant. Whether it’s an issue with the bicycle or a purchase he’s willing to make, the gaze makes it clear that he is more focused on the probable person attending him than on the bicycle, emphasising the dominance he has and the pressure he may assert on other individuals.

Furthermore, Dale utilities the natural light present through the skylight to illuminate the subject from above. This highlights the subject completely, keeping the main focus on him despite the busy background. The light also shows the polished shoes of the man, implying that he takes care of his appearance, further asserting the importance of the figure.

Moreover, the juxtaposition between the well-kempt, orderly appearance of the subject and the disordered, unorganised nature of the setting intensifies the idea that this is not the natural environment for the subject. This creates ambiguity as to who the person is and what role he played within Jersey society at the time.

Jafe is a French photographer renowned for infiltrating the world of the Japanese mafia (otherwise known as the Yakuza). Her photographic series ‘I give you my life’ gives a voice to the notoriously closed subculture of women associated with the Yakuza and in turn celebrates the bravery of those who have given their lives to the men behind it .

The women in her images said their motivations for getting their tattoos (irezumi) were about love and strength- being in and falling out of love, feeling strong and having the need to feel strong. The painful process for getting the tattoos includes being done by hand with a wooden handle and a needle which requires endurance and perseverance as they can take years to complete. Some women say their incentive for getting the tattoos were to “…live like the man I’m in love with”. Others say that looking at their naked body without tattoos made them feel “weak”.

Ultimately, the women feel as though their tattoos are a way to mark their independence from society. This takes bravery as they’re clearly conveying their allegiance to the Yakuza, placing themselves outside mainstream society. But this can also be seen as courageous due to the fact that the Yakuza men will never fully accept these women as members, due to the acute gender disparity within the group.

Whilst the Yakuza are major players in Japanese society, their women, often invisible, are not considered as members.

Chloe Jafe

Jafe calls attention to the differences between how these women view themselves and how they are perceived by men. In images which includes mixed gender groups, it’s apparent that the women hold subservient roles. But these ideals are juxtaposed by the portraits shes created. The images are highly intimate, not only breaking the gangster-stereotype the Yakuza holds, but also making them appear independent, empowered and formidable.

Contextually, this portrait by Jafe conveys a lot of meaning. With her only access to the Yakuza being through the men, her charming and harmless nature led to the wives and girlfriends viewing her with suspicion. Only after making friends and gaining the trust of these women was she able to capture this portrait.

The image is formal, with both parties knowing the image is being taken, it clearly represents the confidence and freedom from suspicion both parties have with one another. Additionally the placement of the subject shows the underground secrecy of the community. The background creates a highly ambiguous image, showing a lack of placement within society, highlighting how these women and individuals in the Yakuza are outlaws to Japan.

As well as emphasising context, Jafe’s choice of background keeps the focus on her subject. The contrast between the dark tones of the background and the clothing of her subject aids in this. The contrast is strong as the white clothing has taken in majority of the light when taking the image. This helps to show the power this individual has as it keeps the viewers’ gaze on the subject.

Jafe’s use of a low camera angle has a psychological effect on the viewer. Although the angle isn’t dramatic, it’s successful in presenting the subject as a strong and powerful individual. Moreover, the subject’s stance portrays her as independent and confident. The feet are squared off to the camera, the subject’s body language is open and she has an assertive placement of her hands, which further intensifies this sense of assertiveness in her character. Jafe’s subject displays a stern facial expression

In Japan, the cutting of hair can signify separating from past actions or thoughts. A woman with shorter hair is perceived as confident — as though they have nothing to hide. When the haircut is done out of deliberation rather than necessity, it can vividly represent an individual’s determination to make a dramatic break with their past. The subject in Jafe’s image has a strikingly short haircut, possibly differentiating between the person she was prior to the Yakuza and the person she is now. Furthermore, the confidence the subject shows despite being covered in stigma-ridden tattoos (irezumi) indicates that the woman isn’t afraid of being cast out by society and that she feels empowered by showing them.

Once upon a time….

A well rehearsed phrase that we are all familiar with, invoking childhood memories of fairytales, grandparents recounting old days or stories around the campfire. American novelist Kurt Vonnegut argued that the quality that defined good storytellers was simply that they themselves loved stories.

In this module we will study how different narrative structures can be used to tell stories in pictures from looking at photography, cinema and literature in photo-essays, film and books. We will consider narrative within a documentary approach where observation is key in representing reality, albeit we will look at both visual styles within traditional photojournalism as well as contemporary photography which employs a more poetic visual language that straddles the borders between objectivity and subjectivity, fact and fiction.

In order to understand how photography as a medium can be applied to tell a story we need to understand the differences between narrative and story and how editing, sequencing and design is intrinsic to this process.

Often people tend to think of narrative and story as the same thing. In photography that is no exception. Jörg M. Colberg, a photographer, teacher and editor of Conscientious Photo Magazine (online blog dedicated to contemporary fine-art photography) has written extensively about narrative in photography. For you to gain a better understanding of the differences between narrative and story when we think about it in relation to making a photobook (which is your main outcome in your Personal Study later in the academic year) or in your current task of making a photo-zine you NEED TO READ his two blog posts; Photography and Narrative (part 1) and Photography and Narrative (part 2).

According to Dictionary.com, narrative can be:

In Colberg’s view;

‘Those three options really aren’t the same at all. A photobook’s story is not the same as the book itself…. What I tend to find is that many photographers use the term narrative in the sense of it being the same as story (option 1), but what they mean is that it is the way the story is told (Option 3).’

He continues:

‘This is because it will contain a set of photographs that are being presented in a very specific way: there is an edit, a sequence, and very specific decisions about design and production were (hopefully) being made. As I’m trying to explain in the following, the edit and sequence (and to a lesser extent design and production) form a specific narrative that, in turn, might or might not produce or allude to a story. How to approach this then?’

When Colin Pantall made his book, All Quiet on the Homefront about his daughter growing up and becoming a father he wrote about the process of making it on his Blog here: Identifying the Story: Sequencing isn’t narrative

In Pantall’s experience narrative isn’t just sequencing a set images that flows together nicely. He says:

‘In photobooks there are so many elements used in editing, sequencing and creating a narrative. It’s really difficult. For All Quiet on the Home Front, we went through the lot of them. Sequencing by chronology, geography, family, resemblance, art history, season, colour, form, tone, flora, expression, dress, climate, mood, symbolism, material, and so on. The sequencing was a gradual process that was embedded into the editing with voice, mode, person, text, the basic best picture edit and much more besides.’

In his view identifying the story first and being able to communicate it in three words is essential.

‘You can sequence in a multitude of ways in other words. But none of that made a narrative. What made the narrative was actually identifying what the story was about. Do that and then you can create all the structures through which the story can flow – and that, structures plus story, creates the narrative.’

For photographer, writer and lecturer, Lewis Bush; ‘narrative are things that exists within stories.’ In his article, Storytelling: A Poverty of Theory, Bush gives different reasons why photography as a medium does not have an established theory on narrative like cinema or literature. He also wonders why photographers often refer to themselves as storytellers but have little understanding of the differences between story and narrative when applied to photography.

‘One story can spawn many narratives, a fact that, in contrast to photography, is well understood in literature and cinema….when I say ‘I’m going to tell you a story’ I actually tell you a narrative of that story.’

Bush cites an example in cinema, Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon where multiple narratives are presented on screen of a murder, that may or may not have happened.

In photography today Bush reminds us;

‘it is well understand that single images are not reality, they are a representation of it.’ Similarly, a series of images put together in a fragmentary and incomplete order is ‘a record of something [that] are always a narrative of a story or event, never a full reflection of the thing itself’.

Lewis Bush gives examples of books that he has made which provides different narrative structure, from very linear to experimental. For example: Books that rework the narratives of other books, books which can be read back to front and front to back, and books with no fixed narrative at all. I’m currently working on one with a narrative which travels forwards and backwards in time simultaneously, and another a book which will not actually exist, and so I suppose neither will its narrative.

In a follow article: ‘Photographic Narrative: Between Cinema and Novel‘ Lewis Bush cites different examples from both cinema, literature and photography and identity each mediums different strengths and weaknesses.

In Bush’s view, photography’s narrative strength is;

‘It’s sheer power of description.’ A single photograph can depict a scene with a verisimilitude which pages of written account would still fail to capture. It is this quality which led photography to be first employed for practices like crime scene photography, in place of the unreliable memory and incomplete notes that had previously been relied upon.

