4. Contemporary practice: Complete at least one artist reference on how contemporary photographers explore still life and objects in their work. What meaning can we attribute to images of food and everyday objects – consider social, economical and cultural references.

Walker Evans, (born November 3, 1903, St. Louis, Missouri , U.S.—died April 10, 1975, new haven, Connecticut), American photographer whose influence on the evolution of ambitious photography during the second half of the 20th century was perhaps greater than that of any other figure. He rejected the prevailing highly aestheticized view of artistic photography, of which Alfred Stieglitz was the most visible proponent, and constructed instead an artistic strategy based on the poetic resonance of common but exemplary facts, clearly described. His most characteristic pictures show quotidian American life during the second quarter of the century, especially through the description of its vernacular architecture , its outdoor advertising, the beginnings of its automobile culture , and its domestic interiors.

Most of Evans’ early photographs reveal the influence of European modernism, specifically its formalism and emphasis on dynamic graphic structures. But he gradually moved away from this highly aestheticized style to develop his own evocative but more reticent notions of realism, of the spectator’s role, and of the poetic resonance of ordinary subjects. The Depression years of 1935–36 were ones of remarkable productivity and accomplishment for Evans. In June 1935, he accepted a job from the U.S. Department of the Interior to photograph a government-built resettlement community of unemployed coal miners in West Virginia. He quickly parlayed this temporary employment into a full-time position as an “information specialist” in the Resettlement (later Farm Security) Administration, a New Deal agency in the Department of Agriculture.

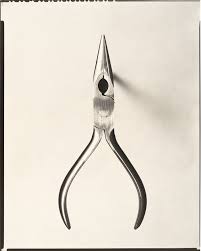

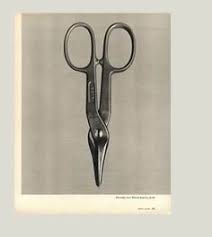

Between 1934 and 1965, Evans contributed more than 400 photographs to 45 articles published in Fortune magazine. He worked at the luxe magazine as Special Photographic Editor from 1945 to 1965 and not only conceived of the portfolios, executed the photographs, and designed the page layouts, but also wrote the accompanying texts. His topics were executed with both black-and-white and color materials and included railroad company insignias, common tools, old summer resort hotels, and views of America from the train window. Using the standard journalistic picture-story format, Evans combined his interest in words and pictures and created a multidisciplinary narrative of unusually high quality. Classics of a neglected genre, these self-assigned essays were Evans métier for twenty years.

In 1973, Evans began to work with the innovative Polaroid SX-70 camera and an unlimited supply of film from its manufacturer. The virtues of the camera fit perfectly with his search for a concise yet poetic vision of the world: its instant prints were, for the infirm seventy-year-old photographer, what scissors and cut paper were for the aging Matisse. The unique SX-70 prints are the artist’s last photographs, the culmination of half a century of work in photography. With the new camera, Evans returned to several of his enduring themes—among the most important of which are signs, posters, and their ultimate reduction, the letter forms themselves.