‘Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about the things that matter’

— Martin Luther King Jr

“I Have a Dream” is a public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, in which he called for civil and economic rights and an end to racism in the United States.

In the new academic year beginning in September we will be exploring the themes of LOVE & REBELLION in an exciting programme of study that will be centred around visual storytelling and include a variety of outcomes such as designing photo-zines, photobook, write an essay and produce a film. The main shift in your photographic studies from Yr 12 to Yr 13 is to begin to consider images in series that are part of a much larger visual investigation and photographic narrative, rather than just make one good picture!

Initially we had something else planned for the next few weeks until summer break linked to our recent experience of COVID-19 and the subsequent island lockdown. However in recent weeks it was an event in Minneapolis that has caused the largest reaction worldwide. The death of George Floyd has the potential to be a catalyst for change and as image-makers it is our moral obligation to respond to this new reality.

Let’s pause for 8 minutes and 46 seconds and reflect.

Global Context: Racism

Black Lives Matter

Describe racism. How does it manifest itself? What is institutional racism?

Racism takes many forms and can happen in many places. It includes prejudice, discrimination or hatred directed at someone because of their colour, ethnicity or national origin. People often associate racism with acts of abuse or harassment. However, it doesn’t need to involve violent or intimidating behaviour. Take racial name-calling and jokes. Or consider situations when people may be excluded from groups or activities because of where they come from.

Racism can be revealed through people’s actions as well as their attitudes. It can also be reflected in systems and institutions. But sometimes it may not be revealed at all. Not all racism is obvious. For example, someone may look through a list of job applicants and decide not to interview people with certain surnames. Racism is more than just words, beliefs and actions. It includes all the barriers that prevent people from enjoying dignity and equality because of their race.

Racism in Britain: Read personal experience of racism in ‘Something is in the Air’ by Ben Okri, a Nigerian poet and novelist published in the Financial Times last weekend and in ‘Race and Racial Identity are Social Constructs’ by Angela Onwuachi-Willig, a professor of law published in New York Times.

Read article in The Guardian on police brutality in Britain and a view from the lawyer that represented Stephen Lawrence, a black youth who was killed in a racially motivated attack by a group of whites while waiting for a bus with a friend in Eltham, South London on 22 April 1993. Read Labour MP David Lammy’s response to Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s latest decision to set up a Racial Equality Review in response to recent public unrest.

Watch George the Poet discussing Black Lives Matter movement in the UK on Newsnight.

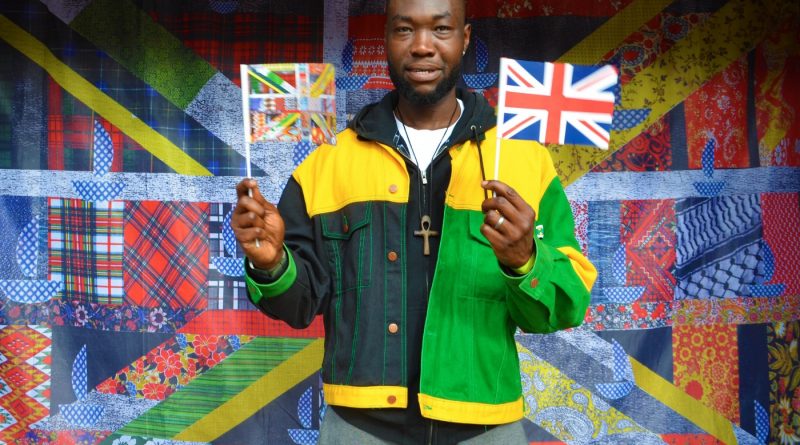

Racism in Jersey: Watch a 3-part series of television programmes Special Report: Race, Racism and the Channel Islands by Gary Burgess a reporter for ITV Channel TV that is being broadcast this week (Wed 17, Thurs 18, Fri 19 June). It features personal views and experiences of BAME islanders and also includes an interview with me about Jerseymen and slave ownerships.

Colonialism: Slave trade

Colonialism – what is it? How did the transatlantic slave trade embody and empower colonialism and imperialism? What are the distinctions between the concepts of colonialism and imperialism?