Conversely photography also has many weaknesses, such as explaining things. Bush cites German theatre parctitioner and playwright Bertol Brecht who wrote, a photograph of a factory tells us what a factory looks like, but it tells us very little about the relationships that underlie it.

Bush also references Roland Barthes , whose seminal book, Camera Lucida,(1980) is a bedrock of photographic theory, especially, the relationship between photography and memory, photograph and death. He describes reading a sentences where Barthes, ‘characterised photographs as things which were somewhere “between cinema and novel”.

Bush then outlines traits and similarities for storytelling between photography and cinema, photography and literature and provides a number of examples which we will have a closer look at below.

Chris Marker: La Jétte

Chris Marker, (1921-2012) was a French filmmaker, poet, novelist, photographer, editor and multi-media artist who has been challenging moviegoers, philosophers, and himself for years with his complex queries about time, memory, and the rapid advancement of life on this planet. Marker’s La Jetée is one of the most influential, radical science-fiction films ever made, a tale of time travel. What makes the film interesting for the purposes of this discussion, is that while in editing terms it uses the language of cinema to construct its narrative effect, it is composed entirely of still images showing images from the featureless dark of the underground caverns of future Paris, to the intensely detailed views across the ruined city, and the juxtaposition of destroyed buildings with the spire of the Eiffel Tower. You can read more here about the meaning of the film and it is available on Vimeo here in its entirety (29 mins)

Mark Cousins: Atomic, Living in Dread and Promise

A narrative can also be made constructed entirely of archive footage as in Atomic, Living in Dread and Promise, a film that shows impressionistic kaleidoscope of our nuclear times – protest marches, Cold War sabre-rattling, Chernobyl and Fukishima – but also the sublime beauty of the atomic world, and how x-rays and MRI scans have improved human lives. The nuclear age has been a nightmare, but dreamlike too. Made by director and film critic, Mark Cousins and featuring original music score by Mogwai, it was first broadcast on BBC4 as part of Storyville documentary. Your can read a Q&A with Cousins’ here where he discusses the making of the film.

Christopher Nolan: Memento

Memento is a 2000 American neo-noir psychological thriller film written and directed by Christopher Nolan. Guy Pearce stars as a man who, as a result of an injury, has anterograde amnesia (the inability to form new memories) and has short-term memory loss approximately every fifteen minutes. He is searching for the people who attacked him and killed his wife, using an intricate system of Polaroid photographs and tattoos to track information he cannot remember.

The film is presented as two different sequences of scenes interspersed during the film: a series in black-and-white that is shown chronologically, and a series of color sequences shown in reverse order (simulating for the audience the mental state of the protagonist). The two sequences meet at the end of the film, producing one complete and cohesive narrative

Telling a story in reverse can be an interesting way to construct a narrative. Both cinema and literature are good at jumping between different time modes, past, present and future. Moving image and sound can enhance these different temporal shifts and written language is good and transporting your imagination from one time zone to another. Photography is mute but different strategies can be employed such as changing from colour to monochrome suggesting a different time or a different set of images. Using old photographs from archives, or found imagery can add complexity too, and including words can support a sequence of images, or add tension between the visual and the textual adding other elements to a photographic narrative.

Memento: Narrative and Postmodernism is also being looked at in Media Studies and if you are studying this subject make sure you include knowledge and understanding learned. Adopting a inter-disciplinary approach to your work is advantageous and being able to use theory and/ or context from other subjects will add value to your overall quality of your work and potentially achieve higher marks.

Theorists like Sergei Eisenstein, D.W Griffiths, Lev Kuleshov, Jean Epstein, John Grierson (also the coiner of the term ‘documentary’), Dziga Vertov, Andre Bazin, and Siegfried Kracauer went into sometimes painful detail to articulate theories about how various film and editing combinations created different forms of meaning. Many of these ideas remain surprisingly robust and useful a century later, and remain the bedrock of much of the theory taught to film students. Let’s look at some narrative structures and film editing techniques that are used in cinema.

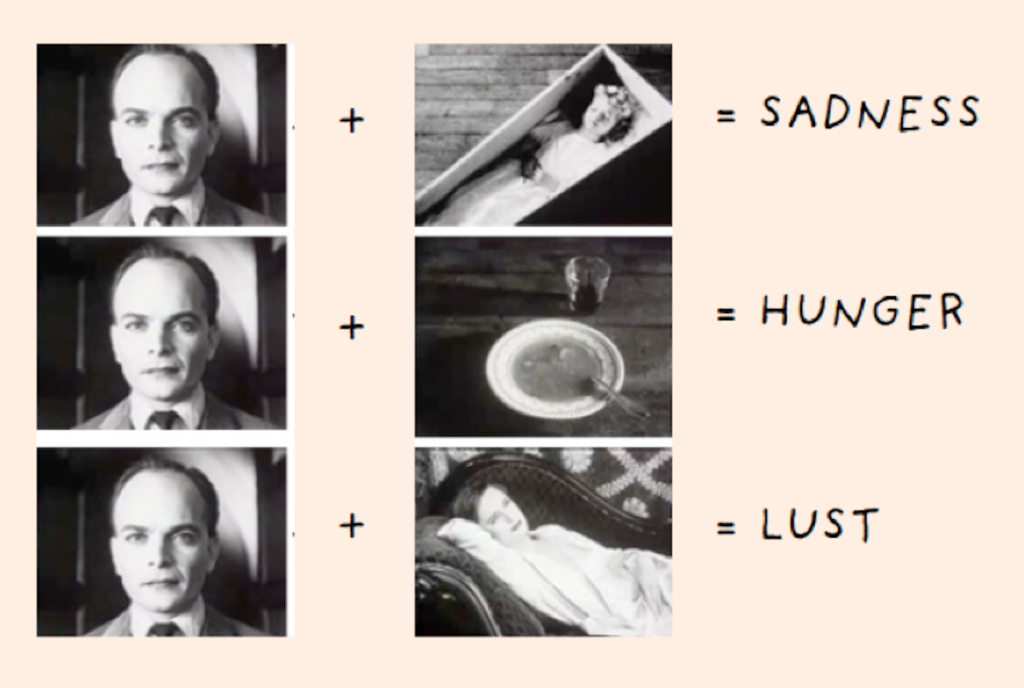

The Kuleshov effect is a film editing (montage) effect demonstrated by Soviet filmmaker Lev Kuleshov in the 1910s and 1920s. It is a mental phenomenon by which viewers derive more meaning from the interaction of two sequential shots than from a single shot in isolation. Through this phenomenon we can suggest meaning and manipulate space, as well as time.

Kuleshov edited a short film in which a shot of the expressionless face of Tsarist matinee idol Ivan Mosjoukine was alternated with various other shots (a bowl of soup, a girl in a coffin, a woman on a divan). The film was shown to an audience who believed that the expression on Mosjoukine’s face was different each time he appeared, depending on whether he was “looking at” the bowl of soup, the girl in the coffin, or the woman on the divan, showing an expression of hunger, grief, or desire, respectively. The footage of Mosjoukine was actually the same shot each time.

Kuleshov used the experiment to indicate the usefulness and effectiveness of film editing. The implication is that viewers brought their own emotional reactions to this sequence of images, and then moreover attributed those reactions to the actor, investing his impassive face with their own feelings. Kuleshov believed this, along with montage, had to be the basis of cinema as an independent art form.

For more details see Dr McKinlay’s blog on Narrative in Cinema and The Language of Moving Image which look more specifically at some of the conventions and key terminology associated with moving image (film, TV, adverts, animations, installations and other moving image products.)

Let’s explore some examples of images used in photo-essays and photobooks and see if we can identify the story as well as examine how narrative is constructed through careful editing, sequencing and design.

