Monthly Archives: July 2020

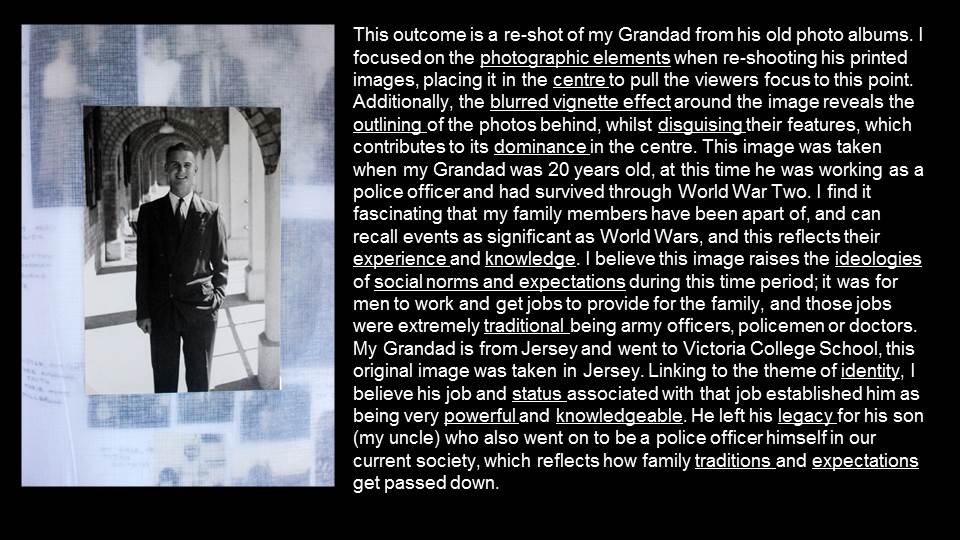

Filters

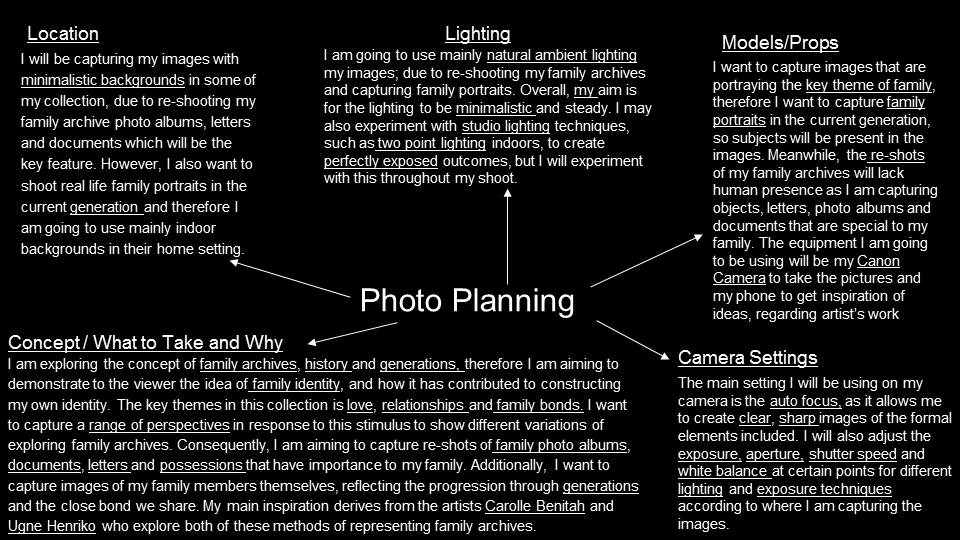

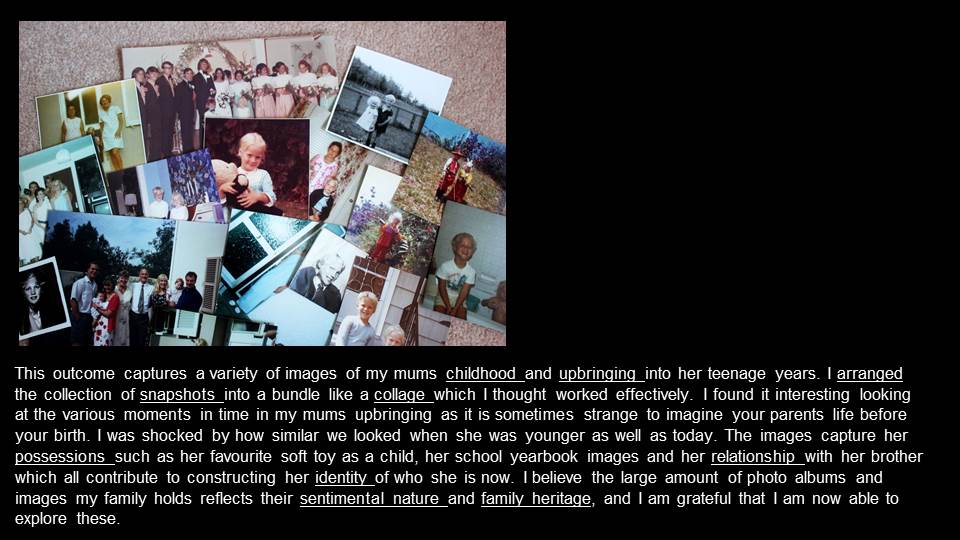

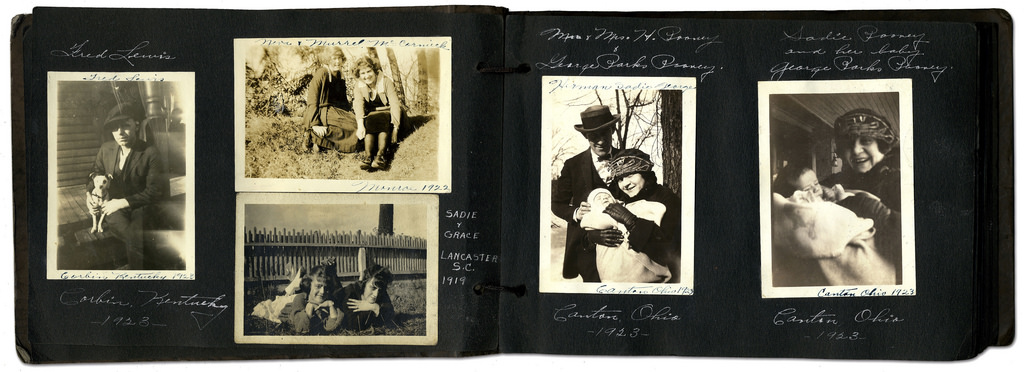

SUMMER TASK: FAMILY ARCHIVES

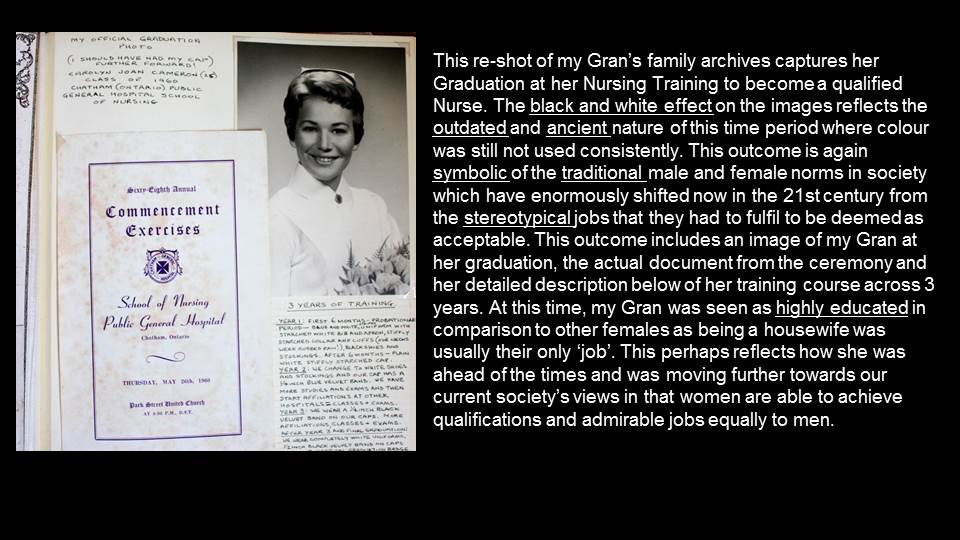

ESSAY: WHAT MAKES AN IMAGE ‘ICONIC’?

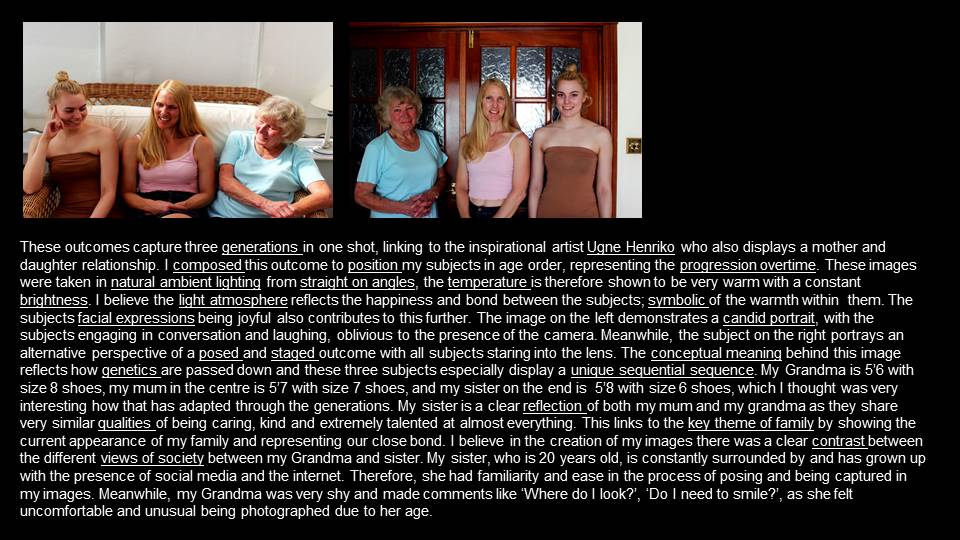

What Makes an Image Iconic?