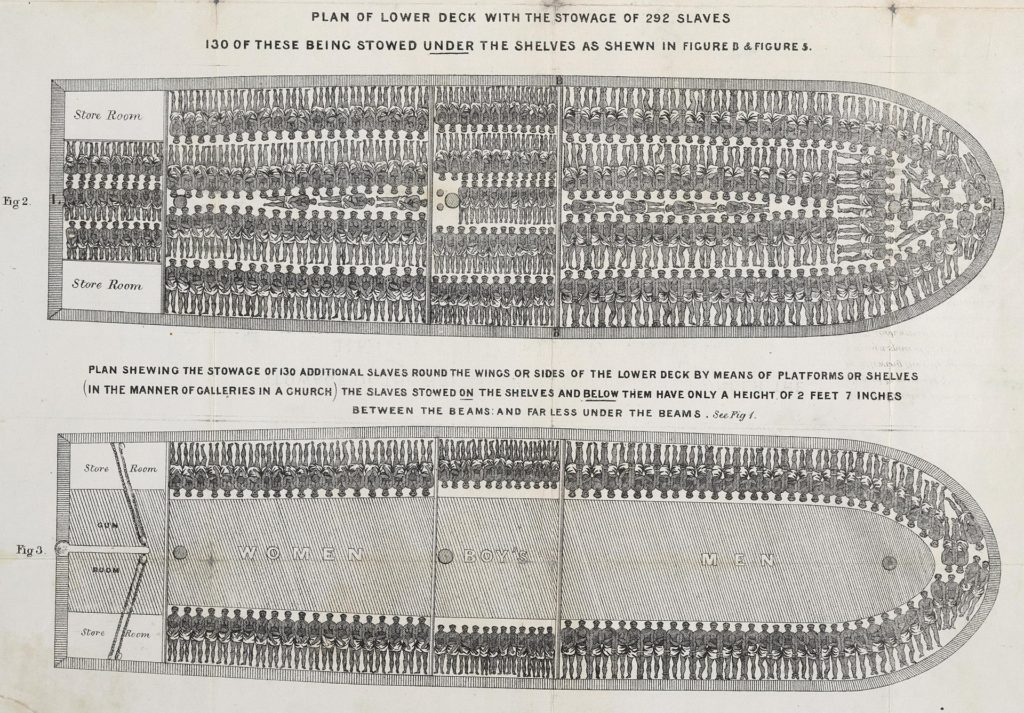

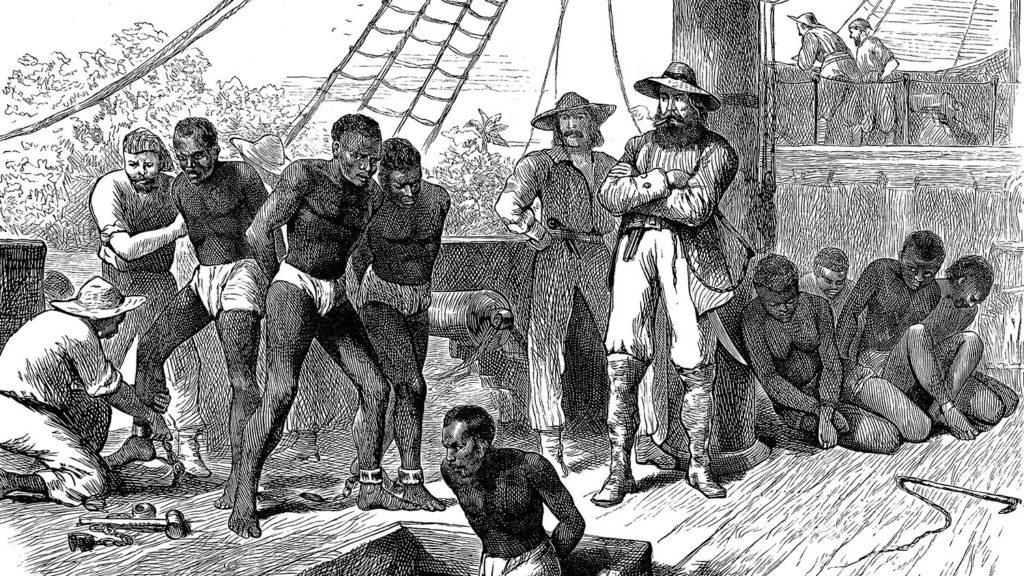

Colonialism is the practice of establishing territorial dominion over a colony by an outside political power characterized by exploitation, expansion, and maintenance of that territory. The indigenous populations suffered in the hands of the coloniser where they were subjected to confiscation of ancestral land, incarceration, hard labor and restriction in trading. To understand where racism came from we have to know about our colonial history, and in particularly enslaving Africans by forcibly removing them from their homeland and transporting them in ships across the Atlantic to the Americas to work on plantations in the new colonies occupied by European settlers. From the time Portuguese mariners began to ferry African slaves from 1500s onwards until the abolition of slavery by the British in 1833 somewhere close to 12 – 15 million black people had been trafficked. The kidnapping of Africans occurred mainly in the region that now stretches from Senegal to Angola. However, in the 19th century some enslaved Africans were also transported across the Atlantic from parts of eastern and south-eastern Africa. All the major European powers were involved in this enterprise, but by the early 18th century, Britain became the world’s leading slave trading nation. It’s estimated that British ships were responsible for the forced transportation of at least 2-3 million Africans in that century.

Here is a useful website for postcolonial studies and USI (Understanding Slave Initiative) which have many resources to help you understand the full legacy of slavery, incl some audio recordings of firsthand accounts. Listen to Equiano’s testimony of being kidnapped from his village and later sold at a slave market

For those of you who are really keen to learn more about Postcolonialism, please visit Dr McKinlay’s (Head of Media Studies) website here which includes proper academic references to some of the key thinkers and scholars on the subject, such as Edward Said, Louis Althusser, Chinua Achebe, Stuart Hall, Paul Gilroy and many others, as well as video and motion graphics that further illuminates issues at hand

On 25 March 1807, the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act entered the statute books. Nevertheless, although the Act made it illegal to engage in the slave trade throughout the British colonies, trafficking between the Caribbean islands continued, regardless, until 1811. The emancipation of slaves also happened at different pace in different colonies. For example, in British Honduras it wasn’t enforced until 1st Aug 1834 and some of the last places was Brazil (1888) – although not British dominion, but a Portuguese colony. In the USA, following the Union victory in the Civil War, slavery was made illegal upon the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865.

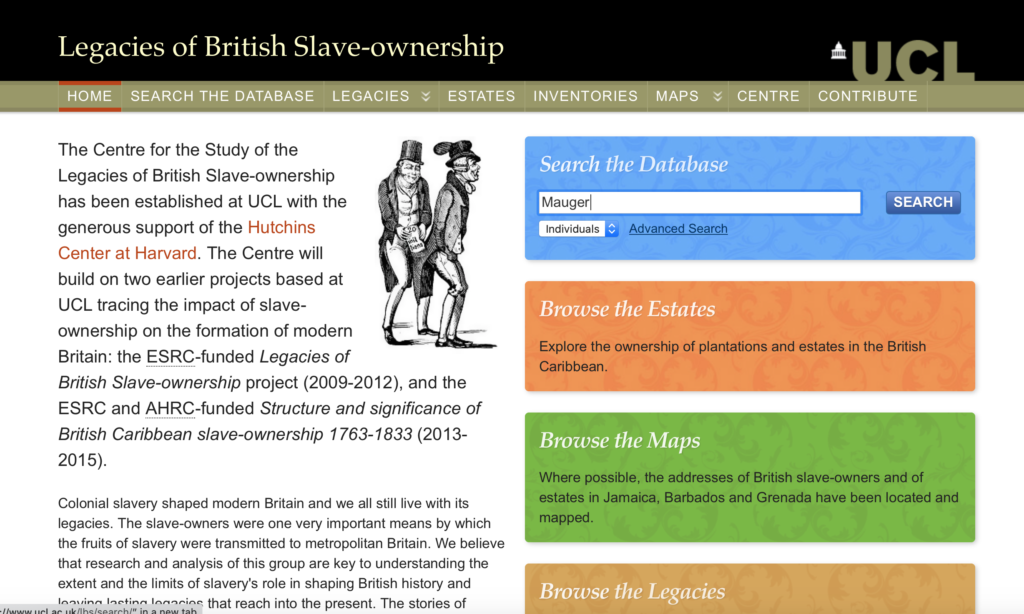

By 1833 the Slavery Abolition Act was enacted formally freeing 800,000 Africans who were then the legal property of Britain’s slave owners. The University College of London recently established ‘The Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership’ which includes a searchable database showing just how vast the extent of slave ownership was in Britain and how central it was to the economy at the time. In order to abolish slavery it was agreed that the slave owners would be compensated for their financial loss seeing 46,000 slave owners come forward to get their compensation. Until 2009 it represented the biggest bailout in British history with the UK government setting aside £20m in 1834, a sum that represented 40% of total government expenditure and the modern equivalent of between £16bn and £17bn today.