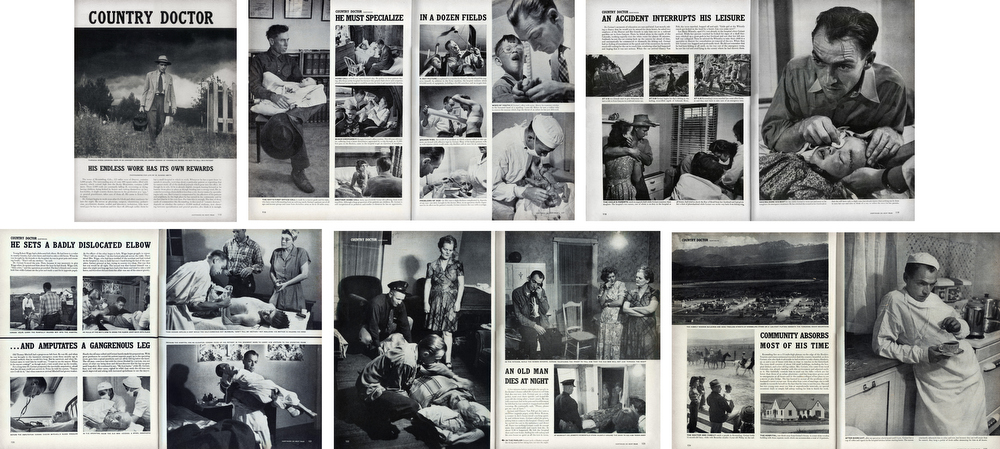

W. Eugene Smith: Country Doctor

PHOTO-ESSAY: The life of a country doctor in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains

“A photo is a small voice, at best, but sometimes – just sometimes – one photograph or a group of them can lure our senses into awareness. Much depends upon the viewer; in some, photographs can summon enough emotion to be a catalyst to thought”

W. Eugne Smith

W. Eugene Smith compared his mode of working to that of a playwright; the powerful narrative structures of his photo essays set a new benchmark for the genre. His series, The Country Doctor, shot on assignment for Life Magazine in 1948, documents the everyday life of Dr Ernest Guy Ceriani, a GP tasked with providing 24-hour medical care to over 2,000 people in the small town of Kremmling, in the Rocky Mountains. The story was important at the time for drawing attention to the national shortage of country doctors and the impact of this on remote communities. Today the photoessay is widely regarded as representing a definitive moment in the history of photojournalism.

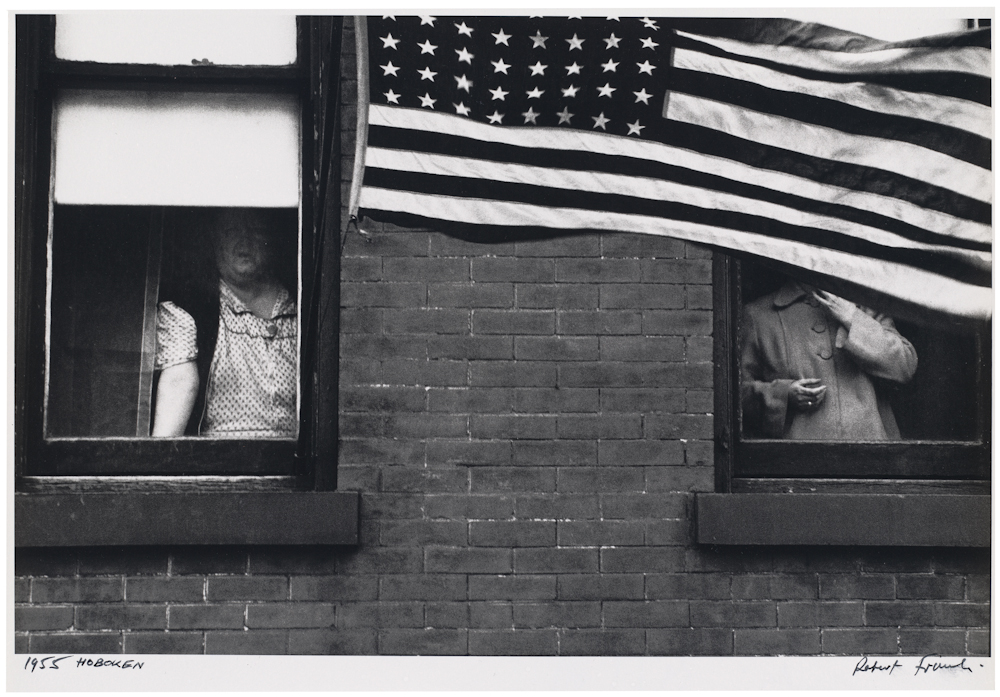

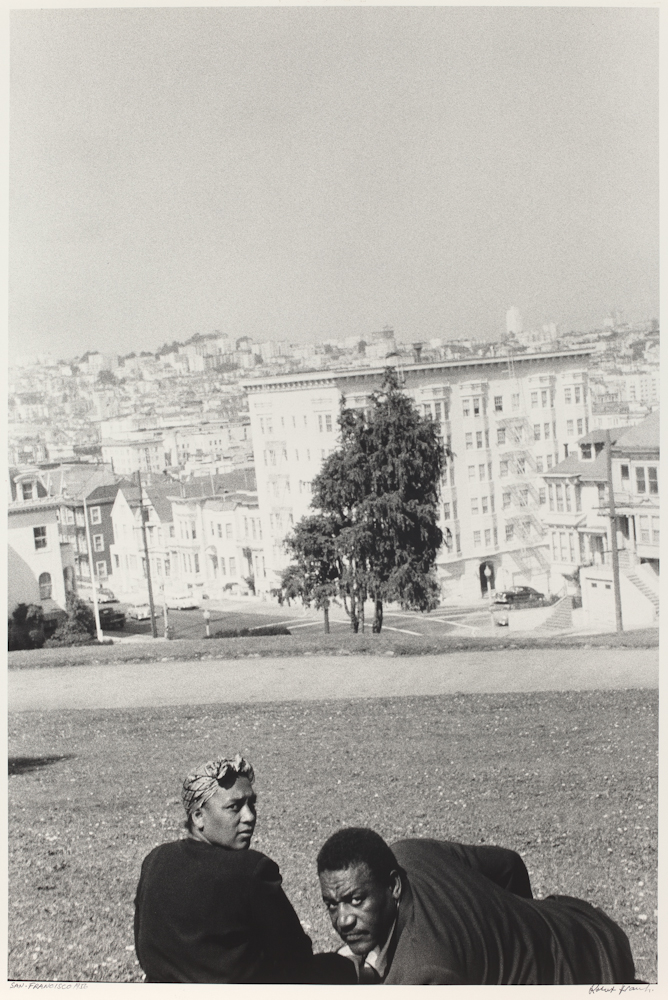

Robert Frank: The Americans

In October of 1958, French publisher Robert Delpire released Les Américains in Paris. The following year Grove Press published The Americans in New York with an introduction by American writer, Jack Kerouac (the book was released in January 1960).

Like Frank’s earlier books, the sequence of 83 pictures in The Americans is non-narrative and nonlinear; instead it uses thematic, formal, conceptual and linguistic devices to link the photographs. The Americans displays a deliberate structure, an emphatic narrator, and what Frank called a ‘distinct and intense order’ that amplified and tempered the individual pictures.

Although not immediately evident, The Americans is constructed in four sections. Each begins with a picture of an American flag and proceeds with a rhythm based on the interplay between motion and stasis, the presence and absence of people, observers and those being observed. The book as a whole explores the American people—black and white, military and civilian, urban and rural, poor and middle class—as they gather in drugstores and diners, meet on city streets, mourn at funerals, and congregate in and around cars. With piercing vision, poetic insight, and distinct photographic style, Frank reveals the politics, alienation, power, and injustice at play just beneath the surface of his adopted country.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/videos/category/arts-culture/inside-robert-franks-the-americans/

Since its original publication, The Americans has appeared in numerous editions and has been translated into several languages. The cropping of images has varied slightly over the years, but their order has remained intact, as have the titles and Kerouac’s introductory text. The book, fiercely debated in the first years following its release, has made an indelible mark on American culture and changed the course of 20th-century photography. Read article by Sean O’Hagan in The Guardian

Rita Puig Serra Costa: Where Mimosa Bloom

Dealing with the grief that the photographer suffered following the death of her mother, Where Mimosa Bloom by Rita Puig Serra Costatakes the form of an extended farewell letter; with photography skillfully used to present a visual eulogy or panegyric. This grief memoir about the loss of her mother is part meditative photo essay, part family biography and part personal message to her mother. These elements combine to form a fascinating and intriguing discourse on love, loss and sorrow.

“Where Mimosa Bloom” is the result of over two years work spent collecting and curating materials and taking photographs of places, objects and people that played a significant role in her relationship to her mother. Rita Puig Serra Costa skillfully avoids the dangerous lure of grief’s self-pity, isolationism, world-scorn and vanity. The resonance of “Where Mimosa Bloom” comes from all it doesn’t say, as well as all that it does; from the depth of love we infer from the desert of grief. Despite E.M.Forster’s words – “One death may explain itself, but it throws no light upon another” – Rita Puig Serra Costa proves that some aspects of grief are universal, or can be made so through the honesty and precision with which they are articulated.