There are many factors to think about when you are considering an image to be iconic. The actual definition of iconic is, relating to or of the nature of an icon. This infers that images are usually iconic if it contains a person or thing regarded as a representative symbol or as worthy of veneration.

There must be some criteria when considering an image to be iconic since it’s a strong word for an image or anything in general to be labelled as. Susan Bright asked, when thinking about criteria “What is the social value of the image?”, “Does it reinforce or undermine dominant ideologies?”, “Where does it sit in the history of photography and in social history?”, “Does it have any metaphorical messages beyond the frame?” These questions usually identify the iconic nature of an image. For example, if the social value is strong, if it reinforces dominant ideologies, if it sits recently and popularly in photography or social history and if it has strong metaphorical messages beyond the frame, an image usually becomes iconic.

An iconic image is well-known and extremely popular. Even if an individual might not know the context or background of the image, they will have recognized it from media sources, posters, merchandise etc. and would have had many connections with the photograph. You may even say that the image is overused. Take the Queen, for example. Her effigy has been reproduced 220 billion times in more than 130 different colors. It’s been on stamps, money, merchandise etc. Her image is said to be one of the most iconic images in the world, and we would all know it if we saw it.

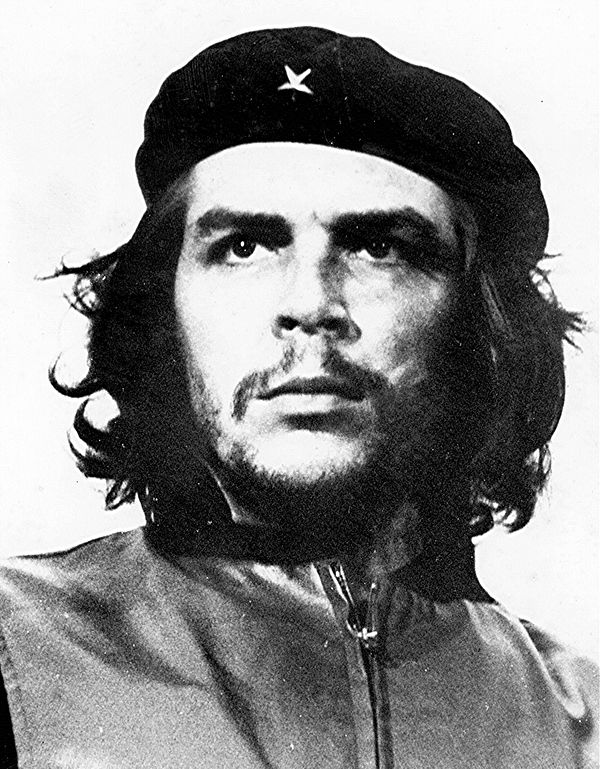

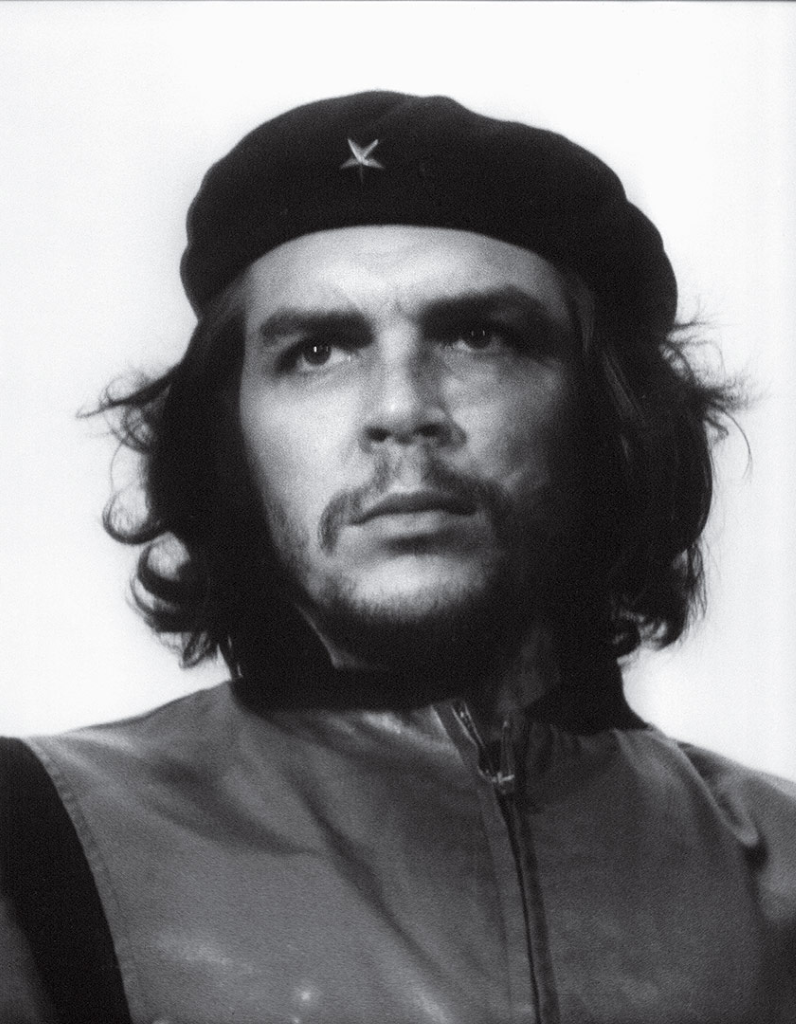

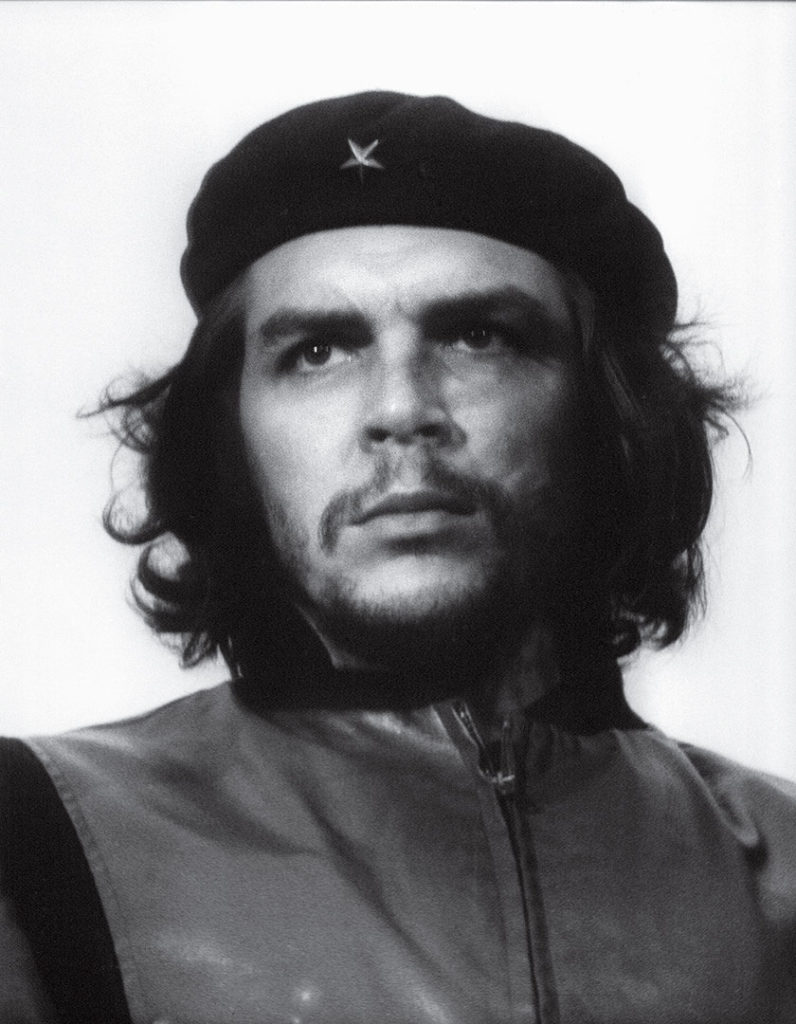

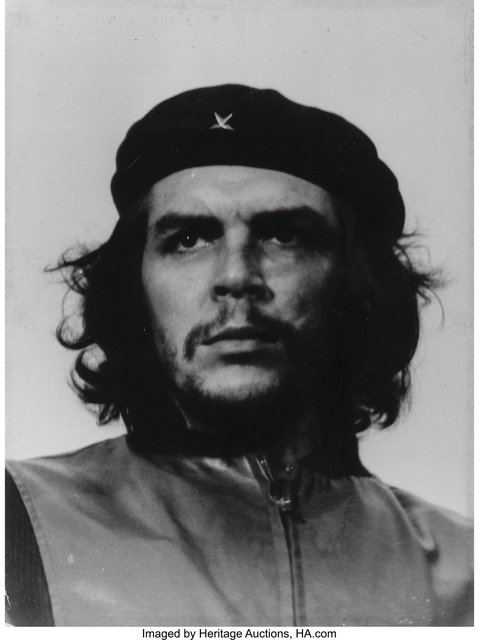

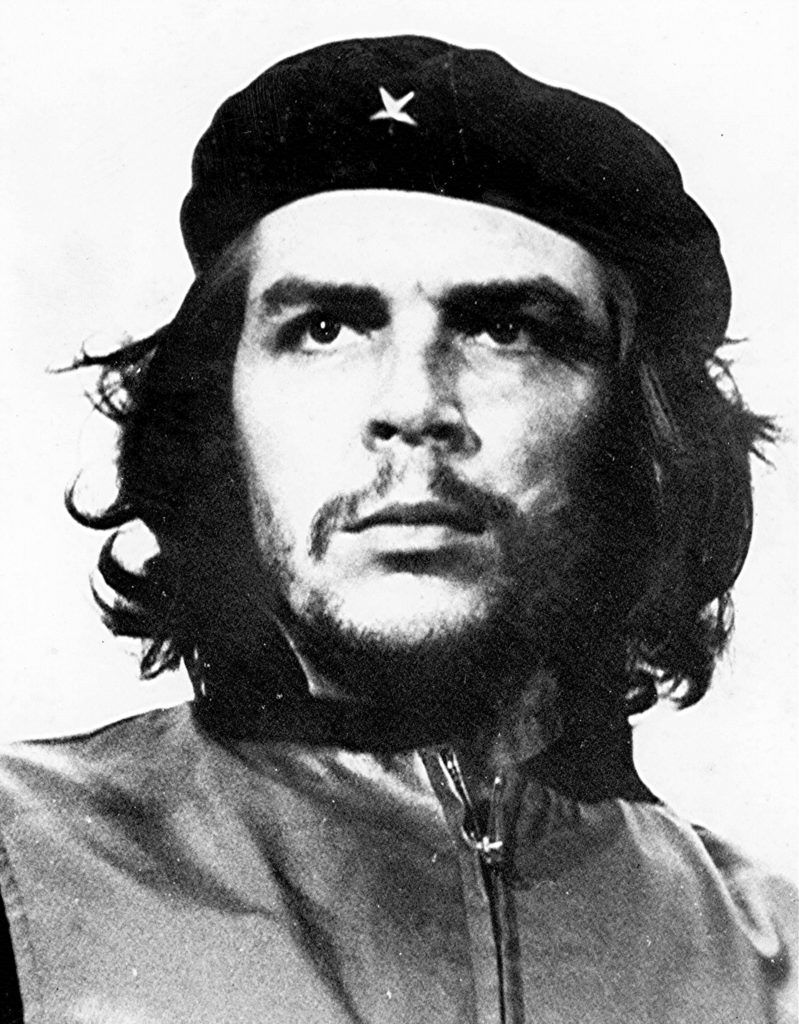

Another factor when considering whether an image is iconic or not is the photographic strategies that are used. For example, this image to the bottom of this paragraph is Guerrillero Heroico. It is an iconic photograph of Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara taken by Alberto Korda. There are many photographic strategies within this image that help upkeep and enhance its iconic view. For example, the camera angle is from below, making the subject appear large, and powerful. The original image was much wider, however it has been cropped for dramatic effect and other photographic information within the image has been removed to make it even more graphic and to single the subject out, to again enhance his power. The black and white were enhanced when the image was printed and reproduced, the photo was therefore made to look more dramatic and important. His gaze is also important, it shows his vision and strength, especially since it is upturned. Korda said himself, as he took the image, he was drawn to Guervara’s facial expression which showed, what he said,” absolute implacability” as well as anger and pain. The Maryland Institute College of Art called this image” a symbol of the 20th Century and is one of the most famous images of all time. Versions of it have been painted, printed, digitized, embroidered, tattooed, silk screened, sculpted or sketched on nearly every surface imaginable.

Consider this image below, let’s discuss the criteria. This photograph was taken at a Black Lives Matter protest and has been widely spread throughout the media as it shows a black person helping a white person. This provides a wonderful message of equality and love, and how races can join to fight against something that is wrong within the world.

What is the social value of the image? This image is highly socially valuable. The protest in general, are very valuable to not only to black lives, but to all races that support the movement, have experienced racism or police brutality, family members of people who have experienced this etc. This is not only valuable to a certain community of people. Police brutality is also a huge problem that nearly every single member of the public disagrees with, therefore the protests are highly valuable, thus images of the protests are highly valuable. This image in particular would be valuable because it shows two kinds of races together in unity and not hate. Thus going against racism which is a problem the public want to solve.

Does it reinforce or undermine any dominant ideologies? The answer is simply yes. The dominant ideology that has been maintained for a number of years is that white people are superior to black people, and also that police are superior to the citizens and are able to do whatever they like. The protests were mainly to stop police brutality after the nursed of George Floyd, however this image undermines the ideology that white people are superior to black people. This specific image shows that we are all equal and that we should help each other, regardless of our race. Within this image it also shows the white person as inferior and a black person as superior as he is helping the white person. However, I disagree with this message as equality is what we should be looking for, just an interesting perspective.