Modern day slavery. Today, although difficult to accurately determine, the Global Slavery Index estimates that there could be as many as 40 million slaves globally. With the overthrow of Gaddafi, of which Britain was complicit in, Libya has become an open market for the sale of African migrants and refugees in town squares and car parks. It has also become a major gateway for gangs profiting from the trafficking of refugees and migrants across the Mediterranean into Europe.

Local context: Jersey

What is Jersey’s role in all this? How are islanders acknowledging issues of racism and its own colonial history?

Reviewing the UCL database there is a total estimate of around £72,000 in compensation connected to Jersey at the time, which today — using the Bank of England inflation calculator — would roughly equate to £7,546,000. Read full article ‘Jersey’s Links to Slavery’ written by Ollie Taylor from 9×5 Media.

Another article, ‘A Respectable Trade or Against Human Dignity’ written by local maritime historian, Doug Ford provides further details of Jersey mariners involved in transatlantic slave trade. They include:

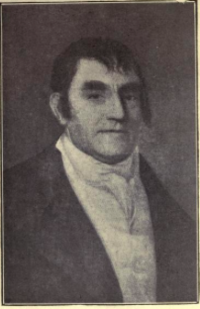

Josué Mauger from St John, Jersey, who built his fortune in the West Indian slave trade. Mauger had a fishing station, rum distillery and a large warehouse in the Halifax area in Nova Scotia, Canada and he opened a store in the town. He established a series of trading posts in Mi’kmaq territory (indigenous people of the Atlantic province of Quebec), and had a contract as a supplier to the Royal Navy. He was the largest shipowner in Halifax between 1749 and 1760, owning either wholly or in part 27 vessels. He also had a lucrative smuggling business with the French at Louisbourg, and when the Seven Years War broke out in 1756 he financed a number of privateering ventures. Evidence of Mauger’s involvement in the slave trade is an advert placed in the newspaper, the Halifax Gazette on 15th May 1752

“Just imported, and to be sold by Joshua Mauger, at Major Lockman’s store in Halifax, several Negro slaves, as follows: A woman aged thirty-five, two boys aged twelve and thirteen repectively, two of eighteen and a man aged thirty”. Further research needs to be carried out in Nova Scotia to ascertain exactle the scale of Mauger’s involvement before he returned to England in 1760. In 1768, he was elected to Parliament for Poole, a seat he retained with only a brief interruption until 1780. When he died, he left his money to his favourite great nephew, Philippe Winter Nicolle, who went on to set up his own merchant business in Jersey and build a new family home – No. 9 Pier Road, now part of Jersey Museum and known as Merchant House

Josué Mauger

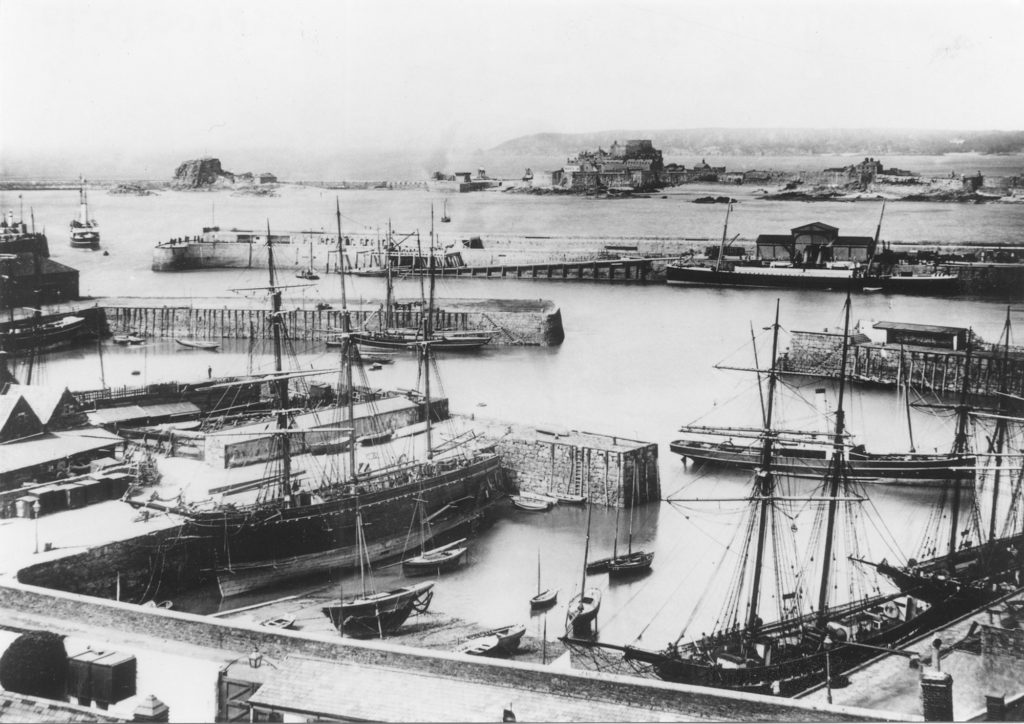

Merchant House,

9 Pier Road

Links between slavery and modern wealth in the UK are well established. Read article in the New Statesman here. The legacy of colonialism is wealth creation and the birth of capitalism. Stock markets were started when countries in the New World began trading with each other. While many pioneer merchants wanted to start huge businesses, this required substantial amounts of capital that no single merchant could raise alone. As a result, groups of investors pooled their savings and became business partners and co-owners with individual shares in their businesses to form joint-stock companies. Originated by the Dutch, joint-stock companies became a viable business model for many struggling businesses. In 1602, the Dutch East India Company issued the first paper shares. Read more here and watch this simplified short animation.

Recent protest against public statues of powerful men from our colonial past has sparked a worldwide debate about which histories should be told and what legacies should be celebrated. Major institutions around the world have been forced to acknowledge its past involvement in profiteering from the Atlantic slave trade. For example, both the Church of England and Bank of England apologise for historic slavery links (18 June 2020). It comes after insurance giant Lloyd’s of London and other well known high street banks, such as Barclays, HSBC, Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds acknowledge many former bank directors received compensation from the Slavery Abolition Act after slavery was made illegal in 1833. They have all pledged they will devote large sums to projects assisting minorities after being named in the academic database, Legacies of British Slave Ownership project set up by University College London.