Yoshikatsu Fujii: Red Strings

I received a text message. “Today, our divorce was finalized.” The message from my mother was written simply, even though she usually sends me messages with many pictures and symbols. I remember that I didn’t feel any particular emotion, except that the time had come. Because my parents continued to live apart in the same house for a long time, their relationship gently came to an end over the years. It was no wonder that a draft blowing between the two could completely break the family at any time.

In Japan, legend has it that a man and woman who are predestined to meet have been tied at the little finger by an invisible red string since the time they were born. Unfortunately, the red string tying my parents undone, broke, or perhaps was never even tied to begin with. But if the two had never met, I would never have been born into this world. If anything, you might say that there is an unbreakable red string of fate between parent and child.

Before long, I found myself thinking about the relationship between my parents and . How many days could I see my parents living far away? What if I couldn’t see them anymore? Since I couldn’t help feeling extremely anxious about it, I was driven to visit my parents’ house many times. Every day I engage in awkward conversation with my parents, as if in a scene in their daily lives. I adapt myself to them, and they shift their attitude toward me. We do not give way entirely to the other side, but rather meet halfway. Indeed family problems remain unresolved, although sometimes we tell allegorical stories and share feelings. It means a lot to us that our perspectives have changed with communication.

My family will probably never be all together again. But I feel without a doubt that there is proof inside of each of us that we once lived together. To ensure that the red string that ties my family together does not come undone, I want to reel it in and tie it tight.

Narrative is essentially the way a story is told. For example you can tell different narratives of the same story. It is a very subjective process and there is no right or wrong. Whether or not your photographic story is any good is another matter.

An analogy: if you witnessed a road accident and the police arrived to take statements from witnesses. Your version of events would be different to that of other witnesses or bystanders. They are both ‘true’ to what you saw and they both tell a different narrative depending on where you were in relation to the event, your point of view and how you remembered the event as it happened.

Narrative is constructed when you begin to create relationships between images (and/or text) and present more than two images together. Your selection of images (editing) and the order of how these images appear on the pages (sequencing) contributes significantly to the construction of the narrative. So too, does the structure and design of the photo-zine or photobook.

However, it is essential that you identity what your story is first before considering how you wish to tell it. Planning and research are also essential to understanding your subject and there are steps you can take in order to make it successful. Once you have considered the points made between the differences in narrative and story, write the following:

PLANNING: Write a specification that provide an interpretation and plan of how you intend to explore A Love Story. This must include at least 3 photoshoots you will be doing in the next 2-3 weeks (these could include photo-assignments). How do you want your images to look and feel like? Include visual references to artists/photographers in terms of style, approach, intentions, aesthetics concept and outcome. Remember the final outcome is a 16 page photo-zine so you will need to edit a final series of 12-16 images that sequenced together as a set forms a narrative that visualises your love story.

STORY: What is your love story?

Describe in:

NARRATIVE: How will you tell your story?

AUDIENCE: Who is it for?

Most image makers tend to overlook the experience of the viewer. Considering who your audience is and how they may engage with your photo-zine is important factor when you are designing/ making it.

A few photo book dealing with memory, loss and love

Yury Toroptsov: Deleted Scene

On a mission to photograph the invisible, with Deleted Scene photographer Yury Toroptsov takes us to Eastern Siberia in a unique story of pursuit along intermingling lines that form a complex labyrinth. His introspective journey in search of a father gone too soon crosses that of Akira Kurosawa who, in 1974, came to visit and film that same place where lived the hunter Dersu Uzala.

Yury Toroptsov is not indifferent to the parallels between hunting and photography, which the common vocabulary makes clear. Archival documents, old photographs, views of the timeless taiga or of contemporary Siberia, fragments or deleted scenes are arranged here as elements of a narrative. They come as clues or pebbles dropped on the edge of an invisible path where the viewer is invited to lose himself and the hunter is encouraged to continue his relentless pursuit.

Mayumi Suzuki: The Restoration Will

My parents, who a owned photo studio, went missing after the 2011 tsunami. Our house was destroyed. It was a place for working, but also for living. I grew up there. After the disaster, I found my father’s lens, portfolio, and our family album buried in the mud and the rubble.

One day, I tried to take a landscape photo with my father’s muddy lens. The image came out dark and blurry, like a view of the deceased. Through taking it, I felt I could connect this world with that world. I felt like I could have a conversation with my parents, though in fact that is impossible.

The family snapshots I found were washed white, the images disappearing. The portraits taken by my father were stained, discolored. These scars are similar to the damage seen in my town, similar to my memories which I am slowly losing.

I hope to retain my memory and my family history through this book. By arranging these photos, I have attempted to reproduce it.

Dragana Jurisic’s YU: The Lost Country

Yugoslavia fell apart in 1991. With the disappearance of the country, at least one million five hundred thousand Yugoslavs vanished, like the citizens of Atlantis, into the realm of imaginary places and people. Today, in the countries that came into being after Yugoslavia’s disintegration, there is a total denial of the Yugoslav identity.

“There proceeds steadily from that place a stream of events which are a source of danger to me,” wrote the Anglo-Irish writer, Rebecca West in 1937. “That place” was Yugoslavia, the country in which I was born. Realizing that to know nothing of an area “which threatened her safety” was “a calamity”, she embarked on a journey through Yugoslavia. The result was Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. Initially intended as “a snap book” it spiraled into half a million words, a portrait not just of Yugoslavia, but also of Europe on the brink of the Second World War, and widely regarded as one of the masterpieces of the 20th century.

At Easter 2011, I started retracing Westʼs journey and re-interpreting her masterpiece by using photography and text, in attempt to re-live my experience of Yugoslavia and to re-examine the conflicting emotions and memories of the country that was.

Jacob Aue Sobol: Sabina

In 1999, Jacob Aue Sobol went to live in the settlement of Tiniteqilaaq, Greenland, where he lived the life of a fisherman and hunter with his Greenlandic girlfriend Sabine and her family. Taken over three years Sobol’s book records, in photographs and narratives, his encounter with Sabine and their life on the east coast.

Photographer Jacob Aue Sobol reflects on the three years he spent in Greenland and the traveling he did there. While his first trip was focused on documenting the culture, his second trip revolved around his girlfriend Sabine, who later became the subject of a series of photographs.

Laia Abril: The Epilogue’

‘The Epilogue’ is the book about the story of the Robinson family – and the aftermath suffered in losing their 26 year old daughter to bulimia. Working closely with the family Laia Abril reconstructs Cammy’s life telling her story through flashbacks – memories, testimonies, objects, letters, places and images. The Epilogue gives voice to the suffering of the family, the indirect victims of ‘eating disorders’, the unwilling eyewitnesses of a very painful degeneration. Laia Abril shows us the dilemmas and struggles confronted by many young girls; the problems families face in dealing with guilt and the grieving process; the frustration of close friends and the dark ghosts of this deadliest of illnesses; all blended together in the bittersweet act of remembering a loved one. Read more here on Laia Abril’s website

AUDIENCE: Most image makers tend to overlook the experience of the viewer. Considering who your audience is and how they may engage with your photo-zine is important factor when you are designing/ making it.

Students past responses to the theme of love, friendship, family etc.

Niah Da Costa: Espera

For my photo book, the main theme was intimacy and young love. I wanted to explore my relationship with my boyfriend and show a series of different styles of images. I called this photo book “Espera” which means to wait in Portuguese, as this word (besides love) is a word that both Jack and I use frequently. Read more on her BLOG here.

Amy Low: Nothing can get between us

A photo-book which is based on specific people in my life and what makes them an individual, I want this to also center around the theme of youth culture. Each picture/section of my book is about one person and their features/interests and things that make them who they are. I also plan to have pictures which break theme in the book to act as a barrier between each portrait. Read more on her BLOG here.