Where does it sit in the history of photography and in social history? It sits very recently in both. Which is most probably why the image has done so well. The image is relevant to today’s issues and today’s events. The camera quality shows that it sits recently in photographic history, and more obviously the date it was taken, and also the clothing within the image and the technology shown within the image.

Does it have any metaphorical messages beyond the frame? I touched on a number of messages above that this image may have. It has a metaphorical message of equality and how no matter our race, we should all help each-other. We should not prejudice due to our skin colour. We are all human, we all bleed the same, therefore we should take care of each other.

The photographic strategies used are also interesting. It is taken almost face-on however a little below to make the black man appear strong and large, which is the opposite of racists ‘beliefs’ of black people which are that they are inferior and weak. The photographer also got it from an angle where the two subject’s are surrounded by police in lots of protective gear, enforcing the idea of police brutality and fear of the police, however the two seem almost untouched by the police, giving the message of freedom and rebellion against the brutal police force.

Because that specific image reached all of that criteria positively, we may say that it is an iconic image.

What makes an image iconic?

The question “what makes an image iconic?” has been asked over and over again throughout the history of photography, and with good reason. Photography has developed into an art form and an aide to journalism as well as a method of historical documentation, all of which have contributed to a massive amount of images being produced and spread all through the media and online constantly. In fact, according to a 2014 survey, an average number of 1.8 billion images are digitally uploaded every single day, and the vast majority of them are almost instantly lost in the depths of personal social media accounts, or news articles that are quickly discarded and lost to time. So if so many images are being produced with little to no consequences, how is it that certain images become so famous and well-known, so much so that some iconic images are familiar to us without us ever knowing the true context of them?

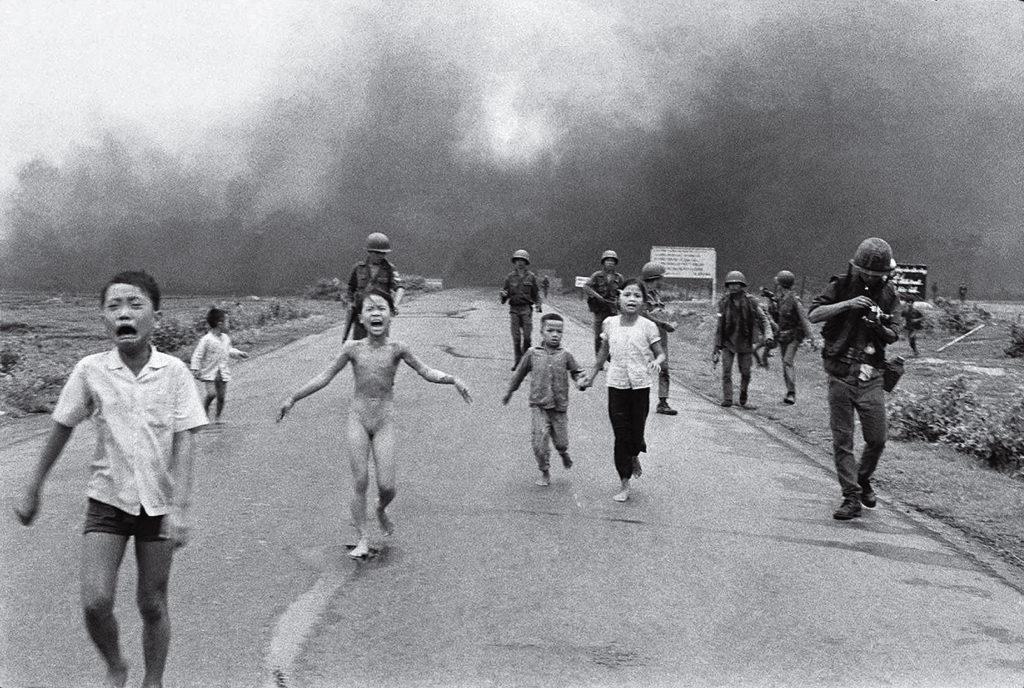

Currently, social media plays a vastly important role in the world of news and journalism, with viral social media stories being picked up by actual newspapers, stories being shared online through sites like Twitter or Facebook, and many young people relying on social media to find out global news stories as they come into contact with them. As a result, the “aestheticism” of an image plays a big role in whether it becomes iconic or not in today’s world, because it needs to be eye-catching and emotionally-charged enough so that people share it with others and remember it as well as its original context. Some people may argue that this is unfortunate and unfair, that it is a clear indicator of how images and legitimate news nowadays have been completely devalued as a result of the younger generations being vain, narcissistic and obsessed with outward appearances. However, I strongly disagree with this. Throughout the history of iconic images, there is a clear pattern of the more poetically powerful and artistic images becoming incredibly popular and well-known time and time again, and often they (even unintentionally) mirror famous paintings and methods found in art such as the Golden Triangle or the Fibonacci Spiral. Consequently, it seems that in order for humanity to view a certain image as iconic and for that image to stand the test of time, it must have some sort of artistic structure. This can clearly be seen in iconic photos throughout history, for example Joe Rosenthal’s 1945 image of US soldiers raising an American flag, or the famous kiss between a US sailor and a woman in Times Square at the end of the Second World War (“V-J Day in Times Square), or the “Saigon Execution” image from the Vietnam War.

Additionally, an image can become iconic due to its context, either at the time or as a result of events afterwards, and whether it “reinforces or undermines dominant ideologies”, as in Susan Bright’s article (“Why is it famous?”). Some historical events carry such significance that they can elicit an emotional reaction from people simply by looking at them, for example how many of the images taken on 9/11 have become iconic and are widely known even to people who were not alive during those events. An example of this form of iconic imagery can be seen below.