Today Jersey’s economy is dominated by a financial services industry which accounts for over 50% of GVA (Gross Value Added – a measure of the value of goods and services) and almost 3/4 of all economic activity, if you include auxiliary sectors such as construction, hospitality and retail. The islands public services are dependent on the success and growth of Jersey’s primary industry. For example, the income tax alone, generated from the 13,500 strong workforce within finance are paying for the Government of Jersey’ education and health budgets combined.

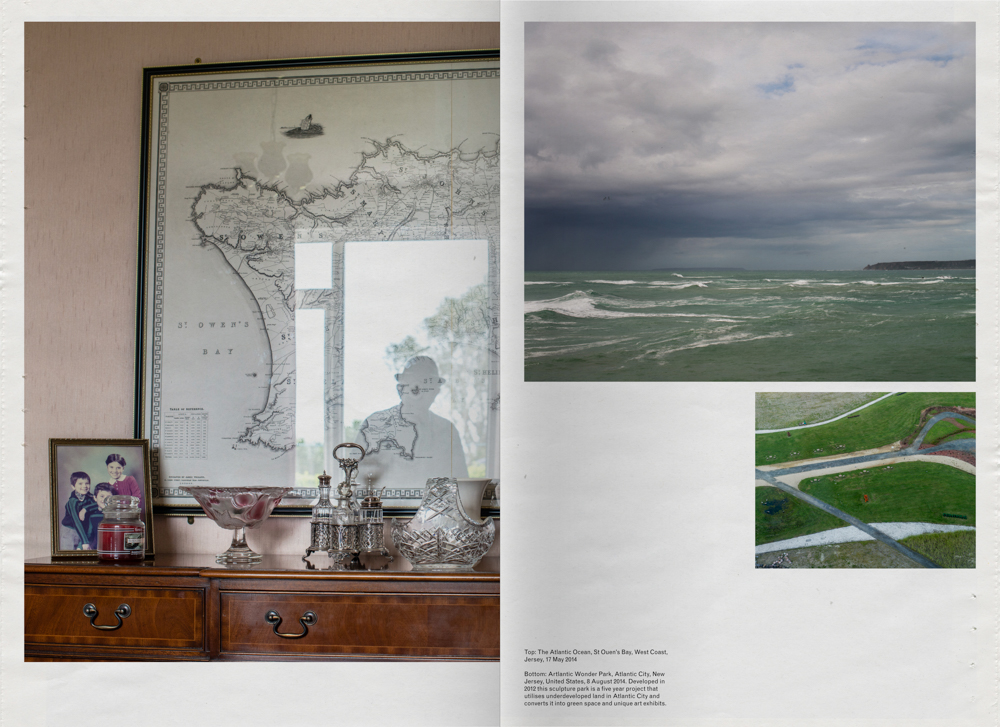

Since 2015 I have been working on MASTERPLAN – a research project using photography, film and archives to tell the story of Jersey’s contemporary prosperity as an Offshore Finance Centre (OFC), or what often is referred to as a Tax Haven. Globally there is a whole network of offshore jurisdictions and supporters of OFCs argue that they improve the flow of capital and facilitate international business transactions. Critics argue that offshoring is a way to hide tax liabilities or ill-gotten gains from the authorities, including money laundering. To understand how Offshoring is affecting the balance of power and wealth in the world with consequences for global stability and the environment, watch this film here.

In some of my other photographic work I have been developing a number of research projects about Jersey’s colonial history and maritime economy with links to slavery such as, Entrepôt and The Seaflower Venture. Essentially, I am examining through the prism of colonial and family history, how Jersey’s original wealth generated by the proceeds from the North Atlantic fisheries and merchant networks in the 18th and 19th centuries lay the foundation for the island’s economic growth and development in the 20th and 21st centuries as an International Finance Centre. Theoretically, my project Entrepôt is based around Rosemary E. Ommer’s structural economical analysis of the Jersey-Gaspé cod fishery which reveals a functional three-pointed trading system in what she refers to as a ‘merchant triangle’ with production in Canada, management in Jersey and markets in the Mediterranean, the West Indies and Brazil. Her central question in her book is: ‘How did the cod-fishery, functioning as a commodity trade, shape the economic development of the metropole that managed it and the colony that produced it.’ (Ommer in Outpost to Outport: A Structural Analysis of the Jersey-Gaspé Cod Fishery, 1767-1886)

In 2019 I spend 6 weeks in Belize and Honduras and in the colonial records I uncovered interesting details regarding several Jersey merchants operating as mahogany cutters and their slave populations. I also surveyed the colonial landscape and explored several estates belonging to Jerseymen and the communities that their mahogany works fostered. Additionally, I tracked down descendants currently living in Belize and the Bay Islands of Roatan and Utila (Honduras) with direct ancestral links to Joshua Gabourel who arrived here from Jersey in 1787. Some of this material includes:

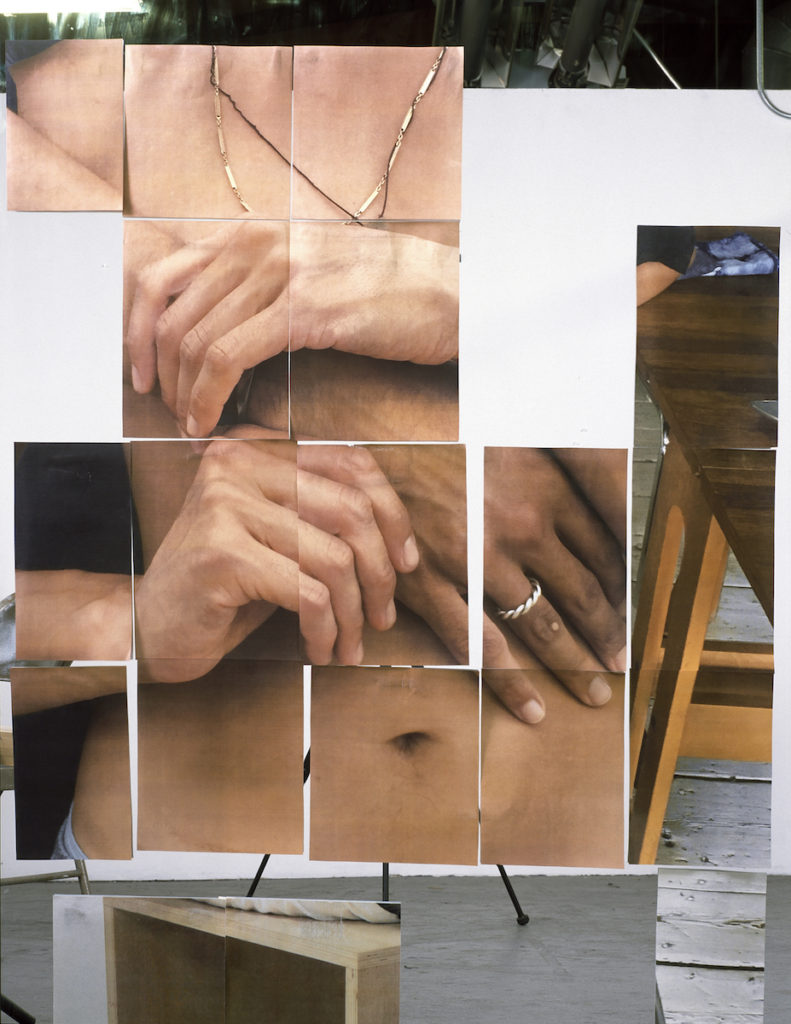

- Census records and Slave registers from Belize with names of Jersey merchants and their households

- Inventory and Appraisement – list of land and property owned where ’negroes’ are listed alongside, goats, cattle and farm equipment etc

- Invoices of buying and selling slaves.

Inventory and Appraisement

Inventory and Appraisement

Manumission of slave named Lucky

Listing slave population owned by William and Joshua Gabourel, sons of Joshua Gabourel. © Belizean Archives and Records Service. Belmopan, Belize

If you wish to learn more about the mahogany trade in Central America, and in particularly, British Honduras, read this essay Furnishing the Craftsman: Slaves and Sailors in the Mahogany Trade by Dan Finamore,Curator of Maritime Art and History at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. It gives a very detailed account of extracting mahogany wood from its dense forests under strenuous hardship of African slaves and shipping it to North America and Europe (including Jersey) and be turned into fine bespoke furniture to adorn the large mansions of the merchant class known as ‘cod-houses’ (maison terre-de-neuve.) Mahogany and other exotic hardwoods were also used successfully in the growing shipbuilding industry in Jersey for decorative purposes.

For centuries Jersey’s maritime economy dominated island life and many merchants were engaged in the Atlantic trade, referred to as the ‘merchant triangle’ with commodities of manufactured goods and agricultural products exchanged in different outposts in the British Empire and other European colonies in the Caribbean, South America and Mediterranean. However, Jersey’s financial success derived from the North-Atlantic cod-fisheries established first in Newfoundland late 16th and 17th centuries and later in Gaspé in the province of Quebec in 18th and 19th centuries.

Charles Robin

Salted cod drying on rack Gaspé

Jersey’s colonial past is linked indirectly with slavery as merchants and shipping were part of the supply chain of goods and products in the transatlantic trade. One of Jersey’s premier cod-merchants was Charles Robin who founded Charles Robin Company in 1766 (second oldest incorporated firm to be founded in Canada which only ceased operation in 2006 albeit under different ownership). Robin produced two salted cod-products called ‘green’ and ‘yellow’. Green was a cheaper cured fish and was sold to plantations in the West Indies as a source of protein to feed slave populations. Yellow, was marketed as a premier product and sold to markets in Brazil and southern countries of Europe, such as Portugal, Spain and Italy with their large Roman Catholic populations having a great demand for fish for fast days. From ports in Lisbon, Cadiz and Naples merchants traded cod-fish for other products such as salt (used in the curing process), wine, spirits, fruits and spices which they brought back to Jersey and British ports before returning to Canada. The maritime networks were complex and often financed from London. Read another article here from Jersey based critic, Ollie Taylor Fish, Finance and Slavery.

Voyage patterns

Commodity flow chart

If you look up shipping news in old Jersey newspapers La Gazette de Jersey or La Chronique de Jersey ships would leave St Helier Harbour with supplies to slave stations in West Africa, such as the notorious Cape Cod Castle on the Gold Coast of Ghana. For example, on 8th June 1854 Newport, a 106-ton schooner brig owned by F Le Sueur, jnr, P Le Sueur and JF Le Sueur, mastered by sea captain, Charles Philippe Hocquard left port bound for Ambrez, Angola. On the ship’s manifest (a customs document listing the cargo, passengers and crew) were 25 cases of muskets, 20 cases of knives, five cases of hatchets, one case of bells and padlocks, to be delivered to a Senor Francisco Antonio Florese, who was known as a slave trader. On 21st September 1854 she was stopped and searched by HMS Philomel and taken to St Helena, where she was condemned in the Admiralty to be sold.

In 2015 I published Atlantus together with Dr Gareth Syvret (former photo-archivist at Société Jersiaise) which is a transoceanic photography project about the connected history between Jersey and New Jersey, prompted in part by the 350th anniversary in 2014 of Sir George Carteret naming of the State of New Jersey, USA after Jersey his island home in 1664.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/jerseyeveningpost.mna/PZ4YF43C4RDDNGOIV6JSNB4RXY.jpg)

In 2014 a public statue of Sir George Carteret was unveiled in St Peter to commemorate his achievements in relation to the 350th anniversary of the state of New Jersey. Sir George was a prominent investor and consultant in the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading Into Africa, which was a major player in trafficking slaves from Africa as well as gold and ivory. Between 1662 and 1731, the Company transported approximately 212,000 slaves, of whom 44,000 died en route. By that time, they also transported slaves to English colonies in North America. Its profits made a major contribution to the increase in the financial power of those who controlled the City of London. Sir George received a dividend until his death and his son James Carteret commanded one of the slave ships, Speedwell with 302 Africans on board in the early years (1663-64) of trading from Benin to St Kitts in the Caribbean.

Please read the latest article by Jersey independent reporter, Ollie Taylor (Nine by Five Media) The whitewashing of George Carteret and watch a video below of its unveiling in St Peter with a commentary by the former Constable John Refault who describes Sir George Carteret as a hero, ‘Jersey’s greatest son’, one of “Jersey’s great figures” and a role model for youngsters.