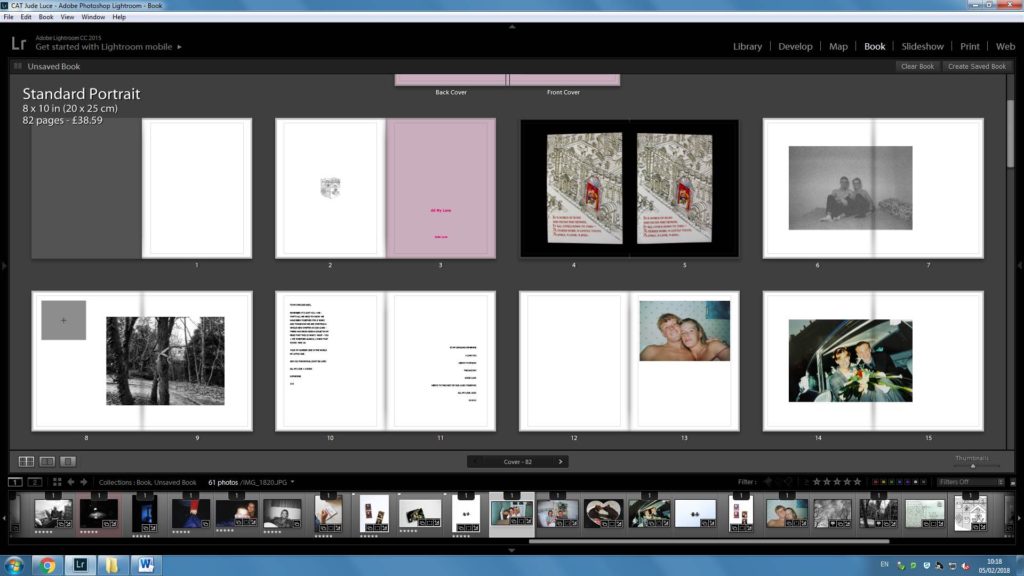

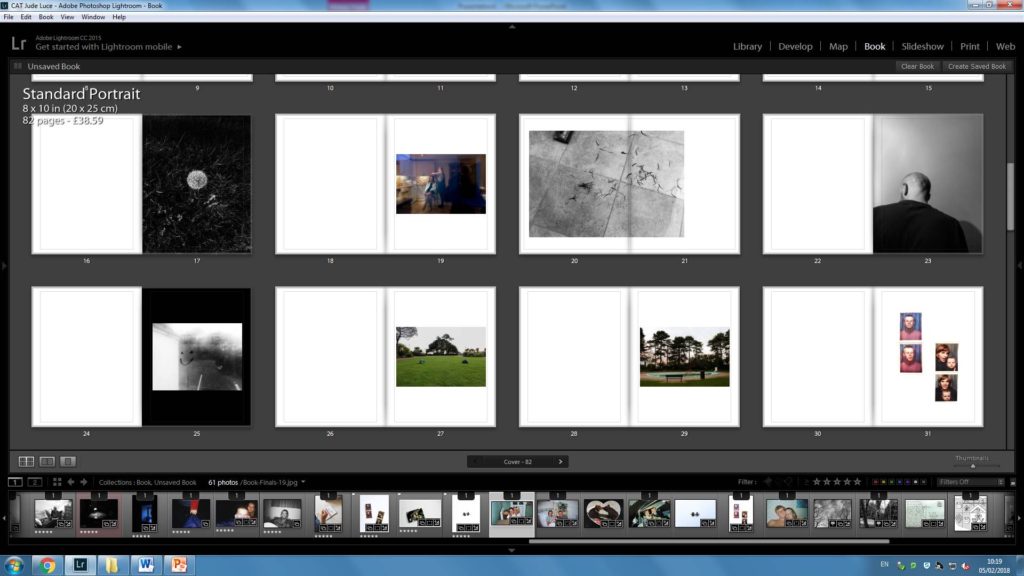

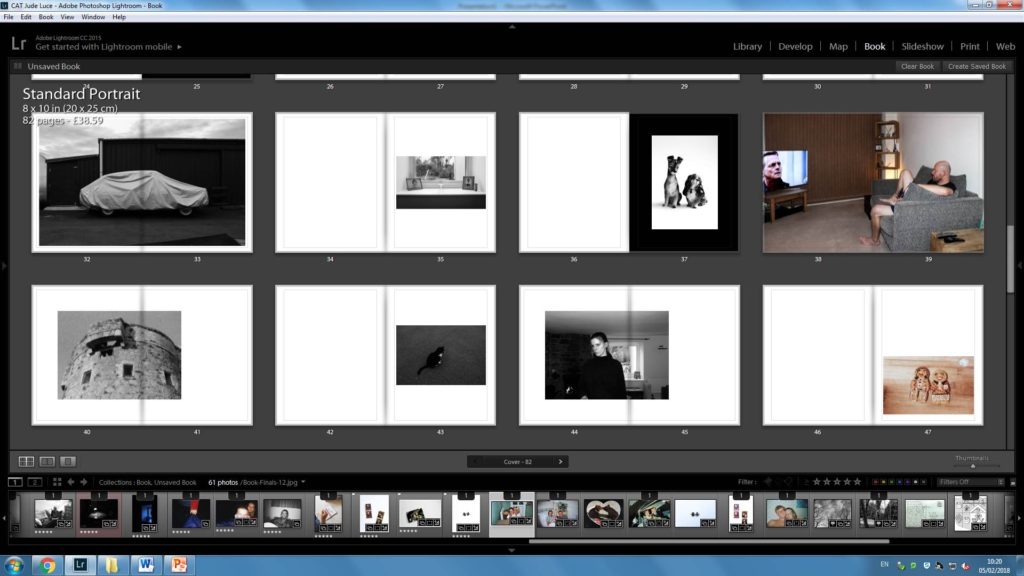

Jude Luce: All My Love

My plan for my photo book is to produce a detailed and insightful exploration into my family life, with me centered within the middle. This is the running theme throughout and I hope to show it through poetic, still images of landscapes or objects which may have no direct meaning at its face value but has a deeper meaning once inferred. As well, the portraits in my project are intended to be collaborative and intimate to show the relationships I hold with the people in my life but the portraits are intended to show the emotion of each being as well. I have contrasted yet shown the similarities of my mum and dad’s relationship when they were together to that of my relationship with Lucy now and the overall look I hope to achieve is that of a fun, vibrant, light-hearted but quite solemn and sombre image-based diary about how I am still developing through the events if life and the attachments I have built from the event which shaped my life – my mum and dad’s divorce. I want their to be an obvious existence of the theme of attachment but also an underlying theme of detachment. Although these themes are the main focus for my book, they are underlying themes which are subtly hinted at every now and then by a sequence which develops upon the understanding of love. Memory is fragile and I use this notion as a driving force for my project made up of diaristic photographs, which, when come together, create an album of moments in time which in-turn lend themselves to never be forgotten. I have attempted not to avoid the subject of my mum and dad’s divorce but felt it easier to express this and my feelings towards it through other subject matter, being my relationship with my girlfriend and the other people in my life, such as my individual relationships with my mum and dad and how I view them in solitary opposition to one another.

Read more on Jude’s BLOG

link to photobook, All My Love

Cerian Mason: Untitled

I produce a large amount of documentary style images revolving around the more shadowed teenage social life. This involves being in a lot of places we shouldn’t be, drinking too much and probably a little more nudity that this blog is ready for. Below is a selection of my project work over the last few weeks presenting a range of locations – from abandoned hotels to out of hours nightclubs – featuring my friends being strange and causing trouble. There are some clear trends in the image I create such as the selective palettes and tight range of colours and the positioning of characters – these images were not directed at all though the figures were of course aware I was photographing them. This photobook was made using bookwright software and will be printed as a portrait A4 project. Many of the design ideas for this projects are inspired from artists and graphic designers I have studied over the last two years such as Lotta Nieminen. Studying the graphic designer’s personal projects. I took particular notice of the image layouts and use of overlapping text. There is a carefully controlled colour palette and minimalistic design which aids the presentation of images in such a publication. Benjamin Koh’s project work again has a strong graphic theme which uses a muted colour palette to emphasize the continued sense of photographic narrative. His pages tend to be uncluttered and minimal which draws attention to the graphic images in each of the carefully constructed double-page spreads. These elements were crucial to my own work, ensuring that images would be easily visible and clearly presented.

Read more here on his BLOG

Link to his book: The Getaway

Gio Rios: Home Sweet Home?

In terms of my title, I called my book ‘home sweet home?’. This is of course a common household saying, that I have added a question mark to. Due to the fact that my home life is fairly broken and has been on and off my entire life, which makes it far from ‘sweet’. On the first page within my book I write the quote ‘family means no one gets left behind or forgotten’. This is controversial from the start, as my farther had done exactly this from my birth, which is ultimately what stems my thoughts and feelings towards a lot of my family life and the reasons for the decisions made within this book.

