Compare how Cindy Sherman and Phoebe Jane Barrett challenge gender stereotypes in their work

“Our familiarity with cinema contributes to the ingrained ideas about beauty and gender in our visual language, so it is not surprising that the medium has influenced so many self-portraits…” (Bright, 2010, 11)

Introduction:

The representation of gender roles and stereotypes has been a popular concept within art and photography throughout the history of both art forms, but it is only recently that artists have begun to directly challenge these stereotypes in their work. The deeply ingrained gender stereotypes found in society, some more subtle than others, have been present throughout history, and alongside how our views on gender has changed. The process of societal change in views and opinions on gender has been slow, however, the turn to focus on gender studies in photography during the 1990’s (heavily influenced by philosopher Judith Butler’s 1990 book, “Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity”) provided a new outlook on the way people viewed traditional gender roles and stereotypes. Photographers began to turn towards more abstract depictions of gender, with the focus on breaking, rather than adhering to gender roles. The move towards gender identity as a photography focus altered the way in which identity-based art was represented, with “a striking visible popular interest in gender presentation and sexuality in the 1990s [intersecting] with an explosion in the production of art” (Blessing, 1997, 7) .In my personal study I wish to be able to show how these changes and developments in gender stereotypes have changed in the 20th and 21st century, from more traditional gender roles and ideas to our current understanding of the development of many different gender identities. Out of the many artists who explore gender stereotypes in their work, I have chosen to focus on photographers Cindy Sherman and Phoebe Jane Barrett, who both represent gender roles in the 21st century, using different methods and approaches. I have chosen to study these artists, because I believe both Barrett and Sherman convey strong context and meaning through their images, while at the same time producing work that really engages the viewer, and allows for a dialogue to be opened about the way that society and the media portrays versions of both men and women, that are not true to real life, thus forcing people to adopt stereotypical behavior in order to fit in to a social norm. In order to compare these two artists, I will examine both similarities, such as the concept of drawing attention to gender stereotypes and their representation, and differences, such as their different visual portrayals of these stereotypes and the way in which they approach their work. Both artists approach towards challenging historically rigid and strict gender roles and stereotypes can be seen as an attempt to redefine what society sees as acceptable for each gender, and bending the rules in order to allow individuals to express themselves freely without being judged. Phoebe Jane Barrett acknowledges the consequences of these strict barriers to individual expression, and is quoted as saying, “I wish that gender created less of a divide between people” (Barrett, 2019). I intend to respond to the work of Sherman and Barrett by showing both subtle and overt examples of how gender has developed and changed through time, and to do this I will be incorporating strong and obvious examples of breaking gender roles when it comes to stereotypical masculinity, while also using multiple examples of the subtle ways in which femininity is rejected by modern women, choosing instead to follow their own version of identity rather than society’s ideas.

Historical context:

Photography as it is currently known was developed in the form of the daguerreotype, by French photographer Louis Daguerre in 1839, in order to scientifically record true to life images as they were in the real world. The daguerreotype paved the way for the advancement of photography, and is revered even in the modern era by photographers such as Adam Fuss as allowing the viewer to “see what has never been in a camera. Life itself is the image” (Fuss, 2010). The daguerreotype also allowed, for the first time, for someone to manipulate the contents of an image in order to suit their ideas. In the words of authors of the book “Photography Decoded“, Susan Bright and Hedy Van Erp, “The daguerreotype had the aspirations to both the realistic and the theatrical, as well as the commercial” (Bright, S. and Van Erp, H. 2019; 17). With the development of technology and the camera becoming a more widespread devise, the development of different movements in art and photography began to occur. An early movement in photography (appearing from 1860 onwards) was Pictorialism, which rejected the use of photography as a way to scientifically record objects realistically, and instead opted to focus on emphasizing the tone, beauty and overall composition of images, presenting them more as an art form than a method of recording data. A key individual who helped to shape the movement was photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, who’s work during the late 18th century was focused around portraying the inner workings of her subjects, often using children looking wide-eyed into the camera to emphasize the focus on exploring the concepts of dream, the unconscious and imagination. Early photographers such as Cameron helped to develop the movement of Pictorialism, and although their work was often rejected by critics of the time due to its unfocused, ambiguous appearance, their work on the movement was essential for the development of the understanding of photography as an art form. The step towards focusing on the beauty and composition of images led to the development of aesthetically focused and decorative images, emphasizing the contextual meaning of the subjects and concepts within the image. The work produced by photographer Phoebe Jane Barrett follows along the ideas and methods of Pictorialism, with her work often displaying a soft focus, and allowing certain areas of the composition to be draw the attention of the viewer the most. The beauty of the subjects in her images are emphasized as the vulnerability and fragility of their masculinity, and is purposely presented as a major part of the concept of the image. Photography continued to develop as an art form through the 19th and 20th century, and during this time the ways in which photographers expressed and portrayed their own opinions on political, social and human issues changed, as it became easier to edit and manipulate images to suit the need of the photographer. A movement that became popular during the latter half of the 20th century was Postmodernism, a movement which incorporated themes from a range of previous movements (including Modernism) and focused on the ideas of surrealism, bricolage and parody to present the ideas and beliefs of the photographer. Postmodernism was originally a response to the modernist movement, popular in the late 19th to mid 20th century. Contrasting Modernism, which focused on the visual elements of an image, praising the photographer for their ability to create beautiful images with their artistic skills, the Postmodernist approach looked more at the concept and context of the image, rather than it’s physical appearance.