It is true that the biography of Sir George Carteret (b. 1610 d. 1680) include many extraordinary deeds such as commandeering ships in the Royal Navy and rising quickly through the ranks to become the Comptroller of the Navy in 1641 and eventually Vice Admiral. Between 1643 and 1651 he was both appointed Lieutenant Governor and Bailiff of Jersey. But it was his loyality to Prince Charles II, who was exiled in Jersey twice during the English Cicil War after the death of his father King Charles I that propelled him to power and influence. After the restoration of the monarchy he was granted lands in the new British colony in North America, including the Carolinas and a territory south of New York, which he named New Jersey after his island home. There are some people who only wish to remember this part of his life, but there is a growing demand that his links with the Royal African Company and the Atlantic slave trade must be included in the historical records. It’s important to recognise that history is never fixed and new research, new interpretations are made continuously as new material emerge and different scholars examine the archives. There are many different histories depending on who is telling them and it is your duty as future citizens to examine all points of view and analyse claims and counter-claims.

Portrait of Sir George Carteret by court painter, Sir Peter Lely

Statue of Sir George daubed in white paint in St Peter

The statue pulled down in Bristol last week was of Edward Colston who was the Deputy Governor in Royal African Company, which succeeded The Company of Royal Adventurers Trading Into Africa in 1672 with a new and broader royal charter than the old one, which included the right to set up forts and factories, maintain troops, and exercise martial law in West Africa, in pursuit of trade in gold, silver and African slaves. Read article here in The Guardian about Colston statue in Bristol.

The decision to erect the statue was questioned by Deputy Montfort Tadier, who as Minister for Culture said that it was a different case to the Edward Colston statue because that had been put up in Bristol around 120 years earlier, during the closing years of Queen Victoria’s reign. He has lodged a proposal Jersey and The Slave Trade to discuss how the island deals with its past at the next States Assembly.

There was also controversy when part of the International Finance Centre was named Trenton Square after the capital of New Jersey, which was itself named after trader William Trent, who had links with slavery. Read more here

In the JEP last Saturday (13 June 2020) there were 3 Opinions published by columnists, Susanna Rowles, Tom Ogg and Gary Burgess. Very diverse points of view about how to address the issues of racism and the wrongs of the past, but all comments written by ‘white’ people. Where is the representation of BAME (Black, Asian and minority Ethnic) voices?

Read an islander who is mixed race talk about white privilege and another article in the Bailiwick Express that urges Jersey leaders to dismantle institutional racism in the work place and wider community at a protest for racial justice at People’s Park on Saturday 6 June.

Tasks

BLOG – evidence of the following using a combination of images, text and hyperlinks to online sources. Publish post on a regular basis. You should aim for 2-3 blog posts per week. Mr Cole and myself will monitor and provide feedback online in comments on the blog until more regular lessons are timetabled.

RESEARCH

- Global context: Describe racism and how racial discrimination over time has led to Black Lives Matter movement. (1 x blog post)

- Colonialism: Explain what it is and how the slave trade evolved as an instrument of power and suppression of enslaved people from Africa. (1 x blog post)

- Local context: Reflect on issues of racism and Jersey’s link to colonial history and slave trade. (1 x blog post)

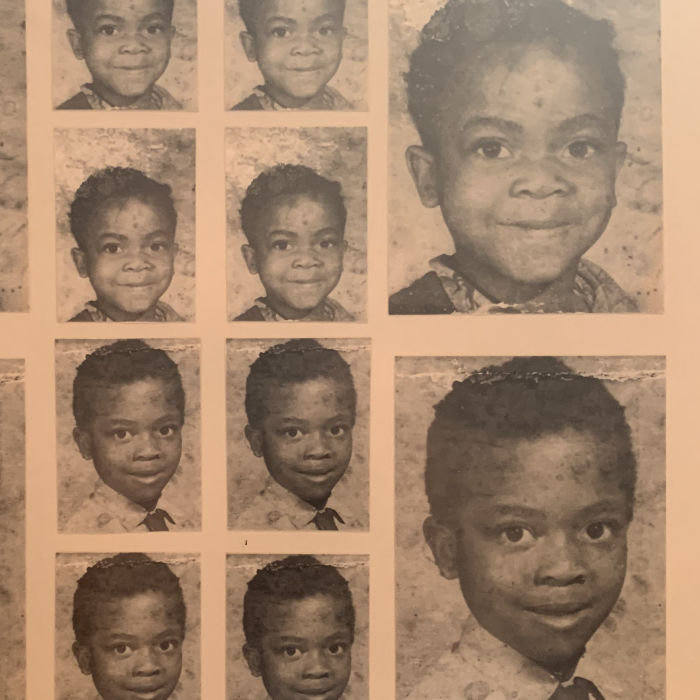

- Collect found images, graphics, texts and slogans from a variety of sources from the internet and newspapers clippings for further experimentation. (1 x blog post)

- Artists References: find inspiration from at least two artists, explain why you have chosen them, analyse key works and include hyperlinks to online sources. (1 x blog post)

RECORDING:

- Photo-shoots: (200-250 images)

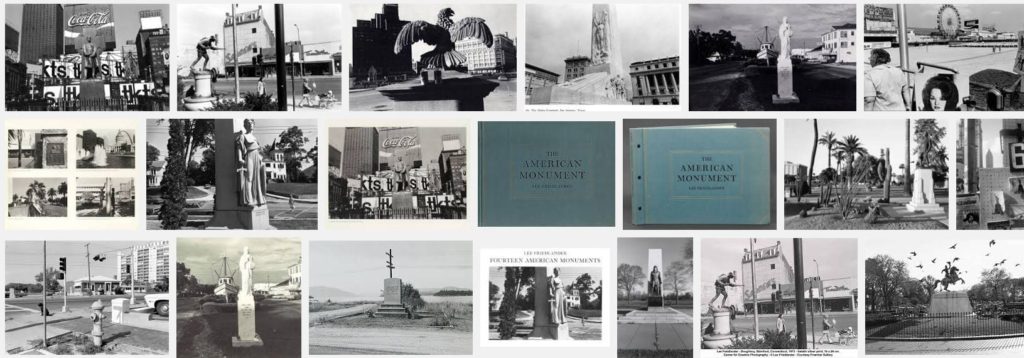

- Jersey public statues, monuments and squares.

- Focus on one, or multiple sites & explore how it functions socially ie. how the public use and interact with the statue and its location. Frame details and abstract compositions.

- If you have any other ideas about images you want to make in response, please go ahead as long as you can link it to the themes.

- For example, you could explore mixed identity, self, race, skin, masks, feminity, masculinity etc in a series of self-portraits or use a model.

- Editing: process, adjust and select a 10-12 images for further experimentation.