Read more here on his BLOG

Here I feature a stand alone image of an ultrasound of me. This is used to imply that I am the center of this book and that this is my own representation. The inclusion of juxtaposing images, put alongside one another, help to emphasise my emotions towards certain characters within my book.

My granddad is someone who has consistently been in and out of my life, throughout my upbringing. Therefore I feature him alongside a set of spiraling stairs to imply that he has spiraled out of my life.

Link to his book: Home Sweet Home?

Rochelle Merhet: Ryan

The first step I took to my project inspired by the work of the artists I have studied and discussed was look at my own archived family photographs. I have a huge selection taken by my parents featuring me and my brother, many appeared very informal depicting me and my brother playing and laughing at each other, which gave the ability to see the relationship between me and my brother and how it has developed. Much like any family album, these photographs share a very personal importance to me. I wanted to use photographs that depicted who I was as well as my brother in my book as a way of a candid reflection of what my childhood was like and how I felt about it. Similar to the work of Carolle Benitah I wanted to make physical alterations to the photographs to further explore the notion of nostalgia, memories and the relationships between family members, in particular between me and my brother. I wanted use their project as a way to further understand myself through the use of memories and photographs to build and develop and understanding of who me and my brother are today and in particular our differences which are created from the notion of ‘nature and nurture’.

Read more here on her BLOG

Link to her book: Ryan

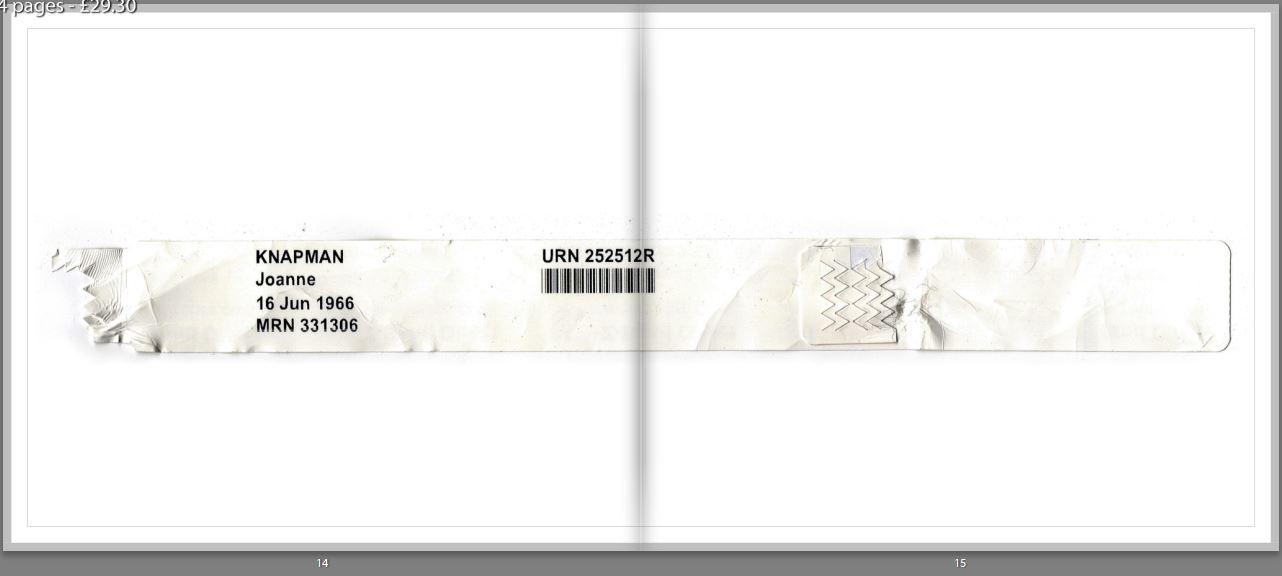

Matthew Knapman: Is that My Blue Butterfly?

The research of both these artists informed and influenced my personal project, which focused on the life of my mother who is currently diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. She was originally diagnosed with breast cancer in Easter 2014, but when the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, it is called metastatic cancer. The liver, lungs, lymph nodes, and bones are common areas of spread of metastasis. Using art and physical materials, I wanted to draw into and edit the photographs I take in order to illustrate my emotions and what my mother is going through. The physical art would be a visual guide to the audience, telling a story regarding the illness. This is something that I was excited to do, given my passion and abilities in art and design. I can draw, scratch or edit the photograph using chemicals and other kinds of destructive methods. This can demonstrate some kind of investigation into the relationship between traditional art and Photography as mediums. This is something that I touched upon for my AS project.

Read more here on his BLOG

Link to his book: Is That My Blue Butterfly?

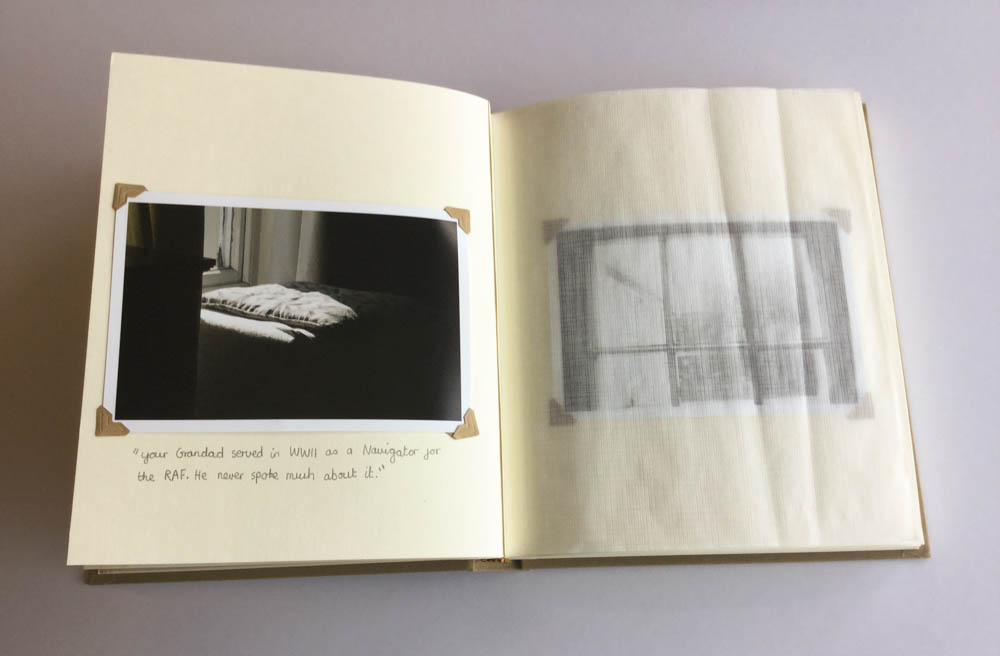

Max Le Feuvre: Untitled

My photo-book is based around my Grandfather. He died 30 years ago and so I never got the chance to meet him. I wanted therefore to find out more about him and develop an understanding of what he may have been like if I had got to know him. This project was therefore very much about exploring and investigating the theme of absence, a story based around someone who is no directly part of it. I photographed off and on for 9 months to create this project, re-tracing my Grandfather’s steps and using photography to express my findings. Archival resources in particular have played a huge part in my project, especially through the access I have had from the Société Jersiaise Photographic Archives, and the resources I have found play as much a part in this story as does my own responses. I wanted to make my images and narrative feel as simplistic and personal as possible and so I constructed my photo-book by hand, I style I believe gives my work a quirky, old-fashioned feel.