This image was taken by a South African photographer called Kevin Carter in 1993, during the famine in Sudan, and it features a young boy (initially believed to be a girl) struggling to reach a United Nations food centre roughly half a mile away. The boy is clearly emaciated and is suffering from extreme famine and malnutrition, but it is the vulture in the background, hovering over the close-to-dying boy, that makes this image so powerful in my opinion. This almost artistic macabre imagery of the shadow of Death makes this image almost painful to look at, and creates a sense of guilt for the viewer, as they would most likely be looking at this in a newspaper, magazine or online article, from a position of privilege and comparative luxury in contrast with the small child dying alone in the wilderness. In fact, even directly after this photograph was taken, the photographer himself was so struck with guilt and empathy for the child that he helped him get to the feeding centre, and the child survived the ordeal. However this image was heavily criticized by people who asked why Carter even stopped long enough to take the photo at all, and even though he was awarded with the Pulitzer Prize for this image, he was so consumed by guilt and depression, traumatised by the things he had witnessed, he committed suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning only months after receiving the prize, in 1994.

The image features two main figures, positioned almost opposite to each other so that the image can be divided into two clear sections, representing Life and Death. The background of the image is mainly sepia-toned and features a brown colour palette, which increases the contrast between the background and the two figures in the foreground, as they are both darker colours and are more tonally contrasted. It clearly depicts the social issues of famine, poverty, but also subtly presenting the effects of extreme wealth inequality and the after-effects of colonialism in African countries.

This image is much more recent, having been taken during the BLM protests in London in mid-June this year, and it presents a black man carrying a white man to safety amidst police officers and other protesters. It reverses the typical “White Saviour” imagery that can be seen to perpetuate many forms of activism, the travel industry, and even the film industry. The issue of the “White Saviour” is that it shows white people “saving” struggling people of colour instead of showing those people of colour surmounting their own barriers, as is often the case, and it raises white voices talking about racism instead of simply amplifying the voices of people of colour who have been talking about racism and fighting racism for generations with relatively little media attention. It can also be found in aid-trips to African countries, which although probably had good intentions, end up perpetuating the stereotype of African countries as all being poor, war-ridden and rife with famine and disease. This photograph goes against all that, and as a result may be more memorable to many viewers who have been subjected to the same image of the nice, kind white person saving the poor, hungry black person again and again and again.

This photograph, much like the previous one, is centered around two figures, however in this case they are both human instead of a human and an animal. Both images depict social issues, however this image is different in that it illustrates racism and current affairs, which may help it become a more iconic image, as images with political meanings behind them that were taken during periods of great societal change often tend to be more long-lasting and become “iconic” in the public’s view. The image is in full colour, but the contrast between the two main figures’ skin tones is powerful enough to draw the eye immediately and becomes the main focal point of the image. The camera lens was also slightly tilted when the pictures was taken, meaning the image and the people it features are angled, which adds a sense of movement to the photograph in its entirety and makes it more dynamic and actually interesting.

In conclusion, it tends to be the context in which they were taken that makes certain images iconic (or to go viral, in the online world), whether that be their political and global context, for example photographs taken during crucial moments in history or depicting traumatic moments in time, or their emotional context, for example if it depicts a particularly powerful emotion such as pain, fear, love or hatred. Symbolism also plays an important role, for instance the imagery of Life vs Death, or the White Saviour, or even the ever-popular Madonna and Child, a theme often found in religious imagery but also (unconsciously or not) replicated throughout many iconic images and art.

Iconic image Essay: In Progress

Alberto Korda- Guerrillero Heroico (1960)

What Makes an Image Iconic?

This snapshot portrait of Che Guevara is arguably one of the most iconic images taken in recent modern times. The majority of the world’s population will recognize it to a certain extent. However, why and what makes it so iconic? Perhaps an image of Martin Luther King giving his famous “I have a dream speech” should be more iconic due to its maintained relevance to society and its obvious meaning which comes alongside it. Or on the contrary, is this what gave the image of Guevara it’s status? The illusive and easily appropriated nature of the photo is why it is so far spread. A quote from a passage in “Why is it famous” written by Susan Bright states: “What is the social value of the image…does it reinforce or undermine dominant ideologies”. In my opinion the image neither undermines or dominates current ideologies and yet does both, this is what gives the graphic image the power it has. Its flexibility gives it the power of being socially valuable. Its heavy weight can be shifted in many directions, especially over the length of time this photo has been relevant.

What makes an image iconic?

Alberto Korda,Guerrillero Heroico 1960

Just before Alberto Korda took this iconic photograph of Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara, in Havana Harbor a ship had exploded , killing dozens of dockworkers and the entire crew. Covering the funeral for the newspaper Revolución, Korda focused on Fidel Castro, who in an raging speech, accused the U.S. of causing the explosion. The two frames he shot of Castro’s young ally were a seeming afterthought, and they went unpublished by the newspaper.

After Guevara was killed leading a guerrilla movement in Bolivia nearly seven years later, the Cuban regime embraced him as a martyr for the movement, and Korda’s image of the beret-clad revolutionary soon became its ever lasting symbol.

Overall, Guerrillero Heroico was seized by artists, causes and admen around the world, appearing on everything from protest art to underwear to soft drinks. It has become the cultural shorthand for rebellion and one of the most recognizable and reproduced images of all time, with its influence long since transcending its steely-eyed subject.

From a photographic prospective of what makes an image iconic; a lot of professional photographers would say that an angle of a portrait can make the difference of a “basic photo” of another person and making a person look heroic and powerful, only by taking the photo from lower angle like the photographer above has done.

The Falling Man

The most widely seen images from 9/11 are of planes and towers, not people. Falling Man is one of those few. The photo was taken by Richard Drew and in the moments after the 11th September 2001 attacks. This one man’s escape from the collapsing buildings was a symbol of individuality against the backdrop of faceless skyscrapers. On a day of this tragedy, Falling Man is one of the only widely seen pictures that shows someone dying without the gore. The photo was published in newspapers around the U.S. in the days after the attacks, but backlash from readers forced it into being less publicized as many people felt traumatized just by looking at the photo as well as saying it was extremely morbid. It can be a difficult image to process, as many have said, but the man perfectly bisecting the iconic towers as he drops toward the earth has an artistic feel to it as dreadful as that sounds. The Falling Man’s identity is still unknown, but he is believed to have been an employee at the Windows on the World restaurant, which was on the top of the north tower. The true power of Falling Man is less about who its subject was and more about what he became.

What makes an iconic image?

The term iconic often describes something or someone that is considered symbolic of something else, which can then connote different feelings or connections of spirituality, evil, corruption etc. Therefore an iconic image depicts a specific scene often with impactful historic or eventful context, as well as a collection of many different outside aspects. Iconic images also hold a social value and you can evaluate its importance with how it may reinforce or undermine dominant ideologies.

An example of a highly used iconic image is a portrait of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, taken by Cuban photographer Alberto Korda in 1960. The portrait is named ‘Guerrillero Heroica’, and has become highly recognisable even without its political context which portrayed Che as ‘a symbol of militant Marxism’. To be continued…

Summer project

During the summer it is important that you keep training your eye and practice making images. Below are two tasks, ICONIC IMAGE and FAMILY ARCHIVE that you can work on during the break which will prepare you for the next academic year in September.

Publish all your work on the blog before returning to school on Thurs 3 September where we will be discussing your response to making an iconic image as well as research into your family archives and history. Best of luck!

ICONIC IMAGE: The first task is a photographic response to the essay: What makes and iconic images. Try and make an image either in camera as observed reality or a staged approach, or using a combination of digital manipulation in post production that in your view creates and iconic image. Write a short evaluation that explains your intentions and thought processes.