In Postmodernism, the idea matters more than the work itself, allowing the photographer room for a lot of creative artistic freedom when it comes to the subjects. Postmodernist artwork is often produced for the novelty factor, allowing the viewer to enjoy a visually pleasing experience (incorporating bold colours, shapes, and wild concepts), while subtly hinting at a deeper meaning. Cindy Sherman’s work can be considered to follow the characteristics of Postmodernism, with her bold and colourful self-portraits parodying how society views women and how femininity is represented in the media. The exaggerated appearance of the subjects providing a visually interesting experience to the viewer, while at the same time hinting at the deeper meaning of hiding ones true appearance behind a mask that society would find more socially acceptable. Sherman’s work challenges the representation of women in the media, and forces the viewer to consider the ridiculous way in which many women have their features overplayed and portrayed in social media. Sherman’s work depicts parodies of an important feminist theory that has become popular in modern work, known as the “male-gaze”. The “male-gaze” refers to the way in which women are presented from the perspective of heterosexual, masculine perspectives, as sexual objects that are included in order to please the male viewer. This concept in the art world has remained prominent since medieval paintings, and the term “male-gaze” itself was coined by film critic Laura Mulvey in her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”(Mulvey, 1989). Mulvey’s essay touches on the concept of the “male gaze” in cinema, describing that, “In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.” Here, Mulvely gives a perfect definition of how the “male-gaze” influences the display of women in the media; a concept that Sherman is able to hint at in her own work, displaying the characters in her scene as over the top and caricature-like versions of women, highlighting the absurdity of the way women often appear in media. Although “through the male-gaze” has been the most prominent way in which women have been depicted in the media throughout history, in more recent years there has been effort to fight back against this one-sided representation of women, with exhibitions such as the 1995 “Rose is a Rose is a Rose: Gender Performance in Photography” providing an outlet for photographers to break the boundaries of gender norms, as it “offered ways to elude the heterosexist, patriarchal male gaze and speak to more diverse desires” (Blessing, 2017, 98). This move from a sexist, one-sided method of representing women in photography, to a more inclusive, diverse way of incorporating all gender identities and gender expressions, has allowed for modern feminist photographers such as Sherman to break the boundaries of social acceptability and gender norms in their work.

Cindy Sherman:

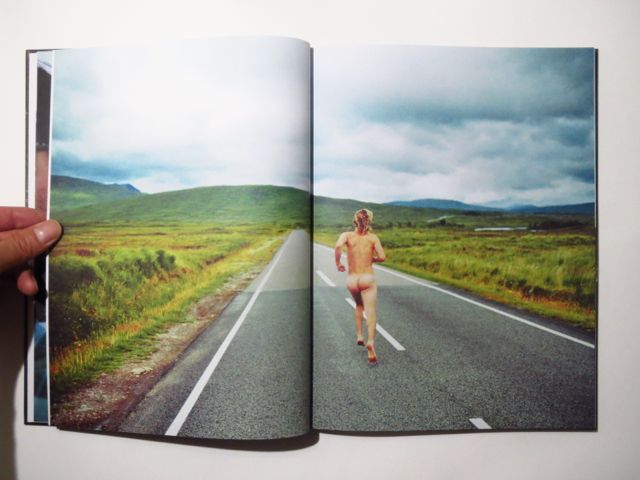

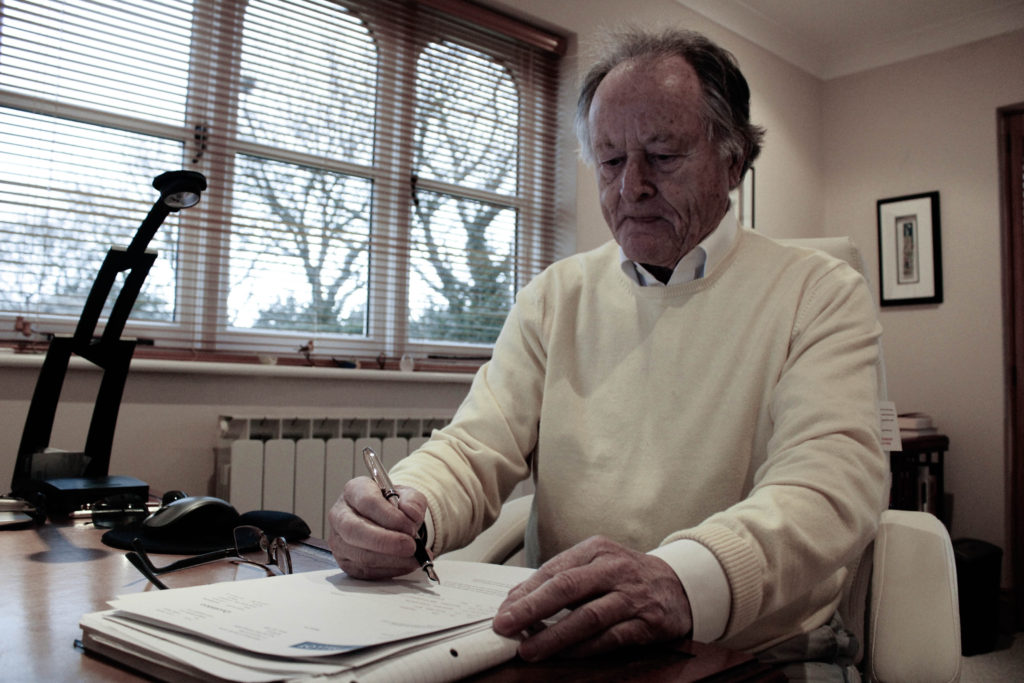

Cindy Sherman’s approach to photography did not begin with the boldness and daring as her more current work. Sherman originally took part in creating film stills during the 1970s and 80s, with her work involving black and white self portraits, where she depicts different ideas and concept of women of the time. Her work then became progressively more bold, with her project Centerfold, (1981), in which she produced one of her most recognizable pieces of work, Untitled #96. Throughout all of her work, Sherman has focused on the theme of personal and individual identity, with the overarching idea of her work being the way that we as individuals project and present our identities to the outside world. Her work has been met with praise from many critiques, applauding her use of self-portraits to convey a number of identities which are all based in the same theme of hiding and exploring female stereotypes. Popular opinion of Sherman’s work can be summed up in the words of art critique Laura Cummings; “Sherman has by now invented more than 600 personae; every one of them is a recognizable type, to some extent, and yet also an individual” (Cumming, 2019). Her work reflects the vulnerability of the subject within the images, with her piece Untitled #92 reflecting a distressed and scared self portrait of herself in a vulnerable position. Her work reflects the vulnerability of those who express their individual identity, and by taking self portraits, Sherman is able to both remove herself from her work through hiding her identity, while also remaining very much involved in the practicalities of her photography. Sherman herself believes “I feel I’m anonymous in my work. When I look at the pictures, I never see myself; they aren’t self-portraits. Sometimes I disappear.” (Sherman, 1990). Her current work revolves around making extremely eye-catching and striking images, while at the same time providing a narrative behind the image which helps to engage the viewer, and forces them to realize the contextual and conceptual realities of the image. Sherman herself believes that “people are more apt to believe photographs, especially if it’s something fantastic. They’re willing to be more gullible. Sometimes they want fantasy” (Sherman, 1985), which allows for the explanation as to why she decides to make such expressive images. In the above image, (which remains untitled but is often refereed to by Untitled (self-portrait of sun-tan 2003)) Sherman is focusing on drawing the viewer in using bright and eye-catching colours, making use of deep oranges and an extreme layer of orange sun tan across the body of the subject in order to create an incredibly dramatic, satirical example of a tourist woman. The colours in this image are what draw the eye initially, however the concept behind the image revolves around portraying the way in which women (in this case, a tourist) in the modern era are portrayed in such an extreme way in the media. Rather than using overt examples of the unrealistic standards of women in the media, (and the struggle of maintaining and developing ones identity in general), Sherman focuses on leaving her images very open to the interpretation of the viewer, allowing the viewer to decide what the image represents in terms of female identity and the way we are perceived in general. Sherman’s goal was for there to be “hints of narrative everywhere in the image so that people can make up their own stories about them” (Sherman 2016), allowing the viewer to develop their own understanding of the concept of identity and gender with guidance from the image.