Sites: Royal Square, Victoria Park, People’s Park, Parade Gardens, Liberation Sq, Weighbridge, West centre, Millenium Park. St Peter (next to pub)

EXPERIMENTING:

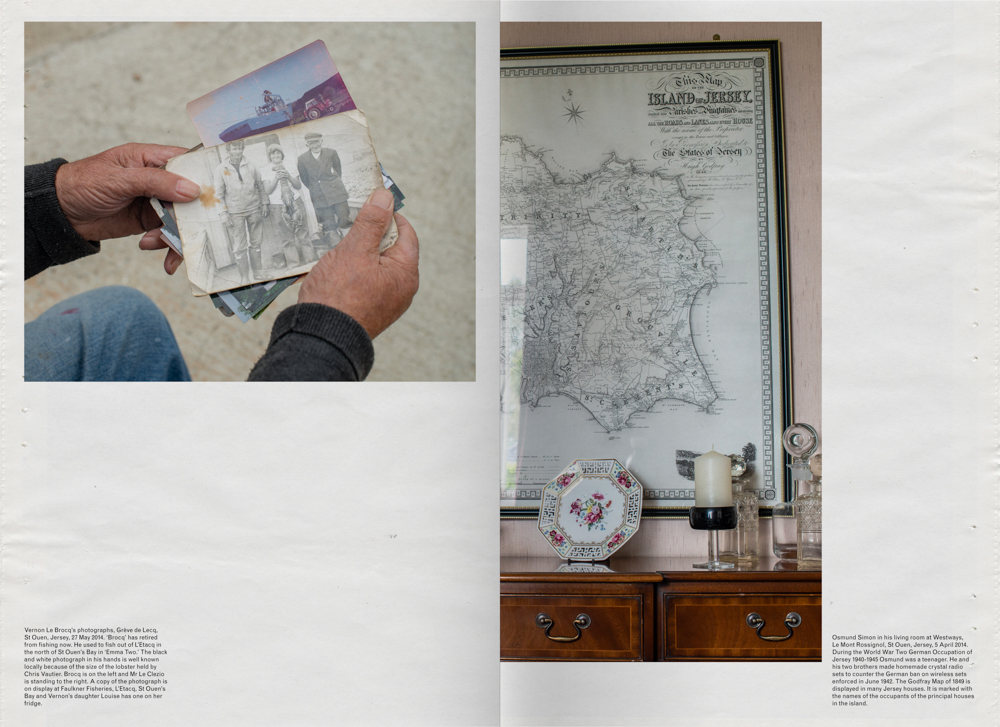

- Montages: Create 3-5 montages/ collages using both digital (Photoshop) and analogue (paper, print, scissors, glue) techniques using a combination of your own images, found images, text and slogans.

- Monument: Create your own digital public statue, Who would you consider worthy of adoration and recognition? Use a combination of same material and techniques as above, or create a 3D model and photograph in a series of still-life images

- Protest: If you were to organise a protest what issues and causes would you fight for? Design 3 different posters using a combination of slogans, graphics, images and typography.

Inspirations

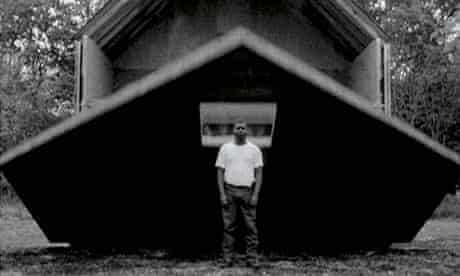

Mohamed Bourouissa

Tracy Moffatt

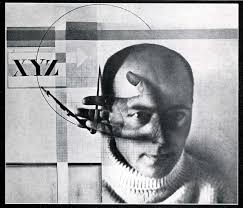

Peter Rodchenko

El Lissitzky

Steve McQueen

Lorenzo Vitturi: Dalston Anatomy

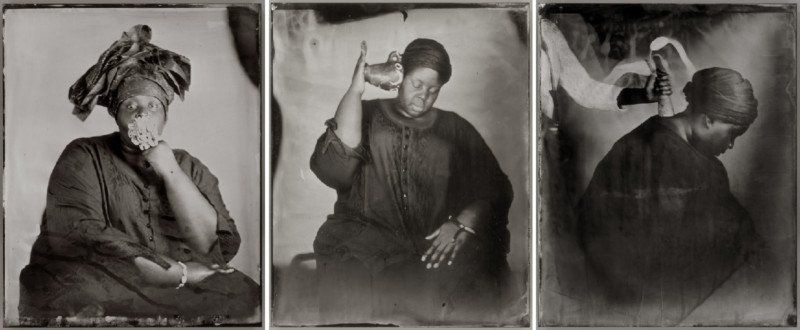

A couple of recent exhibitions in London on gender and race identities; Masculinities Liberation Through Photography at the Barbican at African Cosmologies

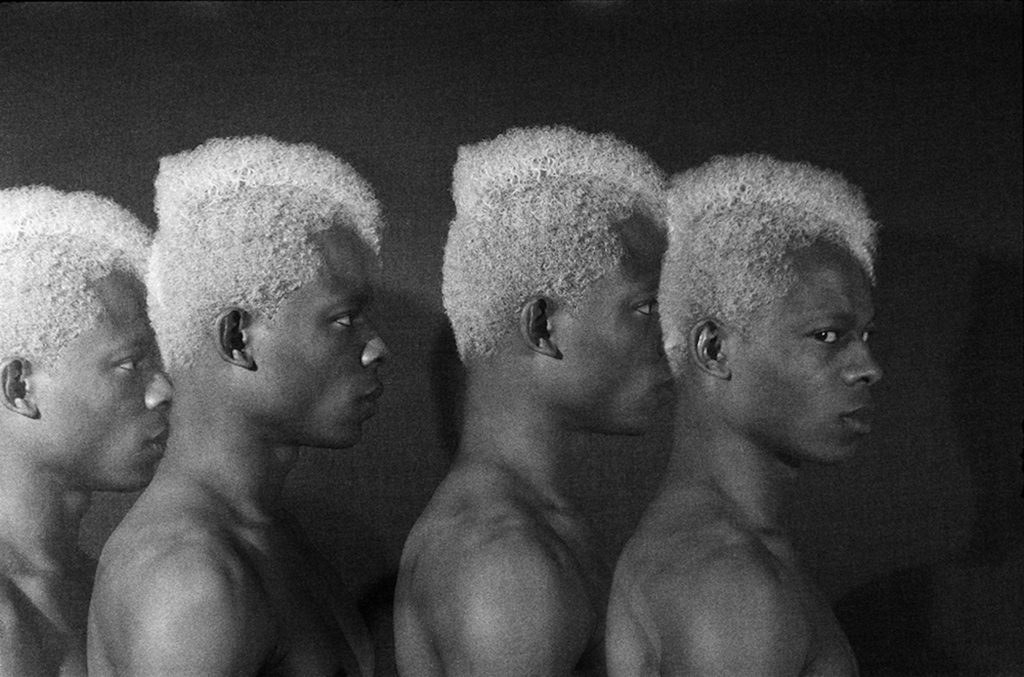

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Four Twins, 1985

Essay

TITLE : “What makes an image iconic?“

Primary Source: Read this article by Susan Bright and answer the following question; What makes an image iconic?