Alberto Korda

Nick ut

Kevin Carter

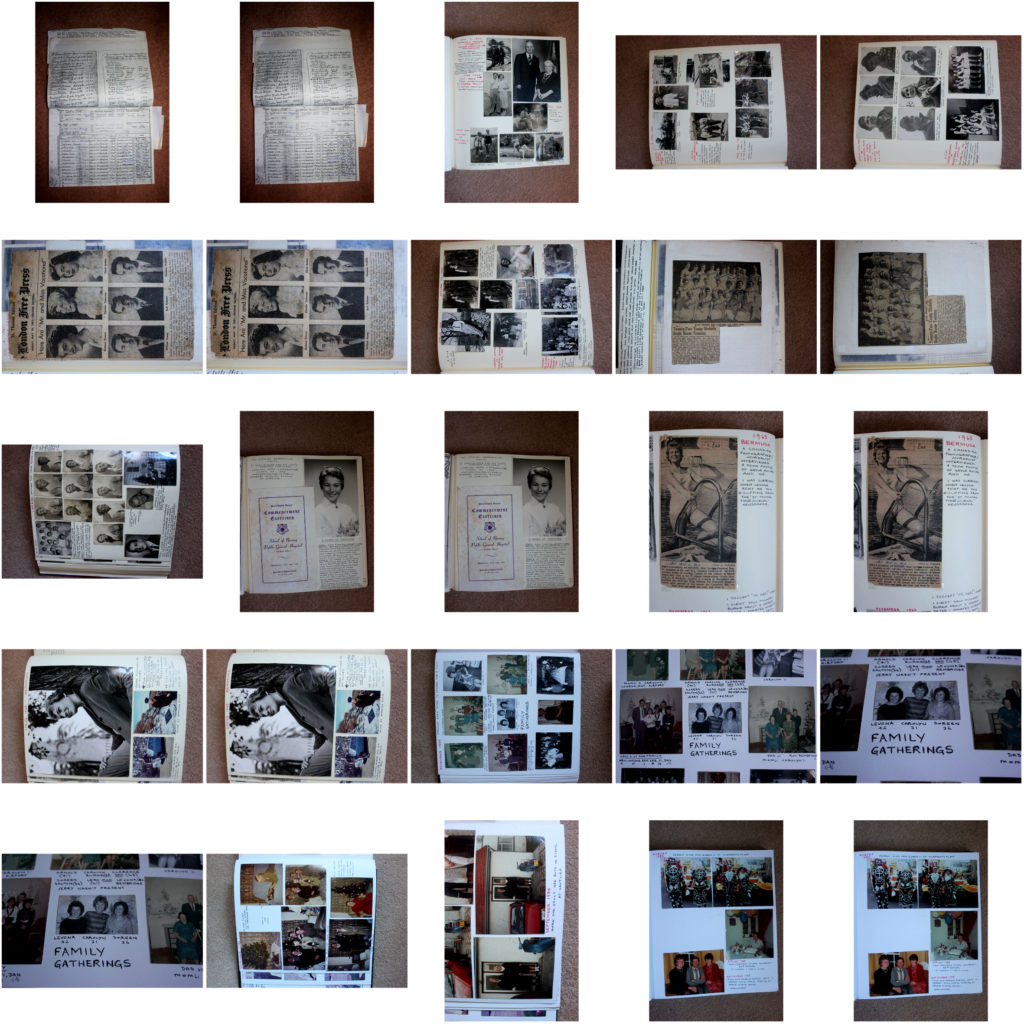

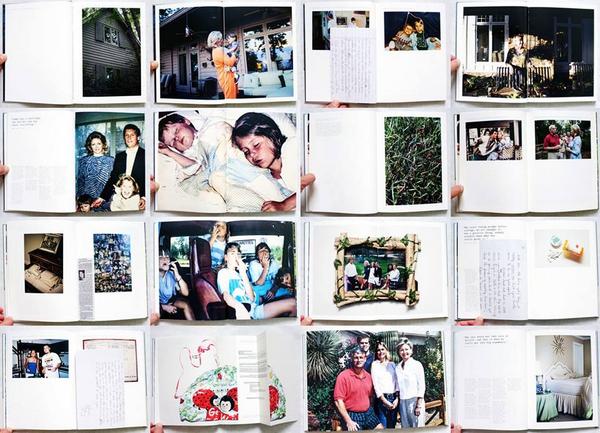

FAMILY ARCHIVES: Explore your own private archives such as photo-albums, home movies, diaries, letters, birth-certificates, boxes, objects, mobile devices, online/ social media platforms and make a blog post with a selection of material that can be used for further development and experimentation using a variety of re-staging or montage techniques .

Archives can be a rich source for finding starting points on your creative journey. This will strengthen your research and lead towards discoveries about the past that will inform the way you interpret the present and anticipate the future. See more Public/ Private Archives

For example, you can focus on the life on one parent, grand-parent, family relative, or your own childhood and upbringing. Ask other family members (parents, grand-parents, aunties, uncles) if you can look through their photo-albums too etc.

TASKS STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE:

- Either scan or re-photograph archival material so that it is digitised and ready for use on the blog and further experimentation.

- Plan at least one photo-shoot and make a set of images that respond to your archival research. This can be re-staging old photos or make a similar set of images, eg. portraits of family members and how they have changed over the years, or snapshots of social and family gatherings.

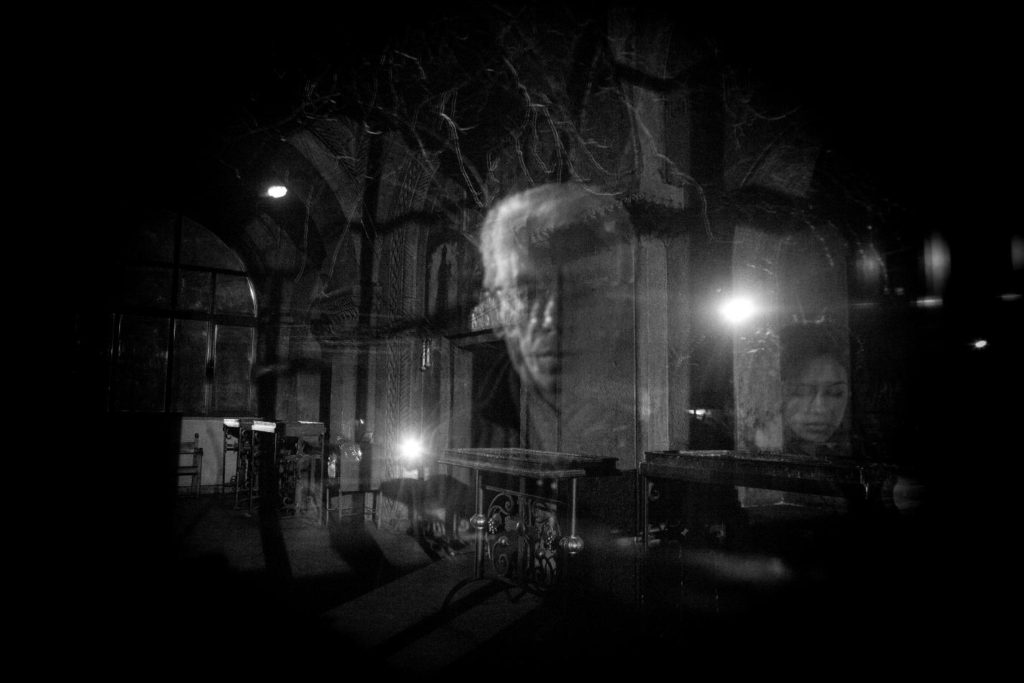

- Choose one of your images which relates to the theme of family (e.g. archive, family album, or new image you have made) and destroy the same image in 5 different ways using both analogue and digital method techniques. Eg. Reprint old and new photos and combine using scissors/ tearing and glue/ tape. In Photoshop use a variety of creative tools to cut and paste fragments of images to create composites.

Extension: Choose a second image and destroy it in 5 new or other ways.

cof

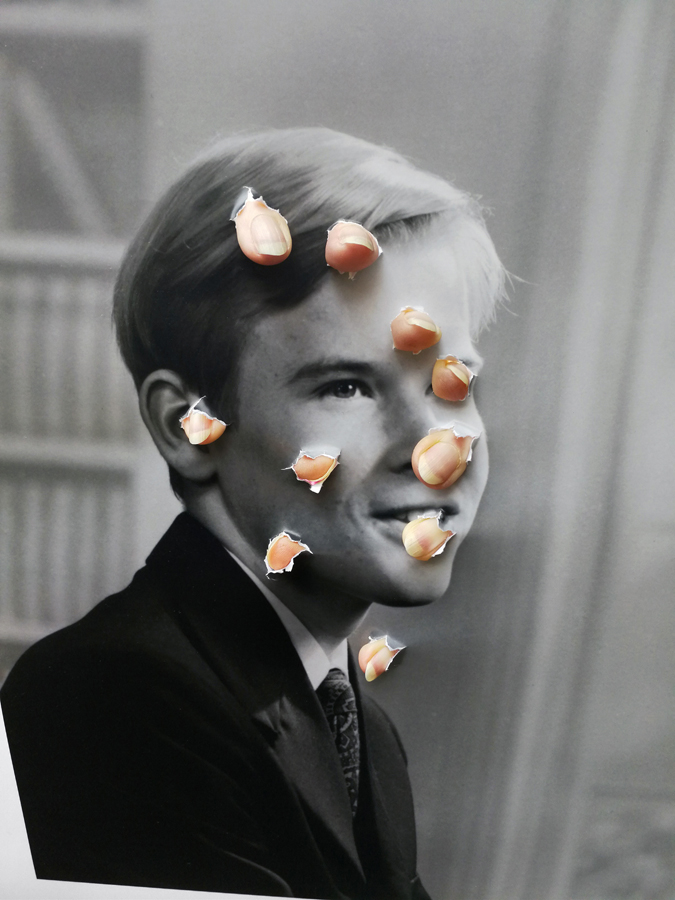

Under Oath, 2017

Jonny Briggs: In search of lost parts of my childhood I try to think outside the reality I was socialised into and create new ones with my parents and self. Through these I use photography to explore my relationship with deception, the constructed reality of the family, and question the boundaries between my parents and I, between child/adult, self/other, nature/culture, real/fake in attempt to revive my unconditioned self, beyond the family bubble. Although easily assumed to be photoshopped or faked, upon closer inspection the images are often realised to be more real than first expected. Involving staged installations, the cartoonesque and the performative, I look back to my younger self and attempt to re-capture childhood nature through my assuming adult eyes.