Phoebe-Jane Barrett:

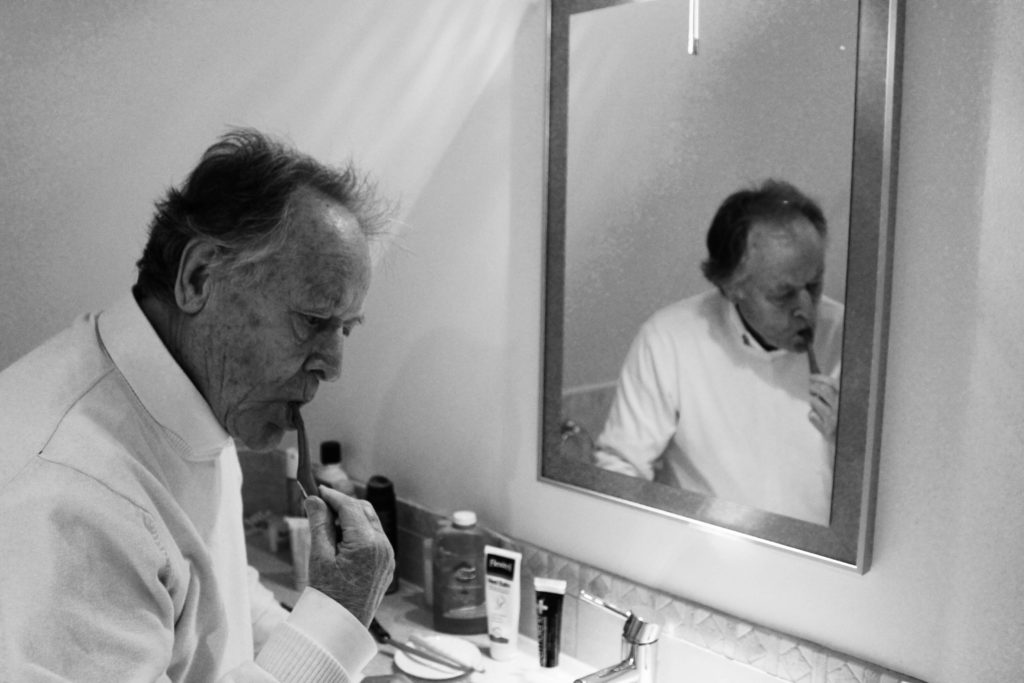

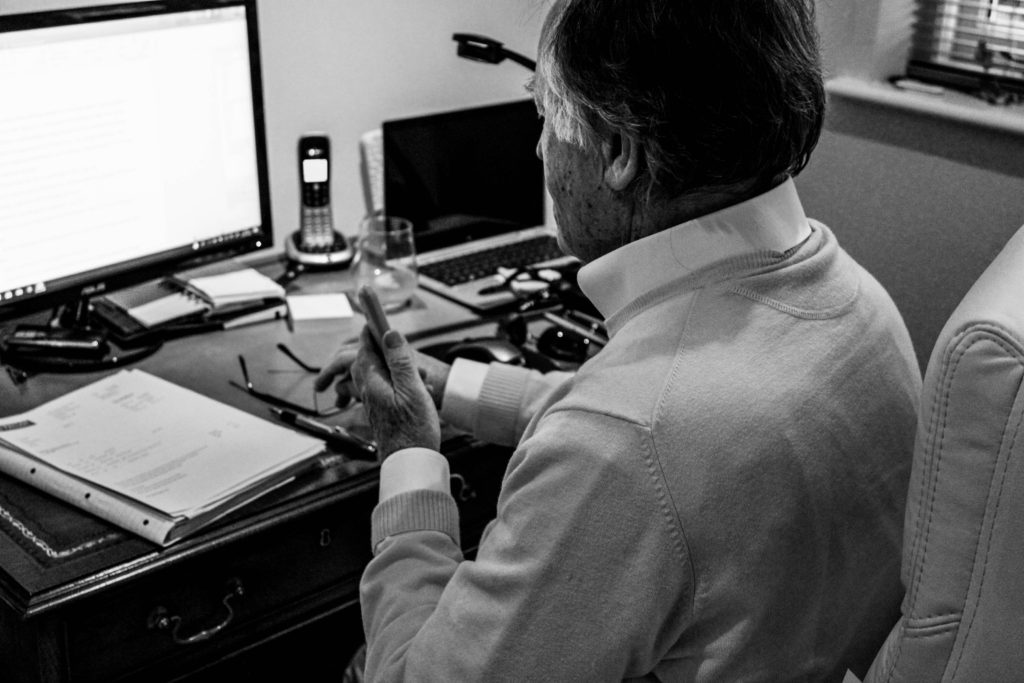

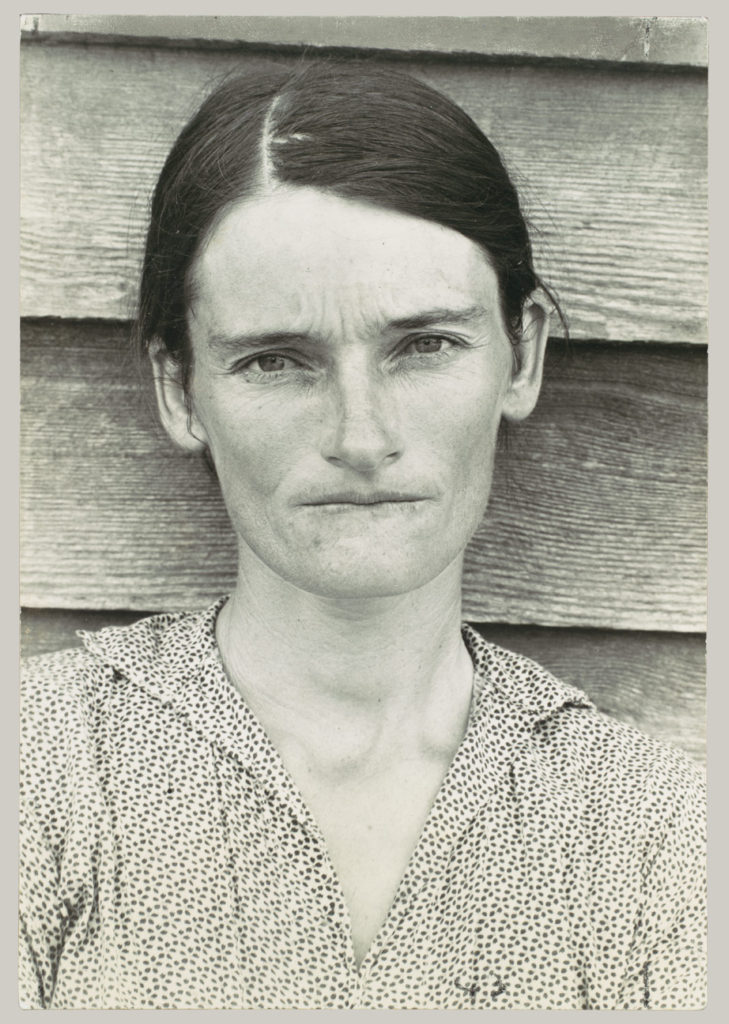

While Sherman takes a direct approach towards highlighting the distorted way in which women are portrayed in the media, in order to elicit a strong emotional response of shock or intrigue from the viewer, Barrett instead takes a much more subtle and soft approach towards her representation of male vulnerability. Barrett’s work has an overarching sense of humanity to it, with her photography often depicting the intimacy of human relationships and connection, focusing on presenting societies more hidden and controversial topics. Barrett found photography as a way to express her own opinions on social situations, as it allowed her to “challenge myself and push myself forward, collaborate more and focus on a variety of subjects and genres.” (Barrett, 2019). A more controversial topic that Barrett approaches in her work, is the concept of male vulnerability, and the reality that “the stereotypes around masculinity are damaging to men, women, and to society as a whole.” (Barrett, 2019 (2)). In order to portray this topic, Barrett took a delicate approach, using male subjects in vulnerable and stereotypically feminine poses and situations to highlight the truth that men experience vulnerability and emotion the same way as women, yet are expected to hide this in order to meet society’s definition of “masculinity”. The above image depicts a stereotypically masculine-presenting male subject, with his facial hair and low brow presented as the centre of the image, drawing the viewers full attention to the fact that the subject is male. However, this presentation is contrasted with the situation the subject finds himself in, lying on the lap of an unidentified subject, who holds the man comfortingly. The male subjects blank, glazed over expression gives away very little personal emotion, therefore forcing the viewer to gain all of their contextual information from the visuals of the scene around him. The subjects position reflects that of a small child seeking comfort from his mother, or a stereotypically feminine woman looking for protection from her partner; however, these stereotypes are tipped on their head by Barrett’s image, as the viewer instead sees a male in this vulnerable position. The technicalities of the image also serve to add to the overall gentle feel of the photograph, with the monotone colouring of the image presenting enough contrast to make out the different shapes and textures within the image, while still remaining soft enough for these shapes and edges to blend into, rather than harshly contrast, one another, therefore adding to the overall delicate and gentle atmosphere of the image. Barrett has successfully presented a response to the controversial concept of vulnerable masculinity, and her belief that “photography has always had the incredible power to challenge and redefine societal norms…” (Barrett, 2019 (3)) has allowed her to present this topic in such a way as to spark conversation between viewers about the harmful consequences of toxic masculinity on society.

Conclusion:

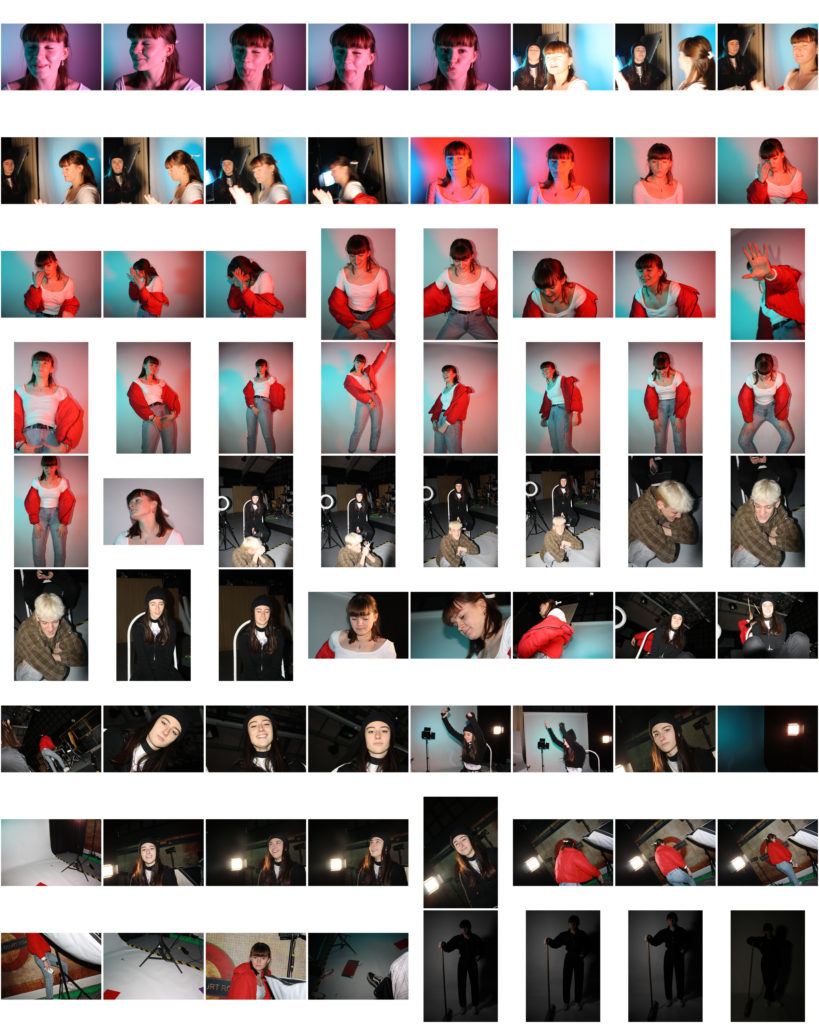

When it comes to the way both Sherman and Barrett present their work, they appear to take very different visual routes, while still sharing the overarching concept that gender should not be the defining aspect of an individual, and the strict rules and stereotypes held by society is damaging not only for the people they are targeted at, but for everyone. Barrett’s gentle approach to the idea of vulnerable masculinity presents the idea that men experience emotion and vulnerability just as much as women, and yet seeing men in vulnerable situations elicits a different response from the viewer, because of how out of the ordinary and contrast to normality it is. In the same way, Sherman touches on presenting an exaggerated idea of a female character, meant to reflect the outrageous standards placed on women in the media, eliciting a shocked response from the viewer. A more subtle similarity between Barrett and Sherman is their shared respect for self-portraiture as a means of self-reflection and representation of identity. Sherman’s work as a whole is heavily focused on self-portraiture, as it allows her to explore the identity of herself while creating and presenting a character, while for Barrett,”self-portraiture was a way of examining and almost verifying my own existence, I guess as a form of self-analysis and self-reflection”. (Barrett, 2019 (4)). In my own work, I have also made attempts to follow both the obvious and subtle approach to showing and braking strict gender roles. I have focused on showing stark contrast between reality and the gender stereotypes that people develop due to society’s influence, and to do this I have focused on presenting male subjects in feminine situations and environments (highlighting the contrast between the reality of gender expression, and the prejudice held by the viewer), and presenting female subjects in situations which reflect their dislike of adhering to strict feminine gender stereotypes and social norms. When it comes to my work with male subjects, I take inspiration from Cindy Sherman, and her