Read more here on his blog:

https://hautlieucreative.co.uk/photo16a2/author/mlefeuvre05/

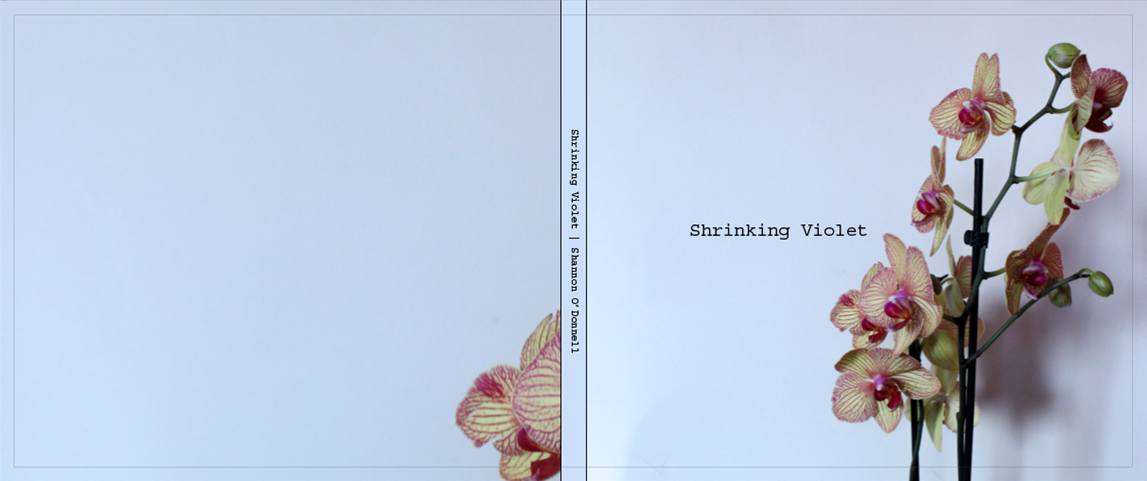

Shannon O’Donnell: Shrinking Violet

Shrinking Violet stemmed from a short film that I created as part of my project of my mother. I made a film based around an interview that I did with my mum and made it up of archival images as well as documenting her everyday life. Part of the interview sparked my interest when she said ‘I’m not one of those shrinking violets in the work place’. This caught my attention as I see her role as simply doing what is expected of her, something that I want to challenge through my photographic work. This brought on the idea for creating a parody shoot where I dress as a persona, similar to my mum, and pose around the house mimicking the role I see my mum portray. I wanted this photo book to embody the traditional role of women our society perceives and for spectators to view the images I have created to recognise themselves, their mothers, their sisters and their wives. Gender defines everyone and, at times, can be limiting. It makes us feel that we need to belong and conform to the expectations placed on us at birth solely on whether we were born male or female.

Explore research, ideas, experimentation on the her blog:

https://hautlieucreative.co.uk/photo16a2/author/sodonnell05/

Watch her film below about feminism, her mother and her role in the family. This film was the starting point for her photographs above by re-staging herself as a domisticated female

link to her photo book: Shrinking Violet

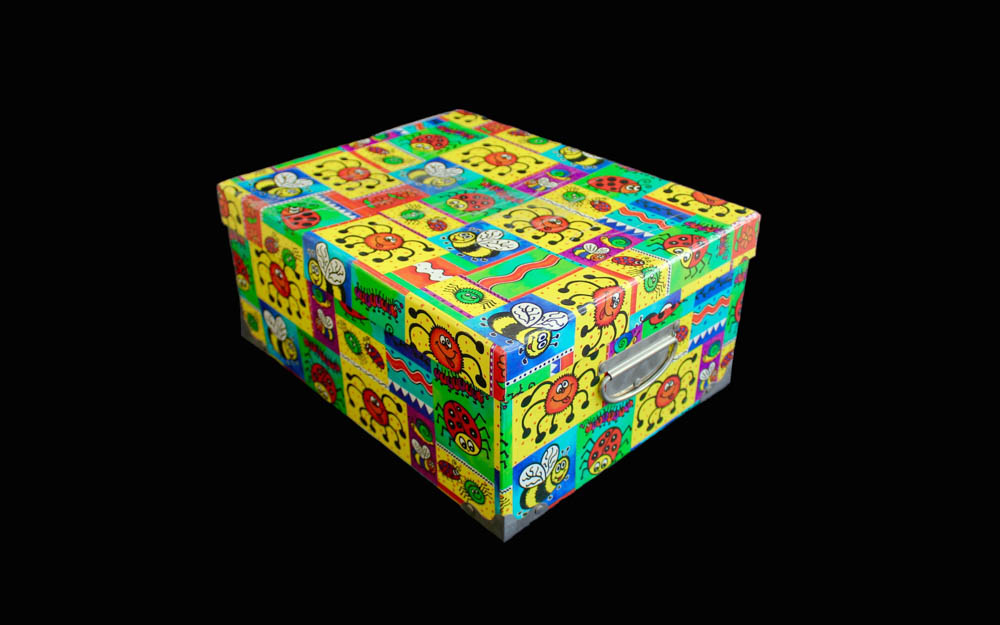

Jemma Hosegood: The Memory Box

“Good friends make you face the truth about yourself and you do the same for them, as painful, or as pleasurable, as the truth may be.” – Corinne Day

An autobiography is an account of the life of a person written by that person. In other words, it is the story that a person wrote about themselves. My inspiration for this study came from memories that are forgotten, and the ‘things’ that re-jog our brains to remember them. These could be objects from a childhood collection box or a set of images from a blurry holiday. For this piece of work I attempted to join two ways of memory revival into a book as well as a layout presenting some of my final images.

Read her blog:

https://hautlieucreative.co.uk/photo16a2/author/jhosegood05/

Link to her photo book: Memory Box

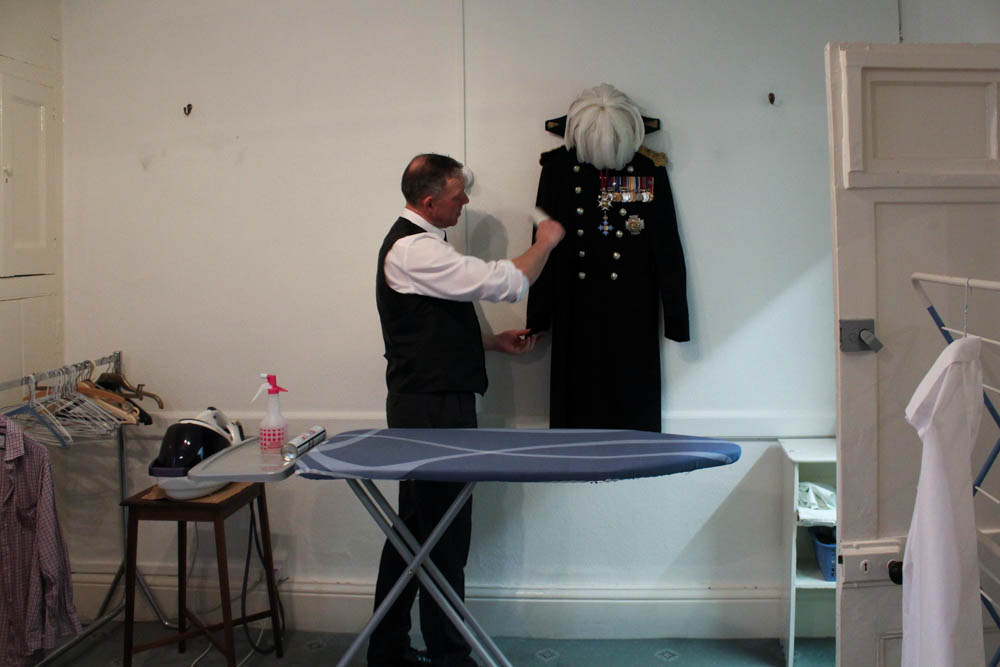

Sian Cumming: The ButlerAs a photographer, it is important for me to express details about my life to almost create a biography through photographs. I chose to use my dad for my project as his job has impacted my life since day 1. My dad is the Butler for the Lieutenant Governor of Jersey and has enabled me to have an insight into the life of royalty. My dad’s responsibilities are; ensuring the house events run smoothly, he also manages the house staff and liaises with his Excellency and Lady Mc Cole for all their requirements. I have lived in the grounds of Government House all my life and have truly honoured living here. Our tight community has really impacted my life and the way I am, as I also work as a waitress for Government House functions, I have been taught the type of service required for the Governor and his guests by my Dad himself. It was an honour to follow the footsteps of my dad and what he does at work and for the Governor to allow me take photographs of him off duty was a privilege in itself. To me, family is the most important aspect in life, it’s the root to our personality. Family is the single most important influence in a child’s life. From your first moments of life, you depend on parents and family to protect and provide for your needs. They form your first relationships with other people and are your role models throughout life. Researching into the way different photographs express the notion of home was truly inspiring and made me want to produce something that shows how my life has been

Link to her book: The Butler

Your task is to produce a 16-page zine based around A Love Story.

Your love story may be real, for example it could be based around a love story in your family, such as grandparents, parents, siblings or other relatives (uncles, aunties, cousins) whose stories about love (both finding it and loosing it) that you may have been told around dinner tables or family gatherings. Stories that might be true or false, or based on facts that over time has been fictionalised and become family lore or myth.

