From kitschy to grotesque, this series ‘Common Sense’ documents modern consumerist culture. These vivid and often lurid photographs are both funny and sad, taking a forensic look at everyday items. A smorgasbord of over-the-top visuals, highlighting everything from tacky clothes and jewelry to different kinds of junk food.

Common Sense is a portfolio of 350 colour laser copies of photographs taken by Parr between 1995 and 1999. The portfolio was produced in an edition of ten; Tate’s copy is number nine in the series. The pictures were taken in the UK and abroad and depict images of global consumerism in tight close-up and lurid colour. They are designed to be displayed in a horizontal grid of at least three images by four. The artist has specified that it is not necessary to display all the photographs in the series when the work is shown. The selection of images can be arbitrary.

Common Sense was first shown in 1999 as an exhibition staged simultaneously in forty-one venues in seventeen countries. This earned Parr a Guinness World Record. To coincide with the exhibitions Parr produced a book, also called Common Sense, in which 158 images from the series were reproduced.

The photographs were taken with 35mm ultra saturated film which produces vivid, heightened colours. The pictures depict the minutiae of consumer culture, fragments that show the ways in which ordinary people entertain themselves. There are details of garish clothing and accessories, women’s faces heavy with make-up, and piles of merchandise in tourist shops, cake shops, sex shops and car boot sales. Fast food is a recurring theme: a child’s grubby hands clutching an over sized donut, rows of lollipops, plates overflowing with fried breakfasts and bowls piled high with ice cream. An overweight woman grips a hundred-dollar bill between her teeth. The images capture the feel of disposable culture in the developed world.

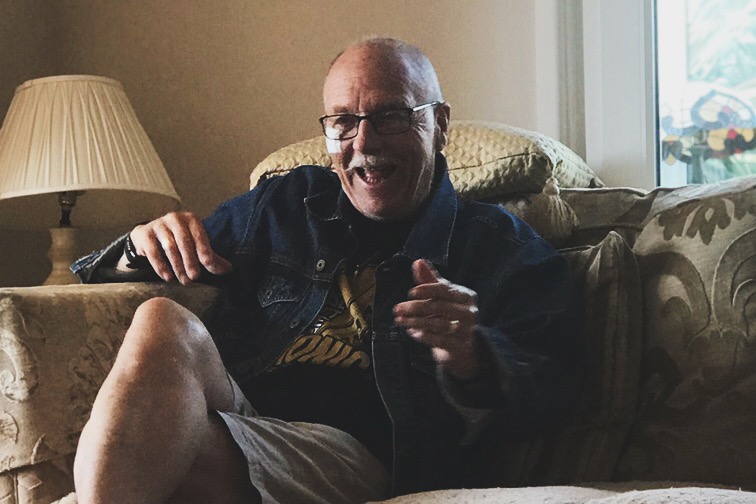

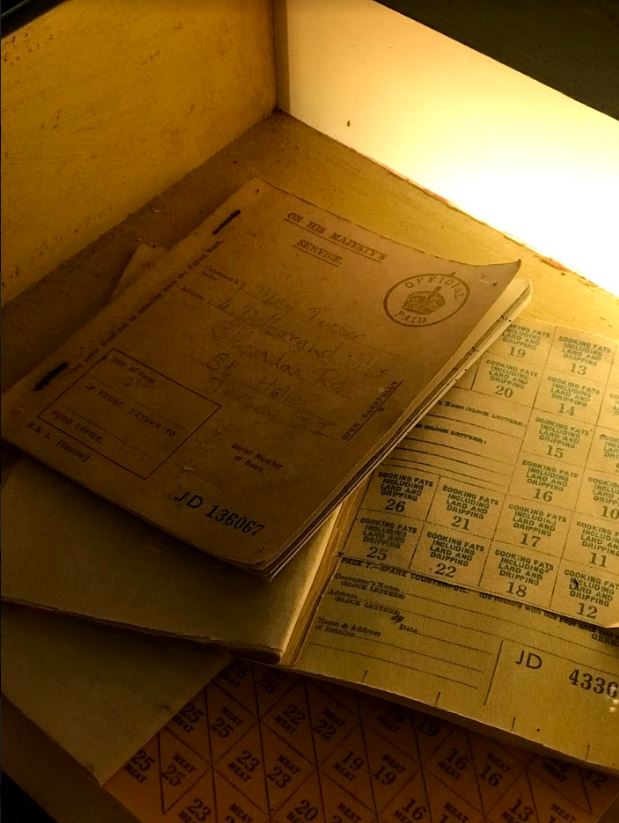

Parr’s pictures both reinforce national stereotypes and demonstrate how consumer culture has made international boundaries more indistinguishable. Because the images are tightly cropped, in many cases it is impossible to discern where they were taken: a balding head beneath a purple baseball cap and immaculately manicured false nails would once have appeared typically middle American but are now prevalent in other parts of the world. In other instances, small details immediately situate the image: a cup of milky tea on a red checked tablecloth is ironically British.

The proliferation of images in the series is simultaneously exuberant and repulsive. The excess Parr depicts is mimicked in the accumulation of details he presents. His hypersaturated colour contributes to optical overload. The images hover between hedonistic celebration and a cloying sense of disgust for what may be seen as the more debased aspects of contemporary culture. Parr’s vivid eye for comic and often cruel juxtapositions of images is evident in his choice of paired images in his book: a sunburned body next to raw meat on butchers’ hooks; a poster advertising chips next to a crawling mass of maggots. Pictures of discarded food and rubbish pecked at by pigeons can be read as contemporary memento mori images. Occasionally, Parr’s emphasis on overconsumption (a Spice Girls t-shirt stretched taut across a fat midriff, teeth flecked with scarlet lipstick) is tempered by images which suggest a gentler, slower-paced culture on the wane: a pensioner in a cloth cap, a pair of feet in socks and sandals.

The work’s title plays on the double meaning of common as vulgar. Parr began his career as a photojournalist and the images in Common Sense are examples of the candid, detached approach typical of observational photography. His dissections of contemporary mores can also be seen in the tradition of English satirists dating back to William Hogarth (1697-1764).