method of presenting bold, intrusive work which draws the full attention of the viewer, and demands that they confront their own personal prejudice towards the image, while I also take inspiration from Phoebe Jane Barrett when it comes to my use of female subjects, using more subtle references to rebel against the right restraints of feminine gender stereotypes and roles.

Bibliography:

Bright, S. and Van Erp, H. (2019), Photography Decoded. London: Octopus Publishing House

Cumming, L (2019) Cindy Sherman, a Lifetime of making herself up, The Guardian, viewed 16 January 2020, < https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/jun/30/cindy-sherman-national-portrait-gallery-review-a-lifetime-of-making-herself-up>

Marili (2019) Soft, Intimate and Emotive: Redefining Masculinity with Photographer Phoebe Jane Barrett, EyeEm, viewed 17 December 2020 < https://www.eyeem.com/blog/redefining-masculinity-with-photographer-phoebe-jane-barrett-2018>

Hufkens, X, Adam Fuss, Xavier Hufkens, viewed 16 January 2020, < https://www.xavierhufkens.com/artists/adam-fuss>

Collins, G (1990) A Portraitists Romp Through Art History, The New York Times, viewed 16 January 2020, < https://www.nytimes.com/1990/02/01/arts/a-portraitist-s-romp-through-art-history.html>

Mulvey, L (1989) Visual and Other Pleasures, Palgrave Macmillan, UK

Stoffel, A. 204 Cindy Sherman, Phillips, viewed 1 January 2020, < https://www.phillips.com/detail/CINDY-SHERMAN/NY010413/204>

Adams, T (2016) Cindy Sherman: ‘Why am I in these photos?’, The Guardian, viewed 12 December 2019, < https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/jul/03/cindy-sherman-interview-retrospective-motivation>

Ginn, D (2019) Phoebe Jane Barrett Creates Tender Moments with Her Portrait Photography, The Phoblographer, viewed 21 January 2020, <https://www.thephoblographer.com/2019/07/12/phoebe-jane-barrett-creates-tender-moments-in-her-portrait-photography/>

Blessing, J (Winter 2017) “Rose is a Rose revisit”, Aperture (229) (98-103)

Bright, S (2010) AutoFocus the self-portrait in contemporary photography, London: Thames and Hudson