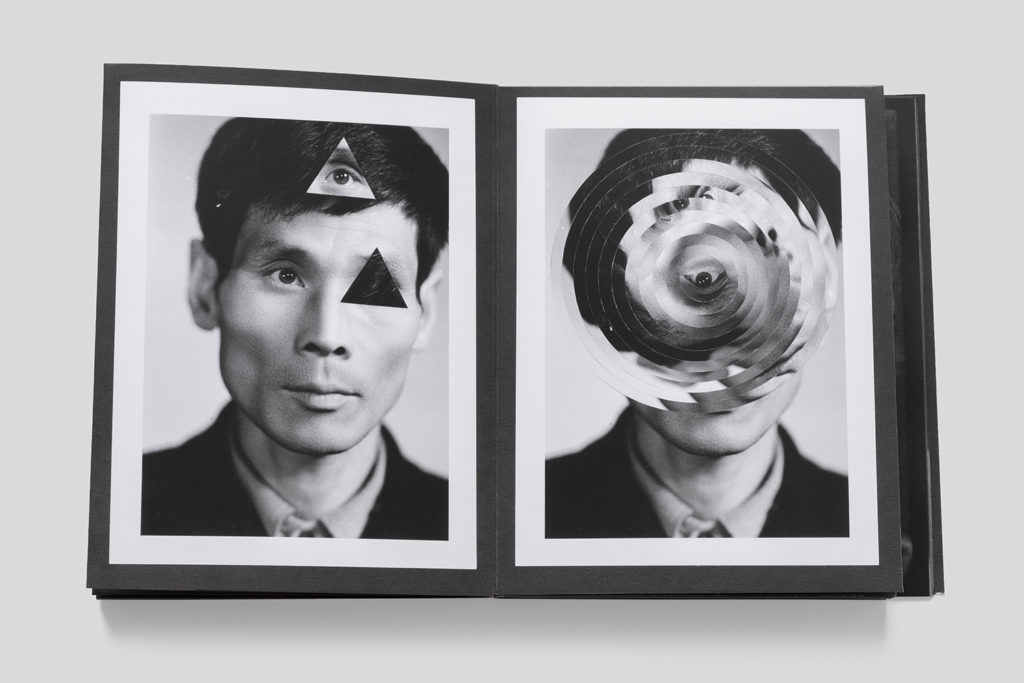

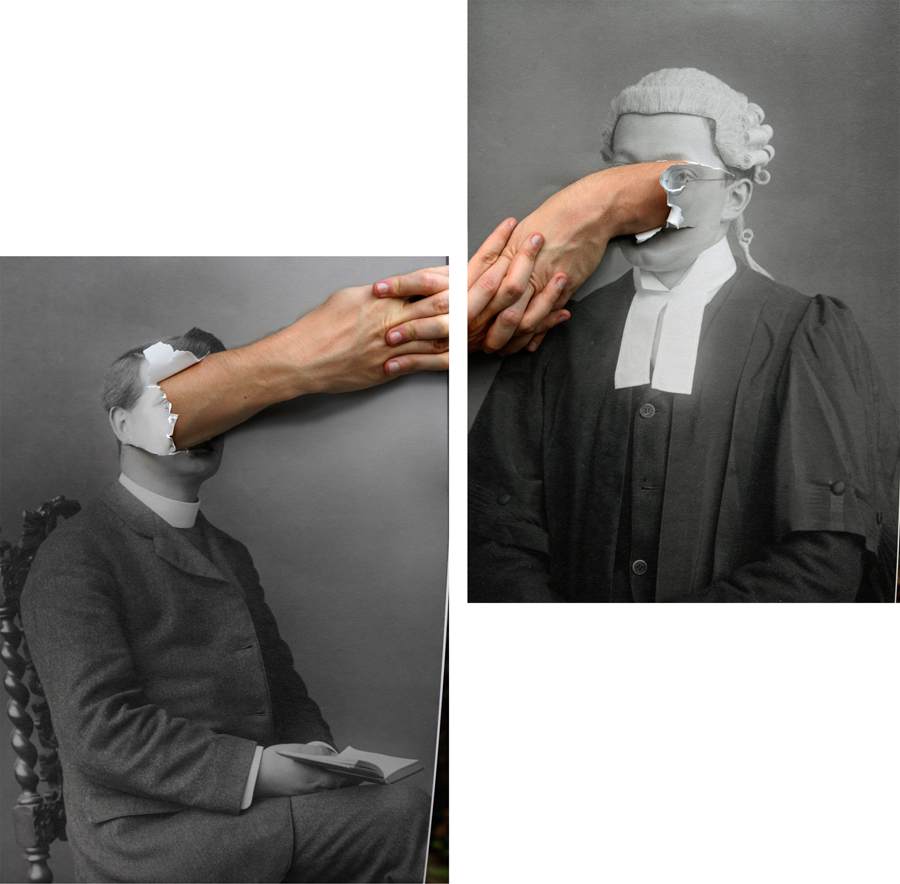

Thomas Sauvin and Kensuke Koike: ‘No More, No Less’

In 2015, French artist Thomas Sauvin acquired an album produced in the early 1980s by an unknown Shanghai University photography student. This volume was given a second life through the expert hands of Kensuke Koike, a Japanese artist based in Venice whose practice combines collage and found photography. The series, “No More, No Less”, born from the encounter between Koike and Sauvin, includes new silver prints made from the album’s original negatives. These prints were then submitted to Koike’s sharp imagination, who, with a simple blade and adhesive tape, deconstructs and reinvents the images. However, these purely manual interventions all respect one single formal rule: nothing is removed, nothing is added, “No More, No Less”. In such a context that blends freedom and constraint, Koike and Sauvin meticulously explore the possibilities of an image only made up of itself.

Veronica Gesicka Traces presents a selection of photomontages created by Weronika Gęsicka on the basis of American stock photographs from the 1950s and 1960s. Family scenes, holiday memories, everyday life – all of that suspended somewhere between truth and fiction. The images, modified by Gęsicka in various ways, are wrapped in a new context: our memories of the people and situations are transformed and blur gradually. Humorous as they may seem, Gęsicka’s works are a comment on such fundamental matters as identity, self-consciousness, relationships, imperfection.

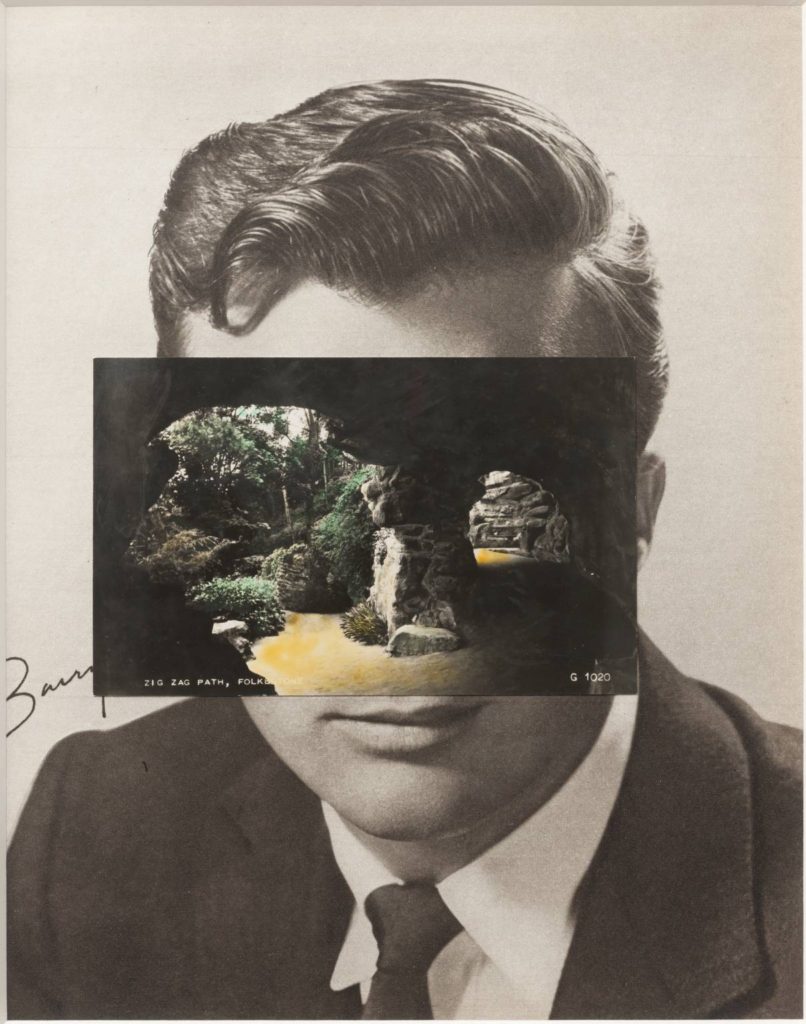

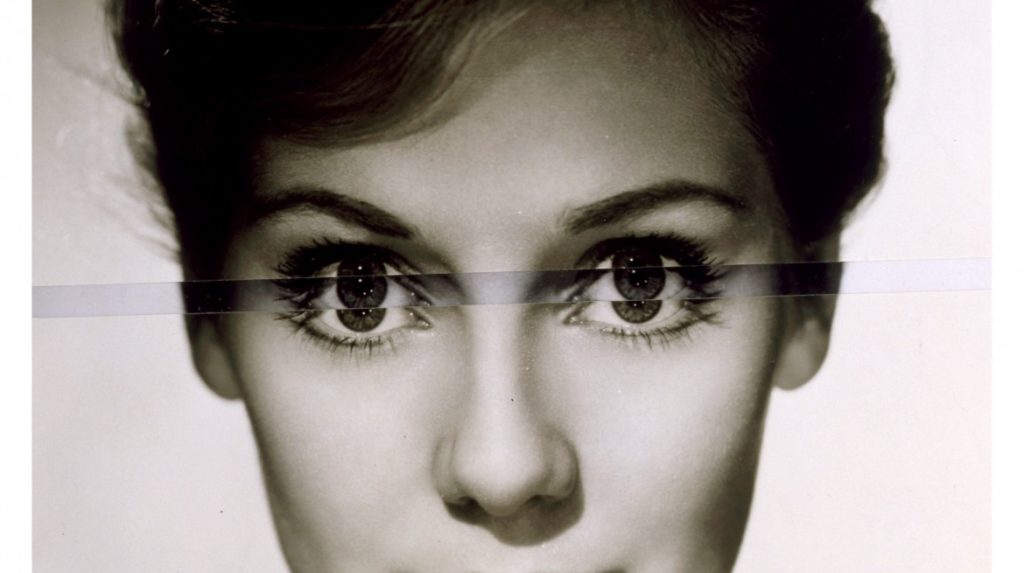

John Stezaker: Is a British artist who is fascinated by the lure of images. Taking classic movie stills, vintage postcards and book illustrations, Stezaker makes collages to give old images a new meaning. By adjusting, inverting and slicing separate pictures together to create unique new works of art, Stezaker explores the subversive force of found images. Stezaker’s famous Mask series fuses the profiles of glamorous sitters with caves, hamlets, or waterfalls, making for images of eerie beauty.