Love can also be found among friends or take inspiration from personal experiences of teenage love. A love story could also be about unrequited love, or falling out of love with someone. However, a love story does not have to include romance. People love each other without physically desiring one another. It could be felt beyond the physical to include a spiritual connection. Some people talk about having found a soul mate. What does this actually mean? How could you translate this into a visual narrative and begin to make photographic responses?

A love story could also be about someone ‘loving’ one particular thing or aspects of their life, such as a love for an animal, hobby, sport or nature.

Francis Foot started to have an interest in photography not long after he became a gas fitter as his main profession. He had a fascination with phonographs and gramophones and soon learnt that this could be his new and improved career. His family bought a shop in Pitt Street, this is where Foot began this career as a photographer and his father and mother helped him make money by selling gramophones, records and other wares in Dumaresq Street.

Foot and his family prospered through keeping the HMV franchise for Jersey with their famous logo which was a painted that was created in 1899 by Francis Barraud. The painting of the dog Nipper listening to a cylinder phonograph still remains on the Dumaresq Street wall today.

Due to the success from the HMV franchise, as well as selling his photographs to be published on postcards, Foot managed to take over another shop in Pitt Street, where he carried on selling records in the 1950s and 60s when they were made from vinyl.

Alec Soth is a photographer born and based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, famous for his ‘documentary style’ photographs which where influenced by Walker Evans traditional American photography. Soth is interested in and focuses on the relationship between narrative and metaphor, and draws many comparisons to literature, although, he believes photography to be more “like poetry than writing a novel.” He has published over twenty-five books, some of them are Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004), NIAGARA (2006), Broken Manual (2010), and I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating (2019).

In an interview with Hanya Yanagihara in early 2019 for the New York Times magazine, Soth begins to talk about how and why he takes his photographs the way he does, explaining that “When I started this project, my only intention was to spend time with another person in a room, any room. But after I photographed Anna Halprin, I decided it should be in the subject’s home. This makes them more comfortable. It’s also more stuff to help reveal what might be going on inside of them”.

A Conversation With Alec Soth About Art and Doubt- The New York Times:

His second project NIAGARA was an exploration of ‘love‘ and long term relationships and commitment, which I can directly link to my theme of love in my blog so far. One of the main points that Soth has repeated thought various interviews is that he was interested in making the focus and person he was photographing comfortable, by being in a familiar environment that they love and cherish.

This is one of my favourite of Soth’s photographs. It shows an old woman, who we can assume to be Anna from Kentfield in California sitting comfortable in a chair in a beautiful seating area. The lighting is clearly a natural daylight coming though the windows. I think that the image Soth’s taken is very clever, as the woman home is obviously filled with plans and vines, and the fact that Soth has taken the image from outside has mean that a delicate reflection of greenery and sunlight is placed around the frame of the photograph. In the centre of the image is a full length body shot of Anna, sitting in her home. The image is obviously taken with a lower F/ as the outer parts og the image are out of focus.

Contextually, the image has been taken outside for different reason, and that being that it makes the model more comfortable in their own space. By taking the photograph from outside the building, Soth sticks to an important though he keeps in mind; to allow the subject t to be photographed in their own home. By leaving the room that the subject is in, it should allow them to be even more comfortable inside their own personal space, and this allows Soth to capture the most neutral, relaxed and free image of the subject possible. His reasoning for photographing people in their homes is to find chemistry with strangers while photographing loners and dreamers. This directly links to the image of Anna above in relation to the fact that she may be lonely being an older woman. Alec Soth manages to find a simple and calm chemistry with Anna while taking her photograph ,while she lets him take look into her life.

“I fell in love with the process of taking pictures, with wandering around finding things. To me it feels like a kind of performance. The picture is a document of that performance”

Alec Soth

Henry Mullins was the first professional photographer to move to jersey and establish a portraiture business in the early days of photography. Mullins moved to Jersey in July 1848, and set up a studio known as the Royal Saloon, at 7 Royal Square, where he worked for 26 years. A wide collection of his photographs (now held by La Société Jersiaise) shows that there where plenty of willing people on the island prepared to pay half a guinea (promoted as “one half of that in London”) to have their portrait taken by him.

To the right is an early and brilliant quality portrait. A Mr Bolton, photographed by Henry Mullins in 1849-50. Mullins speciality was ‘Cartes de Visite’. The photographic archive of La Société contains a massive collection of these, the on line archive contains 9600 images, and the majority of these are sets of up to 16 photos taken in a single sitting.

A very early Daguerrotype (a unique image on a silvered copper plate) portrait by Henry Mullins of a woman dressed beautifully. The Daguerrotype was the first successful photographic process.

Mullins was also popular with officers (as well as of their wives and children) of the Royal Militia Island of Jersey, as it was very popular to have portraits taken. The pictures of these officers show clearly the fashion in the mid-1800s, being long hair, whiskers and beards.

‘When we love someone we experience the same positive thoughts and experiences as when we like a person. But we also experience a deep sense of care and commitment towards that person. Being “in love” includes all the above but also involves feelings of sexual arousal and attraction.’ – https://theconversation.com/what-is-love-139212

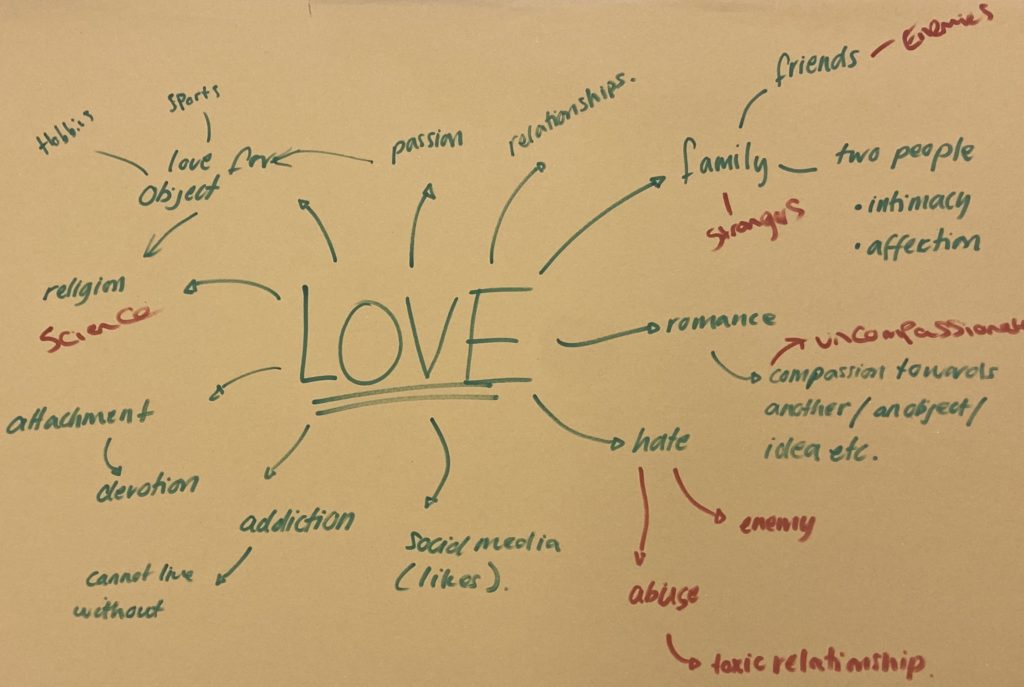

There are many different ideas of what love is. Love can be an addiction, a relationship, friendship, and many more other things. It’s not only people who perceive, show and feel love in the same way, for example, many cultures have different values and feelings toward ‘Love’.

You don’t always have to love one person/ people, many other forms of love can be toward an object or idea, e.g. religion. Many political views come from love such as controversial views about ‘free love’ and things such as polygamy, gay couples and other alike topics. Many movement have been started to fight these issues.

Carolyn Drake tanks about her lover, Andres, who doesn’t particularly like being photographed. Waking up a couple hours before him, she can’t resist to snap a shot to express how natural the moment is. She states ” Love is a complicated thing. I see the pictures as an expression of love, but also of the selfishness in love.”

Tomas Munita is an independent documentary photographer. He focuses on photographing social and environmental issues. In the photos above, he documents refugees with their families crossing the Naf river. His photos explore a strong sense of love and community in difficult times.