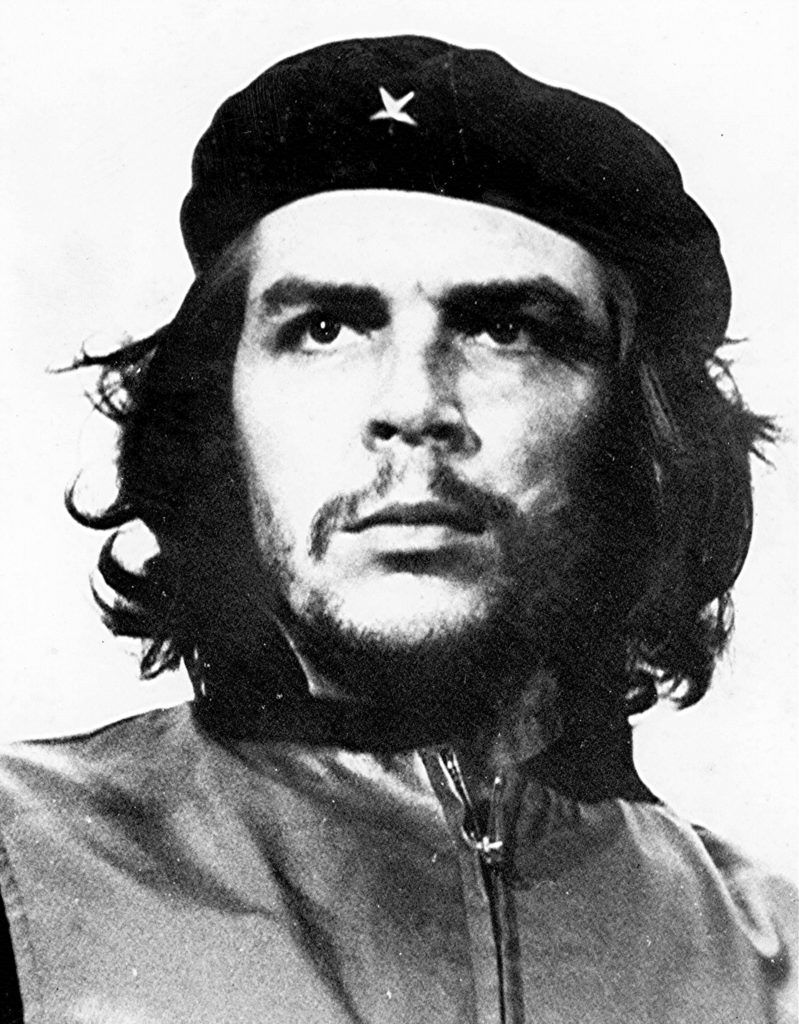

Alberto Korda

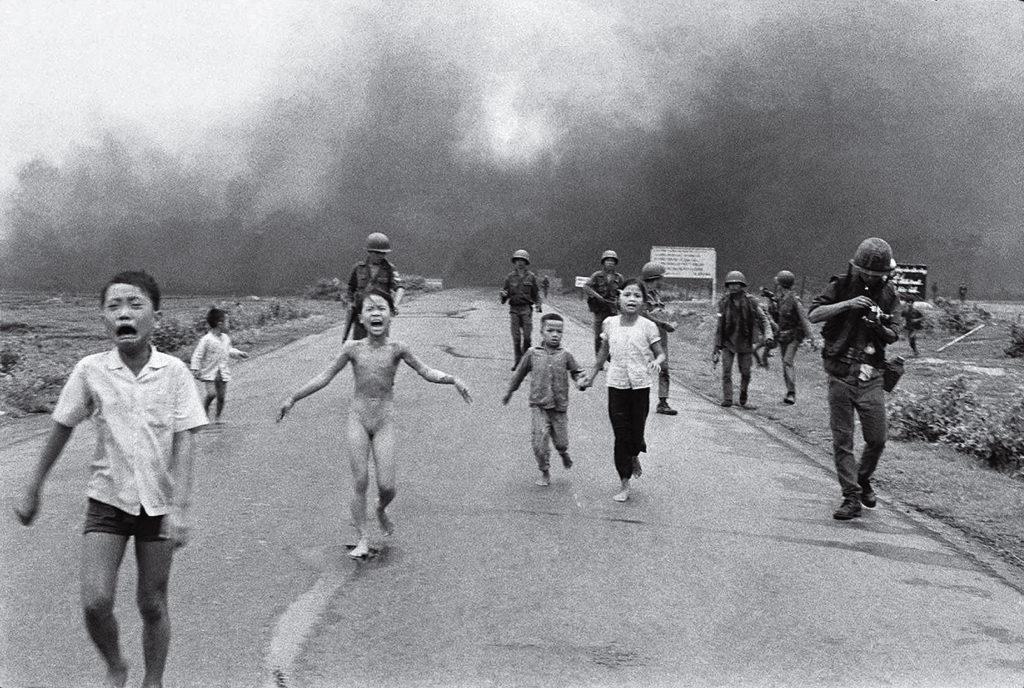

Nick Ut

Kevin Carter

Follow these instructions:

- Write 1000 word essay

- Read texts in detail, make notes and identify 3 quotes

- Use examples mentioned in texts and compare with the image above (BLM protester carrying white man to safety)

- Construct your own interpretation of the photograph by applying the theory and critical thinking learned from the text you have just read.

- Incorporate the 3 quotes above into your analysis and interpretation of the image and make sure you comment on the quotes, either for or against in developing a critique and informed argument.

- Read and reference both from primary and secondary sources

- 1000 words = intro, analysis, discussion, conclusion – easy

- Make a photographic response: Can you make an iconic image?

Secondary sources:

Read How to make an iconic image

Stuart Franklin’s article: Why there is no such thing as an iconic image.

Another article here: Scientists have uncovered exactly what makes a photo memorable

DEADLINE: Wed 1 July