His ‘Dark Star’ series turns publicity portraits into cut-out silhouettes, creating an ambiguous presence in the place of the absent celebrity. Stezaker’s way of giving old images a new context reaches its height in the found images of his Third Person Archive: the artist has removed delicate, haunting figures from the margins of obsolete travel illustrations. Presented as images on their own, they now take the centre stage of our attention

There are different ways artists and photographers have explored their own, or other families in their work as visual storytellers. Some explore family using a documentary approach to storytelling, others construct or stage images that may reflect on their childhood, memories, or significant events drawing inspiration from family archives/ photo albums and often incorporating vernacular images into the narrative and presenting the work as a photobook.

Rita Puig-Serra Costa (Where Mimosa Bloom) vs Laia Abril (The Epilogue)> artists exploring personal issues > vernacular vs archival > inside vs outside

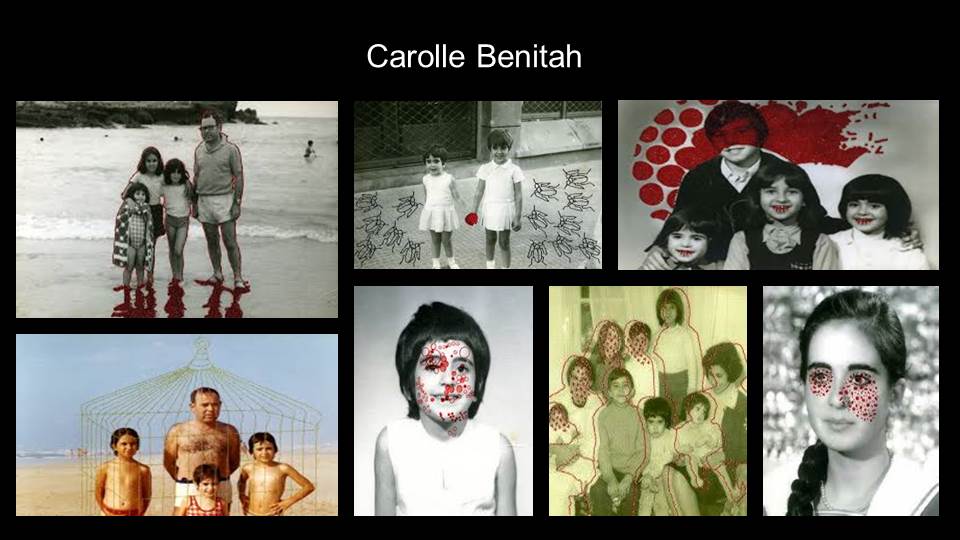

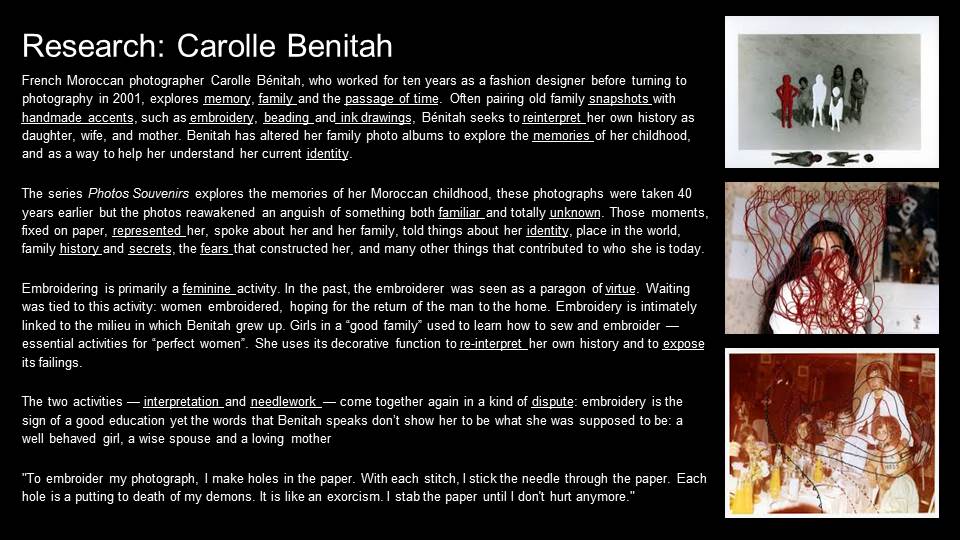

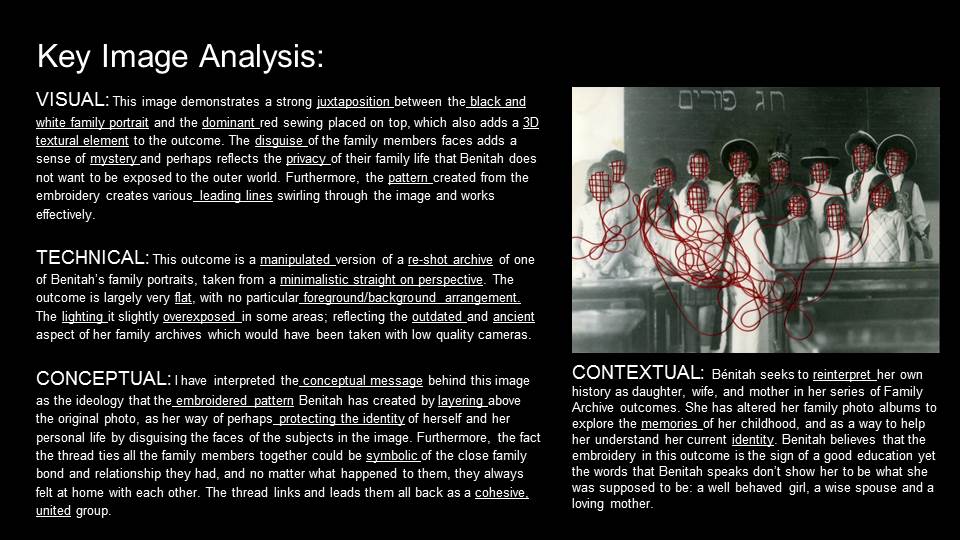

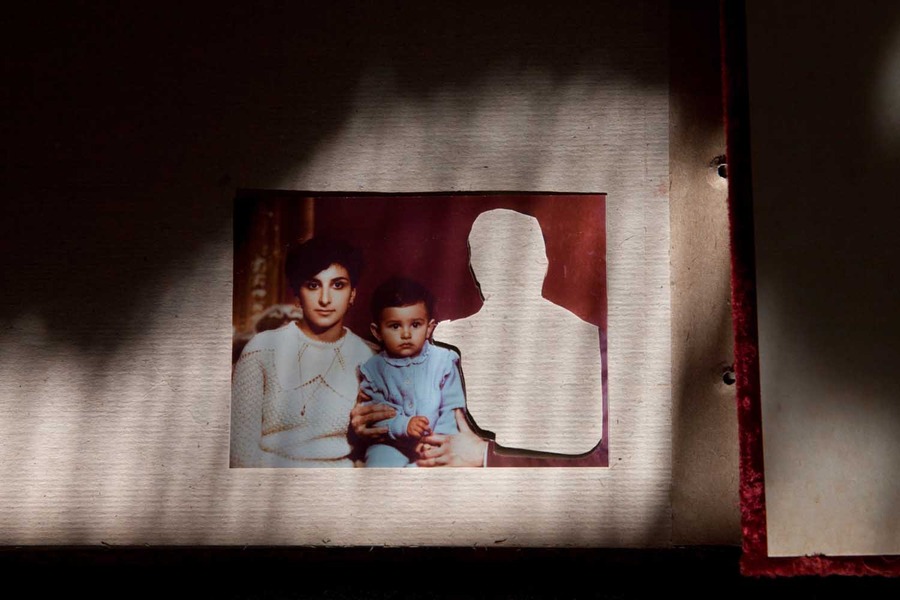

Carole Benitah (Photo Souvenirs) vs Diane Markosian (Inventing My Father) > family > identity > memory > absence > trauma

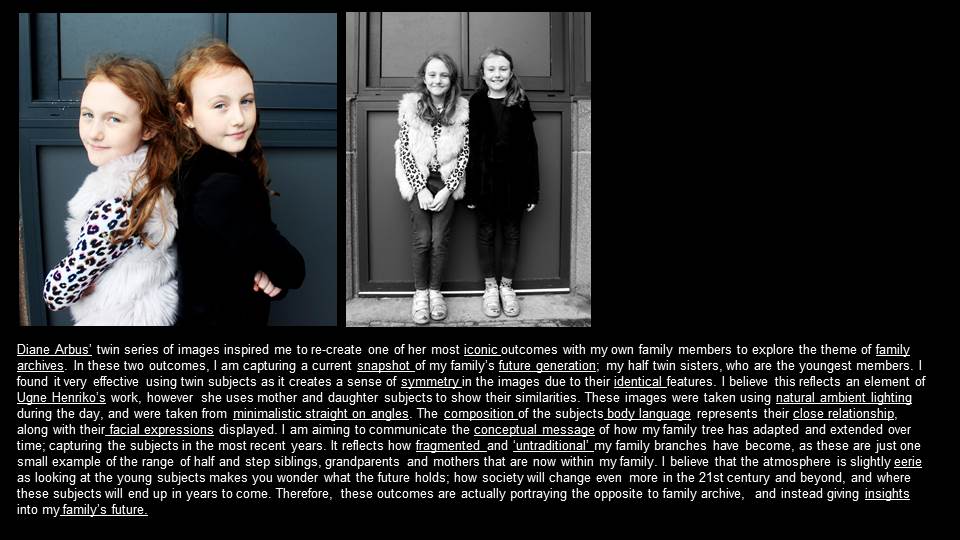

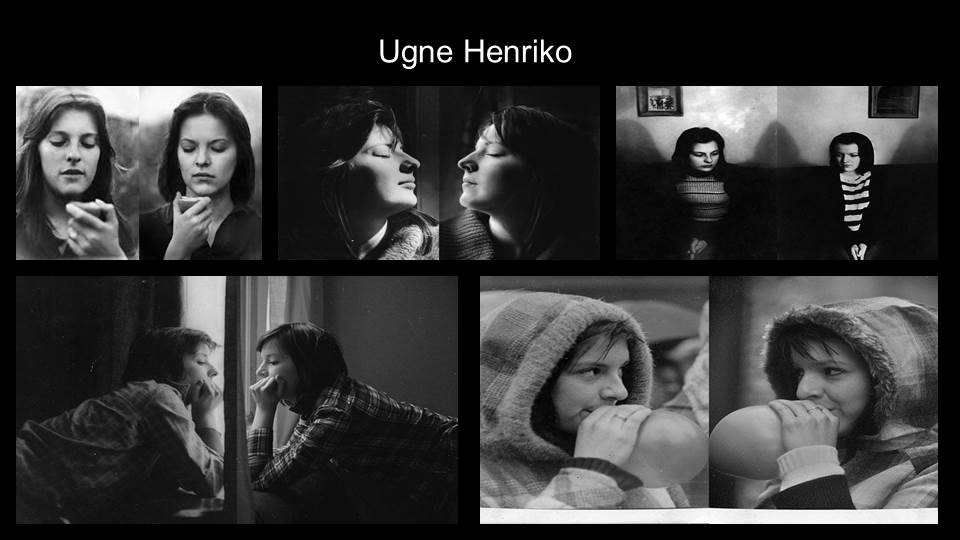

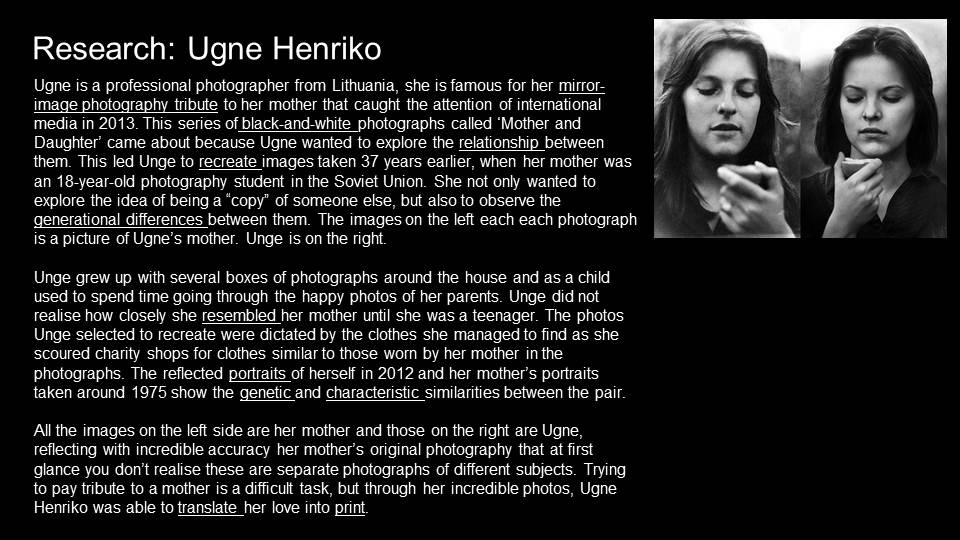

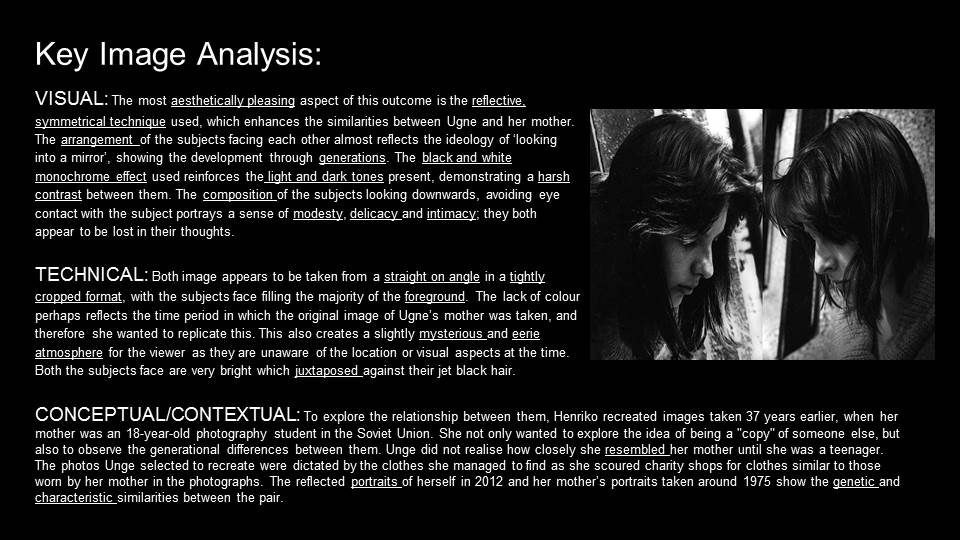

Ugne Henriko (Mother and Daughter) vs Irina Werning or Chino Otsuka > re-staging images > re-enacting memories

Read article in The Guardian

WHAT MAKES AN IMAGE ICONIC?

When a photograph is considered iconic, it relates to the fact that it’s very influential and recognisable, famous even. The images that are labelled ‘iconic’ are embedded in our history and culture, often having a huge global impact on society. They may define a major event in history, or even come to create one. However what about the images, make them iconic?

Alberto Korda’s photograph of Che Guevara taken March 5, 1960 would be one of the most influential photographs in the course of history, becoming the global symbol of revolution and rebellion, but what aspects of the photograph make it so unforgettable?

Susan Bright talks about the photograph of Che Guevara in response to the question ‘Why is it famous’. She talks about the criteria that makes an image iconic, and, for Alberto Korda’s photograph of Che Guevara there seems to be a strong social value that influence its power as an image. There are many technical qualities of the photograph that contribute to it’s memorability, for example, its high contrast in blacks and whites, the upward angle of the camera shot, the focal point only being the face of Che Guevara, looking on with power and strength.

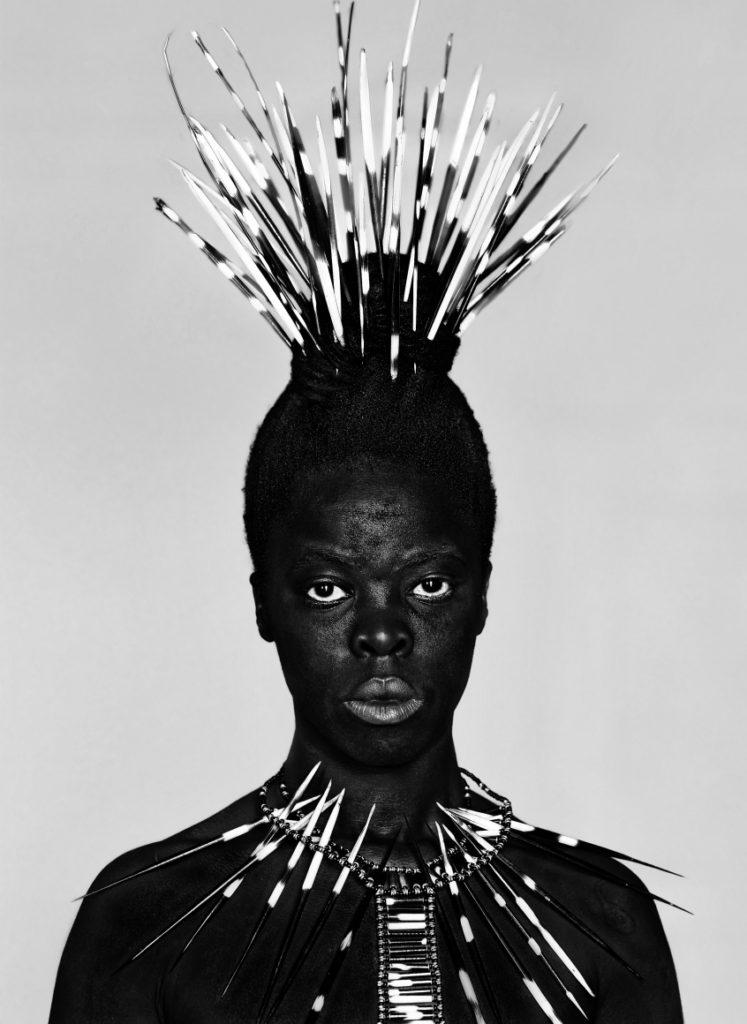

ZANELE MUHOLI

REPRESENTING BLACK LIVES IN THE LGBTQ COMMUNITY

Zanele Muholi is one of the most influential photographers/ artists today, exploring topics such as racism, labour, Eurocentrism and sexual politics, as well as showcasing South Africa’s black lesbian, gay, trans, queer and intersex communities. Muholi is a South Africa queer, non-binary visual activist (who uses the pronouns they/them/their) documenting various peoples lives in townships in South Africa. Their work is often bold and confrontational, addressing issues in racism and politics that come with race.

They focus on an ongoing project called “faces and phases” which depicts black lesbian and transgender people in response to the continuing discrimination and violence the LGBTI community faces. “Muholi’s self-proclaimed mission is ‘to re-write a black queer and trans visual history of South Africa for the world to know of our resistance and existence at the height of hate crimes in SA and beyond.'” –

https://www.yanceyrichardson.com/artists/zanele-muholi?view=slider#8

In another series, Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail the Dark Lioness) Muholi points the camera at themselves to be the model and the photographer, to experiment with characters and looks. They exaggerate skin tones to be darker through editing which increases the depth and contrast of the photograph its self, so they can take back their blackness, and offset the culturally dominant images of black women in modern day media.

- Zabo I, Kyoto, Japan, 2017. From the series Somnyama Ngonyama

MaID X, Durban, 2016

CRITICAL/ CONTEXTUAL

VISUAL

TECHNICAL